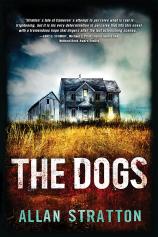

In Allan Stratton’s

THE DOGS, Cameron --- a boy who rents a creepy farmhouse in Wolf Hollow with his mom --- can’t tell what’s real and what is in his head. But he has to overcome a lot more than an overactive imagination. Since memory and perception play such a big role in this eerie new thriller, we asked Allan to tell us about the ways that the mind alters reality to deal with trauma, both in his book and in his own life.

You’re right, Cameron does have a lot more on his mind than an overactive imagination. He and his mom have been on the run for several years from his father, whom his mother claims is a psychopath out to kill them. They change locations every time she says his dad has stalked them down. If she’s right, they’re in danger of being murdered. But if she’s delusional, Cameron’s in another kind of danger.

Even worse: Cameron begins hearing and seeing the ghost of a boy, Jacky; he believes Jacky’s father murdered him on the farm 50 years ago. Cameron and the reader are wrenched between two frightening possibilities. One, that Cameron is endangering himself by trying to track down the facts behind a cold-case murder. Two, that the real danger is Cameron’s fear of his own father, which is driving him to self-destruction and madness.

My own situation was never as severe as Cameron’s, but it’s where Cameron’s life took root. When I was a baby, my mother fled with me to my grandparents’ farm and then to a nearby town very much like Cameron’s Wolf Hollow. I grew up wondering: Is my father the man my mother loved enough to marry, or is he the one who has her in fear for her life? If I can’t know the truth about my own father, how can I know the truth about anyone?

We also commonly misinterpret everyday events. A friend snaps at us and we wonder what we did. Quite often, nothing: they may have snapped because of something that doesn’t even involve us. This happens with Cameron and his mother, and, more dangerously, with his enemy Cody. Physical or mental infirmities multiply the problem. I remember my grandfather suddenly weeping at the piano bench: “I saw the keys rise up in a wave,” he said. “I know that can’t have happened, but it’s what I saw.”

If, like Cameron, we can’t trust our knowledge of family and friends or our interpretation of events, we can trust our memories even less. A personal example:

When I was a child, my father had to wait for me in his car on visit days; my mother was too afraid to let him near the house. One night, he followed me back to the doorstep. He wanted me to stay with him overnight in the town hotel. Mom said he had ‘that look.' They played tug of war with me as the rope. Mom let go and he took off with me. She called the cops. He returned me a few hours later.

In my memory, the story ends with Mom and me going out and buying a Christmas tree. But I’m wrong. It happened in late spring. So what really happened in the hours before Dad brought me home? Did I make up a happy ending to protect myself from remembering something terrible? Or did my mind simply create a random mash-up of two real but separate events? I’ll never know.

What I do know is that whenever people are asked to remember the same traumatic event, they each remember it differently. And, as they repeat the story, the details change. That’s one of the reasons so many innocent people are convicted of crimes. (Aside from being buried alive, my biggest fear as a kid was that I’d be executed for a murder I didn’t commit.)

I also know that everyone has secrets. Mr. Sinclair, who lives on the farm next to Cameron, would have been Jacky’s age when he was a boy. They’d have known each other. Does Mr. Sinclair have secrets about Jacky’s disappearance? What happens when people pry at other people’s secrets?

Each of us struggles to know and understand who we are. We try to piece together our memories and histories, our families and friends, in a way that gives our lives meaning and purpose. But how can we do that when we don’t know the secrets of those closest to us, and when we can’t trust the truth of what’s in our own heads?

I think that’s one of the reasons we turn to fiction. As writers and readers, we live through imagined worlds to help us come to terms with the greatest unknowable: ourselves.

Allan Stratton is the internationally acclaimed author of CHANDA'S SECRETS, winner of the American Library Association's Michael L. Printz Honor Book, the Children's Africana Book Award, and ALA Booklist's Editor's Choice among others. His first YA novel was the ALA Best Book LESLIE'S JOURNAL. His novel CHANDA'S WARS, a Junior Library Guild selection, won the Canadian Library Association's Young Adult Canadian Book Award, 2009, and is on the CCBC Best Books List.

Allan Stratton is the internationally acclaimed author of CHANDA'S SECRETS, winner of the American Library Association's Michael L. Printz Honor Book, the Children's Africana Book Award, and ALA Booklist's Editor's Choice among others. His first YA novel was the ALA Best Book LESLIE'S JOURNAL. His novel CHANDA'S WARS, a Junior Library Guild selection, won the Canadian Library Association's Young Adult Canadian Book Award, 2009, and is on the CCBC Best Books List.

Allan Stratton is the internationally acclaimed author of CHANDA'S SECRETS, winner of the American Library Association's Michael L. Printz Honor Book, the Children's Africana Book Award, and ALA Booklist's Editor's Choice among others. His first YA novel was the ALA Best Book LESLIE'S JOURNAL. His novel CHANDA'S WARS, a Junior Library Guild selection, won the Canadian Library Association's Young Adult Canadian Book Award, 2009, and is on the CCBC Best Books List.  Allan Stratton is the internationally acclaimed author of CHANDA'S SECRETS, winner of the American Library Association's Michael L. Printz Honor Book, the Children's Africana Book Award, and ALA Booklist's Editor's Choice among others. His first YA novel was the ALA Best Book LESLIE'S JOURNAL. His novel CHANDA'S WARS, a Junior Library Guild selection, won the Canadian Library Association's Young Adult Canadian Book Award, 2009, and is on the CCBC Best Books List.

Allan Stratton is the internationally acclaimed author of CHANDA'S SECRETS, winner of the American Library Association's Michael L. Printz Honor Book, the Children's Africana Book Award, and ALA Booklist's Editor's Choice among others. His first YA novel was the ALA Best Book LESLIE'S JOURNAL. His novel CHANDA'S WARS, a Junior Library Guild selection, won the Canadian Library Association's Young Adult Canadian Book Award, 2009, and is on the CCBC Best Books List.