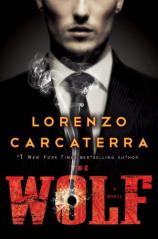

Kicking off this year's Father’s Day Blog series is Lorenzo Carcaterra, a former journalist and the #1 New York Times bestselling author of SLEEPERS, GANGSTER and MIDNIGHT ANGELS. In his latest novel, THE WOLF (out July 29th), organized crime goes to war with international terrorism in the name of one man’s quest for revenge. Carcaterra’s fascination with true crime --- organized and otherwise --- started early, when he and his father indulged in their “ritual of the papers” after a long day of work. His dad preferred tabloid and boxing stories, but Carcaterra couldn’t resist exploring the rest of the newspaper. His dream, he admitted when pressed, was to write stories. A serendipitous appearance by Truman Capote on “The Merv Griffin Show” and his father’s understated, unwavering encouragement inspired Carcaterra to achieve just that.

Kicking off this year's Father’s Day Blog series is Lorenzo Carcaterra, a former journalist and the #1 New York Times bestselling author of SLEEPERS, GANGSTER and MIDNIGHT ANGELS. In his latest novel, THE WOLF (out July 29th), organized crime goes to war with international terrorism in the name of one man’s quest for revenge. Carcaterra’s fascination with true crime --- organized and otherwise --- started early, when he and his father indulged in their “ritual of the papers” after a long day of work. His dad preferred tabloid and boxing stories, but Carcaterra couldn’t resist exploring the rest of the newspaper. His dream, he admitted when pressed, was to write stories. A serendipitous appearance by Truman Capote on “The Merv Griffin Show” and his father’s understated, unwavering encouragement inspired Carcaterra to achieve just that.

My father was barely literate, and my mother didn’t speak English. Nor did I until I started grade school. And there were no books in the railroad apartment we shared in Hell’s Kitchen other than my collection of Classics Illustrated comics that I kept in a neat pile in a hall bureau. My dad worked as a butcher at the old 14th Street meat market, now known more for its high-end clothing stores and restaurants than for trucks packed with hind quarters bound for uptown destinations.

My dad’s workday began at three in the morning and ended just about the time school let out. I would wait for him on the stoop of our building, catching him coming off 10th Avenue, his white butcher’s smock smattered with blood, a packet of fresh cut beef under one arm, the other holding a thick stack of the day’s newspapers and one, sometimes two boxing magazines. Soon as he was close enough, he tossed the packet of beef to me, and we made our way up to our second floor apartment. My dad would shower, have his dinner and then come into our sparsely furnished living room, the stack of papers and magazines resting by my side. He was tired from a long day lugging 200-pound hindquarters off of trucks and would lie down and wait for me to reach for one of the papers and read aloud to him.

This was our time together, and we had a routine. In those days, the mid-to-late-1960s, there were many newspapers in New York City, and my father brought them all home, except for the New York Times. I never asked him why, but I assumed he preferred tabloids to broadsheets. We started with sports, which meant reading from back to front (a habit I have kept up to this day), and from there we moved to crime. He loved boxing stories the most, which explains why I know more about Henry Armstrong and Beau Jack than I do about Proust.

My dad was a boxer when he was young and a pretty good one from what the old-timers who saw him fight told me. He would go out of state to fight in winner-take-all “whiskey bouts.” You go into one fight as Mario Jones and win, come back for another as Mario Smith and win again. Some nights my dad fought and won as many as five fights.

Now, reading five or six sport and crime sections covering the same stories can get a bit tedious, so I started exploring other parts of the papers. I began reading columnists to my dad, and no one struck home with the two of us more than did the work of Pete Hamill. I was struck by his passion, his anger, his way with words, and the rhythm with which he would begin and end each column. In no time at all, I fell in love with newspapers --- and maybe even with writing --- just by hearing his written words.

My father liked Jimmy Breslin’s columns, too, especially when he wrote about wise guys and Dick Young’s take on baseball and the wonderful Bill Gallo illustrations. We would take an occasional break, talk about his favorite players (Harmon Killebrew and Jim “Mudcat” Grant of the Minnesota Twins) and gangsters (Owney Madden topped that list) and movies (anything with James Cagney, but none better than Angels With Dirty Faces where he played Rocky Sullivan, a character modeled after “Two-Gun” Crawley, who was in a massive police shootout on the Upper West Side in the 1930s).

I was in the middle of a story about a robbery gone wrong in the Village when my father interrupted.

“You think about it yet?” he asked.

“Think about what?”

“What you’re going to do,” he said. “With your life, I’m talkin’ about.”

I hesitated before I answered. I had given a lot of thought to it, but didn’t see how I could make it happen. I wanted to write stories, work on a newspaper, but knew it was nothing more than a pipe dream. We didn’t know anyone who even knew someone who worked close to a newspaper. “I want to write stories,” I finally blurted out.

My father stared at me for a few seconds. “What kind of stories?”

“I don’t know yet,” I said, anxious to get back to the reading.

He shrugged. “Well you better figure that out,” he said.

After the ritual of the papers, my mother would join us in the living room and turn on the small black-and-white television that rested in one corner. Now, I could understand why my parents liked certain shows --- my dad loved “The Untouchables” and “M Squad” for the obvious reasons. My mother sat glued to “Combat” because she had lost so much in Italy during World War II and watched anything that featured Perry Como (as did every other Italian woman in the neighborhood). But for reasons that escape me to this day, both my parents loved watching “The Merv Griffin Show,” a nightly talk show that aired on what was then called “channel five.” I found it odd since my mother spoke no English, and my father was clueless as to who any of the celebrity guests were. Occasionally, I would sit and watch with them, looking from one to the other and wondering what enjoyment they could possibly be getting from the show.

Then one night, a guest came on who caught the attention of both my dad and me. It was Truman Capote. I had never seen him before and found him to be entertaining and a great storyteller. I glanced over at my father. “He’s a writer this guy,” my father said. “Tells stories. Just like you want to do.”

I nodded. “Books, I think,” I said. “Maybe I’ll check him out at the library tomorrow.”

“Do that,” my father said. “Curious to see what kind of stories he likes to tell.”

The next afternoon, I checked out Truman Capote at the library on 10th Avenue. There were two books under his name: BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S and IN COLD BLOOD. I took a shot with the second one.

My father held the book and glanced at the title. “Sure it’s the same guy that was on Merv?”

“Yeah,” I said. “His name’s right there.”

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s hear it.”

For the next three weeks, in between sports sections and crime stories, I read a few pages of IN COLD BLOOD aloud each day to my dad. He never said a word one way or the other whether he liked it or not, and I never asked. Then, one night, the apartment stifling hot from a late spring heat wave, my dad stopped me in mid-sentence.

“This writing thing, telling stories,” he said, “you still got your mind set on that?”

“I think so,” I said. “Not sure how, but I’d like to give it a try.”

“All right, then,” he said. “You’ll get no argument from me. Give it your best shot. Like this guy, what’s his name, Capone?”

“Capote,” I said.

My dad nodded. “Go for it,” he said. “And don’t let anybody tell you otherwise. I’m with you all the way.”

“Thanks, dad,” I said.

And thanks Mr. Capote.