Anita Amirrezvani was born in Tehran, Iran, and raised in San Francisco. For ten years, she was a dance critic for newspapers in the Bay Area. She has received fellowships from the National Arts Journalism Program, the NEA's Arts Journalism Institute for Dance, and the Hedgebrook Foundation for Women Writers. Amirrezvani is a student in the MFA program in fiction at San Francisco State University. Here, she talks about her father's love of poetry.

Anita Amirrezvani was born in Tehran, Iran, and raised in San Francisco. For ten years, she was a dance critic for newspapers in the Bay Area. She has received fellowships from the National Arts Journalism Program, the NEA's Arts Journalism Institute for Dance, and the Hedgebrook Foundation for Women Writers. Amirrezvani is a student in the MFA program in fiction at San Francisco State University. Here, she talks about her father's love of poetry.

My dad, a retired civil engineer and businessman, has always had a deep love of Iranian poetry. When I was growing up, he and his friends used to play a poetry game called mosha' ereh.

Usually we’d be sitting around at home eating or drinking, and someone would suggest the game. One person would begin by reciting a poem in Farsi. Whatever letter ended the poem --- say, an “a,” would provide the challenge for the next person, who would have to think of a poem whose first letter began with an “a”. The final letter of that poem would provide the next challenge.

At my dad’s house, players would listen intently for the final letter and then jump in as fast as they could with their poem. The main pleasure of the game came from listening to the poetry, but the ultimate goal was to recite a poem that stumped everyone else. When no one could think of another poem that fit the requirements, the person who had recited the last poem became the winner.

My dad has always excelled at the game. Although I often didn’t understand the poems, I admired his grace in remembering and delivering the lines. Most of the poems were either in rhyming couplets or had another rhyming scheme that aided memorization. My father would declaim the poems in a deep, percussive voice that emphasized their internal rhymes as well as their final ones. If he hit the mark with a much-loved poem, his audience would say, “Bah, bah!” in appreciation.

I called him recently and asked, “Baba, how did you get so good at the game?”

“I’m not that good at it,” he replied, as modest as ever. But then he went on to explain that he had had to recite poetry as a schoolchild in Tehran, and his elders often called on him to perform poems at family gatherings.

Such reverence for poetry is typical among Iranians. Even today it’s common for Iranians to throw a rhyming couplet into conversation to make a pithy point. The other day I heard a caller on a Farsi-language news program recite a couplet by the great poet Ferdowsi, but I didn’t get the whole thing. I asked my father if he knew the verse. He didn’t, but he responded with another famous one:

Miazar moori ke daneh kesh ast ke jaan dared-o jann shireen khosh ast

(Don’t hurt the ant, carrier of little things For it is alive, and its life is sweet.)

The lines were written by Ferdowsi more than one thousand years ago. They’re from his Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, which consists of sixty thousand lines about the legendary and historic kings of Iran. The book also explores the art of leadership in all its forms. My father has read the entire book twice and consulted parts of it throughout his life. In some ways, it is a manual for living.

When I was working on my novel EQUAL OF THE SUN, I read the SHAHNAMEH in a translation by the scholar Dick Davis, and I cited a few passages from his translation in my book. It seemed to me likely that at times of great feeling, my sixteenth-century characters, who were educated and urbane, would feel the urge to express themselves by reciting or writing poetry.

Before long, I realized that I was going to need to make up some poems to convey their feelings. I’m not a poet, but there was no getting around it. To get into the rhythm of creating these poems, I conjured up the sound of my father’s voice when he played mosha' ereh. I thought of how the rhymes snapped together as tightly as puzzle pieces and of the deep satisfaction on his listeners’ faces after he recited a meaningful poem.

When my father was reading EQUAL OF THE SUN, I asked him what he thought about my poems. “Not bad,” he replied with a smile. He’s a man of few words, and I considered that to be high praise from a poetry lover like him. I’ll never be a Ferdowsi, but if I can give my readers a sense of the passion that my Iranian characters feel about the art of poetry, I’ll be satisfied.

For Father’s Day, here are a few lines of appreciation for my dad in the spirit of old Iranian poetry:

Out poured verse when you were fresh like morning dew

Your rose-like face bloomed with the poems inside of you

Your rich, nectared voice astonished even the honeybee

Thank you, Baba-joon, for the fertile words you gave to me.

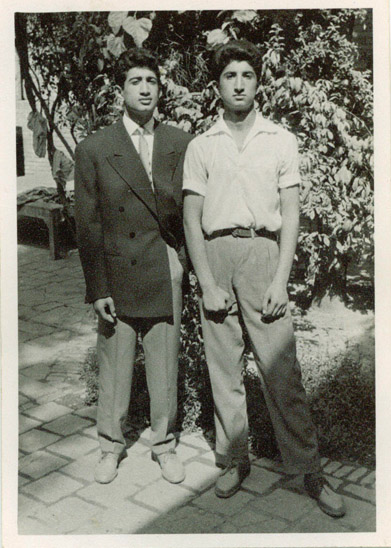

Pictured below is Anita's Father, Ahmad, at age 16, with her uncle Mahmood, age 14

Anita Amirrezvani was born in Tehran, Iran, and raised in San Francisco. For ten years, she was a dance critic for newspapers in the Bay Area. She has received fellowships from the National Arts Journalism Program, the NEA's Arts Journalism Institute for Dance, and the Hedgebrook Foundation for Women Writers. Amirrezvani is a student in the MFA program in fiction at San Francisco State University. Here, she talks about her father's love of poetry.

Anita Amirrezvani was born in Tehran, Iran, and raised in San Francisco. For ten years, she was a dance critic for newspapers in the Bay Area. She has received fellowships from the National Arts Journalism Program, the NEA's Arts Journalism Institute for Dance, and the Hedgebrook Foundation for Women Writers. Amirrezvani is a student in the MFA program in fiction at San Francisco State University. Here, she talks about her father's love of poetry.