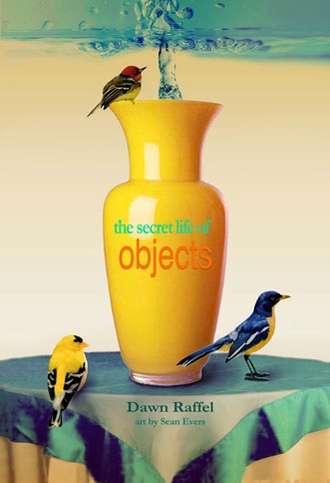

Dawn Raffel’s forthcoming memoir, The Secret Life of Objects, is a life story revealed through simple possessions --- a coffee mug, a vase, a pair of earrings, my mother's prayer book…things that hold a hidden memory. The book will be released in June but is available for pre-order at a pre-publication discount here: http://jadedibisproductions.com/SECRET.html. Her previous books are two story collections—Further Adventures in the Restless Universe and In the Year of Long Division—and a novel, Carrying the Body. She is the books editor at Reader’s Digest, and the editor of The Literarian, the online journal of the Center for Fiction in New York.

Dawn Raffel’s forthcoming memoir, The Secret Life of Objects, is a life story revealed through simple possessions --- a coffee mug, a vase, a pair of earrings, my mother's prayer book…things that hold a hidden memory. The book will be released in June but is available for pre-order at a pre-publication discount here: http://jadedibisproductions.com/SECRET.html. Her previous books are two story collections—Further Adventures in the Restless Universe and In the Year of Long Division—and a novel, Carrying the Body. She is the books editor at Reader’s Digest, and the editor of The Literarian, the online journal of the Center for Fiction in New York.

My mother and I were close during the 47 years we were alive together, but in some ways we were never more intimate than when I was faced with dismantling her home after her sudden death.

Just past her 78th birthday, my mother was not in perfect health, but there was nothing to indicate that she simply would not wake up one Tuesday morning. It was as if she had left the world mid-thought. Nothing had been dispensed with or sorted for removal, and after my stepfather’s death not long after, it fell to me to see to the house’s contents.

In any mother-daughter relationship, even when both parties are adults, there are things we don’t show each other, aspects of the self that we chose not to share. Every surface in my mother’s home was clean and tidy, but the insides of drawers and cabinets revealed a riot of feeling, of nostalgia, of loneliness, of delight. She had saved so much: favors, trinkets, notes from classes she had taken decades ago, every letter I had ever sent from camp (invariably asking for candy), armloads of mementoes from my sister’s and my childhood, clothes she hadn’t worn in 30 years, photographs not only of her parents and cousins but also of people I had no way to identify, but who must have meant something to her. My mother had been an artist, and while I had seen most of her paintings, there were sketches and older pieces dating back to her high school years that she had stowed and never taken out --- records of the woman she had been, precursors of the woman she became. Among the family papers was a manila folder labeled in angry black maker “divorce.” I held the folder in my hand, felt the pain of that rupture reverberate through time, beyond both of my parents’ deaths. I threw the folder in the trash.

But I took home a lot: her jewelry, her scarves, her pretty coffee cup, pages with her handwriting on them. Her clothes did not fit me but her shoes did, as if they had been made for me, or I for them. I often wear the vintage Ferragamos I found stored in the basement, nested in tissue; I think she had forgotten they were there. Her paintings and her paperweights inhabit my rooms. Her watch is on my wrist.

Taking apart my mother’s home was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, but I am grateful --- for what she saved, for what I learned, for being allowed to know her more deeply. My mother is very much with me.