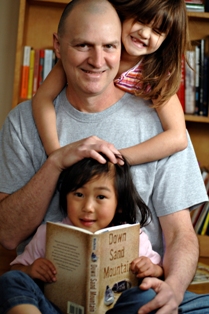

Steve’s fiction, poetry, and non-fiction articles have appeared in numerous publications, including The Nation, Poets & Writers, Mississippi Review, 100 Percent Pure Florida Fiction, North American Review and The Pushcart Prize Anthology. A graduate of Florida State University, Steve teaches journalism, creative writing, and Vietnam War literature at the University of Mary Washington. He also teaches Ashtanga yoga, and has worked as an investigator and advocate for abused and neglected children through the child advocacy organization CASA. Steve lives in Fredericksburg, Virginia with his wife Janet, and is the father of four daughters–Maggie, Eva, Claire, and Lili. Steve and Janet have served for the past three years as co-directors of the religious education program at the Fredericksburg Unitarian Universalist Church. Steve and Lili, who is 6, are active volunteers in Tree Fredericksburg, an urban reforestation project.

Steve’s fiction, poetry, and non-fiction articles have appeared in numerous publications, including The Nation, Poets & Writers, Mississippi Review, 100 Percent Pure Florida Fiction, North American Review and The Pushcart Prize Anthology. A graduate of Florida State University, Steve teaches journalism, creative writing, and Vietnam War literature at the University of Mary Washington. He also teaches Ashtanga yoga, and has worked as an investigator and advocate for abused and neglected children through the child advocacy organization CASA. Steve lives in Fredericksburg, Virginia with his wife Janet, and is the father of four daughters–Maggie, Eva, Claire, and Lili. Steve and Janet have served for the past three years as co-directors of the religious education program at the Fredericksburg Unitarian Universalist Church. Steve and Lili, who is 6, are active volunteers in Tree Fredericksburg, an urban reforestation project.

1. Your narrator/protagonist is (almost) always both precocious AND naïve---starting out as unreliable (though usually well-meaning), but ending up as reliable. That ironic gap between what your narrator thinks or says is going on and what your readers see or suspect is really happening is an important source of tension, pathos, and/or humor.

2. The voice of your narrator has to sound true to the chronological age of the protagonist, while at the same time generally more articulate---elevated in diction, syntax, and sophistication of thought. It’s a balancing act. If the voice is too young and too naïve, you infantilize your narrator and have credibility problems (and maybe a MG novel instead of YA). If the voice is too sophisticated, you have credibility problems as well. (A protagonist with specialized, adult-level knowledge tends to work better in MG than in YA. )

3. Remember that as a general rule, your market demographic is determined by the age of your protagonist, even if you have a fairly young protagonist but more mature themes. YA readers don’t want to read down. That is, 16 year olds don’t want to read about 12 year olds, though the reverse isn’t necessarily true. My book DOWN SAND MOUNTAIN is a case in point --- 12-year-old narrator, mature themes, but still marketed for younger readers when perhaps better suited to older YAs and adults.

4. Give your characters resonant names. In DOWN SAND MOUNTAIN I have a naïve, 12-year-old protagonist named Dewey, a little sister named Tink, a drunk doctor named Rexroat, a clueless police officer named O. O. Odom, a best friend named Boopie, a Vietnam vet named Walter Wratchford. All names have resonance, of course, but some have greater thematic resonant than others.

5. And sometimes you just want a good old-fashioned Everyman or Everywoman character. His name is Charlie. Her name is Annie.

6. Don’t isolate your protagonists. We need to see them engaged with other characters. That’s principally how you’ll move your plot forward, develop your central characters, and explore your themes. If you find your protagonist all alone, sitting and thinking, ruminating, remembering, then you’ve probably found a scene you should rewrite. With other characters in it, too.

7. Don’t introduce too many characters at once. You’re probably already lost trying to remember all the characters I just introduced in that name explosion above in #4. Remember the Rule of Three: That’s the number for the most individual characters you generally want to introduce in any given scene.

8. Don’t give your characters names that are too similar. Cathy and Angie and Allie are all the same girl. Billy and John and Dan are the same boy.

9. Describe your crowds first --- think about that establishing shot in films --- THEN zoom in on someone in the crowd. Let us get to know that character before you introduce any others. Remember the Rule of Three (see #7 above).

10. The idea of characters being either Flat or Round can be helpful. Some are barely present; others are central to your story. But ALL your characters should matter. When your flat characters are real --- even those making the tiniest cameos --- they help breathe life into your Round characters, and add greater spice to your story. To put it another way, if your protagonist interacts with undeveloped characters or stereotypes, you lose tension and authenticity because we already know what our reaction to those characters should be (boos and hisses for the bad guys, tears for the innocent), and we likely know the outcome of the interaction before we even read it.

11. Love your villains. Create characters that your readers want to spend time with --- even if it’s to hate them, despise them, condemn them, and see them get their just desserts. The Joker is much more interesting than Batman in The Dark Knight. Satan gets all the best lines in PARADISE LOST.

12. In part this is also because heroes are boring if they’re too good. Reluctant heroes, with flaws, foibles, feet of clay---that’s who we want to spend our time with. Think Jo in LITTLE WOMEN. Angelic Beth: not so much. (For more on Beth, see “10 Things to Remember About Death in YA Fiction,” below.)

13. On a related note: consistency is definitely important in your characters, and in your narrator and his or her voice. But too much consistency kills tension and leads to boredom and is bad for sales. What you want is complexity. Let your characters surprise you sometimes. Let them surprise other characters. Let them surprise your readers.

14. You have an enormous arsenal of weapons at your disposal --- I suppose we should go with the gentler term, narrative techniques --- for developing your characters. Here they are, though obviously some only apply to your protagonist, as we don’t generally have access to the thoughts, memories, etc. of most of your other characters:

What the character looks like.

What the character says.

What the character does.

What the character thinks and feels.

What the character remembers.

What the character has done in the past.

What the character imagines, wants, needs.

How the character acts in relationships with others.

What the character DOESN’T say or do or think.

What others think or say about another character.

But keep in mind that ALL of this is or should be filtered through the observing consciousness --- that is, the observations, thoughts, memories, experiences of your protagonist --- so frequently can end up telling us as much about the protagonist as it does about the other characters being described. And, fortunately, sometimes your protagonist gets to be wrong.

And on a final note, now that you’ve brought these characters to life, sometimes you have to kill a few off. Which brings us to:

10 THINGS TO REMEMBER

ABOUT DEATH IN YA FICTION

1. There’s no life without death

2. Kill early, not often

3. The only good surprise is an inevitable surprise. Foreshadow your late deaths.

4. If you have to kill late, don’t do it in the last chapter

5. Killing off bad guys isn’t killing --- it’s poetic justice

6. Most deaths are better heard than seen

7. If you kill a dog, replace it with a puppy

8. The dead have warts too, you know

9. Cute grief is no grief at all

10. The dead are never really dead