My first experience with the phenomenon of book banning --- which features in a subplot of my new novel,

I WILL RUIN YOU --- occurred when I was in the fifth grade.

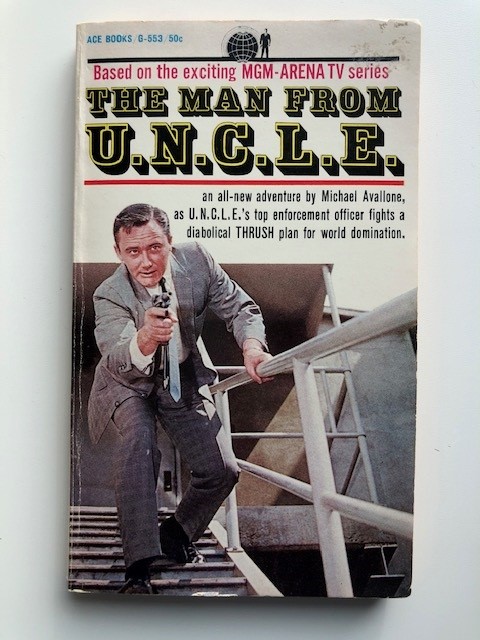

The book was THE THOUSAND COFFINS AFFAIR by Michael Avallone, and it was the first in series of novels based on the TV show “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.”

The book banner was my mother.

I was 10 years old and obsessed with the spy adventure series. So when a book based on the show hit the paperback racks (50 cents!), I snatched it up. (Avallone, by the way, was one of the most prolific authors at the time of TV novelizations and other crime novels.) I was already a devoted reader of The Hardy Boys mysteries and Tom Swift’s escapades about his fantastical inventions, but this U.N.C.L.E. thriller felt like a step up, something a little more mature.

Mom must have seen it that way, too. She started thumbing through the pages, came upon a reference to a naked woman, and had a case of the vapors. And just like that, the book was withdrawn from household circulation, buried under other items on the top shelf of our front hall closet.

I was not deterred. Whenever she was out, I would grab a chair, climb atop it, get the book down from the shelf and read a chapter or two. Then, before she got home, I’d put it back in its hiding place, should she decide to check and see if it was still there.

My next experience with book banning came years later, in my 20s, when I was a reporter for the

Peterborough Examiner in Ontario. I came up against a campaign to ban from the curriculum of a high school in nearby Lakefield a novel called THE DIVINERS by Margaret Laurence. Laurence was not only one of Canada’s most celebrated literary writers of the time. She was a good friend and hugely supportive of my dream of becoming a crime novelist one day. (I used to keep her well supplied with Rex Stout and Ross Macdonald novels.) Laurence lived in Lakefield, and this campaign, led by a minister from a local Pentecostal church, was not only maddeningly closed-minded, but also deeply hurtful.

THE DIVINERS was the rich, profoundly beautiful, raw and honest story of Morag Gunn, a writer struggling with her own daughter’s independence, haunted by her past, struggling to come to terms with her future. (It was adapted into a movie here in Canada years later.)

That minister just thought it was dirty. He branded Laurence a pornographer, which was a pretty good clue this guy had never seen inside the pages of Penthouse. At one point, I interviewed another minister with a similar outlook. To prove his point that the book was pure filth, he directed me to a passage where Morag watches, with some fascination, two flies copulating.

Now, if that’s the kind of thing you believe is going to get young readers’ motors running, I respectfully suggest you need to talk to someone.

My wife, Neetha, and I spent a lot of time with Laurence during this period and saw the toll it took on her. How her thoughtful work could be so categorized was beyond baffling to us. But years later, as we see new attempts to ban books, demonize librarians, and supposedly protect children from works of literature that celebrate acceptance, condemn racism and tackle coming of age with directness, we see how little has changed.

There is a segment of society that will always be fearful of letting children think for themselves, of confronting ideas that may challenge them.

In my novel, a teacher runs into trouble when he introduces his students to a novel not on the curriculum. The book is THE ROAD by Cormac McCarthy, and one of the teacher’s students is troubled --- but far from traumatized --- by a depiction in the novel of cannibalism. This ends up, as they say, biting our teacher in the butt. One parent questions why the school would force students to read a book that celebrates people devouring one another.

It’s pretty clear to anyone who has read THE ROAD that celebration was not McCarthy’s intention.

Here’s part of what my teacher character, Richard, tells parents at a hastily called meeting:

“Most novels, most good novels, involve conflict and what human beings do to resolve it. THE ROAD is a story about survival in the wake of a global catastrophe, and for kids who have grown up on stuff like ‘The Walking Dead’ and 28 Days Later, it’s a way to engage them, to get them past the gore and the sensationalism and guide them toward a discussion of complicated moral issues…. I would be doing your children a disservice if I made every effort to protect them from things that might challenge or upset them. I could cocoon them, avoid anything that might spark debate, that would raise questions of right and wrong. Of course, that would mean not reading any great works of fiction at all, because that’s what we hope good fiction will do. Get the kids talking, thinking. Good fiction provokes and bridges gaps, can bring people together by exposing them to all sides of an issue.”

Richard knows he’d be a fool to think this will be enough to win over his opponents. But that doesn’t mean that he --- and all of us who believe in freedom of thought and expression, who oppose the suppression of ideas --- will stop trying.

A small postscript: I now have two copies of THE THOUSAND COFFINS AFFAIR and a framed blowup of the cover on my wall signed by one of the stars of the TV series. Kids always find a way, even if it takes a few decades.

In Linwood Barclay’s new thriller, I WILL RUIN YOU, a teacher’s act of heroism inadvertently makes him the target of a dangerous blackmailer who will stop at nothing to get what he wants. The teacher, Richard Boyle, runs into trouble when he introduces his students to a novel that is not on the curriculum. This subplot inspired Linwood to share his thoughts on book banning and his experiences with it.

In Linwood Barclay’s new thriller, I WILL RUIN YOU, a teacher’s act of heroism inadvertently makes him the target of a dangerous blackmailer who will stop at nothing to get what he wants. The teacher, Richard Boyle, runs into trouble when he introduces his students to a novel that is not on the curriculum. This subplot inspired Linwood to share his thoughts on book banning and his experiences with it. My first experience with the phenomenon of book banning --- which features in a subplot of my new novel, I WILL RUIN YOU --- occurred when I was in the fifth grade.

My first experience with the phenomenon of book banning --- which features in a subplot of my new novel, I WILL RUIN YOU --- occurred when I was in the fifth grade. My next experience with book banning came years later, in my 20s, when I was a reporter for the Peterborough Examiner in Ontario. I came up against a campaign to ban from the curriculum of a high school in nearby Lakefield a novel called THE DIVINERS by Margaret Laurence. Laurence was not only one of Canada’s most celebrated literary writers of the time. She was a good friend and hugely supportive of my dream of becoming a crime novelist one day. (I used to keep her well supplied with Rex Stout and Ross Macdonald novels.) Laurence lived in Lakefield, and this campaign, led by a minister from a local Pentecostal church, was not only maddeningly closed-minded, but also deeply hurtful.

My next experience with book banning came years later, in my 20s, when I was a reporter for the Peterborough Examiner in Ontario. I came up against a campaign to ban from the curriculum of a high school in nearby Lakefield a novel called THE DIVINERS by Margaret Laurence. Laurence was not only one of Canada’s most celebrated literary writers of the time. She was a good friend and hugely supportive of my dream of becoming a crime novelist one day. (I used to keep her well supplied with Rex Stout and Ross Macdonald novels.) Laurence lived in Lakefield, and this campaign, led by a minister from a local Pentecostal church, was not only maddeningly closed-minded, but also deeply hurtful. In my novel, a teacher runs into trouble when he introduces his students to a novel not on the curriculum. The book is THE ROAD by Cormac McCarthy, and one of the teacher’s students is troubled --- but far from traumatized --- by a depiction in the novel of cannibalism. This ends up, as they say, biting our teacher in the butt. One parent questions why the school would force students to read a book that celebrates people devouring one another.

In my novel, a teacher runs into trouble when he introduces his students to a novel not on the curriculum. The book is THE ROAD by Cormac McCarthy, and one of the teacher’s students is troubled --- but far from traumatized --- by a depiction in the novel of cannibalism. This ends up, as they say, biting our teacher in the butt. One parent questions why the school would force students to read a book that celebrates people devouring one another.