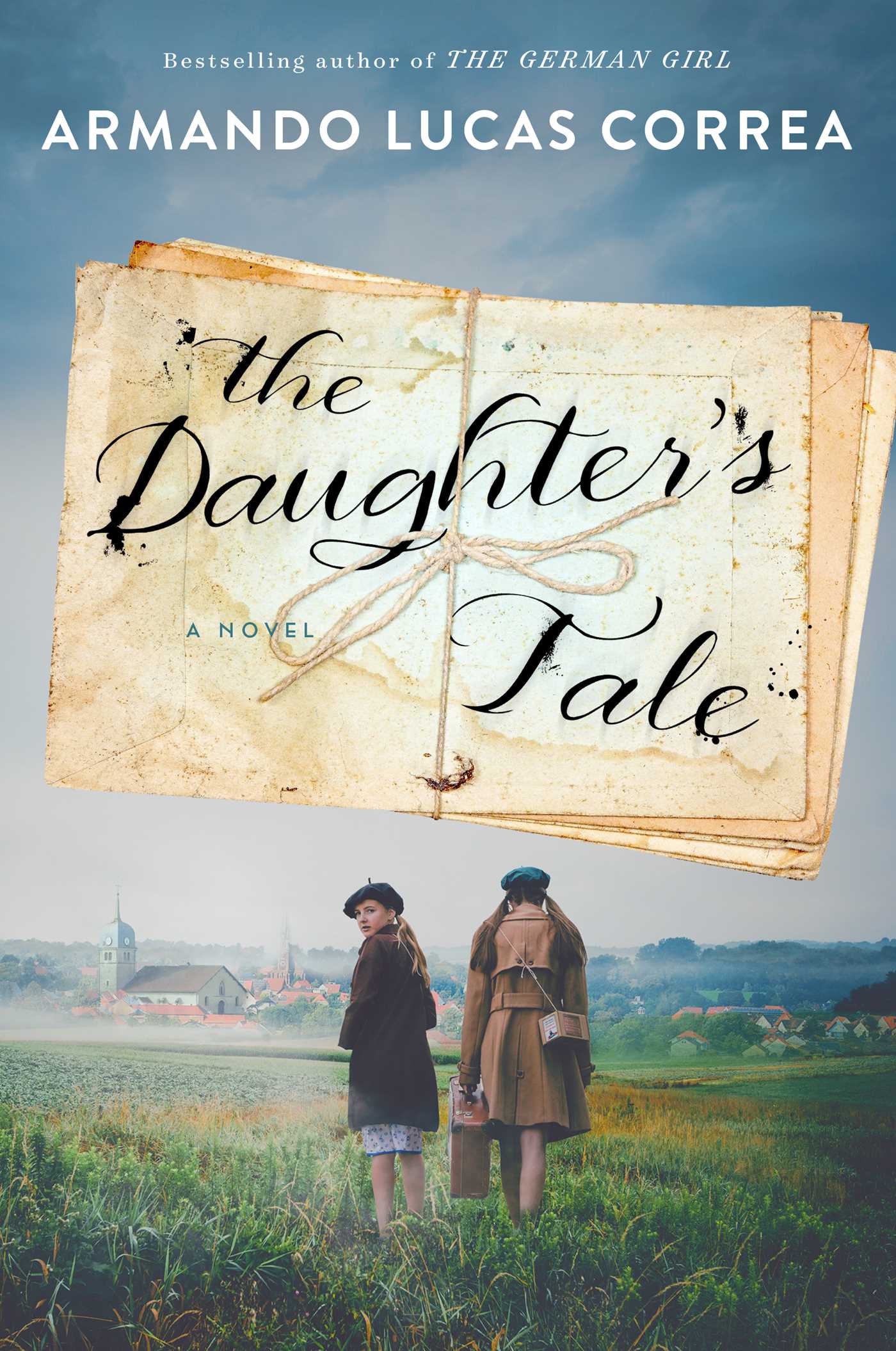

.jpg) Armando Lucas Correa, the internationally bestselling author of THE GERMAN GIRL, recalls a time when his then-eight-year-old daughter started to ask him questions about her heritage. She attends a progressive private school where, according to Armando, “it had become fashionable to create mandatory racial and ethnic affinity groups among students from ‘minority’ backgrounds.” This tendency to attach labels to others and the fear we have of those who are different served as the inspiration for Armando’s new novel, THE DAUGHTER’S TALE, which is now in stores. This unforgettable family saga explores a hidden piece of World War II history and the lengths a mother will go to protect her children.

Armando Lucas Correa, the internationally bestselling author of THE GERMAN GIRL, recalls a time when his then-eight-year-old daughter started to ask him questions about her heritage. She attends a progressive private school where, according to Armando, “it had become fashionable to create mandatory racial and ethnic affinity groups among students from ‘minority’ backgrounds.” This tendency to attach labels to others and the fear we have of those who are different served as the inspiration for Armando’s new novel, THE DAUGHTER’S TALE, which is now in stores. This unforgettable family saga explores a hidden piece of World War II history and the lengths a mother will go to protect her children.

When my eldest daughter was eight, she asked me if she was Black. I told her no, but I can’t be certain. After all, I’m Cuban, the son of Cubans who descended from Spaniards, and I grew up hearing my grandmother say that, in Spain, “everyone was from somewhere else.” I reminded my daughter that on her mother’s side --- my children were conceived through surrogacy with the help of an egg donor --- she has Polish ancestry.

My daughter tried again: “Am I Jewish?”

“You could be,” I answered, telling her that over 500 years ago, many Jews who lived in Spain were forced to convert to Christianity, and I’ve been told that my last name has Sephardi roots.

She wasn’t convinced. “So, I’m Catholic?”

“Not really,” I said. I was baptized in the Catholic Church in Cuba, and our egg donor is also Catholic, I told her, but I couldn’t find a Catholic priest who would baptize her simply because she has two dads.

“And Latina?” she persisted.

Her two dads are Cuban, and we speak Spanish at home. So I said that, yes, at least according to the U.S. Census, that made her Latina.

Satisfied to have finally found a label, she went back to school the next day calling herself “Latina.” My daughter attends a progressive private school in New York City where it had become fashionable to create mandatory racial and ethnic affinity groups among students from “minority” backgrounds. This initiative unleashed an avalanche of outraged emails and launched an online petition against these groups for elementary school-age children. Many parents raised issues of segregation and how the school was forcing children to attach themselves to a culture that didn’t define them. One father questioned why his daughter had to choose between being White or Hispanic when he was Russian and his wife Dominican. His daughter, incidentally, didn’t speak Spanish.

In the Cuba of my childhood, we all had to fill out identification forms, and one mistake could haunt you for life. The most important identifiers then were social status (if you were upper class, you would be ostracized) and religion, where the stakes were even higher: if you said you were Catholic or a Jehovah’s Witness, you could end up in a concentration camp or in jail. In the best-case scenario, you were barred from enrolling in college or fired from your job.

In the Cuba of my childhood, we all had to fill out identification forms, and one mistake could haunt you for life. The most important identifiers then were social status (if you were upper class, you would be ostracized) and religion, where the stakes were even higher: if you said you were Catholic or a Jehovah’s Witness, you could end up in a concentration camp or in jail. In the best-case scenario, you were barred from enrolling in college or fired from your job.

When I arrived in the United States in 1991, I was faced with yet more identification forms, more boxes to tick. This time, the classifications were based on skin color and, by implication, culture.

Around that time, I was researching the Saint Louis, the ocean liner of 900 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany who were turned away from the Port of Havana in May 1939, their permits of disembarkation rejected, most of them sent back to concentration camps in Europe. Haunted by this vile story as a child in Cuba, I always wondered why the Saint Louis passengers, the majority from upper- or middle-class families, had waited so long to flee. One of the survivors of the Saint Louis, who was four years old when she and her family boarded the ship, told me that German Jews like her --- blonde, blue-eyed, rich --- felt almost Aryan and never believed Hitler would consider them anything else.

I ended up writing a novel about the Saint Louis, and every time I was asked to present it to a Jewish group in the U.S., Canada or Australia, someone would always come up to me and whisper in my ear that they were certain I was Jewish. A journalist in Jerusalem, an expert on the origin of last names, even gave me a copy of a dissertation about the Jewish origin of my last name.

Curious to know more about our background, my family recently took a DNA test. As it turned out, my family did not come from one specific place. The majority of our genes came from Portuguese and Spanish stock, as we had presumed. Another notable percentage was French, and the rest was Ashkenazi Jewish and North African.

My daughter, who at 13 has now outgrown the need for blanket labels, sagely pointed out that if those tests had been available in the times of fascism, history would have played out differently. Surely Hitler and his party leadership would have found that they had a percentage of Jewish blood running through their veins.

In the end, my daughter and I know that the root of all this labelling is a toxic fear of those who we consider “other”: the person whose skin color is different, who speaks another language, who has an accent, a different sexual orientation, or a contrasting religious belief. We are terrified of our differences, finding them threatening to our sense of safety and self. But we don’t have to feel this way. We don’t have to let fear win.

This fear that we have of others, of those who are different, is the essence of my new novel, THE DAUGHTER’S TALE, a story of love and hope against all odds. A mother must make a drastic decision and resort to abandonment in order to save her daughter in a world that rejects the other, those it considers are out of the box, that seeks to impose perfection, balance.

We don’t learn from history; we tend to fall into oblivion. The day we accept that we are all different --- and respect those differences instead of trying to assign them names and worth --- is the day that we can finally banish the poisonous idea of the “other.”