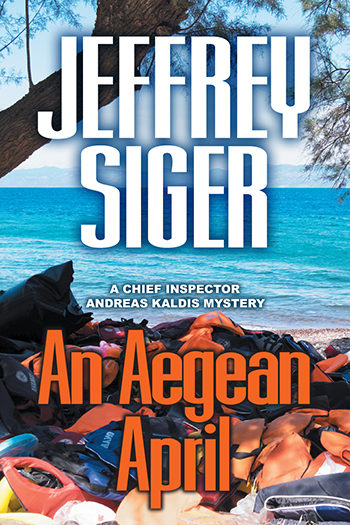

Jeffrey Siger is the author of the internationally bestselling and award-nominated Chief Inspector Andreas Kaldis series, the ninth installment of which, AN AEGEAN APRIL, is now available. In an essay written exclusively for Bookreporter.com, Jeffrey offers some background on the Greek island of Lesvos, which is where his latest book takes place, and “the still extant refugee crisis that spurred me to write a book putting a human face to the moneymakers, human smugglers, fearful families, NGO activists, local islanders, politicians, press and cops caught up in this epic catastrophe.”

"Outstanding... vividly depicts the economic and political issues involved in the European refugee crisis."

– Library Journal, starred review

_1.jpg) For those of you unfamiliar with my work, it all began 10 years ago in Greece with the publication in Greek and English of my first novel, MURDER IN MYKONOS. That book, in what is now a series of nine featuring police inspector Andreas Kaldis, soared to #1 bestseller status in Greece and made theNew York Times “radar list” of hardcover bestsellers in the United States.

For those of you unfamiliar with my work, it all began 10 years ago in Greece with the publication in Greek and English of my first novel, MURDER IN MYKONOS. That book, in what is now a series of nine featuring police inspector Andreas Kaldis, soared to #1 bestseller status in Greece and made theNew York Times “radar list” of hardcover bestsellers in the United States.

When I’m asked about my “new mystery-thriller,” AN AEGEAN APRIL, I say that it takes place on the Greek island of Lesvos and offers a timely exploration of the complexities underlying the flood of refugees across the Mediterranean. In response, I far too often catch an “I thought that was over with there” blank stare, followed by questions about Lesvos and the underlying elements of the refugee crisis.

In the vein of public service, I thought I’d take this opportunity to give a bit of background on both Lesvos and the still extant refugee crisis that spurred me to write a book putting a human face to the moneymakers, human smugglers, fearful families, NGO activists, local islanders, politicians, press and cops caught up in this epic catastrophe.

The northeastern Aegean island of Lesvos, a place of quiet beauty, storied history and sacred shrines, has a reputation as the bird-watching capital of Europe. Possessing the greatest array of wildflowers in Greece, it is one of the world’s largest petrified forests and has long drawn the attention of tourists.

Lesvos ranks as the third largest of Greece’s islands, with roughly one-third of its 86,000 inhabitants living in its capital city of Mytilini. Most Greeks, though, know very little about modern Lesvos and think of it, if at all, as little more than the serene agrarian home of Greece’s ouzo and sardine industries.

That abruptly changed in 2015.

Virtually overnight, thousands of men, women and children fleeing the terrors of their homelands flooded daily out of Turkey across the narrow Mytilini Strait onto Lesvos. Tourists, who had come to holiday on the island’s northern shores, found themselves sitting on the verandas of their beachfront hotels, drinking their morning coffee, and watching in horror as an armada of dangerously overloaded boats desperately struggled to reach land.

Inevitably, tourists stopped coming.

But not the refugees, for they saw no choice but to come. No matter the predators waiting for them along the way: profiteers poised to make billions of euros off the fears and aspirations of desperate souls willing to pay, do or risk whatever they must for the promise of a better, safer existence. In 2015, more than a half-million asylum-seeking migrants and refugees passed through Lesvos, looking to make their way to other destinations in the European Union (EU).

The chaos of the modern world had spun out a rushing storm of profit for human traffickers of every stripe, and Lesvos sat dead center in its path. Greece had not experienced immigration of the current magnitude since the early 1920s, when 1.2 million Greek Orthodox Christians were expelled from Turkey, an event to which most residents of Lesvos traced their ancestors.

What had triggered this nation’s modern migration deluge? Under Greece’s prior government, the Greek Coast Guard intercepted and turned refugee boats back to Turkey, but in early 2015, Greece’s new government ordered its Coast Guard to allow refugee boats to pass into Greece. Germany’s later announcement that it would accept one million Syrian refugees that year made what followed inevitable. From that moment on, it would have been irrational for those caught up in war, Syrian or otherwise, to remain in danger rather than risk a journey toward the promised peace and security of a new life in northern Europe.

Many Lesvos residents joined in doing what they could to help lessen the suffering of the refugees, as did many tourists and off-islanders, but the onslaught soon overwhelmed them. With the arrival of the international media and their cameras, a world outcry arose, bringing non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in to fill the void left by the confluence of EU political paralysis, and Greece’s obvious inability to bear the financial burden of caring for hundreds of thousands of new arrivals while so many of its own 11 million citizens struggled in the depths of a Great Depression-like economic crisis.

Many saw the NGOs’ efforts as admirable but severely wanting in both coordination and execution. What troubled them most was the utter absence of an organized plan for addressing the chronic problem of processing and humanely caring for the masses fleeing to safety in Europe.

Threatened bureaucrats entrenched in doing things their own way feared such change. Worried elected officials concerned with playing to their voters wanted no such plan. And, for sure, human traffickers and their allies, who profited from the status quo, didn’t want one.

But that was then. Wrong.

Today, the rhetoric may be different, and the focus (for now) is on different parts of the world. But the attitude of our allegedly civilized world toward refugees brings to mind the words of Lesvos’s iconic poet, Sappho (630-570 BCE) --- words that might sadly prove to be the refugees’ epitaphic message to us all:

“You may forget but let me tell you this: someone in some future time will think of us.”