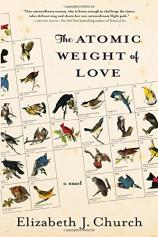

Elizabeth J. Church practiced law for over 30 years, and her debut novel, THE ATOMIC WEIGHT OF LOVE, is proof that it’s never too late to pursue one’s dreams. It’s a moving story of ambition and identity, and the women who sacrificed their careers so that their husbands could pursue their own. It’s also a story that will ring familiar to any woman who has had to choose between what she loves and who she loves. Elizabeth’s own mother, a brilliant biologist, faced similar obstacles, but was ultimately able to pursue her own dreams --- and encourage a fierce, ever-growing love of reading in her daughter along the way.

Elizabeth J. Church practiced law for over 30 years, and her debut novel, THE ATOMIC WEIGHT OF LOVE, is proof that it’s never too late to pursue one’s dreams. It’s a moving story of ambition and identity, and the women who sacrificed their careers so that their husbands could pursue their own. It’s also a story that will ring familiar to any woman who has had to choose between what she loves and who she loves. Elizabeth’s own mother, a brilliant biologist, faced similar obstacles, but was ultimately able to pursue her own dreams --- and encourage a fierce, ever-growing love of reading in her daughter along the way.

My mother remained a woman of insatiable curiosity until her death at age 92. She instilled in me a pulsing need to know fed by books and the worlds contained in those books.

A good deal of what my mother did for me with respect to reading was not atypical of what other mothers in Los Alamos, New Mexico, did for their children in the 1950s. Homes were filled with books, and television viewing (three truncated network stations and PBS, black and white only, thank you very much, with constant horizontal hold problems) was limited. My parents dedicated nearly an entire wall of our living room to thickly populated bookshelves, and she read to us --- nursery rhymes, fairy tales (the lighthearted as well as the Grimm’s versions). When my second grade teacher held a book-reading contest, I had to prove I’d truly read each book, and so my mother listened to me read aloud while she cooked or did the dishes. She also listened to my complaints that my nearest competitor was reading shorter books than I and so was gaining on me; I wanted to know how to demand that my teacher ensure a fair contest (the budding lawyer showed her face).

We made regular, weekly trips to the town library, where very early on I was permitted to check out as many Beatrix Potter books as I could carry. I so loved them, not only for the stories, but also for the slick white covers with their pastel-toned drawings, the richness of the heavy paper stock on which the books were printed. To my unending delight, she entered me in every bookworm summer reading program. One of my favorite birthday gifts was a Webster’s dictionary.

There were, however, a few things my mother did differently. When I ventured into the adult area of the library and was nabbed by a librarian, told I could not even walk amongst those shelves, let alone check out any of those books, my mother told the librarian in no uncertain terms that I was smart enough to read those books and that she’d be sure I did exactly that. She also suggested books: HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY, which had so much of her Pennsylvania coal-mining at its foundations; THE SCARLETT PIMPERNEL; and, of course, the Brontës. She would not buy me the Nancy Drew books I so coveted; those, I had to pay for with my allowance so that I would know the value of books and learn to take good care of them.

My mother did draw the line at some titles, and so by junior high school I was surreptitiously removing them from her bedroom shelves while she was at work, carefully replacing them before she got home: THE VALLEY OF THE DOLLS (oh my!); THE NAKED APE (not nearly as scintillating as I’d hoped).

Although my mother grew up impoverished, once my brothers and I left home, she managed to travel all over the world. She loved reading books that took place in countries she’d visited, and she adored ferreting out errors the author had made about some inconsequential detail. In her final year of life, we would talk books incessantly while she sat in her chair in the overheated, claustrophobic room of her assisted living facility. She’d tell me what she’d liked or not in a particular writer (“I don’t need to know what the character’s wearing! I want for the action to move along! Old people like me don’t have all day!”). At that point in her life, she tended toward more nonfiction, still demonstrating her eternal hunger for worlds the men of her generation had been permitted to explore while she’d been denied similar opportunities (aeronautic flight, war). She was opinionated and bright and driven and enormously independent. But most of all, she was a voracious reader with a lively mind.

The fact that I became the same sort of reader may be a matter of genetics as well as environment, but I have no doubt that I owe my love of words and what they can achieve in terms of understanding, inspiration and depth of emotion to my mother.