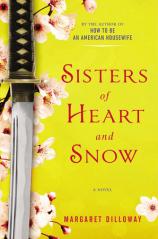

It’s easy, for writers and readers alike, to take for granted the art of oral storytelling. Not so for award-winning author Margaret Dilloway, whose mother would often tell her Japanese fairy tales from memory when she was young. Margaret’s own daughters are already avid readers, who seem to be carrying on the family tradition of dramatic recitation. Margaret’s latest book, SISTERS OF HEART AND SNOW --- the poignant story of estranged sisters, forced together by family tragedy --- is in stores now.

It’s easy, for writers and readers alike, to take for granted the art of oral storytelling. Not so for award-winning author Margaret Dilloway, whose mother would often tell her Japanese fairy tales from memory when she was young. Margaret’s own daughters are already avid readers, who seem to be carrying on the family tradition of dramatic recitation. Margaret’s latest book, SISTERS OF HEART AND SNOW --- the poignant story of estranged sisters, forced together by family tragedy --- is in stores now.

My mother wasn’t much of a reader. She wasn’t comfortable reading things in English, and she had just a few Japanese books stashed away. The only adult fiction book I ever saw on our bookshelf had been left there by my paternal grandmother during an early 1970s visit.

But my mother was a storyteller. I’d beg her to tell and re-tell the Japanese fairy tales she knew so well. “The Bamboo Cutter and the Moon Child.” “Momotaro the Peach Boy.” She had a lilting voice that rose and fell dramatically as she told the exciting parts. Because she never read to me otherwise, I treasured this time with her.

To me, her stories were just as thrilling as reading about Dorothy and Ozma ruling Oz, or Pippi Longstocking sailing the seas. Because of her, I knew about the transformative power of the voice, about oral storytelling. These stories taught me how to see the worlds in my head, instead of in picture books.

When I started kindergarten, I came home distressed because I hadn’t learned how to read on the first day. I was consumed with jealousy over the kids who already knew how to pick up the little books in the classroom and read about a squirrel losing his red sock. “You’ll get it soon,” my mother soothed me, and indeed, once my reading comp clicked on, I read voraciously.

My mother sanitized all the books I brought home from the library, spraying the clear library binding with Lysol and wiping it with a paper towel. “They’re full of germs! Every time you check one out, you get sick,” she said, and showed me the paper towel, which was indeed black with grime.

She had to disinfect quite a few, because I won every summer library reading contest for quite a few years in a row.

I wanted our children to love reading as much as I do. I began reading to each of my own three kids while they were in utero. My husband and I saved our favorites from childhood. For me, GOOD NIGHT, MOON. For him, IF I RAN THE CIRCUS. When they were babies, I made my own books, cutting out pictures from magazines that they could flip through, making up my own stories to go with the pictures. We went through every Eric Carle and Richard Scarry and Jon Sciezka picture book there was.

And I told them the stories my mother had told me.

Our house is different from my parents’ house. This is a house filled with books, with tomes left bookmarked on the couch, open and covered with crumbs on the dining table, bursting out of shelves, stacked high on nightstands.

My 15-year-old daughter has always loved to read, and amid her AP-heavy schedule, she still makes time to go to the library to check out old Agatha Christies and Neil Gaimans. My 13-year-old son favors nonfiction and funny realistic books, as well as favorites like the Lord of the Rings series that both my husband and brother liked at his age.

A few nights ago, I tucked my nine-year-old daughter into bed. Amid the stuffed animals on the foot of her bed are a dozen books. The manuscript for my children’s book, XANDER AND THE LOST ISLAND OF MONSTERS, is rubber-banded next to her pillow.

This is normal for her. She likes her books close by, heavy at her feet.

Later she came downstairs. “I can’t sleep.”

“Go read,” I told her. “You’ll get tired soon enough.”

But when I went up a few minutes later, I heard a variety of British accents coming out of her room. Her older sister was in there, reading her Harry Potter in perfect character voices, until the younger one fell asleep.