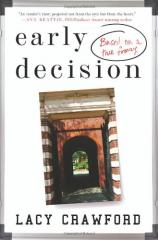

Lacy Crawford doesn’t remember her mother reading bedtime stories to her; that job seemed to have been appropriated by her father at some point between the time she was an infant and the time she could read to herself. But she does remember her mother’s keenly detailed recipe cards --- and the stories they told indirectly. From her mother, Lacy learned to observe and record, and to find the story off the page. Her book, EARLY DECISION: Based on a True Frenzy, was published last year.

Lacy Crawford doesn’t remember her mother reading bedtime stories to her; that job seemed to have been appropriated by her father at some point between the time she was an infant and the time she could read to herself. But she does remember her mother’s keenly detailed recipe cards --- and the stories they told indirectly. From her mother, Lacy learned to observe and record, and to find the story off the page. Her book, EARLY DECISION: Based on a True Frenzy, was published last year.

I don’t remember my mother reading to me. I know she did, particularly when I was tiny; but all at once I learned to read to myself, my baby brother was born, and my mom went back to school to launch her career, and from that point on, my father handled bedtime. It’s his voice I remember in the evenings. And the books were wonderful, all the standards: THE GIVING TREE and NOW WE ARE SIX, and THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS, all the way through.

Before the stories, though, we had a family dinner. Every night. Mom was a prodigiously talented cook who had formally trained at the Cordon Bleu School in Paris, but this was just top-dressing: she’d learned to cook at her grandmother’s elbow, in a seething hot kitchen in St. Louis. Later she’d learned from her own mother and from various household helpers in the countries where she grew up: first Cuba, then Italy, then Switzerland and the UK. My grandmother’s husband --- my mother’s stepfather --- moved his family regularly, as his “consulting” work took him to conflict areas in postwar Europe and North Africa for long periods of time. He was cagey and a poor correspondent. After he died, it emerged that he was most likely a spy.

My mother and her mother, then, were tasked over and over again with making a home. They did it in foreign countries and foreign languages, and they did it largely alone. My grandmother traveled with a yellowed set of index cards bearing recipes from her own Depression-era childhood on a Texas ranch (a typical first step: “Kill chicken”), and to these were added new cards from each home they kept. Like her mother before her, my grandmother was fanatical about recording the provenance of each recipe. Notes on its success were often included (“August 12, 1965: Wonderful for ladies on hot day, serve w/sun tea”) and adjustments were added, ongoing, as situations required: to “350 degrees” the addition of “gas mark four,” for the London oven; “Anna uses leeks not onions” to register the objections of the young German cook they had for a time in Rome.

As a girl, I hovered while my mother cooked. She’d pull a single stained card from the box and set it out. But I knew she had each recipe by heart. The point was to invite me to read, and thereby to surface a story. I studied the shorthand and I asked; my mother, her hands working all the while, told me what was true.

The ladies at that sweltering luncheon in 1965 included a woman my step-grandfather was sleeping with.

The London kitchen overlooked Hyde Park, where my mom walked as a teenager, anorexic, her eyes raccooned in kohl, the years she modeled, the last long days before she met my father, when she was only 17.

Anna, misunderstanding a caged animal, cooked and served the family my mother’s pet rabbit.

If each card was the seed of a meal, of a coming together at table, in its notes was also the record of loss --- of the forces a mother, any mother, is working against, when she gathers her family every night to share a meal. This was deliberate. I’d sit on the kitchen counter, feet dangling, and feel my heart rise to the excitement of the stories --- and beat heavy, too, thinking that a woman’s work was not so simple as this, that nurture was not always enough.

I read to my children every night. I have no daughter, and I delight in watching my boys learn to sink deep into the shared dream of the stories we read, to let themselves be carried. These melodies of suspense and resolution are essential to our human hearts. But I learned from the recipe cards an equally vital set of truths: that the voices off the page are often the ones who see the most; that there can be no sustenance without grief; that a story, to live, must be told; that the smallest details can feel holy. Observe, record. This is the work of the storyteller and the mother both. Gather your loved ones, and fill their bowls.

But kill the chicken first.