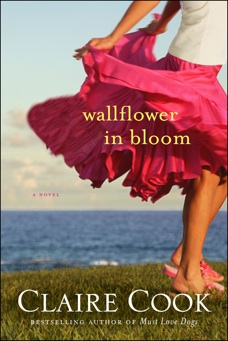

Claire Cook wrote her first novel in her minivan when she was 45. At 50, she walked the red carpet at the Hollywood premiere of the adaptation of her second novel, MUST LOVE DOGS, starring Diane Lane and John Cusack. She is now the bestselling author of eight novels, with a ninth, WALLFLOWER IN BLOOM, coming from Touchstone in June. Find out more at ClaireCook.com and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Claire Cook wrote her first novel in her minivan when she was 45. At 50, she walked the red carpet at the Hollywood premiere of the adaptation of her second novel, MUST LOVE DOGS, starring Diane Lane and John Cusack. She is now the bestselling author of eight novels, with a ninth, WALLFLOWER IN BLOOM, coming from Touchstone in June. Find out more at ClaireCook.com and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

On a Saturday morning in 1966, I knocked at my friend’s front door.

“My mother died,” I said the second she opened it.

“No, sir,” she said, though since this was a Boston suburb, it sounded more like “No, suh.” Today, she would have said: No way.

“Swear to gawd,” I said. Translation: Way.

“Liar,” she said. “You’re making it up.”

Sadly, I wasn’t. The day before, my healthy mother’s flu had turned into sepsis. She slipped into a coma at the hospital and never came out, leaving five children under the age of twelve motherless. Neighbors gathered up the toddlers, met the rest of us in our driveway after school, and brought us home with them. They didn’t say much, but I knew my first pajama party, scheduled for that evening, was definitely not going to happen.

The funeral took place on Valentine’s Day, also my birthday. Back at the house afterwards, someone put candles on a dull chocolate cake, so unlike the heart-shaped candy-studded pink ones my mother had baked for my other ten birthdays, and mourners dressed in black sang Happy Birthday to me.

Even though I’d only been eleven for a few hours, I knew my mother would have found this incredibly tacky, and would never have let it happened if she were alive. She was the one who’d always been there, who’d seen me as the family writer, who’d edited my first published work that appeared in the Little People’s Page of the Sunday newspaper at the ripe old age of six.

I can’t remember blowing out the candles, but I must have. After that people started tucking birthday bills in the pocket of my dress, as if I were a prepubescent stripper-in-training. Most were ones and fives, but my godfather, whom I never saw again, gave me a hundred dollar bill. It seemed like a fortune to me, but I would have traded it for my mother in a heartbeat.

Time heals most wounds, and the rest you compartmentalize. Over the years, I’ve talked to other women who lost their mothers at an age when their mother was still the sun and the moon and their favorite hula hoop all rolled into one, yet they were also old enough to know they were on the cusp of really needing her to walk them through that first bra and period. The loss becomes the defining sadness of your life, and long after everyone else would imagine you’re over it, you’re still numb.

By the time I came out of my post traumatic fog, I was an adult and I really wanted to know what my mother had been like -- as a person, a woman, a friend. But the people who might have told me were now either dead or long gone.

Then one night on book tour near my mother’s hometown, a woman about my age waited in my signing line with an older woman in a wheelchair. As the younger woman handed me a copy of my latest novel, she told me her mother had something to say to me.

I leaned over the wheelchair and smiled.

“I went into labor with my son, Jimmy, in the middle of a blizzard.”

It was a hot summer night, but a winter chill ran down my spine.

“The snow came on so fast, my husband couldn’t get home. I called the ambulance. I called the police. Nobody came. Then I called your mother. She walked through the snow to my house. ‘Put your coat on,’ she said. ‘It will be the adventure of a lifetime.’ And she walked me all the way to the hospital, laughing and joking the whole time. She was Jimmy’s godmother, you know.”

I reached out to hold her cool, dry hand, and it felt lighter than air.

She giggled. “Your mother had more godchildren than you could shake a stick at. She was the most generous friend in the world.”

I wasn’t really surprised. I’d been old enough to know my mother was kind and big-hearted, to remember the huge pile of cards and letters, with family photos tucked in, at Christmas.

The child inside me felt my mother’s loss all over again. But the woman I’d become was overjoyed to learn that my mother’s spirit could live on for decades in the heart of a friend.