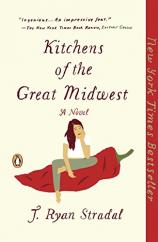

Author Talk: July 30, 2015

Although he now lives in Los Angeles, J. Ryan Stradal was born and raised in Minnesota, so it’s no surprise that his debut novel is titled KITCHENS OF THE GREAT MIDWEST. It’s one of the most hotly anticipated books of the summer, about a young woman with a once-in-a-generation palate who becomes the iconic chef behind the country’s most coveted dinner reservation. In this interview, Stradal reveals why he chose to tell each chapter from a different character’s point of view and how that enabled him to capture the zeitgeist of the Midwest. He also discusses his philosophy when it comes to foodie culture, how food contributes to identity and community, and why he would never challenge a Midwesterner to a bake-off.

Question: What inspired the story of Eva Thorvald?

J. Ryan Stradal: Many things --- perhaps too many to list here --- but chief among them is the fact that I relate to her childhood. Like her, I was a child with passionate interests, and I didn’t often have many people with whom I could share them. I depended on concerned adults --- in my case, the teachers and librarians at school --- for guidance. I know what it’s like to be driven by obsessions not shared by my classmates, and what it’s like to be bullied on the school bus, though in the latter case I never did experience anything like Eva’s satisfying revenge.

Much of the details of her adult life as a chef were influenced by the time I’ve spent with Patricia Clark and Amy Schabert Kovacs, two culinary professionals I have the honor of calling dear friends. They also taught me a lot about the life of a chef behind the scenes, some of which made it into Eva’s story.

Q: You’ve chosen to tell this novel through shifting points of view, including those of supporting characters. How did you decide on this narrative structure?

JRS: When I decided to set a book in the Midwest, I knew I would never please everyone with the characterizations, because there’s no prototypical Midwesterner. I also wanted Eva’s adult career to be cloaked in mystery and hearsay, and I felt that telling the story from multiple points of view would both allow me to introduce a variety of Midwestern characters while simultaneously keeping Eva at a bit of a distance.

Q: Some people might argue that the Midwest isn’t normally associated with great kitchens. Can you talk about your title and how you came to use it?

JRS: No great kitchens? Not in my experience! For starters, I would never go up against a Midwesterner in a bake-off.

Even though I grew up in Minnesota and attended college outside Chicago, I don’t think my Midwestern bias is merely sentimental. The people I know who are serious about food in the Midwest are as simultaneously daring, thoughtful, conscientious and skillful as chefs anywhere. They also have a ton of heart, patience and resilience. The Midwest can be a tough place to live much of the year, and having a talented and crowd-pleasing cook at home or nearby is a crucial morale booster during both those months where your snot is frozen and those weeks when you’re eaten alive by mosquitoes.

Q: Eva Thorvald often seems to hover in the background of the story, yet she takes on a legendary quality. How, as an author, do you go about creating a larger-than-life character?

JRS: A writing professor of mine at Northwestern University, David Tolchinsky, taught me that a reader won’t often believe what a character says about himself, but will be much more inclined to believe what other characters say about him. Making this hearsay particularly grand contributed a lot to Eva’s legend that I don’t think would have been as effective coming from her own mouth. I also felt that the adult Eva we directly experience had to stand in contrast to this legend. When we see her as an adult, she’s unpretentious, casual, direct and extremely kind. She has her guard up during crucial moments, but otherwise I think in person she’s open and sweet, and I love seeing how her behavior mixes with the anecdotal Eva to create a fuller portrait of the woman.

Q: Where did you find the recipes in the book? Which, if any, have personal value for you?

JRS: Many of the recipes --- five of the eight, to be precise --- are inspired by recipes from a book compiled by the women of First Lutheran Church, in my grandmother’s hometown of Hunter, North Dakota. My great-grandmother and two great-aunts both have recipes in this book --- and they all have personal meaning to me. This was the food I grew up on in Minnesota.

Q: Eva never really knows her real parents, yet she is the embodiment of their hopes and dreams --- whether through genetics or early exposure or by coincidence. How do you explain it?

JRS: A mixture of the first two --- genetics and early exposure --- that she’s also coupled with a mission to create an identity for herself in a larger world. It’s no accident that the first things that define her as a chef are varieties of hot chili pepper, which aren’t exactly native to the upper Midwest. Like a lot of alienated, intelligent, passionate and bullied kids, she attaches her sense of identity to a world outside the only one she’s ever known, and finds a small community outside her immediate family to support her interest.

Q: You touch on some very contemporary food culture debates: the elevation of authenticity and heirloom traditions versus cynical “artisan” marketing; an obsession with flavor versus a preoccupation with health; the desire to celebrate local food cultures versus the need for convenience. What is your take on these issues as an eater and (presumably) home cook?

JRS: I wanted to capture sympathetically differing points of view in this novel because, frankly, I adhere to both the traditionalism of Pat Prager and the epicurism of Octavia Kincade, and sometimes, the easy indifference of Jordy Snelling. It depends on, as with so many things, context and company. While I have culinary preferences, I am careful not to make them demands.

I do think that knowing the source of one’s food is interesting and useful, but at its most extreme, it can also seem awfully precious. I love how the folks in “Portlandia” have hilariously skewered its excesses. I grew up in Pat Prager’s world, however, and so I will never fully leave it.

Q: You capture so many different voices in the narrative. Which ones came easily to you and which ones were harder to capture?

JRS: Jordy Snelling took the most time. His was the second chapter I wrote, but I labored to get him just right for a long time. (I had a close consultant on this one, too.) Octavia Kincade’s chapter I knocked out over a weekend and barely touched during editing. For some reason, that character was extremely easy for me to write. I have a deep well of sympathy for her.

Q: The final feast in the book serves as an emotional catharsis of sorts for the characters eating it. What were the challenges in capturing such an evocative meal in writing?

JRS: For starters, I’ve never had a dinner quite like that myself, where I’d be reconciling the cost of the meal with the meal itself during the experience. I tried to get into the heads of diners who were, to varying extents, being instructed on the value of The Dinner by its price tag, and others who simply juxtaposed the experience with their own expectations. As breathtaking as Eva’s food may be, I feel that these factors would inspire exaggerated reactions like the ones I characterized, and perhaps also responses that would be much more extreme. In Cindy’s case, I also had the challenge of describing a parent eating her child’s cooking for the first time in this heightened context; synthesizing all of this was a dizzying amount of work. I did my best.

Q: The reader walks away with the sense of what could have been and how sometimes small details can weigh heavily on the future --- particularly in the case of Octavia Kincade, for instance. Which of these alternate possible paths did you actually wrestle with in deciding your characters’ fates?

JRS: Well, I wrote a few chapters early on that didn’t make the book, mostly because they didn’t tell us enough about Eva. I felt that her evolution is at the center of this novel and every chapter had to tell us something new about her. I really had room for only two chapters --- Pat’s and Jordy’s --- where Eva is a featured extra. Any more than that, I felt, would really test my readers. In one of these excised chapters about sheng pu’erh tea, Ros Wali plays a much more significant role. Another chapter dealt with a man who grew lemon cucumbers, which is a wonderful heirloom cucumber, but not especially common. So when I think of paths not taken in this book, I often think in terms of ingredients; there were so many I considered. Rhubarb, sadly, was never on the table, simply because the final dinner happened well after peak spring rhubarb season. Next time, perhaps.

Q: At the heart of this story is the notion that “food is life.” Can you talk about what this means for you, and what it means for Eva?

JRS: Food, for Eva, and for many people, is what brings people together like nothing else; she would say it’s a lingua franca, and an expression of the chef’s identity, but also, when done with care, an expression of love. She’s become uncompromising about her food because she knows how it affects people when done well. To her, good food is an art, a science, a gift, a morale booster and an embrace. In the absence of her father and mother, Eva has assembled a family of choice through her passion for food, and drawn people to her because of her culinary talent. I’m fortunate to know people like Eva in real life, and the best year of my life so far was when I was getting up every morning to write this book and spend more time in her world.