Excerpt

Excerpt

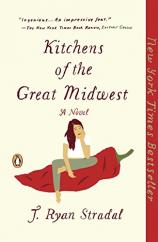

Kitchens of the Great Midwest

LUTEFISK

Lars Thorvald loved two women. That was it, he thought in passing, while he sat on the cold concrete steps of his apartment building. Perhaps he would’ve loved more than two, but it just didn’t seem like things were going to work out like that.

That morning, while defying a doctor’s orders by puréeing a braised pork shoulder, he’d stared out his kitchen window at the snow on the roof of the Happy Chef restaurant across the highway and sung a love song to one of those two girls, his baby daughter, while she slept on the living room floor. He was singing a Beatles song, replacing the name of the girl in the old tune with the name of the girl in the room.

He hadn’t told a woman “I love you” until he was twenty-eight. He didn’t lose his virginity until he was twenty-eight either. At least he’d had his first kiss when he was twenty-one, even if that woman quit returning his calls less than a week later.

Lars blamed his sorry luck with women on his lack of teenage romance, and he blamed his lack of teenage romance on the fact that he was the worst-smelling kid in his grade, every year. He stunk like the floor of a fish market each Christmas, starting at age twelve, and even when he didn’t smell terrible, the other kids acted like he did, because that’s what kids do. “Fish Boy,” they called him, year round, and it was all the fault of an old Swedish woman named Dorothy Seaborg.

• • •

On a December afternoon in 1971, Dorothy Seaborg of Duluth, Minnesota, fell on the ice and broke her hip while walking to her mailbox, disrupting the supply line of lutefisk for the Sunday Advent dinners at St. Olaf’s Lutheran Church. Lars’s father, Gustaf Thorvald—of Duluth’s Gustaf & Sons bakery, and one of the most conspicuous Norwegians between Cloquet and Two Harbors—promised everyone in St. Olaf’s Fellowship Hall that there would be no break in lutefisk continuity; his family would step in and carry on the brutal Scandinavian tradition for the benefit of the entire Twin Ports region.

Never mind that neither Gustaf, his wife, Elin, nor his children had ever even seen a live whitefish before, much less caught one, pounded it, dried it, soaked it in lye, resoaked it in cold water, or done the careful cooking required to make something that, when perfectly prepared, looked like jellied smog and smelled like boiled aquarium water. Since everyone in the house was equally unqualified for the job, the work fell to Lars, age twelve, and his younger brother Jarl, age ten, sparing the youngest sibling, nine-year-old Sigmund, but only because he actually liked the stuff.

“If Lars and Jarl don’t like it,” Gustaf told Elin, “I can count on them not to eat any. It’ll eliminate loss and breakage.”

Gustaf was satisfied with this reasoning, and while Elin still thought it was a mean thing to do to their young sons, she said nothing. Theirs was a mixed-race marriage—between a Norwegian and a Dane—and thus all things culturally important to one but not the other were given a free pass and critiqued only in unmixed company.

• • •

Yearly intimate contact with their cultural heritage failed to evolve the Thorvald boys’ sensibilities. Jarl, who still ate his own snot, much preferred the taste of boogers to lutefisk, given that the consistency and color were the same. Lars, meanwhile, was stumped by the old Scandinavian women who walked up to him in church and said, “Any young man who makes lutefisk like you do is going to be quite popular with the ladies.” In Lars’s experience, lutefisk skills usually inspired revulsion or, at best, indifference among prospective dates. Even the girls who claimed they liked lutefisk didn’t want to smell it when they weren’t eating it, and Lars couldn’t give them much of a choice. The once-anticipated holiday season had become for Lars a cruel month of stench and rejection, and thanks to the boys at school, its social effects lingered long after everyone’s desiccated Christmas trees were abandoned by the curbside.

• • •

By the time Lars was eighteen, whatever tolerance he’d once had for this uncompromising tradition had long eroded. His hands were scarred from several Advents of soaking dried whitefish in lye, and every year the smell clung harder to his pores, fingernails, hair, and shoes, and not just because their surface areas had increased with maturity. Lars had also grown to become a little wizard in the kitchen, and by his unintentionally mastering the tragic hobby of lutefisk preparation, its potency was skyrocketing. Lutherans were driving from as far away as Fergus Falls to try the “Thorvald lutefisk,” and there wasn’t an attractive young woman among any of them.

As if to mock him further every year, Lars’s dad would shove a forkful of the crap in his face each Christmas.

“Just a bite,” Gustaf would say. “Your ancestors ate this to survive the long winters.”

“And how did they survive lutefisk?” Lars asked once.

“Take some pride in your work, son,” Gustaf said, and took away his lefse in punishment.

• • •

In 1978, Lars graduated from high school and got the heck out of Duluth. His grades could’ve gotten him into a nice Lutheran school like Gustavus Adolphus or Augsburg, but Lars wanted to be a chef, and he didn’t see what good college would do him other than to delay that goal by four years. Instead he moved down to the Cities, looking for a girlfriend and for kitchen work in whatever order, requiring only that no one insist he make lutefisk. That attitude sure left a lot more options open than his father had predicted.

After a ten-year unpaid apprenticeship at Gustaf & Sons, Lars was already skilled at baking—arguably the most difficult of all culinary duties—but didn’t want to fall back on that. Because he only chose jobs that could teach him something, and went on dates about as often as a vegetarian restaurant opened near an interstate highway, he gained a pretty decent handle on French, Italian, German, and American cuisine in just under a decade.

By October 1987, as his home state was enraptured by the Twins winning their first World Series ever, Lars had earned a job as a chef at Hutmacher’s, a trendy lakeside restaurant that attracted big celebrities, like meteorologists, state senators, and local pro athletes. For years, it was said, a Twins player could enjoy his meals at Hutmacher’s unremarked and unmolested, but by the week Lars was hired, jubilant ballplayers were regularly turning the late shift into an upbeat party.

Amid the circumstance of a long-suffering sports team’s success, the strange joy of it all spread through the restaurant. It was during these happy weeks when Cynthia Hargreaves, the smartest waitress on staff—she gave the best wine pairing advice of any of the servers—seemed to take an interest in Lars. By this time, he was twenty-eight, growing a pale hairy inner tube around his waist, and already going bald. Even though she had an overbite and the shakes, she was six feet tall and beautiful, and not like a statue or a perfume advertisement, but in a realistic way, like how a truck or a pizza is beautiful at the moment you want it most. This, to Lars, made her feel approachable.

When she came back to the kitchen, the guys would all openly check her out, but Lars refrained. Instead, he’d look her in the face while he told her things like, “Tell them it’ll be five more minutes on that veal,” and “No, I will not hold the garlic—it’s pesto.”

“Oh, you can’t make a sauce with just pine nuts, olive oil, basil, and Romano?” she asked.

He was a bit impressed that she knew the other ingredients off the top of her head. Maybe he shouldn’t have been, but it just wasn’t the kind of thing he expected people outside a kitchen to know. He knew he must have communicated this to her when he saw how she was smiling back at him knowingly, like he had been caught in the act of something.

“Well, you know, I can try,” he said. “But then it’s not pesto, it’s something else.”

“How fresh is the basil?” she asked. “Pesto lives or dies by its basil.”

He admired her decisive way of phrasing that incorrect opinion. It was actually the preparation that determined its quality; proper pesto, he had learned during a previous job at Pronto Ristorante, is made with a mortar and pestle. It makes all the difference.

“It’s two days old,” he said.

“Where’d you get it from? St. Paul Farmers’ Market?”

“Yeah, from Anna Hlavek.”

“Oh, you should get it from Ellen Chamberlain. Ellen grows the best basil.”

Such wonderfully erroneous food opinions! This was getting Lars all riled up. Still, in his Minneapolis years, liberated from both his lutefisk stench and its reputation, he’d driven women away due to what they called his “eagerness,” and he couldn’t allow that to happen again.

“Oh, she does, now?” he asked her, continuing to work, not looking up at her.

“Yeah,” she said, stepping closer to him, trying to keep him engaged. “Anna grows sweet corn in the same plot as her basil. You know what sweet corn does to soil.”

She had a point, if that were true. “I didn’t know Anna grew sweet corn.”

“She doesn’t sell it to the public.” She smiled at him again. “And I’ll tell my customer yes on the garlic-free pesto, anyway.”

“Why?”

“I want to see you work a little harder back here,” she said.

He couldn’t help it—he was in love by the time she left the kitchen—but love made him feel sad and doomed, as usual. What he didn’t know was that she’d suffered through a decade of cool, commitment-phobic men, and Lars’s kindness, but mostly his effusive, overt enthusiasm for her, was at that time exactly what she wanted in a partner.

• • •

Cynthia was pregnant, but not showing, by the time they were married in late October 1988. Lars was still a chef at Hutmacher’s, and she was still their most popular waitress, but despite the storybook romance that had flourished within their establishment, the owners refused to shut the restaurant down on a Saturday to host the wedding reception.

Lars’s father, still infuriated that his eldest son had abandoned both the family bakery and the responsibility of supplying lutefisk for thousands of intransigent Scandinavians, boycotted the wedding and refused to support any aspect of it. If Lars was having his mother’s first grandchild, she might have been inspired to help, but instead Elin was already busy with Sigmund’s two kids; naturally, the one brother who’d never made lutefisk in his life had lost his virginity, and fruitfully, by age seventeen.

• • •

The couple honeymooned in the Napa Valley, which was still flush from the shocking Judgment of Paris more than a decade earlier and happily maturing into its new volume of wine tourism. Lars had never experienced a wine tasting before, and while her new husband threw back the one-ounce pours, Cynthia consumed everything on the labels, the vineyard tours, and the maps. It was her first trip to California, and even completely sober, her body swooned at the sight of a grapevine and her soul flourished in the jungle of argot: varietal, Brix, rootstock, malolactic fermentation. In the rental car, with his eyes closed while trying to sleep off a surfeit of heavy afternoon reds, Lars could feel her smiling as she drove him and their unborn child through the shimmering California hills.

“I love this so much,” she said.

“I love you, too,” he said, though that was not what she meant.

• • •

They’d agreed, if it was a boy, that Lars would name the baby, and if it was a girl, Cynthia would. Eva Louise Thorvald was born two weeks before her due date, on June 2, 1989, coming into the world at an assertive ten pounds, two ounces. When Lars first held her, his heart melted over her like butter on warm bread, and he would never get it back. When mother and baby were asleep in the hospital room, he went out to the parking lot, sat in his Dodge Omni, and cried like a man who had never wanted anything in his life until now.

• • •

“Let’s give it five or six years before we have another one,” Cynthia said, and got herself an IUD. Lars had been hoping for at least three kids, like in his own family, but he supposed there was time. He tried to impress upon Cynthia the fact that having multiple kids means at least one of them will stick around to make sure that you don’t die alone if you fall in the shower or trip on your basement staircase. He pointed out how after he and Jarl had gotten out of Duluth, their middle brother, Sigmund, had taken over both the bakery and the extraordinary demands of their dying parents, and how that was working out super for everybody. This line of argument was not compelling to his twenty-five-year-old wife. Cynthia wanted to get into wine.

• • •

In the same fashion that a musical parent may curate their child’s exposure to certain songs, Lars had spent weeks plotting a menu for his baby daughter’s first months:

Week One

NO TEETH, SO:

1.Homemade guacamole.

2.Puréed prunes (do infants like prunes?)

3.Puréed carrots (Sugarsnax 54, ideally, but more likely Autumn King).

4.Puréed beets (Lutz green leaf).

5.Homemade Honeycrisp applesauce (get apples from Dennis Wu).

6.Hummus (from canned chickpeas? Maybe wait for week 2.)

7.Olive tapenade (maybe with puréed Cerignola olives? Ask Sherry Dubcek about the best kind of olives for a newborn.)

8.What for protein and iron?

Week Two

STILL NO TEETH, UNLESS WE’RE IMPROBABLY FORTUNATE, BUT WHAT THE HECK ANYWAY:

1.Definitely hummus.

2.The rest, same as above, until teeth.

Week Twelve

TEETH!

1.Pork shoulder (puréed? Or make a pork-based demi-glace?)

2.Vegetable spaghetti squash. What kid wouldn’t love this? It’ll blow her mind! (How lucky she is to be teething by the start of squash season!)

3.Osso buco (get veal shanks from Al Norgaard at Hackenmuller’s).

Week Sixteen

TIME FOR GUILTY PLEASURES!

1 small package wild rice

2 cups cooked chicken (diced)

1 can cream of mushroom soup

½ can milk

Salt and pepper

¼ cup green pepper, chopped

Heat the oven to 350°F. Cook the rice according to the directions. Mix the rice, chicken, cream of mushroom soup, milk, salt and pepper, and green pepper. Place in a greased 2-quart casserole pan. Bake for 30 minutes.

2 cups sugar (maybe use less)

1½ cups salad oil (find substitute)

4 eggs

2 cups flour

2 teaspoons baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

3 teaspoons cinnamon

3 cups shredded carrots

1 cup chopped nuts (nut allergy risk?)

1 teaspoon vanilla

Heat the oven to 325°F. Combine the sugar, salad oil, eggs, flour, baking soda, salt, cinnamon, carrots, nuts, and vanilla and pour into a 9-by-13-inch pan. Bake for 45 minutes.

Icing recipe:

¼ pound or ½ cup butter (Grade AA)

8-ounce package cream cheese

3½ cups powdered sugar

Mix and spread on the cooled carrot cake.

This meal plan seemed like a sound strategy to Lars, who remained mindful of what was in season and what had sustained his own family through the long winters in Duluth. His main worry was the chopped nuts in the carrot cake recipe. He’d heard somewhere that a child could get a nut allergy from eating nuts too soon. But how soon was too soon? He had to talk to their obstetrician, Dr. Latch, who had a thick mustache, kind eyes, and what Lars interpreted as a can-do attitude.

In his office, Dr. Latch listened to Lars’s question and then looked at the young man the way someone might regard a toddler who’s holding a Buck knife.

“You want to feed carrot cake to a four-month-old?” Dr. Latch asked.

“Not a lot of carrot cake,” Lars said. “I mean, a small portion. A baby portion. I’m just concerned about the nuts in the recipe. I mean, I guess I could make it without nuts. But my mom always made it with nuts. What do you think?”

“Eighteen months. At the earliest. Probably wait until age two to be safe.”

“I could be wrong, but I remember my younger siblings eating carrot cake really young. There’s a picture of my brother Jarl on the day he turned one. They gave him a little carrot cake and he smeared it in his hair.”

“That’s the best outcome in that situation, probably.”

“Well, now he’s bald.”

“Looking over your dietary plan here, I’d have more immediate reservations.”

“Like what?”

“Well, pork shoulder to a three-month-old baby. Not advisable.”

“Puréed, maybe?” Lars asked. “I could braise it first. Or maybe just roast the bones and make pork stock for a demi-glace. That wouldn’t be my first choice, though.”

“You work at Hutmacher’s, right?” Dr. Latch said. “You do make an excellent pork shoulder. But give it at least two years.”

“Two years, huh?” He didn’t want to tell Dr. Latch that this conversation crushed his heart, but the doctor seemed to perceive this.

“I understand your eagerness to share your life’s passion with your first child. I see different versions of this all the time. The time will come. For now, just breast milk and formula for the first three months.”

“That’s awful,” Lars said.

“Maybe for you,” Dr. Latch said. “But your daughter is going to be monstrously satisfied with this diet. Trust me. Now, I’m going to refer you to the most vigilant pediatrician I know.”

• • •

Back at their apartment in St. Paul, lugging all of the unfamiliar baby gear out of their car, Lars was grateful they could afford a place with an elevator. While waiting for the doors to open, he saw the building’s lightly used concrete stairway, which he’d climbed a few times over the years for exercise. Feeling the straps of a diaper bag dig into his shoulder and the plastic handle of the portable baby seat against his palm, he guessed he might never use it again.

• • •

When they weren’t sleeping, trying to sleep, or holding their newborn daughter, Lars and Cynthia were usually in the kitchen. Lars didn’t want to take his eyes off of his beautiful girl for a minute, so he kept her strapped in the baby seat on the counter.

“Don’t you think it might be dangerous to have her in here?” Cynthia asked him the second night, while chopping garlic and parsley for an Alfredo sauce.

“That doctor can take away her right to eat,” Lars said. “But she should still be around the smells. Next best thing, you know.”

“Yeah. Smelling a bunch of food she can’t eat. It’s probably frustrating the hell out of her.”

“Well, this is where we are, and I want her with us.”

“I don’t know, putting a baby in a room full of knives and boiling water.”

“Where would you like her to be?”

Cynthia shook her head. “Somewhere else.”

Lars turned and looked at Eva, who was wearing a pink stocking cap for warmth, and mittens so she wouldn’t scratch her own face with her tiny fingernails. He didn’t ever intend to stare at her for such long stretches; it would just happen. When their eyes met, bam, there went five minutes. Or twenty.

Cynthia tapped him on the shoulder.

“Water’s ready for the pasta.”

“Where’s the fettuccine?” he asked her, opening the fridge.

She took a green Creamette box out from the lazy Susan by his feet. “I figured we’d try this brand. It was on sale.”

“I remember when we used to make our own pasta. I guess those days are over.”

“Thank God,” Cynthia said. “What a pain in the ass.”

• • •

Cynthia was still twenty-five, and bounced back to her skinny frame with color in her cheeks and bigger boobs, while Lars just grew balder and fatter and slower. He had learned, before she was pregnant, that he had to hold her hand or touch her in some way while they walked places together, so that other men knew they were a couple. Now that she was the mother of his daughter, he was even more wary, snarling at passing dudes with confident Tom Selleck mustaches and cool Bon Jovi hair. Cynthia, pushing a stroller as they perused the winter farmers’ markets, didn’t mind Lars’s hulking shadow or the expressions he’d snap at ogling perverts; she was mostly just happy that she could drink again.

• • •

“They’re looking for a new sommelier at Hutmacher’s,” Cynthia said one morning, while Lars was changing Eva’s diaper. Cynthia’s sensitive nose couldn’t handle the smell of her daughter’s poop, but for Lars, after a decade of making lutefisk, it was easier than flipping an omelet.

“It’s only been a month,” Lars said. “They said you could have three.”

“They said I could come back after three. It’s not like they’re paying me maternity leave.”

“Then take the full three. We have savings.” This was not true, after the hospital bills, but Lars didn’t want Cynthia to worry about all that.

“I know, but I’m going batshit here. It’s the middle of summer and I can’t do anything useful outside with that kid strapped on me. And I can’t stand what’s on TV in the afternoons. And I can’t get more than twenty pages through a book before she starts wailing.”

“So you want to go back to work early?”

“I’ve been thinking about it, and I bet we can work out a schedule so that one of us is always home. And Jarl and Fiona are around if we need them.”

Lars’s younger brother and his girlfriend also lived in St. Paul, a few miles away, and were eager to babysit their niece, but Lars had privately hoped that his baby girl would never be away from both of her parents simultaneously except in an absolute emergency. “Don’t you have to take a course or something to be a sommelier?”

“I know the restaurant and its customers better than anyone they could bring in. I also know that wine list back to front. I even picked out a few. The Tepusquet Vineyard Chardonnay from ZD Wines—that was mine.”

“I don’t know,” Lars said. He realized that if he was meeting her that day for the first time, he would’ve told her to go for it, pursue her dreams, all that kind of stuff. But now, looking at his beautiful, impulsive wife, he thought of his stoic, pragmatic mother. If Elin had ever wanted to be anything besides an unpaid bookkeeper at a bakery and a mother to three boys, Lars sure never heard a peep about it. Was it selfish or realistic to look at Cynthia and want the same, to want to look on in admiration as her arms, legs, hips, and devotion thickened? He didn’t know.

“I think you don’t want me to do anything with my life besides be a mom. Well, that’s bullshit,” Cynthia said, and she left the room.

It would be bullshit if it were true, and it partly was. Yes, he just wanted her to want to be a mom, in the same way that he felt, with all of his blood, that he was a dad first, and everything else in the world an obscure, unfathomably distant second.

• • •

Lars was lying on the brown shag area rug, reading to his daughter from James Beard’s Beard on Bread, when Cynthia pushed open the front door. Lars could tell how her meeting had gone from her heavy footsteps. Instead of Cynthia, the restaurant had hired “the famous and respected West Coast sommelier Jeremy St. George” and offered her a job as “supervising floor waitress,” which wasn’t even a real job, just something they’d made up on the spot to appease her when she started making a scene.

• • •

Cynthia was so furious that evening, she opened a single-vineyard Merlot from Stag’s Leap that she’d been saving, and paired it with a bowl of macaroni and cheese from a box.

“Why did he move out here from San Francisco to take this job?” she asked Lars, as if he knew. “He could have any sommelier job in the country!”

She told him that the manager had shown her Jeremy St. George’s résumé and headshot, because all of the big California sommeliers had headshots that made them appear both studious and sensual. Cynthia said he was in his early thirties, a graduate of UC Davis, formerly a sommelier in Napa Valley and San Francisco, and he looked like an underwear model. Lars wondered for a moment why she had to say “underwear” and not just “model.”

Still, what concerned Lars more was the box of macaroni and cheese. It had been a pretty darn brisk slide from their first store-bought pasta to their first processed dairy, and he had to admit that their financial situation was mostly to blame. They were living on just his income, and while everyone outside the restaurant industry seemed to think that being a chef at a nice place was a path to riches, it sure wasn’t the case. Even with his working fifty hours a week as a chef at Hutmacher’s, there were going to be tight months ahead.

He hated to admit it, but if they wanted to eat better and have fresher, more nutritious food around the house for their daughter—who was finally old enough to be eating mushy fruit and vegetables—Cynthia had to go back to work.

• • •

Lars proposed that she demand part-time sommelier duties if she returned, and although Cynthia chafed against the idea of being some West Coast hotshot’s “assistant,” she admitted that having a job title, any job title, with the word “sommelier” in it could make returning to Hutmacher’s more bearable.

The owners of Hutmacher’s agreed to the new assistant sommelier title and the job duties, just so long as she also picked up waitress shifts and Jeremy St. George approved of the whole thing. Jeremy St. George said he’d have to meet her first, and after they met, Jeremy told Cynthia that he’d been waiting for an assistant like her all of his life.

The night of her first shift, she came home late, ninety minutes after close, careening through the doorway, singing a Replacements song. He hadn’t heard her sing in maybe a year. “How was it?” Lars asked, but he could tell.

At the end of the night, she turned to him and said, “Thank you,” before passing out on her side of the bed. Her face, even while asleep, was full of love, and Lars chose to be reassured.

• • •

With Cynthia out of town on wine trips as part of her new job, Lars’s rounds at the St. Paul Farmers’ Market were more logistically difficult, but still just as fun. For some individuals, the process of carrying a two-month-old infant, her diaper bag, and her stroller everywhere could be tiring and complex, but it actually made Lars feel invigorated, even when he had to do it all by himself. With Jarl and Fiona now officially on babysitting detail during the hours that Lars’s and Cynthia’s shifts overlapped, Lars wanted to make the most of every minute with his daughter.

The late summer heat flooded his body as soon as he stepped outside; armpit stains blossomed in his Fruit of the Loom T-shirt while he was still in the elevator, and he was wheezing by the time he got Eva and her stuff down to the car. But the St. Paul Farmers’ Market would, as always, reward their efforts. Mid-September meant the end of peak season for late-harvest tomatoes, and Lars had plans for more chilled soups, sauces, and mild salsas that he knew Eva’s young palate would just adore, based on how much she loved the tragically few things that Dr. Latch let him feed her so far.

He’d never realized how couples dominated the farmers’ market scene until his wife started going out of town. Saturday morning pairs meandered playfully through the aisles of apples, beets, and lettuces, many with strollers or children in hand. Some were childless, flush from the impulse buy of true love and its heady aftershocks, hands still lingering on each other, as if to make sure the other person was still real. Lars tried to remember what that felt like, but the people stopping to adore his baby daughter distracted him from dwelling on the lone missing member of their little family.

• • •

“Do you know that half a cup of marinara sauce has almost eight times the lycopene content of a raw tomato?” he asked his wiggly daughter as he guided her through the slow field of couples that ebbed and pushed around them. “We’re going to find some good sauce tomatoes today.”

Eva looked up at him, pinching her eyelids against the bright sky, but making happy eye contact with him that seemed to say, I love Dad, or maybe, I just took the runniest shit my father will ever see. In direct sunlight, it was hard to tell.

• • •

Karen Theis’s tomato stall, which for close to a decade had supplied the five-county metro area with consistent, handsome Roma, plum, beefsteak, and Big Boy tomatoes—nothing fancy, just the major hybrids—was Lars’s first and only tomato stop. But that morning in September, it was gone, and in its place a heavy man and heavier woman sat on purple beach chairs, selling dirt-streaked, unappealing rhubarb (it was way, way past ideal rhubarb season) from a stained cardboard box.

“Oh. What happened to Karen?” Lars asked the hefty woman.

She stared back at him. “Who’s Karen?”

“Want some rhubarb?” the big guy asked. “We’ll bargain with ya.” Flies were landing on the sugary stalks, rubbing their front legs together. The couple made no attempt to shoo them away.

“Karen ran a tomato stall here for the last eight years, right in this location. Just wondering what happened to her, if she moved or is just on vacation or something.”

“Oh yeah, that name sounds familiar,” the guy asked, and then turned to the woman. “Why does that name sound familiar?”

“People have been asking about her all morning.”

The guy nodded. “That’s where I know it from.”

This kind of exchange was to be expected of people who attempt to sell rhubarb in mid-September. “So, what happened to her?” Lars asked again.

The woman looked at Eva in the stroller. “Well, that’s a cutie. How old is your daughter, one?”

“She’s about three and a half months. She’s big for her age. So you have no idea what happened to Karen’s tomato stall?”

As the guy leaned forward in his chair, Lars noticed that one of the armrests was missing, and the man had a series of bright red circles on his left forearm from leaning it against the exposed pole. “Sir, if I know one thing,” the man said, “it’s never call a woman fat. Especially at that young age where it seeps into their unconscious.”

“Can anyone help me find Karen Theis?” Lars shouted, looking around at the nearby vendors.

“Out of business,” a nearby vendor of Nantes-type carrots said. “The Orientals chased her out.”

Anna Hlavek, the herb vendor one stall over, yelled, “The Orientals didn’t chase her out, the Orientals grow better tomatoes.”

Lars met Anna’s gaze, and it apparently gave her license to continue her argument.

“What’s-his-name Oriental fella over there. That’s where the New French Café gets their tomatoes now, y’know,” Anna said, referring to the trendiest of the new Minneapolis restaurants. “How’s your little girl?” she asked, stepping out from behind her stand to touch Eva’s hands and lift them in the air. “Sooooo big! Soooo big!”

Lars liked Anna, but people touching his daughter without asking him first got his blood up a little bit.

“Tell me again,” Anna said. “Is she one, one and a half?”

“No, three and a half months. She’s just . . . ambitious for her age.”

“Where’s that cute wife of yours? Still in California?”

“Yep,” Lars said. “It’s harvest time, for certain varietals.”

“Oh boy, how long is that going to take her?”

“Two weeks, I think.” It had been four already, but Lars knew that sounded bad.

“I can’t imagine a mother being away from her child for that long. My Dougie goes everywhere with me. I never let him out of my sight for a minute.” Lars saw a sullen, towheaded four-year-old sitting a few feet away, stabbing pavement cracks with a plastic knife.

“It happens in the wine business,” he said. “So where can I find a few tomatoes?”

• • •

The Southeast Asian vendor sat on a blue Land O’ Lakes milk crate, his body broad and oblong like an Agassiz potato, his fat tan legs splayed. He stared ahead—unsmiling, through Ray-Ban sunglasses—at everything, or nothing. Beside him, shimmering in the livid heat, sat platoons of beautiful, alien tomatoes, in heartbreakingly bright orange, red, yellow, purple, and stripes, in precise, labeled grids across a trestle table covered with a clean gingham tablecloth.

• • •

As Lars pushed his daughter’s stroller toward the stand, Eva reached in the direction of the tomatoes, her chubby fingers grabbing the air between herself and those brilliant little globes.

“Hi. Do you have samples?” Lars asked the vendor.

“No samples,” the man said, not taking his gaze from Eva’s outstretched hands. “You try, you buy.”

“Maybe I will, then,” Lars said. “I’m looking for a sauce tomato, something high in lycopene, like a Roma VF. What do you sell that’s like a Roma VF?”

“I don’t sell anything like a Roma VF. I sell tomatoes.”

“OK. So what’s a Roma VF, then?”

“Made in a lab by scientists.”

“OK.”

“Sir, if you want a lycopene-rich tomato, you want a Moonglow. Highest amount of lycopene. Of any heirloom.”

The vendor picked up a small orange globe, between a golf ball and a baseball in diameter, and showed it to Lars, not handing it to him. Lars reached for it, and the vendor set it back with its sisters again.

“The Moonglow is for slicing and salsas,” the vendor continued. “If you want a sauce tomato, you want San Marzano. Best in the world for paste and sauce.” He held up a long red tomato shaped a little like a red pepper and gently laid it in his own palm.

“I’ll buy a Moonglow, to try it.”

“Thirty cents,” the vendor said.

“Well dang,” Lars said. “At that price, it would cost me two bucks to make anything.”

“Cheaper by the pound. Individually, thirty cents.”

Lars sighed, but then exchanged a pair of gray coins for a soft, gleaming orange ball. He just had to. He bit into it like an apple, and orange water flung across his mouth and stuck to his beard. The sensation bothered him just for a moment before the flavor of the heirloom broke across his palate.

The approach was wonderfully sweet, but not sugary or overpowering; there was just a whisper of citric tartness. As he chewed the Moonglow’s firm flesh, he closed his eyes to concentrate on the vanishing sweetness in his mouth. He thought of Cynthia and how the last time they were here, they bought Roma VFs for a dish to pair with a light-bodied Corvina Veronese. He thought about how much she’d love this—how she’d be coming up with wine pairings for each of this guy’s tomatoes—and wondered where she was in California right then. He thought about how this trip had been the longest yet and how it had been three days since he’d heard from her.

• • •

Lars shook himself from these thoughts and knelt to hold the other half of the Moonglow to Eva’s mouth. Grinning, she smeared its bright carcass across her radiant face.

He introduced himself to the vendor, told him what he did, and asked the man his name.

“John,” the vendor said, not smiling, shaking hands firmly but briefly.

“Best thirty cents I’ve ever spent in my life, John,” Lars said. “I had no idea that the Hmong grew such brilliant tomatoes.”

“They don’t. But if they’re lucky, maybe I’ll teach one of them how.”

“Oh jeez, I suppose I thought you were Hmong.”

“Christ, you people. I’m Lao, from Laos. Big difference. The Hmong, we let them in from Mongolia. Never should’ve done it. They were trouble from the beginning. Their Plain of Jars? Lot of poppy fields up there. I don’t have to tell you what they kept in those jars. It wasn’t water.”

Lars was taught always to listen politely, but the prejudices of this heirloom tomato grower—a sharply opinionated lot regardless of national origin—began to make him feel a tad uncomfortable. Because of this, his awareness clouded, and he only saw Eva out of the corner of his eye as she grabbed the corner of the tablecloth and pulled her way over to the tomatoes. The soft thud of massive amounts of fruit hitting the ground was unmistakable to anyone who’s ever worked with food.

“Oh crap!” Lars said, taking in the pile of tomatoes on the ground. “Oh crap, oh crap, oh crap.”

John pushed past Lars with the decisive force of a first responder at the scene of an accident, and knelt over his tomatoes, unsentimentally sorting the resellable from the irretrievably broken.

When Lars pushed the tomatoes aside from his daughter’s face, he was shocked to find that she wasn’t crying, but rather trying to cram a broken Moonglow into her tiny mouth.

While Lars and John were able to save most of the San Marzanos, about half of the Moonglows and almost all of the pink Brandywines were bruised or splattered from their impact with the ground, the stroller, or baby Eva.

“How much do I owe you?” Lars asked, afraid even to look John in the face.

“Accidents happen,” he said. He put the broken fruit in a box under the tablecloth and sat back on his milk crate.

Lars removed a twenty and a ten from his billfold and held them out to John. It hurt him to do it; it was almost half a day’s wages.

“Here,” he said. “Please take it.”

The vendor didn’t speak or acknowledge the cash. As passersby and other vendors stared at him, Lars’s face burned with shame. After fighting through several seconds of silence, he had to put the bills away and understand that the depths of this debt might occupy a different space than money could fill.

• • •

On the fourth day without hearing from Cynthia, Lars started to call around. Their manager, Mike Reisner, had heard nothing, and neither of the owners, Nick Argyros or Paul Hinckley, had heard from either Cynthia or Jeremy. By the afternoon, he was calling wineries he knew they might have visited: Stag’s Leap, Cakebread, Shafer, Ridge, Stony Hill, Silver Oak. He even tried a few of the Rhone Rangers, like Bonny Doon and Zaca Mesa; they all knew Jeremy St. George, but no one had seen him or Cynthia.

“Are you sure?” he asked the guy at Shafer. “They’d be there for the harvest.”

“Our harvest isn’t for several weeks,” the guy said.

Lars’s brother Jarl didn’t seem alarmed. “They’re probably driving back,” he said, lying on Lars’s shag carpet, still wearing the white dress shirt and tie from his job as a paralegal. Once Jarl had left the tyranny of their father’s empire, he’d wanted a job that required him to wear a tie every day; in Jarl’s world, people wearing ties would never have to make lutefisk or stick their hands in a hot oven or lift pallets of pullman loaves or otherwise suffer physically on the clock.

“But they flew out there,” Lars reminded him.

“Aren’t there wineries in Arizona and Texas, and places like that?”

“None of the big places in Napa saw them,” Lars said from his easy chair. Eva was on his lap, sucking on the end of a turkey baster.

“Maybe they didn’t go to the big places,” Jarl said. “Or maybe they’re somewhere good, like Riunite.”

“Riunite’s not a place.”

“Yeah it is. It’s in here,” Jarl said, pointing to his heart. “Get over yourself and like something that normal people like for once.”

“I like normal things. I just also like quality healthy things.”

“I like quality healthy things sometimes,” Jarl said.

This was not true. For a guy who insisted on dressing nicely all of the time, Jarl had terrifyingly provincial taste in food and wine.

“You, I haven’t even seen you eat a vegetable since the early eighties.”

Jarl seemed surprised. “Where was that?”

“And it hardly counts. The coleslaw at Charlie’s Café Exceptionale.”

“That was the best place in town. Not someplace snooty like Faegre’s.”

Lars shook his head. “Best Caesar I’ve ever had.”

“Christ, you’re a snob,” Jarl said, and looked at Eva. “Admit it. And you’re going to raise her to be a snob, too. She’s going to be the biggest snob of all time. Between the two of you, the fancy food chef and the fancy wine drinker. Next time I babysit her, I’m feeding her Cheetos.”

“Don’t even think about it.”

“Cheetos and Hi-C.”

“Please, don’t.”

“We ate that kind of stuff as kids. What’s your problem with it now?”

“I just want my children eating stuff that’s actually nutritious.”

“Children?” Jarl asked. “Got some news?”

“Yes, we’re having another kid.”

“When? I thought you guys were going to wait five years or something.”

“No, last time I talked to Cynthia, I told her I want another one now. I don’t want to be a fat old man chasing around a toddler.”

“Then lose some weight, lardo,” Jarl said.

Lars’s phone rang.

“Can you get it?” Lars said, pointing to the baby on his lap.

“Oh sure,” Jarl said. He did four push-ups, with a clap between each one, his tie hanging to the floor like a long striped tongue, and rose to pick up the receiver in the kitchen. “Hello, Thorvald residence,” he said.

“Who is it?” Lars asked.

“It’s your work. Paul somebody.”

“One of the owners,” Lars said, setting his daughter on the carpet before running into the kitchen. “Keep an eye on Evie,” he told Jarl as he put the phone to his ear.

• • •

“Hey there, Lars,” Paul Hinckley said. He’d previously been a big-time lawyer in the Cities, and he didn’t know much about food, but he was more than a tad detail-oriented as a restaurant owner. He didn’t hire a graphic designer or an interior decorator for anything; he chose the logo, the typeface on the menu, the dining room’s color scheme, the design of the flatware and stemware, and even the names of some of the dishes. He also liked to know what was going on with everyone on his staff all the time.

“Hello, Paul. What’s happening?”

“Well, hi, Lars. Say, just have a quick bit of news for ya here.”

“Sure, what’s going on?”

“Just wanted to tell you, we had a staff parking space open up, and we thought maybe you’d want it—you know, for all the hard work you’ve done for us.”

“Yeah, sure, it’d be nice to park on the property there.”

“That’s what we were thinking—you know, me and Nick. We thought, who deserves it? And your name came right up, so.”

“So yeah, is that it, then?”

“Yeah, pretty much, I guess. But I thought, maybe you’d want to know, the reason the spot opened up is because Jeremy St. George tendered his resignation today, effective immediately. So, you can have his spot when you come in this afternoon already.”

“You heard from Jeremy St. George?”

“Yep, he called us from the airport, and said he was quitting, so.”

“What did he say about Cynthia? Did he say anything about Cynthia? She’s with him, you know.”

“Oh, I figured she talked to you. Well, we asked, we did ask, and he said that she had her own decision to make, so I guess we’ll see. We’ll see on that. Oh, I got a call on the other line. Can you hold, please?”

“No, that’s all right,” Lars said. He hung up the phone and stared out into the living room at his daughter, who was lying on her back, sucking on an egg separator, as her uncle tried to make her smile.

• • •

Three days later, Lars opened his lobby mailbox to a letter, postmarked San Francisco. He saw the swoops and curls of the hand behind the blue pen that had written their address, and he tore open the envelope right there.

My Dear Lars,

I don’t know how to say this. I suppose I should’ve called, but every time I picked up the phone and started to dial our number, I started to cry. Plus I knew you would try to talk me out of this, and at this point, you can’t. Since I last saw you five weeks ago, I’ve had experiences and made choices that would make it impossible for me to return to you with a whole heart. You could argue for me to come back, but the person you want no longer exists, and maybe never did.

You are the best father the world has ever seen. But I wasn’t cut out to be a mother. The work of being a mom feels like prison to me. I know this might sound horribly selfish to you, but out here in California, I found a sense of happiness that I haven’t felt since before I was pregnant. If you truly want me to be happy, you must try to understand this. I will never be happy being a mother. Having a child was the biggest mistake of my life and I honestly believe that our daughter will be better off having no mother instead of a bad one.

I’m leaving today for Australia or New Zealand. I haven’t decided which yet, but by the time you read this, I’ll be in that part of the world. You’re free to keep, give away, or throw away anything of mine I’ve left behind. Don’t try to send anything to me and please don’t come looking for me.

A lawyer will be serving you with divorce papers. I’m giving you full custody of our child and complete ownership of our shared property. Please sign it as written. Otherwise, it will only lengthen the process, because I will not return to the U.S. for any reason, perhaps for a very long time.

Maybe it won’t seem like it to you, but the reason I have to make such a clean break is because this is absolutely heartbreaking to me. I love you so much and I will think of you every day for the rest of my life. You have made me a better person, a person brave enough to know what she is and what she is not.

I am so sorry to put you through this. I didn’t mean to lose you. But you are just so passionate about being a father, I feel that the kindest thing I can do is to free you from our marriage so you can find a woman who’s equally committed to being a mother. I know she’s out there for you. You’re an incredible guy, the kindest man I’ve ever met, and any woman would be lucky to have you. I want you to actually have the life, and the family, you thought you had with me. If I come back to you, you will not have that.

I have to go. I will miss you so, so much.

All my love, forever,

Cynthia

• • •

Lars unlocked the front door of his quiet apartment. He’d intended to just leave Eva alone for a moment while he checked the mail. She was still sleeping on a blanket in the middle of the living room floor, as if he’d never left, and what he’d found in the mailbox never existed. He walked the letter into the kitchen, softly opening a child-locked drawer under the counter. His daughter should never see this letter or know the words inside it, he decided, so he would burn it, right now, in the sink, but now he couldn’t find his butane BBQ lighter. Or even his crème brûlée torch. He wanted to burn the letter now, so that maybe all of the bad thoughts would be burned along with it.

He heard his daughter stir and start to cry. He ignited a gas burner on his stove and held the letter to the flame. It caught fire so fast that he dropped it on the kitchen floor and watched it whisper out on the brown vinyl.

His daughter started to wail.

Kitchens of the Great Midwest

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- ISBN-10: 0143109413

- ISBN-13: 9780143109419