Excerpt

Excerpt

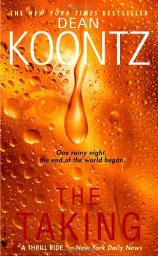

The Taking

1

A few minutes past one o'clock in the morning, a hard rain fell

without warning. No thunder preceded the deluge, no wind.

The abruptness and the ferocity of the downpour had the urgent

quality of a perilous storm in a dream.

Lying in bed beside her husband, Molly Sloan had been restless

before the sudden cloudburst. She grew increasingly fidgety as she

listened to the rush of rain.

The voices of the tempest were legion, like an angry crowd chanting

in a lost language. Torrents pounded and pried at the cedar siding,

at the shingles, as if seeking entrance.

September in southern California had always before been a dry month

in a long season of predictable drought. Rain rarely fell after

March, seldom before December.

In wet months, the rataplan of raindrops on the roof had sometimes

served as a reliable remedy for insomnia. This night, however, the

liquid rhythms failed to lull her into slumber, and not just

because they were out of season.

For Molly, sleeplessness had too often in recent years been the

price of thwarted ambition. Scorned by the sandman, she stared at

the dark bedroom ceiling, brooding about what might have been,

yearning for what might never be.

By the age of twenty-eight, she had published four novels. All were

well received by reviewers, but none sold in sufficient numbers to

make her famous or even to guarantee that she would find an eager

publisher for the next.

Her mother, Thalia, a writer of luminous prose, had been in the

early years of an acclaimed career when she died of cancer at

thirty. Now, sixteen years later, Thalia's books were out of print,

her mark upon the world all but erased.

Molly lived with a quiet dread of following her mother into

obscurity. She didn't suffer from an inordinate fear of death;

rather, she was troubled by the thought of dying before achieving

any lasting accomplishment.

Beside her, Neil snored softly, oblivious of the storm.

Sleep always found him within a minute of the moment when he put

his head on the pillow and closed his eyes. He seldom stirred

during the night; after eight hours, he woke in the same position

in which he had gone to sleep--rested, invigorated.

Neil claimed that only the innocent enjoyed such perfect

sleep.

Molly called it the sleep of the slacker.

Throughout their seven years of marriage, they had conducted their

lives by different clocks.

She dwelled as much in the future as in the present, envisioning

where she wished to go, relentlessly mapping the path that ought to

lead to her high goals. Her strong mainspring was wound

tight.

Neil lived in the moment. To him, the far future was next week, and

he trusted time to take him there whether or not he planned the

journey.

They were as different as mice and moonbeams.

Considering their contrasting natures, they shared a love that

seemed unlikely. Yet love was the cord that bound them together,

the sinewy fiber that gave them strength to weather disappointment,

even tragedy.

During Molly's spells of insomnia, Neil's rhythmic snoring,

although not loud, sometimes tested love almost as much as

infidelity might have done. Now the sudden crash of pummeling rain

masked the noise that he made, giving Molly a new target upon which

to focus her frustration.

The roar of the storm escalated until they seemed to be inside the

rumbling machinery that powered the universe.

Shortly after two o'clock, without switching on a light, Molly got

out of bed. At a window that was protected from the rain by the

overhanging roof, she looked through her ghostly reflection, into a

windless monsoon.

Their house stood high in the San Bernardino Mountains, embraced by

sugar pines, knobcone pines, and towering ponderosas with dramatic

fissured bark.

Most of their neighbors were in bed at this hour. Through the

shrouding trees and the incessant downpour, only a single cluster

of lights could be seen on these slopes above Black Lake.

The Corrigan place. Harry Corrigan had lost Calista, his wife of

thirty-five years, back in June.

During a weekend visit to her sister, Nancy, in Redondo Beach,

Calista parked her Honda near an ATM to withdraw two hundred

dollars. She'd been robbed, then shot in the face.

Subsequently, Nancy had been pulled from the car and shot twice.

She had also been run over when the two gunmen escaped in the

Honda. Now, three months after Calista's funeral, Nancy remained in

a coma.

While Molly yearned for sleep, Harry Corrigan strove every night to

avoid it. He said his dreams were killing him.

In the tides of the storm, the luminous windows of Harry's house

seemed like the running lights of a distant vessel on a rolling

sea: one of those fabled ghost ships, abandoned by passengers and

crew, yet with lifeboats still secured. Untouched dinners would be

found on plates in the crew's mess. In the wheelhouse, the

captain's favorite pipe, warm with smoldering tobacco, would await

discovery on the chart table.

Molly's imagination had been engaged; she couldn't easily shift

into neutral again. Sometimes, in the throes of insomnia, she

tossed and turned into the arms of literary inspiration.

Downstairs, in her study, were five chapters of her new novel,

which needed to be polished. A few hours of work on the manuscript

might soothe her nerves enough to allow sleep.

Her robe draped the back of a nearby chair. She shrugged into it

and knotted the belt.

Crossing to the door, she realized that she was navigating with

surprising ease, considering the absence of lamplight. Her sureness

in the gloom couldn't be explained entirely by the fact that she

had been awake for hours, staring at the ceiling with dark-adapted

eyes.

The faint light at the windows, sufficient to dilute the bedroom

darkness, could not have traveled all the way from Harry Corrigan's

house, three doors to the south. The true source at first eluded

her.

Storm clouds hid the moon.

Outside, the landscape lights were off; the porch lights,

too.

Returning to the window, she puzzled over the tinseled glimmer of

the rain. A curious wet sheen made the bristling boughs of the

nearest pines more visible than they should have been.

Ice? No. Stitching through the night, needles of sleet would have

made a more brittle sound than the susurrant drumming of this

autumn downpour.

She pressed fingertips to the windowpane. The glass was cool but

not cold.

When reflecting ambient light, falling rain sometimes acquires a

silvery cast. In this instance, however, no ambient light

existed.

The rain itself appeared to be faintly luminescent, each drop a

light-emitting crystal. The night was simultaneously veiled and

revealed by skeins of vaguely fluorescent beads.

When Molly stepped out of the bedroom, into the upstairs hall, the

soft glow from two domed skylights bleached the gloom from black to

gray, revealing the way to the stairs. Overhead, the rainwater

sheeting down the curved Plexiglas was enlivened by radiant whorls

that resembled spiral nebulae wheeling across the vault of a

planetarium.

She descended the stairs and proceeded to the kitchen by the

guidance of the curiously storm-lit windows.

Some nights, embracing rather than resisting insomnia, she brewed a

pot of coffee to take to her desk in the study. Thus stoked, she

wrote jagged, caffeine-sharpened prose with the realistic tone of

police-interrogation transcripts.

This night, however, she intended to return eventually to bed.

After switching on the light in the vent hood above the cooktop,

she flavored a mug of milk with vanilla extract and cinnamon, then

heated it in the microwave.

In her study, volumes of her favorite poetry and prose--Louise

GlYck, Donald Justice, T. S. Eliot, Carson McCullers, Flannery

O'Connor, Dickens--lined the walls. Occasionally, she took comfort

and inspiration from a humble sense of kinship with these

writers.

Most of the time, however, she felt like a pretender. Worse, a

fraud.

Her mother had said that every good writer needed to be her own

toughest critic. Molly edited her work with both a red pen and a

metaphorical hatchet, leaving evidence of bloody suffering with the

former, reducing scenes to kindling with the latter.

More than once, Neil suggested that Thalia had never said--and had

not intended to imply--that worthwhile art could be carved from raw

language only with self-doubt as sharp as a chisel. To Thalia, her

work had also been her favorite form of play.

In a troubled culture where cream often settled on the bottom and

the palest milk rose to the top, Molly knew that she was short on

logic and long on superstition when she supposed that her hope for

success rested upon the amount of passion, pain, and polish that

she brought to her writing. Nevertheless, regarding her work, Molly

remained a Puritan, finding virtue in self-flagellation.

Leaving the lamps untouched, she switched on the computer but

didn't at once sit at her desk. Instead, as the screen brightened

and the signature music of the operating system welcomed her to a

late-night work session, she was once more drawn to a window by the

insistent rhythm of the rain.

Beyond the window lay the deep front porch. The railing and the

overhanging roof framed a dark panorama of serried pines, a

strangely luminous ghost forest out of a disturbing dream.

She could not look away. For reasons that she wasn't able to

articulate, the scene made her uneasy.

Nature has many lessons to teach a writer of fiction. One of these

is that nothing captures the imagination as quickly or as

completely as does spectacle.

Blizzards, floods, volcanos, hurricanes, earthquakes: They

fascinate because they nakedly reveal that Mother Nature, afflicted

with bipolar disorder, is as likely to snuff us as she is to succor

us. An alternately nurturing and destructive parent is the stuff of

gripping drama.

Silvery cascades leafed the bronze woods, burnishing bark and bough

with sterling highlights.

An unusual mineral content in the rain might have lent it this

slight phosphorescence.

Or . . . having come in from the west, through the soiled air above

Los Angeles and surrounding cities, perhaps the storm had washed

from the atmosphere a witch's brew of pollutants that in

combination gave rise to this pale, eerie radiance.

Sensing that neither explanation would prove correct, seeking a

third, Molly was startled by movement on the porch. She shifted

focus from the trees to the sheltered shadows immediately beyond

the glass.

Low, sinuous shapes moved under the window. They were so silent,

fluid, and mysterious that for a moment they seemed to be imagined:

formless expressions of primal fears.

Then one, three, five of them lifted their heads and turned their

yellow eyes to the window, regarding her inquisitively. They were

as real as Molly herself, though sharper of tooth.

The porch swarmed with wolves. Slinking out of the storm, up the

steps, onto the pegged-pine floor, they gathered under the shelter

of the roof, as though this were not a house but an ark that would

soon be set safely afloat by the rising waters of a cataclysmic

flood.

2

In these mountains, between the true desert to the east and the

plains to the west, wolves were long extinct. The visitation on the

porch had the otherworldly quality of an apparition.

When, on closer examination, Molly realized that these beasts were

coyotes--sometimes called prairie wolves--their behavior seemed no

less remarkable than when she had mistaken them for the larger

creatures of folklore and fairy tales.

As much as anything, their silence defined their strangeness. In

the thrill of the chase, running down their prey, coyotes often cry

with high excitement: a chilling ululation as eerie as the music of

a theremin. Now they neither cried nor barked, nor even

growled.

Unlike most wolves, coyotes will frequently hunt alone. When they

join in packs to stalk game, they do not run as close together as

do wolves.

Yet on the front porch, the individualism characteristic of their

species was not in evidence. They gathered flank-to-flank,

shoulder-to-shoulder, eeling among one another, no less communal

than domesticated hounds, nervous and seeking reassurance from one

another.

Noticing Molly at the study window, they neither shied from her nor

reacted aggressively. Their shining eyes, which in the past had

always impressed her as being cruel and bright with blood hunger,

now appeared to be as devoid of threat as the trusting eyes of any

household pet.

Indeed, each creature favored her with a compelling look as alien

to coyotes as anything she could imagine. Their expressions seemed

to be imploring.

This was so unlikely that she distrusted her perceptions. Yet she

thought that she detected a beseeching attitude not only in their

eyes but also in their posture and behavior.

She ought to have been frightened by this fanged congregation. Her

heart did beat faster than usual; however, the novelty of the

situation and a sense of the mysterious, rather than fear,

quickened her pulse.

The coyotes were obviously seeking shelter, although never

previously had Molly seen even one of them flee the tumult of a

storm for the protection of a human habitation. People were a far

greater danger to their kind than anything they might encounter in

nature.

Besides, this comparatively dark and quiet tempest had neither the

lightning nor the thunder to chase them from their dens. The

formidable volume of the downpour marked this as unusual weather;

but the rain had not been falling long enough to flood these stoic

predators out of their homes.

Although the coyotes regarded Molly with entreating glances, they

reserved the greater part of their attention for the storm. Tails

tucked, ears pricked, the wary beasts watched the silvery torrents

and the drenched forest with acute interest if not with outright

anxiety.

As still more of their wolfish kind slouched out of the night and

onto the porch, Molly searched the palisade of trees for the cause

of their concern.

She saw nothing more than she had seen before: the faintly radiant

cataracts wrung from a supersaturated sky, the trees and other

vegetation bowed and trembled and silvered by the fiercely

pummeling rain.

Nonetheless, as she scanned the night woods, the nape of her neck

prickled as though a ghost lover had pressed his ectoplasmic lips

against her skin. A shudder of inexplicable misgiving passed

through her.

Rattled by the conviction that something in the forest returned her

scrutiny from behind the wet veil of the storm, Molly backed away

from the window.

The computer monitor suddenly seemed too bright--and revealing. She

switched off the machine.

Black and argentine, the mercurial gloom streamed and glimmered

past the windows. Even here in the house, the air felt thick and

damp.

The phosphoric light of the storm cast shimmering reflections on a

collection of porcelains, on glass paperweights, on the white-gold

leafing of several picture frames. . . . The study had the

deep-fathom ambience of an oceanic trench forever beyond the reach

of the sun but dimly revealed by radiant anemones and luminous

jellyfish.

Excerpted from THE TAKING © Copyright 2004 by Dean Koontz.

Reprinted with permission by Bantam, a division of Random House

Inc. All rights reserved.