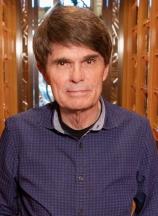

Interview: January 7, 2011

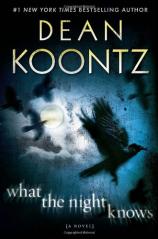

Dean Koontz is the international bestselling author of over 80 heart-stopping masterpieces, including WHAT THE NIGHT KNOWS, a chilling tale about a homicide detective’s relentless quest to put the killer who murdered his family to rest once and for all --- before his wife and children become the next victims. In this interview with Bookreporter.com’s Sarah Rachel Egelman, Koontz discusses the dream that inspired his latest novel, elaborating on the eerie figure that evolved into Alton Turner Blackwood and why this particular character has haunted him the most. He also muses on the questions of good and evil that found their way into the book, shares some of his favorite ghost stories, and reveals what’s next for a couple of his spine-tingling series.

Bookreporter.com: What was the seed or inspiration for WHAT THE NIGHT KNOWS? Did you have the characters or the general plot first?

Dean Koontz: The origin of this one was different in that it started with the deformed killer, Alton Turner Blackwood, after I saw him in a 3-D Benedryl dream. My allergies were in high gear, and for a couple of weeks I was taking half a dozen Benedryl a day, maybe more. When I take Benedryl for a while, I have dreams like no others. In fact, I generally don't dream unless I take Benedryl. These dreams don't have story lines. They don't have any momentum at all. They tend to be static encounters with exceedingly vivid and highly detailed people. The people never say anything. They stare at me for what seems like 10 or 20 minutes, and they are not merely as detailed as people in real life but hyper-real, extraordinarily detailed, and there is no vague, dreamlike quality whatsoever.

Sometimes they seem innocent, only curious about me. But others have a quality of extreme menace. These aren't nightmares in the classic sense, because the threat is perceived but never manifested. Prior to the Blackwood figure, none of these Benedryl people have ever been monstrous in appearance, just very intense and present. Blackwood was the first --- and so far the last --- to be deformed, obviously demented. And I saw him in three different dreams on successive nights. He is also the only figure in a Benedryl dream to appear more than once.

He didn't have a name, of course. He was just this strange creature, and I kept thinking about him during the day. I wondered what his past must be, where he came from, what accounted for his exceedingly disturbing appearance. The first thing I wrote was the initial entry in Blackwood's journal, which eventually I inserted between Chapters 8 and 9. His eerie voice flowed as if he were dictating the journal to me, and suddenly I knew that he was a murderer of entire families and that, though he had been killed long in the past, death would not stop him. It would be a ghost story.

The Calvino family --- Blackwood's targets --- sprang to life as good characters always do, essentially of their own volition, with no need to write profiles of them or think their story through before sitting down at the keyboard. They told me who they were and why I had to write about them.

BRC: The book, besides being an entertaining read, seems to ask some big questions about innocence and evil. Is there a particular idea about good and evil that you are trying to get across, or do you want readers to draw their own conclusions?

DK: I always prefer to let the reader see --- or not see --- the subtext of a novel. But I will say that everything that happens is made possible by a weakness of the lead character, John Calvino. John's parents and sisters were murdered by Blackwood 20 years earlier, and although as a boy of 14 he killed Blackwood, he has ever since felt profoundly responsible for what happened to his family. Because he refused to trust in the forgiveness that comes with confession and genuine contrition, he has obsessed about his guilt all these years, and his obsession is what opens the door between worlds, letting Blackwood in again, putting John's wife and kids at risk. Why is evil drawn to innocence, to destroy beauty rather than possess it, to make chaos where order had previously ruled, or to insist that art be ugly and that what is not ugly be eradicated? This is a novel in part about redemption. How are we redeemed --- by our actions alone, by faith alone, or by a combination of the two?

BRC: You have written that Alton Turner Blackwood, the embodiment of evil and ruin in this novel, has affected you more than other evil characters you've created. Why? Is he the scariest? The most real?

DK: Well, for one thing, I saw him in those three dreams. He was so vivid that it seemed as if, in sleep, I was looking at a real man in some parallel universe separated from ours by a curtain of space-time that briefly parted. Then there is his monstrousness, which makes of him an archetype, not merely an evil man but a symbol of all human evil, of the twisted soul with which we're born and with which we need to struggle all our lives.

I write novels of hope, as you know, but they're written from a point of view that sees the human condition as fundamentally tragic. And even though he has embraced evil, Blackwood is a tragic figure, too. He was born to a high place, into a wealthy family, and was not evil as a boy. His deformities are a kind of inherited stigmata, the external manifestation of his family's great wickedness, which inevitably suggests that suffering because of his appearance might purify his soul, depending on what he makes of his free will. He could have been the hunchback of Notre Dame instead of a killer. In fact, as I wrote WHAT THE NIGHT KNOWS, I was always aware that an equally valid story could have featured Blackwood in the role of hero as, from boyhood, he endured and ultimately triumphed over the dark world of Crown Hill, the Blackwood family estate. It's very possible that I will eventually be driven to write that alternate story.

BRC: A lot of the story centers on children (or the childhoods of adult characters). Which child character did you enjoy writing the most and why? Does writing from the perspective of a child present any particular challenges?

DK: Each has a voice so different from the other, and I loved each equally. Once in a while, some critic will say, "Oh, I have children, and the children in this book are nothing like mine. The children in this book are too smart for their ages, wise beyond their years, too funny, children just aren't like this." My answer to that is that I had no interest in writing about your children.

I wanted to write about children raised in a highly stimulating intellectual environment, children whose imaginations were encouraged and whose creative abilities were nurtured without surcease. I have known many kids like this, and I've always suspected that they didn't necessarily have higher IQs than other kids, that they were lucky to have parents who created an environment that acknowledged the mysterious nature of life, that allowed the consideration of the transcendent, that inspired a sense of wonder --- homes in which the numinous was almost as common as the mundane.

If you look back to the Victorian era, hardly more than a century ago, children of 12 and 13 were little adults, more mature and knowledgeable than half the middle-aged people of our time. The excruciating attenuation of intellectual/emotional childhood only evolved after World War II. I receive letters from kids as young as 11 and 12 who not only read my books but also write astonishingly insightful letters, so not everyone has embraced the infantilization of society. Ray Bradbury's deeply wise and extravagantly imaginative child characters in books like SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES or DANDELION WINE inspire the reaction, “Yes, that's how it was for me; the world was so much bigger then; the world was HUGE and strange and so very wonderful!” If we let it, the world shrinks as we grow older. If we allow the world to shrink, we must forget how magical it once was to us and how fiercely we embraced it, because if we do not forget, we will live in constant distress that we have traded wonder and wisdom for the blandness of materialism.

BRC: WHAT THE NIGHT KNOWS tells a story from the point of view of many characters. Is that kind of book more difficult to write? What advantages do multiple viewpoints give readers and give you as a writer?

DK: Books in the Odd Thomas series are written in the first person, and they are no easier for me than books written in the third person from many points of view. Some stories require a small canvas, some a large one.

The challenges of writing a book with many points of view are primarily two. First, you have to be careful to stay within one viewpoint in each scene; if you don't, the reader becomes aware of the author's presence, and easy suspension of disbelief becomes impossible. Second, every character's voice needs to be different from the voices of others in the book. When I'm writing in Naomi's P.O.V., she sounds very different from her brother Zach and different, as well, from her sister Minnie, who is younger than Naomi but much more emotionally mature, a genuine old soul.

In my opinion, if every character in a multiple-viewpoint novel sounds like every other, the author has forfeited one of the greatest advantages of this narrative approach: the musicality that arises (metaphorically speaking) from the pitch changes, and the greater sense of reality that a marked difference in voices ensures. At the same time, however, you have to find approaches to the material that bind all the voices together, that bring to the narrative a singular underlying sensibility. A multiple-viewpoint book needs to be like a stream with countless currents and eddies that nevertheless moves always in the same direction, sweeping the reader along.

BRC: You play with some traditional ghost story conventions in your new book. What can you share with us about how ghost stories have been told or shared with you in your own life? Do you have any favorite ghost stories, literary or traditional?

DK: Another publication asked me to pick my five favorite novel-length ghost stories. I thought I'd have a hard time winnowing the wealth of such literature down to only five. Instead, when I began to search my library shelves, I discovered that compared to other genres, few ghost stories have been published. Indeed, I could barely come up with five that I admired, and at least one of them is not a book that most people think of as a ghost story: A CHRISTMAS CAROL by Charles Dickens. The others were THE TURN OF THE SCREW by Henry James, which is not quite novel length, THE SHINING by Stephen King, HELL HOUSE by Richard Matheson and THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE by Shirley Jackson.

Maybe I'm forgetting others or just haven't read them. But I suspect few writers have tackled the genre because (1) They don't believe in an afterlife and aren't comfortable faking it, or (2) They've thought about the form deeply enough to realize how daunting it is to create and work within fair rules for such a story, and how difficult it is to write a hopeful story when the antagonist is an indestructible and supernaturally powerful entity.

BRC: This book has everything: ghosts, a demon, serial killers, petty thugs, maniacal patriarchs, corrupt cops and more. Do any of these scare you more than others?

DK: The capacity of human beings to commit evil scares me more than any ghost ever could. Which is not an invitation to ghosts. I am not issuing a challenge here.

BRC: Willard, a friendly ghost of a golden retriever, shows up toward the end of the book. Did you plan to have a golden retriever in the story somewhere all along?

DK: No. Nothing about writing is more fascinating to me than the way that things sometimes appear in books without being planned, almost without your conscious intent --- and then prove to be part of a web of uncalculated details that have powerful meaning. In this story, Willard's death, John's near-death in a showdown with a criminal (for which he received an award for valor), Minnie's near-fatal illness, and other unsettling events all turn out to date back two years, give or take a month. In essence, something went wrong in their lives at that time, some protection was lifted, and it was then that it became inevitable that Blackwood would return to haunt them. It so happens that a person of great spiritual influence on their family, a person Minnie loved very much, was no longer in their lives, and the person who stepped into his shoes two years ago failed the Calvino family in a key way. The moment I realized all this, in a scene with Minnie in Chapter 48, the hairs literally stood up on the back of my neck.

BRC: The Calvino family is artistic and imaginative. In the story, that creativity can be dangerously manipulated by negative forces if the characters are not careful. Do you think there's danger in unchecked imagination, or is that idea just a good literary theme?

DK: Both. The point is made in the book that, although we universally celebrate imagination, it is in fact a power that can uplift us and save us --- or as easily demean and destroy us. Mozart imagined great music. Hitler imagined death camps and built them. Everything begins as an idea, imagined before it is made real. Aristotle imagined a world of meaning and purpose. Nietzsche imagined a nihilistic world that inspired Hitler. The most dangerous and destructive works of imagination are the various utopias people have dreamed of bringing into reality in this world. Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Po and many others made the 20th century the bloodiest in history by imagining utopias. In the novel, Naomi's high-flying imagination is one of her charms, but also her greatest weakness, because sometimes --- and just when it's most dangerous --- her imagination becomes untethered from reality, and the imaginative-but-grounded girl she could be does a fade and is replaced by a reckless Naomi who wants what could never be.

BRC: What are you reading now? Are there any books you've recently read that have wowed you?

DK: I just reread the late Philip Rieff's nonfiction trilogy of sociological analysis and philosophical criticism of contemporary culture, which I could probably read a hundred times and still find illuminating and inspiring. In fiction, I read an advance proof of Michael Koryta's THE CYPRESS HOUSE, which greatly impressed me, so much so that I went back and read his previous book, SO COLD THE RIVER, which is terrific. If I may be presumptuous, it seems to me that Michael writes with that quantum-mechanics awareness that has long influenced my own work: the recognition that the only real thing is the present moment, where we take the actions that decide our fate, but also that the present moment is formed not only by our actions but by the past, and not only by the past but by the future.

The physicist Yakir Aharonov recently received the National Medal of Science for, in addition to other things, recognizing that among the tiny particles in the quantum domain, the future can have as much influence on the present as does the past. If this is true in the quantum domain --- and it is --- then it may well be true on the macro scale. Perhaps the arrow of time does not fly in one direction, after all. Perhaps in the universe as a whole, as in the quantum domain, time flows forward to the present moment and backward to the present moment, which would strongly argue that the universe has a destiny and that it works continuously to achieve that destiny. That knocks you flat, huh? We've spent a couple of centuries dismissing the ideas of meaning and destiny --- and now the most fundamental science of all, physics, suggests that we have one.

T.S. Eliot wasn't a physicist, but he opened "Burnt Norton" with the lines "Time present and time past/ Are both perhaps present in time future/ And time future contained in time past/ If all time is equally present/ All time is unredeemable." Not to put too heavy a load on Michael Koryta's broad shoulders, but I suspect he either recognizes this consciously or intuits it, which is why his work resonates into deeper strata than does most of what I read.

BRC: And now the obligatory "what's next" question! Are there any new scary or psychological themes you want to explore, or any classic suspense themes you hope to return to soon?

DK: Life is so jam-packed with wonder, with mystery, and people are so splendidly diverse that there is always something fresh to write about and new characters to explore. The fifth and finalFrankenstein comes out late this spring. I'm currently finishing a big bad-house novel, but it's not another ghost story. Something far stranger than ghosts is at work in this old Beaux Arts mansion built in the 1800s. I don't have a title yet. Then on to the fifth Odd Thomas. I've begun to suspect that I'm never going to have time to take that degree in dentistry.

• Click here now to buy this book from Amazon.