Excerpt

Excerpt

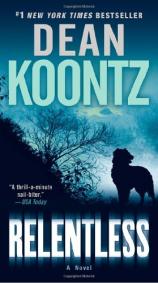

Relentless

Chapter One

This is a thing I’ve learned: Even with a gun to my head, I

am capable of being convulsed with laughter. I am not sure what

this extreme capacity for mirth says about me. You’ll have to

decide for yourself.

Beginning one night when I was six years old and for twenty-seven

years thereafter, good luck was my constant companion. The guardian

angel watching over me had done a superb job.

As a reward for his excellent stewardship of my life, perhaps my

angel—let’s call him Ralph—was granted a

sabbatical. Perhaps he was reassigned. Something sure happened to

him for a while during my thirty-fourth year, when darkness found

us.

In the days when Ralph was diligently on the job, I met and courted

Penny Boom. I was twenty-four and she was twenty-three.

Women as beautiful as Penny previously looked through me. Oh,

occasionally they looked at me, but as though I reminded them of

something they had seen once in a book of exotic fungi, something

they had never expected—or wished—to see in real

life.

She was also too smart and too witty and too graceful to waste her

time with a guy like me, so I can only assume that a supernatural

power coerced her into marrying me. In my mind’s eye, I see

Ralph kneeling beside Penny’s bed while she slept,

whispering, “He’s the one for you, he’s the one

for you, no matter how absurd that concept may seem at this moment,

he really is the one for you.”

We were married more than three years when she gave birth to Milo,

who is fortunate to have his mother’s blue eyes and black

hair.

Our preferred name for our son was Alexander. Penny’s mother,

Clotilda—who is named Nancy on her birth

certificate—threatened that if we did not call him Milo, she

would blow her brains out.

Penny’s father, Grimbald—whose parents named him

Larry—insisted that he would not clean up after such a

suicide, and neither Penny nor I had the stomach for the job. So

Alexander became Milo.

I am told that the family’s surname really is Boom and that

they come from a long line of Dutch merchants. When I ask what

commodity his ancestors sold, Grimbald becomes solemn and evasive,

and Clotilda pretends that she is deaf.

My name is Cullen Greenwich—pronounced gren-itch, like the

town in Connecticut. Since I was a little boy, most people have

called me Cubby.

When I first dated Penny, her mom tried calling me Hildebrand, but

I would have none of it.

Hildebrand is from the Old German, and means “battle

torch” or “battle sword.” Clotilda is fond of

power names, except in the case of our son, when she was prepared

to self-destruct if we didn’t give him a name that meant

“beloved and gentle.”

Our friend and internist, Dr. Jubal Frost, who delivered Milo,

swears that the boy never cried at birth, that he was born smiling.

In fact, Jubal says our infant softly hummed a tune, on and off, in

the delivery room.

Although I was present at the birth, I have no memory of

Milo’s musical performance because I fainted. Penny does not

remember it either, because, although conscious, she was distracted

by the postpartum hemorrhaging that had caused me to pass

out.

I do not doubt Jubal Frost’s story. Milo has always been full

of surprises. For good reason, his nickname is Spooky.

On his third birthday, Milo declared, “We’re gonna

rescue a doggy.”

Penny and I assumed he was acting out something he had seen on TV,

but he was a preschooler on a mission. He climbed onto a kitchen

chair, plucked the car keys from the Peg–Board, and hurried

out to the garage as if to set off in search of an endangered

canine.

We took the keys away from him, but for more than an hour, he

followed us around chanting, “We’re gonna rescue a

doggy,” until to save our sanity, we decided to drive him to

a pet shop and redirect his canine enthusiasm toward a gerbil or a

turtle, or both.

En route, he said, “We’re almost to the doggy.”

Half a block later, he pointed to a sign—animal shelter. We

assumed wrongly that it was the silhouette of a German shepherd

that caught his attention, not the words on the sign. “In

there, Daddy.”

Scores of forlorn dogs occupied cages, but Milo walked directly to

the middle of the center row in the kennel and said, “This

one.”

She was a fifty-pound two-year-old Australian shepherd mix with a

shaggy black-and-white coat, one eye blue and the other gray. She

had no collie in her, but Milo named her Lassie.

Penny and I loved her the moment we saw her. Somewhere a gerbil and

a turtle would remain in need of a home.

In the next three years, we never heard a single bark from the dog.

We wondered whether our Lassie, following the example of the

original, would at last bark if Milo fell down an abandoned well or

became trapped in a burning barn, or whether she would instead try

to alert us to our boy’s circumstances by employing urgent

pantomime.

Until Milo was six and Lassie was five, our lives were not only

free of calamity but also without much inconvenience. Our fortunes

changed with the publication of my sixth novel, One O’Clock

Jump.

My first five had been bestsellers. Way to go, Angel Ralph.

Penny Boom, of course, is the Penny Boom, the acclaimed writer and

illustrator of children’s books. They are brilliant, funny

books.

More than for her dazzling beauty, more than for her quick mind,

more than for her great good heart, I fell in love with her for her

sense of humor. If she ever lost her sense of humor, I would have

to dump her. Then I’d kill myself because I couldn’t

live without her.

The name on her birth certificate is Brunhild, which means someone

who is armored for the fight. By the time she was five, she

insisted on being called Penny.

At the start of World War Waxx, as we came to call it, Penny and

Milo and Lassie and I lived in a fine stone-and-stucco house, under

the benediction of graceful phoenix palms, in Southern California.

We didn’t have an ocean view, but didn’t need one, for

we were focused on one another and on our books.

Because we’d seen our share of Batman movies, we knew that

Evil with a capital E stalked the world, but we never expected that

it would suddenly, intently turn its attention to our happy

household or that this evil would be drawn to us by a book I had

written.

Having done a twenty-city tour for each of my previous novels, I

persuaded my publisher to spare me that ordeal for One

O’Clock Jump.

Consequently, on publication day, a Tuesday in early November, I

got up at three o’clock in the morning to brew a pot of

coffee and to repair to my first-floor study. Unshaven, in pajamas,

I undertook a series of thirty radio interviews, conducted by

telephone, between 4:00 and 9:30 a.m., which began with morning

shows on the East Coast.

Radio hosts, both talk-jocks and traditional tune-spinners, do

better interviews than TV types. Rare is the TV interviewer who has

read your book, but eight of ten radio hosts will have read

it.

Radio folks are brighter and funnier, too—and often quite

humble. I don’t know why this last should be true, except

perhaps the greater fame of facial recognition, which comes with

regular television exposure, encourages pridefulness that ripens

into arrogance.

After five hours on radio, I felt as though I might vomit if I

heard myself say again the words One O’Clock Jump. I could

see the day coming when, if I was required to do much publicity for

a new book, I would write it but not allow its publication until I

died.

If you have never been in the public eye, flogging your work like a

carnival barker pitching a freak show to the crowd, this

publish-only-after-death pledge may seem extreme. But protracted

self-promotion drains something essential from the soul, and after

one of these sessions, you need weeks to recover and to decide that

one day it might be all right to like yourself again.

The danger in writing but not publishing was that my agent, Hudson

“Hud” Jacklight, receiving no commissions, would wait

only until three unpublished works had been completed before having

me killed to free up the manuscripts for marketing.

And if I knew Hud as well as I thought I did, he would not arrange

for a clean shot to the back of the head. He would want me to be

tortured and dismembered in such a flamboyant fashion that he could

make a rich deal for one of his true-crime clients to write a book

about my murder.

If no publisher would pay a suitably immense advance for a book

about an unsolved killing, Hud would have someone framed for it.

Most likely Penny, Milo, and Lassie.

Anyway, after the thirtieth interview, I rose from my office chair

and, reeling in self-disgust, made my way to the kitchen. My

intention was to eat such an unhealthy breakfast that my guilt over

the cholesterol content would distract me from the embarrassment of

all the self-promotion.

Dependable Penny had delayed her breakfast so she could eat with me

and hear all of the incredibly witty things I wished I had said in

those thirty interviews. In contrast to my tousled hair, unshaven

face, and badly rumpled pajamas, she wore a crisp white blouse and

lemon-yellow slacks, and as usual her skin glowed as though it were

translucent and she were lit from inside.

As I entered the room, she was serving blueberry pancakes, and I

said, “You look scrumptious. I could pour maple syrup on you

and eat you alive.”

“Cannibalism,” Milo warned me, “is a

crime.”

“It’s not a worldwide crime,” I told him.

“Some places it’s a culinary preference.”

“It’s a crime,” he insisted.

Between his fifth and sixth birthdays, Milo had decided on a career

in law enforcement. He said that too many people were lawless and

that the world was run by thugs. He was going to grow up and do

something about it.

Lots of kids want to be policemen. Milo intended to become the

director of the FBI and the secretary of defense, so that he would

be empowered to dispense justice to evildoers both at home and

abroad.

Here on the brink of World War Waxx, Milo perched on a dinette

chair, elevated by a thick foam pillow because he was diminutive

for his age. Blue block letters on his white T-shirt spelled

courage.

Later, the word on his chest would seem like an omen.

Having finished his breakfast long ago, my bright-eyed son was

nursing a glass of chocolate milk and reading a comic book. He

could read at college level, though his interests were not those of

either a six-year-old or a frat boy.

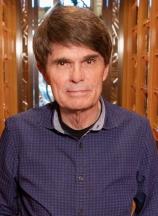

Excerpted from RELENTLESS © Copyright 2011 by Dean Koontz.

Reprinted with permission by Bantam. All rights reserved.