Excerpt

Excerpt

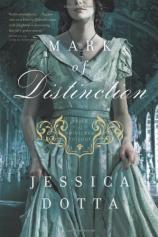

Mark of Distinction: Price of Privilege Trilogy, Book 2

One

The eight months following my arrival at Maplecroft have been called one of the greatest cozenages of our age. My father and I have endured endless speculation as to the number of hours poured into its plan and execution.

Truth comprised of bare facts is rarely more flattering than legend. In reality, our sham was little more than a mad-dash scramble of one improvisation after another. Events kept unfolding, forcing us to take new action, making it impossible to steer from collision.

I am an old woman now. Ancient some days. I had no idea my story would cause such an uproar. When I first penned it, my only intent was to address the rumors of how the entire affair started. I was weary of hearing how I seduced Mr. Macy. As if I, or anyone, could. The very idea is laughable. Long life has its advantages. Your perception grows clearer, even if your sight dims. How much better I now understand the shock Lady Foxmore must have felt during our presentation. Her pretension was unequalled. Yet there I stood, a pale, scrawny girl in rags, chosen by one of the most illustrious men in her circle to be wed to him. It is no wonder she thought it a grand jest. How could she, or anyone who knew Macy intimately, have guessed just how resolute he was upon marrying me?

Since my story’s publication, I have been accused of besmirching the innocent by fabricating events to gain public sympathy. Some have pointed out that I unfairly suggest Mr. Macy is responsible for Churchill’s murder. They remind me that it is a documented fact that the culprit, an unstable man, was apprehended—and that it’s nothing more than coincidence Churchill’s death occurred on the same day Mr. Macy collected me.

Others state that if I were truly innocent, then how is it that my story escalated to treason and then ended so tragically?

It is this last challenge that causes me unrest. I cannot recount the mornings I’ve stood before my window, debating whether it is best to allow the matter to rest or to persevere and tell the tale in its entirety. I’ve wrestled with my conscience, wondering what good revealing all would do. Shall I so easily expose the sins of my father? Like Ham, shall I peel back the tent flap that covers his nakedness to the world? Will it bring back the dead?

It was only this morning, as I turned to retreat to my favorite chair, that I was decided. I caught sight of my paternal grandmother, Lady Josephine, watching me. She is ageless, of course, forever capturing the bloom of our youth. As I paused and studied her painting, my great-grandchildren rushed past my window, tripping on their own merry shrieks. They fell in a muddle in the middle of the grounds and then, just for the glory of it, lay on their backs, spread their arms, and laughed.

I chuckled, imagining their incredulousness were they to learn my frolics were once as madcap as theirs. Lady Josephine also watched with her ever-present, coy smile. For some reason it brought to mind how her portrait gave me strength during those long months with my father. Something about her smile used to assure me that her antics were equally mischievous. I regret that I will never learn about them.

It is this thought that decides me.

I will for my grandchildren and great-grandchildren to know me.

Not the version they’ll find archived in the newspapers. Heaven forbid they search there! I care not to contemplate the opinions they’d form. No, I will write this wrong. Let them at least judge me by truth, though who can say whether it makes me less of a culprit. Let the world think what it will. I am far too old to care, anyway. I am past the point of cowing to opinions.

It all began, of course, with my father.

Not my stepfather, William Elliston, who I believed, until that devastating night I wed Mr. Macy, had begotten me.

But Lord Pierson himself.

The second time I laid eyes on him was on my eighteenth birthday.

Mama had always made a secret celebration of that date, sneaking into my chamber before dawn. The scent of lilac clung to her rustling skirts as she’d motion me to make room for her to climb into my bed.

“You were born at this very hour.” Her voice could soothe even the darkness as she settled into the down pillows.

On every birthday, even until my seventeenth, I was wont to curl against her, resting my head against her collarbone, where I listened to her heart. Rare were the moments we were granted a respite. I have little doubt we both savored those mornings.

“The sun had just peeked over the hillocks outside my window,” Mama would continue, intertwining our fingers. “I was exhausted, and by the looks the midwife and Sarah exchanged, I knew they believed it was hopeless.” Here, determination coated Mama’s voice as if she were reliving the moment. “I fastened my gaze on that tiny flush of light and swore by the time the sun was fully risen, you’d be born. You were the only family I had left, and I wasn’t about to allow either one of us to die.”

I always held my breath, hoping she’d elaborate. Those birthday moments were the closest Mama ever came to speaking about her past.

“You were born just as the sun crested the horizon. Your wail was the loudest the midwife had ever heard. She nearly dropped you in surprise. Here, she thought you’d be stillborn, but you came out kicking and screaming.”

Next, she’d splay her hand against mine, palm against palm, measuring my growth. It seems odd now that on my seventeenth birthday—my last birthday with Mama—our hands were exactly the same size.

“I counted your fingers and toes, over and over. You were so tiny and perfect.” Even as a child I noted how her chest would rise in a silent sigh before saying, “Your father came that night. He burst through the doors and looked wildly about the room for you. He, also, marveled over you. And he, too, counted your toes and fingers over and over, as if the number would change.”

Though I never had a chance to tell her, those birthday mornings were the most treasured part of my splintered childhood.

Thus for me to rise on my eighteenth birthday in order to watch the coming dawn was the most costly tribute I could pay her. It fractured me. Yet failing to honor Mama would have felt worse.

Wind shook the windowpanes as I stumbled from the bed and groped in the semidark for matches. The odor of phosphorus filled the air as I lit candles along the mantel.

During the night, the fire had burned into ashes, leaving my room so cold it hurt my throat to breathe the wintry air. I rubbed my hands over my arms as I went to my father’s late wife’s wardrobe and selected a thick shawl.

I glanced at the fireplace as I passed it again, wondering why the servants had not kept the fires lit. Never having lived in a great house, it was impossible to tell if the fault was the staff’s or mine. It was just as likely I’d forgotten to give the necessary instruction as it was that some servant had neglected her duty.

Regardless of the reason, the timing could not have been worse. The freezing temperature served to sharpen the harrowing sensation that Mama was truly gone.

I turned my gaze toward the clock and estimated it to be about a half hour before sunrise. I knew that if I returned to the warmth of bed, I risked falling asleep and missing daybreak. Uncertain what else to do, I retreated to the window seat and brushed aside the heavy lace hanging before the window.

Though it was early morning, pewter-grey clouds layered the sky. Only traces of the previous night’s snow remained on the ground, tucked amongst the roots of oak trees and glistening between the crags of rocks. A solitary snowflake floated down from the leaden sky. Like me, it didn’t seem to belong anywhere but drifted from one spot to another, never quite landing. With numb fingers, I clutched my shawl closer and rested my head against the window.

“I’m here, Mama,” I whispered, hoping to feel her presence.

But I felt nothing. All evidence of Mama had been successfully scrubbed from my life. Even the nightmares of her screaming warnings to me from across a chasm had stopped. My fingertips curled against the empty space near my collarbone. I hadn’t even managed to keep her locket a full year. Was it only last year that she’d given me the gold necklace containing her and William’s likeness? With a splurge of self-pity, I realized I still needed Mama. I wanted her to stroke and kiss my brow, telling me she hadn’t been murdered, and I hadn’t married her murderer. I wanted to be home, which no longer existed because Mr. Macy gave it away to prevent me from hiding from him there.

I swallowed, but it was too late. I choked out a ragged gasp before I hastily wiped my wet eyes with the hem of the shawl.

Refusing to cry further, I shifted position on the window seat and forced myself to find new occupation. Wind scattered the snow crusting the bare trees, creating a mist that waned the view where the sun worked to rise. I waited until it dissipated, then traced the grove of staggering hemlocks that filled the ravine separating my father’s Maplecroft estate and the adjoining property. As if drawn against my will, I followed the course all the way to Eastbourne.

Smoke curled from the tall chimneys of Mr. Macy’s vast estate, spreading ash over snow-strewn roofs, where gargoyles hunched beneath snowy capes. It appeared serene, betraying nothing of the evil that lurked there. Everything familiar to me had been stripped away within those walls, where I’d spent a week of my life . . . and betrayed Edward by trusting Mr. Macy and marrying him instead. I touched the cold pane, my stomach hollowing as I wondered if he knew yet that I was hiding from him in plain view.

As the sky grew pearlier, it became easier to see Macy’s servants scurrying over the grounds, shoveling snow and attending to their duties. It was impossible to imagine that only a fortnight ago I had been amongst them, my heart soaring with the intrigue.

That period of time stood in stark contrast to the time I’d spent in my father’s house.

For eight days I’d not encountered a soul, except for the timid maid who crept soundlessly into my chamber to kindle my fire and dress me. Heartsick after Edward’s departure, I’d wandered aimlessly through empty rooms and echoing marble halls. My first morning alone, I’d searched the estate looking for private nooks I could duck into to read or sew if I needed solitude. I wanted time to heal and to sort through my emotions. Yet as I took each meal alone and passed hours in silence, straining to catch the sound of another’s voice, I learned my search had been unwarranted. No one would disturb me. The entire estate seemed under a deep freeze, waiting for its thaw, and I’d been swallowed by its vastness.

As if to combat the thought, a warm, glowing orb of light suddenly reflected in the window. I turned in time to see Mrs. Coleman, the housekeeper of Maplecroft, entering my chamber, carrying a whale-oil lamp. The white fabric that crisscrossed her bodice showed traces of ash, revealing she’d tended duties uncommon for a housekeeper. Her eyes widened in dismay when she noted me awake. Her next thought was apparent by the despairing look she gave my empty grate.

She placed the lamp aside and straightened her shoulders. “I beg your pardon, Miss Pierson. Seven of my girls are down with a wicked chest cold. Not that it is a proper excuse, mind you.”

The name Miss Pierson chafed me like carpenter’s paper and made me feel as twisted as the touchwood used to light the fire. I hated allowing the staff to believe I was Lord Pierson’s legitimate daughter, but until my father returned, I wasn’t certain how to conduct myself.

The housekeeper cocked her eyebrows, waiting.

I frowned, feeling as though I were committing a great social blunder. Yet for the life of me, I couldn’t think of how the mistress of an estate would handle such a matter. Several replies came to mind, but somehow they all felt wrong.

Apparently silence was equally appalling, for Mrs. Coleman snapped her eyes shut and gave a quick shake of her head as if to ask what they were teaching young ladies these days. When she opened her eyes again, I had little doubt as to the true mistress of Maplecroft.

“Naturally—” she stepped smartly into the chamber, the keys at her hip jangling sharply—“you wish to know whether I’ve summoned the apothecary and whether any of Eaton’s staff is down, as well. I’m assured that at least two of the girls will be on their feet tomorrow. William, our second, has the malady, but James is managing quite well by himself. Some of the grooms are starting to look feverish, but that shouldn’t inconvenience your father when he returns home tonight.”

Eaton’s name I recognized as the butler’s. I had only just worked out that William was a footman, because James was, when my mind seized upon Mrs. Coleman’s last statement. I rose to my feet. “Did you say that my father is expected tonight?”

“That I did. ’Tis just like him too. Changing plans and returning home with a guest right in the middle of a grippe outbreak.”

I gathered and pulled my hair over my shoulder as dread tingled through my body.

“You don’t look well yourself.” Mrs. Coleman approached and touched my forehead with the back of her fingers. “Well, at least you’re cool to the touch. Nonetheless, you need to eat better. You’re thinner than is healthy. You had naught yesterday except that bite of porridge and biscuit.”

I gawked, envisioning members of the staff spying on me through keyholes. I had been certain I was alone when I only managed one swallow of gruel. I’d pushed the entire tray away, missing Edward too keenly to eat. Had they watched while I cried too?

“Here now, there’s no need to appear shocked.” Mrs. Coleman maneuvered to the hearth. “Since you arrived, the staff has been barmy with talk of you.” She paused to meet my eye. “Not that I’ve allowed it, mind you.”

Her nonchalance gave me pause. I now couldn’t decide whether I had been spied upon, or if she generally meant I barely touched the tray that was delivered to my room.

“I’ve been waiting for you to find your way to my room,” she said. “I warrant at your school they placed great emphasis on the importance of keeping a distinction between yourself and your staff. If you were to ask my opinion on it, I would tell you it was stuff and nonsense. Maplecroft, ’tis a lonely house to become acquainted with, to be sure. Your mother wasn’t above coming to my rooms and visiting me, let me tell you. You would find me grateful for the occasional visit.”

Her speech awoke a myriad of reactions within me, so that each word spiralled my thoughts in a different direction. It stunned me to learn that the staff had interpreted my isolation as pretentiousness. Had they expected me to seek them out, to take interest and assign them their duties? I had no right to do so, not at least until I saw my father. For I wasn’t entirely certain he wouldn’t ship me off somewhere. I hadn’t forgotten that before the entire affair started, he’d planned to tuck me out of sight by sending me to Scotland as a servant. Lastly, the manner in which the housekeeper took it upon herself to lecture reminded me greatly of Nancy. My throat tightened, and my homesickness crested as I wondered what happened to my outspoken lady’s maid.

Thankfully, Mrs. Coleman had her back to me and therefore didn’t witness my struggle to hold back emotions. She knelt over the grate, raking the ashes.

“I always keep a cake in my shelf,” she continued. “If you like, you are invited to join me for tea in the late afternoons. You may sit in my overstuffed chair and confide all your little secrets to me. I should rather enjoy that.”

I crossed my arms, wondering what she’d do if I actually took up her offer and confided all. I allowed myself a wry smile as I imagined her too shocked to speak.

“You’ll find that Master Isaac doesn’t consider it below his station to come and visit me. I daresay you can trust him to determine what is right and proper, far above any nonsense your school taught you.” Using tongs, she lifted the half-burnt coals from the ash and deposited them into a nearby scuttle.

I frowned, not certain who Master Isaac was, but then recalled Lord Dalry, the gentleman who’d greeted Edward and me the night we arrived.

The dull chimes of a grandfather clock sounded, filling the chamber and reminding me of my mission. I retreated back to the window. The sun had nearly risen, giving the sky a rosy tincture. With dismay, I glanced at Mrs. Coleman as she started the fire, then cast my gaze outdoors. I desired to be alone, yet there was no polite way to dismiss her midtask.

The sunrise was beautiful. Tones of gold highlighted the claret color, making the sky incarnadine. I ached, uncertain what to make of its beauty. How could the most resplendent sunrise of my life simultaneously be the most painful?

Yet as I considered the complex layers of color and light, I better understood Mama’s determination that first morning. She, too, had lost her entire world. She had to fight and remain determined in order to give birth. To thrive after tragedy, one must find and draw from a pool of strength deep within oneself. Mama must have found hers that morning in me.

I gave a deep sigh, resting my head against the window frame. A newborn daughter, however, was more likely to give someone an iron will than a powerful father. Something about that thought surfaced another part of the story, which Mama had mentioned only once. I was perhaps seven or eight. After she’d described my father counting my fingers and toes, she tacked on, “I never saw a grown man weep over his child before, but your father held you against his chest and expressed such raw emotion that Sarah feared he’d drop you in his remorse.”

That year, I had wrinkled my nose. If William had been weeping at the end of a long night, then he was inebriated. Even at that tender age, I could well guess he’d hidden in a pub during Mama’s labor. It also stood to reason that he probably slept at the tavern, woke, and started drinking again. Knowing William’s temperament, I was displeased that Mama and Sarah had allowed him to handle an infant.

But as I stood there, feeling the cold bleed through the window, I suddenly guessed the truth, and tingles spread over my body. Mama had not been speaking about William, but Lord Pierson.

I held my breath. If my father came to see me on the morning of my birth, then I mattered to him. I raised my gaze, savoring the feeling of hope that surged through me. Perhaps it didn’t matter that our first meeting last month had been horrid, or why I was at Maplecroft pleading for sanctuary. All that counted was what happened next.

“’Tis a grave view, that,” Mrs. Coleman said behind me, nearing me.

I had been so deep in thought, I’d nearly forgotten I wasn’t alone.

She joined me at the window and frowned, glancing toward Eastbourne. “There’s something evil about this, if you ask me. A bad omen, for certain.”

I felt my mouth dry as I turned to look at her.

She pulled the bundle of bedclothes in her arms tighter. “Mark my words: ’twill be the coldest winter yet. Snow in October! I’ve been in this shire for over twenty years, with nary a snowflake before January, much less a storm.”

I released a shaky breath. “You . . . you meant the snow?”

She glanced in my direction. “Whatever else could I have meant?”

Without my permission, my eyes strayed to Eastbourne.

“Humph,” she said, following my gaze, then set aside her linens. With the air of a prim nanny, she surveyed Eastbourne. “Mr. Chance Reginald Macy,” she finally said with distaste. “I take it you’ve followed his dreadful scandal in the paper, then?” She shook her head disapprovingly, the ruffles on her cap bobbing before she stalked to the wardrobe. “Best not let your father hear. He would not approve of your reading such trash. If you ask me, that girl ought to be horsewhipped within an inch of her life. Mind you, I’d like to be the first one who gives her a dressing-down. I can assure you, she’d know her duty when I finished with her.”

Feeling my face grow hot, I turned my back to her. Since my arrival, I’d only glanced at the various newspapers delivered each day, never suspecting that Macy was keeping our scandal alive. I swallowed, realizing that he was still searching for me—or at least pretending to.

The heavy scent of perfume coated the room as she dug through my father’s late wife’s dresses. “As for him, he ought to feel the fool for allowing someone half his age to seduce him. Had he enough self-pride, he would have better sense than to keep adding to the fire, pleading for her return. He’s the same age as your father, you know. Can you imagine your father making such a tomfool of himself over a girl your age? I remember a time when the two of them would ride and hunt together. The year before Mr. Macy left for Eton, he and your father were inseparable.”

“They were?” Surprised by this information, I turned and studied her face. The crow’s-feet that lined her eyes suggested she was only a decade older than Mrs. Windham. She’d have been too young to be a housekeeper back then, which meant she’d have been an upper maid. “What happened?”

She paused and a thoughtful expression crossed her face, as if she were reliving scenes from the past. Then all at once, she tsked. “There’s no sense asking me. I was never given knowledge of the affair. Your father spent that following summer in Bath, and we scarcely saw him. Something happened there that caused the pair to fall out.”

Now this bit of news interested me. Mama’s past was a mysterious maze, of which I’d only learned one or two turns. One of those paths had come from Lady Foxmore. During our first tea, she stated that she’d chaperoned Mama in Bath the summer after Mama’s family perished in a fire. I bit my lip as Mrs. Coleman rifled through dresses. Was it possible it was the same summer that drove a wedge between my father and Mr. Macy?

“Here. This ought to fit.” Mrs. Coleman withdrew a scarlet brocade gown. “It’s none of my business, mind you, but for your mother’s sake, I intend to give your father a piece of my tongue about the condition of your clothing when you arrived. I won’t argue the good of teaching someone of your rank humility, but to keep her dressed in rag—” She stopped short as if recalling whom she addressed.

I pretended to view the grounds again, wanting to kick myself for showing interest in Mr. Macy. Though my common sense had been a bit woolly from the brandy, I still recalled Mr. Macy’s words: “More than one of your guardian’s servants is loyal to me. I’ve been intercepting all correspondence involving you since your mother’s death.”

I crossed my arms, willing myself not to panic, either. Thus far nothing had happened.

“What time does my father arrive?” I asked.

“Likely as not, sometime after gloaming, but with him, there’s no telling,” was Mrs. Coleman’s stout reply as she unfolded and refolded petticoats, looking for one that would fit. “I’ll have to hire girls from the village to have things readied on time. It’s a blessing he didn’t surprise us, considering the state of the house.”

Her statement was so curious, my mouth twisted in a queer smile. I’d never seen as much as a speck of dust in the entire estate.

Aware my father could return any minute, I glanced at the clock. After Mrs. Coleman left my chambers, she wasn’t likely to have the time to assist me later. If I wanted to present my best, I needed to hasten.

While Mrs. Coleman shook out the clothing she’d selected, I opened the small china boxes, looking for face powder to hide the crescents beneath my eyes. Scents of oil of tartar and almond rose from various creams, but I found no white powder. In my fumbling, one of the bottles of fragrance spilled, filling the air with rose water.

Mrs. Coleman eyed the spill as she approached, her mouth tightening. “Never mind it; I’ll tend to it as you put these on.”

While Mrs. Coleman pressed a linen towel against the spill, I shed the nightdress and donned petticoats too large for my frame. Shivering, I stepped into the satin gown that felt soaked in cold.

When I finished, Mrs. Coleman smoothed my hair with pomade, parted it down the middle, and completed it with a simple braid.

“With your permission, I’d like to take my leave now,” she said, setting the brush down.

“Oh yes, yes,” I said. “Feel free.”

Her eyebrows rose as though she was surprised by my unorthodox dismissal. Nonetheless, she dipped and left with the laundry bundled against her hip.

Alone, I pulled out the pins from her hairstyle, changed my part and redistributed the pins into a more flattering style, then studied the girl in the looking glass. I heaved a sigh. I looked like a forlorn child in an oversized ruffled dress, and without Nancy, my hair lacked luster.

Even so, I was determined to be the first to greet my father.

Had I known who my father’s guest was, I doubt I should have bothered.

Mark of Distinction: Price of Privilege Trilogy, Book 2

- Genres: Christian, Christian Fiction, Fiction, Historical Fiction, Historical Romance, Romance

- paperback: 448 pages

- Publisher: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

- ISBN-10: 1414375565

- ISBN-13: 9781414375564