Excerpt

Excerpt

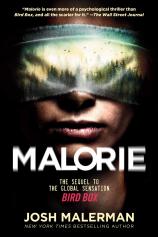

Malorie: A Bird Box Novel

ONE

Tom is getting water from the well. It’s something he’s done every other day for the better part of a decade, the three of them having called Camp Yadin home for that long. Olympia believes the camp was once an outpost in the American frontier days. She’s read almost every book in the camp library (more than a thousand), including books on the history of Michigan. She says the camp lodge was most likely once a saloon. Cabin One was the jail. Tom doesn’t know if she’s right, though he has no reason not to believe her. It was a Jewish summer camp when the creatures came, that much is for sure. And now, it’s home.

“Hand over hand,” he says, taking the rope that connects Cabin Three to the stone lip of the well. He says it because, despite the ropes that tie every building to one another (and even link Cabin Ten to the H dock on the lake), he’s trying to come up with a better way to move about.

Tom loathes the blindfolds. Sometimes, when he’s feeling particularly lazy, he doesn’t use one at all. He keeps his eyes closed. But his mother’s never-ending rules remain firm in his mind.

Closing your eyes isn’t enough. You could be startled into opening them. Or something could open them for you.

Sure. Yes. In theory Malorie is right. In theory she usually is. But who wants to live in theory? Tom is sixteen years old now. He was born into this world. And nothing’s tried to open his eyes yet.

“Hand over hand.”

He’s almost there. Malorie insists that he check the water before bringing it up. She’s told him the story of two men named Felix and Jules many times. How his namesake, Tom the man, tested the water the two brought back, the water everybody was worried could be contaminated by a creature. Tom the teen likes that part of the story. He relates to the test. He even relates to the idea of new information about the creatures. Anything would be more to work with than what they have. But he’s not worried about something swimming in their drinking water. The filter he invented himself has taken care of that.

And besides, despite the way Malorie carries on, even she can’t believe water can go mad.

“Here!” he says.

He reaches out and touches the lip before bumping into it. He’s made this walk so many times that he could run it and still stop before the stone circle.

He leans over the edge and yells into the dark tunnel.

“Get out of there!”

He smiles. His voice echoes—the sound is a rich one—and Tom likes to imagine it’s someone else calling back up to him. For as lucky as they are to have chanced upon an abandoned summer camp with numerous buildings and amenities, life gets lonely out here.

“Tom is the best!” he hollers, just to hear the echo.

Nothing stirs in the water below, and Tom begins to bring the bucket up. It’s a standard crank, made of steel, and he’s repaired it more than once. He oils it regularly, too, as the camp giveth in all ways; a supply cellar in the main lodge that brought Malorie to tears ten years ago.

“A pipeline that delivers water directly to us,” Tom says, cranking. “We could put it exactly where the rope is now. It passes through the existing filter. All we’d have to do is turn a dial, and presto. Clean water comes right to us. No more hand over hand on the rope. We wouldn’t have to leave the cabin at all.”

Not that the walk is difficult. And any excuse to get outside is a good one. But Tom wants things to improve.

It’s all he thinks about.

The bucket up, he removes it from its hooks and carries it back to Cabin Three, the largest of the cabins, the one he, Olympia, and Malorie have slept in most of these years. Mom Rules won’t allow Tom or Olympia to sleep anywhere else, despite their growing needs, a rule that Tom has so far followed.

Spend all day in another one if you need to. But we sleep together.

Still. A decade in.

Tom shakes his head and tries to laugh it off. What else is there to do? Olympia has told him in private about the differences in generations that she’s read about in her books. She says it’s common for teenagers to feel like their parents are “from another planet.” Tom definitely agrees with the writers on that front. Malorie acts as if every second of every day could be the moment they all go mad. And Tom and Olympia both have pondered aloud, in their own ways, the worth of a life in which the only aim is to keep living.

“Okay, Mom,” Tom says, smiling. It’s easier for him to smile about this stuff than not. The few times outsiders have passed through their camp, their home, Tom has been able to glean how much stricter Malorie is than most. He’s heard it in the voices of others. He saw it regularly at the school for the blind. Often, it was embarrassing, living under her thumb in public. People looked at her like she was. . . . what’s the word Olympia used?

Abusive.

Yes. That’s it. Whether or not Olympia thinks Malorie is abusive doesn’t matter. Tom thinks she is.

But what can he do? He can leave his blindfold inside. He can keep notes and dream of inventing ways to push back against the creatures. He can refuse to wear long sleeves and a hood on the hottest day of the year. Like today.

At the cabin’s back door, he hears movement on the other side. It’s not Olympia, it’s Malorie. This means he can’t simply open the door and place the bucket of water inside. He needs to put that hood on after all.

“Shit,” Tom says.

So many little dalliances, so many quirks of his mother’s that get in the way of him existing on his own, the way he’d have it done.

He sets the bucket in the grass and takes the long-sleeved hoodie from the hook outside. His arms through the sleeves, he doesn’t bother with the hood. Malorie will only check an arm.

The bucket in hand again, he knocks five times.

“Tom?” Malorie calls.

But who else would it be?

“Yep. Bucket one.”

He will gather four buckets today. The same number he always retrieves.

“Are your eyes closed?”

“Blindfolded, Mom.”

The door opens.

Tom hands the bucket over the threshold. Malorie takes it. But not without touching his arm in the process.

“Good boy,” she says.

Tom smiles. Malorie hands him a second bucket and closes the door. Tom removes the hoodie and puts it back on the hook.

It’s easy to fool your mom when she’s not allowed to look at you.

“Hand over hand,” he says. Though really now he’s just walking alongside the rope, bucket in one hand. Malorie’s told him many times how they did it in the house on Shillingham, the house where Tom was born. They tied the rope around their waists and got water in pairs. Olympia says Malorie talks about that house more often than she realizes. But they both know she only talks about it up to a point. Then, nothing. As if the ending of the story is too dark, and repeating it might bring it back upon her.

At the well, his arms bare below the short sleeves, Tom secures the second bucket and turns the crank. The metal clangs against the stone as it always does but despite the contained cacophony, Tom hears a foot upon the grass to his left. He hears what he thinks are wheels, too.

A wheelbarrow pushed past the well.

He stops cranking. The bucket takes a moment to settle.

Someone’s here. He can hear them breathing.

He thinks of the hoodie hanging on the hook.

Another step. A shoe. Dry grass flattens in a different way beneath a bare foot than it does the solid sole of a shoe.

A person, then.

He does not ask who it is. He doesn’t move at all.

A third step and Tom wonders if the person knows he’s here. Surely they had to have heard him?

“Hello?”

It’s a man’s voice. Tom hears paper rustling, like when Olympia flips pages while reading. Does the man have books?

Tom is scared. But he’s thrilled, too.

A visitor.

Still, he does not answer. Some of Malorie’s rules make more sense in the moment.

Tom steps away from the well. He could run to the cabin’s back door. It wouldn’t be difficult, and he’d know when to stop.

In his personal darkness, he’s all ears.

“I’d like to speak to you,” the man says.

Tom takes another step. His fingertips touch the rope. He turns to face the house.

He hears the small wheels creak. Imagines weapons in the barrow.

Then he’s moving fast, faster than he’s ever taken this walk before.

“Hey,” the man says.

But Tom is at the back door and knocking five times before the man says another word.

“Tom?”

“Yes. Hurry.”

“Are your—”

“Mom. Hurry.”

Malorie opens the back door and Tom nearly knocks her over as he rushes inside.

“What’s going on?” Olympia asks.

“Mom—” Tom begins.

But there is a knock at the front door.

Malorie: A Bird Box Novel

- Genres: Fiction, Horror, Supernatural Thriller, Suspense, Thriller

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Del Rey

- ISBN-10: 0593156870

- ISBN-13: 9780593156872