Excerpt

Excerpt

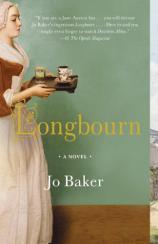

Longbourn

Chapter II

‘Whatever bears affinity to cunning is despicable.’

They were lucky to get him. That was what Mr B. said, as he folded his newspaper and set it aside. What with the War in Spain, and the press of so many able fellows into the Navy; there was, simply put, a dearth of men.

A dearth of men? Lydia repeated the phrase, anxiously searching her sisters’ faces: was this indeed the case? Was England running out of men?

Her father raised his eyes to heaven; Sarah, meanwhile, made big astonished eyes at Mrs Hill: a new servant joining the household! A manservant! Why hadn’t she mentioned it before? Mrs Hill, clutching the coffee pot to her bosom, made big eyes back, and shook her head: shhh! I don’t know, and don’t you dare ask! So Sarah just gave half a nod, clamped her lips shut, and returned her attention to the table, proffering the platter of cold ham: all would come clear in good time, but it did not do to ask. It did not do to speak at all, unless directly addressed. It was best to be deaf as a stone to these conversations, and seem as incapable of forming an opinion on them.

Miss Mary lifted the serving fork and skewered a slice of ham. ‘Papadoesn’t mean your beaux, Lydia – do you, Papa?’

Mr B., leaning out of the way so that Mrs Hill could pour his coffee, said that indeed he did not mean her beaux: Lydia’s beaux always seemed to be in more than plentiful supply. But of working men there was a genuine shortage, which is why he had settled with this lad so promptly – this with an apologetic glance to Mrs Hill, as she moved around him and went to fill his wife’s cup – though the quarter day of Michaelmas was not quite yet upon them, it being the more usual occasion for the hiring and dismissal of servants.

‘You don’t object to this hasty act, I take it, Mrs Hill?’

‘Indeed I am very pleased to hear of it, sir, if he be a decent sort of fellow.’

‘He is, Mrs Hill; I can assure you of that.’

‘Who is he, Papa? Is he from one of the cottages? Do we know the family?’

Mr B. raised his cup before replying. ‘He is a fine upstanding young man, of good family. I had an excellent character of him.’

‘I, for one, am very glad that we will have a nice young man to drive us about,’ said Lydia, ‘for when Mr Hill is perched up there on the carriage box it always looks like we have trained a monkey, shaved him here and there and put him in a hat.’

Mrs Hill stepped away from the table, and set the coffee pot down on the buffet.

‘Lydia!’ Jane and Elizabeth spoke at once.

‘What? He does, you know he does. Just like a spider-monkey, like the one Mrs Long’s sister brought with her from London.’

Mrs Hill looked down at a willow-pattern dish, empty, though crusted round with egg. The three tiny people still crossed their tiny bridge, and the tiny boat crawled like an earwig across the china sea, and all was calm there, and unchanging, and perfect. She breathed. Miss Lydia meant no harm, she never did. And however heedlessly she expressed herself, she was right: this change was certainly to be welcomed. Mr Hill had become, quite suddenly, old. Last winter had been a worrying time: the long drives, the late nights while the ladies danced or played at cards; he had got deeply cold, and had shivered for hours by the fire on his return, his breath rattling in his chest. The coming winter’s balls and parties might have done for him entirely. A nice young man to drive the carriage, and to take up the slack about the house; it could only be to the good.

Mrs Bennet had heard tell, she was now telling her husband and daughters delightedly, of how in the best households they had nothing but manservants waiting on the family and guests, on account of every- one knowing that they cost more in the way of wages, and that there was a high tax to pay on them, because all the fit strong fellows were wanted for the fields and for the war. When it was known that the Bennets now had a smart young man about the place, waiting at table, opening the doors, it would be a thing of great note and marvel in the neighbourhood.

‘I am sure our daughters should be vastly grateful to you, for letting us appear to such advantage, Mr Bennet. You are so considerate. What, pray, is the young fellow’s name?

‘His given name is James,’ Mr Bennet said. ‘The surname is a very common one. He is called Smith.’

‘James Smith.’

It was Mrs Hill who had spoken, barely above her breath, but the words were said. Jane lifted her cup and sipped; Elizabeth raised her eyebrows but stared at her plate; Mrs B. glanced round at her house- keeper. Sarah watched a flush rise up Mrs Hill’s throat; it was all so new and strange that even Mrs Hill had forgot herself for a moment. And then Mr B. swallowed, and cleared his throat, breaking the silence.

‘As I said, a common enough name. I was obliged to act with some celerity in order to secure him, which is why you were not sooner informed, Mrs Hill; I would much rather have consulted you in advance.’

Cheeks pink, the housekeeper bowed her head in acknowledgement.

‘Since the servants’ attics are occupied by your good self, your husband and the housemaids, I have told him he might sleep above the stables. Other than that, I will leave the practical and domestic details to you. He knows he is to defer to you in all things.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ she murmured.

‘Well.’ Mr B. shook out his paper, and retreated behind it. ‘There we are, then. I am glad that it is all settled.’

‘Yes,’ said Mrs B. ‘Are you not always saying, Hill, how you need another pair of hands about the place? This will lighten your load, will it not? This will lighten all your loads.’

Their mistress took in Sarah with a wave of her plump hand, and then, with a flap towards the outer reaches of the house, indicated the rest of the domestic servants: Mr Hill who was hunkered in the kitchen, riddling the fire, and Polly who was, at that moment, thumping down the back stairs with a pile of wet Turkish towels and a scowl.

‘You should be very grateful to Mr Bennet for his thoughtfulness, I am sure.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ said Sarah.

The words, though softly spoken, made Mrs Hill glance across at her; the two of them caught eyes a moment.

‘Thank you, sir,’ said Mrs Hill.

Mrs Bennet dabbed a further spoonful of jam on her remaining piece of buttered muffin, popped it in her mouth, and chewed it twice; she spoke around her mouthful: ‘That’ll be all, Hill.’

Mr B. looked up from his paper at his wife, and then at his housekeeper.

‘Yes, thank you very much, Mrs Hill,’ he said. ‘That will be all for now.’

Longbourn

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction, Historical Romance, Romance

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Vintage

- ISBN-10: 0345806972

- ISBN-13: 9780345806970