Excerpt

Excerpt

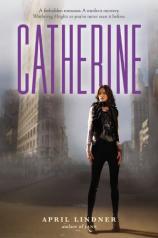

Catherine

Chelsea

As I hurtled toward New York City on a Greyhound bus, I’d

imagined my destination would be a gleaming ultrachic high-rise

or a brownstone full of cousins, aunts, and uncles who would

gather me into their arms, thrilled to discover the long-lost

relative they never knew they had. So the reality was a shock: a

hulking windowless concrete block on the corner of Houston and

Bowery, painted a forbidding black. There wasn’t so much as a

doorbell beside the locked front door. Big jagged silver letters

spelled out the underground. Whatever it was—a restaurant?

a comedy club? a warehouse?—it looked about as welcoming as a

maximum-security prison.

I froze on the front stoop, unsure of what to do next. Had

my mother really grown up here? Two doors down a woman

with fluorescent-yellow hair and a zebra-striped minidress was

arranging thigh-high boots in a boutique window, and a mural of

a fire-snorting dragon on the side of the building vibrated with

color. Though cars blasted past me down the wide street, the side-

walks were surprisingly empty, except for a guy in a long black

apron smoking against a wall and a couple of skaters propelling

their boards in my direction.

Could I have gotten the address wrong? I dug in the front

pocket of my backpack for the letter I’d found last Tuesday, the

letter that had changed everything—my past, my present, my

future. The return address, in my mother’s loopy handwriting,

assured me I was in the right place. I pulled it out and unfolded it,

hoping for some clue I’d managed to miss.

Sweet Chelsea Bell,

By the time you get this letter, I hope you’re old enough to under-

stand and forgive me for leaving. As I write, you’re probably

sleeping in your bed, what’s left of your favorite blue blankie

clutched to your face, and it hurts to think that the next time I

see you you’ll be older, bigger. Maybe you’ll barely remember me.

Maybe your dad is reading this letter to you, or maybe

you’re old enough to read it on your own. Or maybe—if I’m

really lucky—we’ll be together soon and you’ll never need to read

this at all. Still, I’m writing it just in case.

You’re the best daughter I could imagine, better than I

deserve. And your dad’s a good, kind, responsible man. I need

you to know I’m not running away from him. I’m running

toward something. Does that make sense?

I can’t explain exactly why I went away, but here’s the main

thing: I’ve been given a chance to undo the biggest mistake of my

life. That’s why I’ve come back to New York City, to the home I

grew up in. I don’t know yet how long it will take. There are

some people I need to talk to in person. One of them is Jackie,

my best friend from high school. I hope you’ll meet her someday,

because I know she would love you, and I bet you’d feel the same

way about her.

Though I’m far away, everything I see makes me think of

you. Like today, out on the street, I saw a woman in a pink suit

being pulled along the sidewalk by a pack of five identical white

poodles. I know you would have laughed at the sight of her flying

along, her fussy little pink high heels barely touching the ground

as the dogs raced her down the street. You have the greatest

laugh, like lots of bells ringing all at once. At night, when I’m

trying to fall asleep, I close my eyes and I can see your face and

hear that laugh.

Remember me always,

Mom

No matter how many times I read the letter, her words still

sent a jolt through me—an electric current of love, sadness, and

even guilt, because my memories of her had worn away, vanishing

like that tattered blue blanket. All I could summon was warmth,

the tickle of her hair on my face, and the scent of her perfume—

cut grass and little white flowers.

My discovery of the letter had been completely random. I’d

had the day off from slinging crullers at Mr. Donut, but it was the

worst kind of day off, with nothing to do and nobody to do it with.

I finished the last of the mystery novels stacked beside my bed,

and the thought of walking to the library to get more in the

ninety-five-degree heat gave me a headache. My best (and only)

friend, Larissa, was stranded on a family vacation in a part of Cape

Cod so remote it didn’t even have cell-phone service. She’d be gone

for two whole weeks, and though it was pathetic that I had only

one real friend, that’s what moving every couple of years will do to

a person. By the time Dad and I arrived in Marblehead, I’d grown

so tired of starting over that I couldn’t make myself try very hard

to fit in. Luckily, Larissa transferred from private school in the

middle of freshman year, and she was in as dire need of a friend as

I was. But with her out of town, I might as well be a complete

pariah.

I could have used a ride to the beach, but of course my dad was

at his office, teaching. He never used to teach in the summer;

when I was little, he’d take me to the beach or the movies, or even

to his office, where I would spin around in his chair, make long

paper-clip chains, and draw with fluorescent highlighters. But at

some point I got too old to hang around with my dad, and he

started shipping me off to summer camp to be a counselor in

training. This summer I flat out refused to be sent away—I wasn’t

one of those hard-core camp types who lived to make lanyards and

fight color wars. I applied for the job at Mr. Donut so I’d have a

reason to stay home all summer for once.

So I’d gotten my wish, and there I was, hitting refresh at the

Nico Rathburn fansite every fifteen seconds, waiting for someone

else to make a post. When nobody did, forcing me to face the fact

that everyone in the world but me had a life, I decided to look

around in Dad’s closet in search of our old family photos, some-

thing I do every now and then so I won’t forget my mother’s face.

She died when I was three, or so my father had always told me. Of

a brief illness, he would say, to anyone who asked. His face would

go all pale and solemn, and you could tell whoever asked was sorry

they’d brought it up.

I riffled all the way through our box of family photos, and

somehow it still wasn’t enough. Dad’s closet was packed with car-

tons and shoeboxes; there had to be something else interesting in

one of them, but most of what I found was unbelievably pointless.

A stack of old bank statements. A yellowing manuscript from a

textbook Dad had helped edit. Manila envelopes full of tax docu-

ments. I’m not sure why I didn’t give up. I must have been really

bored.

But then I hit the—pun intended—mother lode: a shoebox at

the back of the highest shelf, where I’d never have stumbled on it

by sheer accident. There wasn’t much stuff inside, but all of it was

new to me. My birth certificate. My parents’ marriage license.

Mom’s old passport, stamped in Italy, France, Greece, the Neth-

erlands, and other places too blurry to make out. The next thing I

found set my heart racing: a snapshot of my radiant, glossy-haired

mom in a beret and a man’s flannel shirt. The picture was cut

crookedly in half. She’d been standing beside someone—an old

boyfriend, probably. Part of a hand was still holding hers.

I dug a little deeper and found a few more cut-in-half portraits

of Mom. She looked a lot younger—maybe my age. She was

dressed a lot younger, too; I saw none of the pastel shirts and denim

skirts she’d worn in my baby pictures. Even in a black Pretenders

T-shirt and torn jeans she looked regal and confident in a way that

had unfortunately passed me by, no matter how alike my dad

always said we looked. In another photo she wore a short skirt,

motorcycle boots, and a leather bomber jacket, the missing some-

body’s tan, slender but muscular arm draped across her shoulders.

In that one, she was glancing to the side, toward the person who’d

been chopped out of the picture, her blue eyes laughing.

But the next thing I found blew me away: an envelope

addressed to me, Chelsea Rose Price, care of my dad, Max Price.

Something about the handwriting on the envelope made my heart

beat faster. The blood whooshed in my ears as I read it and the

truth became clear. There hadn’t been a “brief illness.” And Dad

hadn’t sprinkled my mother’s ashes off the coast of Falmouth, the

way he’d said he had.

She hadn’t died at all. She’d run away from us, and he’d been

lying to my face about it for years.

Of all the lies a father could possibly tell his only daughter,

this seemed an especially cruel one—letting me believe my mom

was dead when she wasn’t. But why hadn’t she come home to us,

the way she’d wanted to? Had she changed her mind? Or had Dad

not let her? What else had he been hiding from me?

When I could trust my shaking legs, I ran for my laptop and

typed my mother’s name into Google. I found a Catherine Ever-

sole Price in Des Moines, Iowa. A florist posed beside a prize-

winning arrangement of tropical flowers, she looked nothing like

my mom. One Cathy Eversole turned out to be a fifty-something

real-estate agent in Bakersfield, California, and another was a

fluffy blond newscaster in Indianapolis. On the next page of hits,

I found what I was looking for—a four-year-old story in the North

Shore Ledger.

Woman’s Disappearance Still Unsolved

Ten years since a Danvers wife and mother went miss-

ing, police are no closer to solving the mystery of her

disappearance. On an ordinary weekday, Catherine

Eversole Price vanished from her suburban home with-

out a trace. A wife and mother of a three-year-old

daughter left a brief note saying she had business to

attend to in New York City and would return shortly.

Her husband, Max Price, declined to be interviewed

for this story, but police records show he assumed his

wife had taken a spontaneous trip to her hometown

to visit old acquaintances. Price, at the time a visiting

professor of economics at Harvard, said he thought

his wife would call him from New York and return

home within a day or two.

Letters sent from lower Manhattan reassured

Mr. Price that his wife was safe, and he resolved to wait

patiently for her return. “Cathy always seemed reliable

and sensible. I’m sure Max had no reason to think any-

thing was wrong,” a former neighbor of the couple told

the Ledger. But Price grew alarmed when days passed

without a word, and he went to the police.

An exhaustive search uncovered few leads, and

Price criticized investigators for what he perceived as a

slow and ineffective response to his wife’s disappear-

ance. Now an associate professor of economics at

Salem State College, he resides with his daughter in

Marblehead. A former Danvers neighbor still recalls

seeing Mrs. Price wheel her young daughter’s stroller

through town to the local playground. “Cathy was so

devoted to that little girl of hers. I can’t believe she

went away of her own free will. I’m afraid she must

have met with some kind of foul play.”

A yearlong investigation yielded no leads. “We’ve

done everything in our power to locate Catherine

Price,” County Sheriff Dan Stevenson told the Ledger.

“If a person wants to go missing, New York City is the

perfect place to hide.” He declined to answer questions

about why Mrs. Price might have chosen to run away.

“That’s a private matter,” he told the Ledger.

My heart sped up as my eyes traveled down the screen. So

the county sheriff thought my mom was still alive somewhere in

New York! It seemed at least as likely as any other possibility.

What if all these years she’d been hoping I would figure out the

truth and come find her? Then again, why hadn’t she simply come

to me? If she’d really been alive all this time, and hiding out some-

where, why not call and tell me she was okay?

But maybe she had tried to get in touch. Dad’s job-hopping

and our moving around from one town to the next would have

made it hard for her to track us down. And our phone number

was unlisted (“So students won’t call and wheedle me to change

their grades,” Dad had said). Of course Mom could have found

Dad’s work number online. But what if she hadn’t wanted to talk

to him? What if she knew he was trying to keep me away from

her? He’d kept that letter from me. Plus, the article said my

mother had sent “letters,” which meant there must have been

others.

Unable to sit still a second longer, I paced the house on shaky

legs, every familiar piece of furniture suddenly strange, as though

I’d woken up in somebody else’s life. On the living room book-

shelf, the framed photo of Dad and me goofing around at Wing-

aersheek Beach might as well have been a photo of two strangers.

Who was that man—his blond hair dripping with salt water, his

eyes the same clear green as the ocean sparkling behind us? Some

guy who had been lying to me for fourteen years straight.

At first I rehearsed the speech I was going to give when he got

home, muttering the words as I paced. I would expose him for the

liar he was. How can you live with yourself? Don’t you think it’s time

you told me the truth?

But as soon as I’d figured out exactly what I would say, I real-

ized it was no good. I knew he’d say he’d only been trying to pro-

tect me, and I wasn’t in the mood for his excuses. No: What I

wanted was to get away from him. I wanted to find out the truth

for myself. And more than anything, I wanted my mother.

Dad stayed at his office even later than usual, so I had a long

time to piece together a plan. The first step was obvious: I had to

get to New York City. I would start with the letter’s return

address, knock on the door, and figure out where to go from there.

Luckily, my seventeenth birthday was just a few days away. I knew

Dad would give me a check, the way he’d done since I turned

twelve and stopped wanting Barbie and her Dream House; I guess

after that, he couldn’t figure out what to get me anymore. That

was around the time I quit doing the things he wanted me to—

swim team, piano lessons, and getting straight As—and we

stopped having much of anything to say to each other, to the point

where all he ever wanted to talk about was why I hadn’t made a

list of colleges to apply to and why I didn’t already know what I

wanted to major in. How many times had I heard about my moth-

er’s great sense of purpose and direction, how she’d always known

she wanted to be a writer and go to Harvard, and, sure enough,

she’d applied herself and gotten in? How many times had I asked

myself why I couldn’t be more like my perfect mother?

Well, the joke was on Dad. I was about to become a whole lot

more like my mom. Now I had a purpose—finding her—and a

direction—as far away from him as I could get.

As it turned out, I was right about getting a check for my birthday.

Dad handed me the envelope and stood in the kitchen doorway

waiting for me to rip it open. He was on his way to his office, of

course. He fidgeted in his checked shirt and dorky tie as I read my

card and examined its contents. Five hundred dollars. More than

I’d expected. I should have been glad—after all, I needed the

money—but I couldn’t help feeling let down that it wasn’t some-

thing more personal or fun—an iPhone, maybe, or a boxed DVD

set of The X-Files, something that showed he had thought even the

tiniest bit about what I wanted and who I was.

Even so, as I thanked him and let him kiss me on the cheek, I

felt a twinge of sadness. I knew he would worry about me when

I was gone; he always worried. As I inhaled the familiar scent of

his aftershave, I was seriously tempted to blurt out how I’d found

the letter and give him a chance to explain himself. I opened

my mouth to speak.

But Dad stepped back, took a look at his watch, mumbled

something about being late for work, and bolted. It was my birth-

day, and even so he couldn’t wait to get away from me. I looked

down at the check in my hand and felt the anger flood in again.

Thanks, Dad, I thought. I’ll use this money to buy myself something

you could never give me: a new life not based on lies.

The very next day I slipped out of my house before dawn. That’s

how I came to be stranded in front of 247 Bowery, without a clue

what to do next. Would The Underground eventually open its

doors? And what on earth would I do with myself in the meantime?

I looked around, taking inventory. Across Bowery, well-lit and

glowing like The Underground’s polar opposite, stood a health-

food café. I crossed the street and ducked through the door.

Behind the counter a youngish woman with crayon-red hair and

hennaed hands was manning the juice machine.

I waited my turn, ordered a banana-coconut smoothie, and

asked, “So, that place across the street? Is that some kind of

restaurant?”

She gave me a look as if to say Well, duh. “That’s The Under-

ground. THE Underground.”

“Oh. Right.” Apparently I was supposed to have heard of this

place because, after all, New York is the center of the universe,

and THE Underground is the center of New York. “When does it

open?”

She shrugged. “Different times. Six, maybe. Or seven thirty.”

Great. It was only noon. The guy in line behind me was

breathing down my neck, and I could tell the girl wanted me to

move along, but I had about a thousand questions. “Do you know

who owns it? And how long it’s been there? Like if it’s been there

about fourteen years or more?”

“Of course. It’s been open since the seventies.” She sighed and

turned away from me, firing up the blender and drowning out any

further conversation.

So much for that strategy. If I wanted to learn more about The

Underground, I was going to have to find it out on my own. I took

my smoothie and set up shop at a table in the corner. Luckily, the

place had free WiFi. I googled The Underground and clicked on

the first hit. Punk rock started blaring out of my speakers, drown-

ing out the café’s wind chime-and-synthesizer mood music. One

table over, a lady with floaty gray hair and pink overalls shot me a

dirty look. The website’s jagged silver lettering—just like the let-

tering across the street—told me I’d found the right place.

I plugged in my earbuds and clicked to enter, and a collage

bloomed in front of me—picture upon picture, all of punk rock-

ers. I’d never seen so much leather, so many tattoos and body

piercings and Mohawks in one place. Had my mother grown up in

a punk nightclub? This didn’t mesh with what little I knew about

her—mostly the things my dad had told me. She’d had a 4.0 aver-

age at Harvard before she’d left school to have me. She baked

sourdough bread and made birthday cupcakes from scratch. Most

of all, she’d married my dad, who listened to Bach and Brahms

and whose idea of a wild night was having a glass of red wine

before he dozed off in front of Law & Order reruns.

I examined the evidence in front of me—a sea of unfamiliar

faces sprinkled here and there with one or two I recognized:

Blondie, The Ramones, Green Day. A link took me to The Under-

ground’s history, a formidable block of text in red letters on a

black background. The Underground has outlived its competition—

even the famous CBGB—and remains THE place to catch cutting-

edge underground music. . . .

This was all very interesting, but I was scouting for informa-

tion I could actually use. I found it in the second paragraph.

Visionary founder Jim Eversole . . . Could that be an uncle of mine? I

did the math quickly and realized he was about the right age to

have been my grandfather. After Jim’s untimely death, the torch was

passed briefly to his son, Quentin, who remade the site into an upscale

steak house. But The Underground’s original vision was revived by its

current owner, Hence, former frontman for Riptide. . . .

What kind of name was Hence? Was he a relative of mine,

too? I scanned the screen for my mother’s name but didn’t see it.

No matter. I had a strong feeling I was on the right track. I couldn’t

waste the rest of the afternoon waiting around for The Under-

ground to open. After all, how much time did I have before my

father guessed where I’d run off to and came looking for me? I’d

been careful not to leave any clues. Still, I could imagine Dad

getting home from work, finding me gone, and going on a

frenzied search. How long would it be before he thought to look

for the letter, found it missing, and guessed where I’d gone?

Back at The Underground, I tried pounding on the front door

until my hands ached. Nothing. I walked around to the rear of the

building, stepping over fast-food wrappers and broken beer bot-

tles. I found another door with an actual doorbell beside it. I

pressed it and heard a buzzer ring inside the club. No answer.

I rang again.

Just as I was about to give up, the door opened and I came

face-to-face with a guy exactly my height and slender, with brown

bangs that fell in his eyes and splotches of pink on his cheeks.

We stood for a moment, staring at each other. This couldn’t be

the club’s owner; he was too young—around my age, or a little

older. He wore paint-stained cargo shorts and a faded purple

T-shirt with black letters that read punk’s not dead. Head

cocked questioningly, he looked at me, not saying anything.

He was probably just an employee, but my hopeful side won-

dered if he could be related to me—maybe a long-lost cousin?

“Hello. I’m Chelsea Price.” Would my name mean anything

to him?

It didn’t seem to; his head remained cocked. “We’re not

open yet.”

“I’m looking for the guy who owns this club. Is he here?” When

he didn’t answer, I tried again. “Hence. That’s his name, right?”

“He’ll be in later tonight,” he said, reaching for the door. “I’m

not sure when.” And he started to close the door on me.

“Wait! Please . . .” I could hear my voice getting higher, the way

it does when I get upset. “I took a bus all the way from Massachusetts

to see him. I’ve been dragging this backpack around since five

this morning. . . .”

He hesitated. “I don’t think Hence would like me to let you in.”

But something about his hesitation gave me hope. I leaned

forward a little, so that to close the door he’d have to slam it in my

face. “My pack is heavy,” I said. “And it’s so hot out.”

The guy sighed, but he didn’t shut the door on me. “You want

to fill out an application? I’ll give it to him when he gets in. . . .”

“No! I’m not here for a job. I’m looking for my mother, Cath-

erine Eversole.”

The expression on his face changed.

“You’ve heard of her?”

His response was tight-lipped. “I know the name.”

“You do?” I asked. “Is she related to the guy who founded the

club? She’s his daughter, isn’t she?” I was pretty pleased with

myself for having figured this out, but he didn’t answer. Still, he

swung the door open and let me in.

I followed him down a long hallway that reeked of fresh paint.

We passed a door that led into an industrial-looking kitchen and

another that opened into a room stacked high with mixers and

musical equipment, its walls smeared with graffiti. So this was

what a nightclub looked like.

“This way.” He opened another door and flipped on a light

switch, illuminating a steep staircase to the basement. I followed

him down the creaky steps. At the bottom he clicked on a bare

lightbulb dangling by its wire from the ceiling.

The basement’s floor and walls were stark cement, adorned

only by a poster of some band I’d never heard of called Black

Watch—three bare-chested guys in eyeliner and tartan plaid

pants. A metal cot was covered with a few scratchy-looking blan-

kets and a lumpy pillow. Against the foot of the bed leaned a bat-

tered electric guitar. “You can stay here until Hence gets in.” He

turned to leave.

“Is this where you sleep?” I asked his retreating back, not

wanting to be left alone for God knows how long. “Wait!”

He paused. Before he could disappear again, I asked, “What’s

your name, anyway?”

“Cooper,” he said. “Coop.”

“Are you Hence’s son?”

He laughed, as though I’d said something funny. “No. I work

here. And I need to get some painting done. I’ll let you know when

Hence gets home.” He took the stairs away from me two at a time.

When he was out of earshot, I allowed myself a heavy sigh. I

perched on the cot’s crinkly mattress, with nothing to do but wait.

The small, ancient TV in the corner got about four stations, all of

them too staticky to watch. I thought of the phone in my pocket,

but I couldn’t exactly call anyone. Larissa was still on the Cape,

and even if she hadn’t been, I couldn’t trust her not to crack under

my father’s interrogation.

After at least an hour had passed and I was about to die of bore-

dom, I started poking around Cooper’s stuff. Not that there was

much of it—a heavy English lit textbook under his cot, and a bat-

tered trunk plastered with stickers and stuffed with a tangle of jeans

and T-shirts with names of bands I’d never heard of. I fought the

urge to fold his clothes for him—that would have just been weird.

Instead, I picked up his electric guitar, slung the strap over my

shoulder, and stood in rock-star stance, giving it a strum. Not that

I knew how to play. Those piano lessons Dad had forced me to

take revealed I wasn’t the prodigy he’d hoped for, and in a few

months he’d gotten tired of nagging me to practice. Now, wonder-

ing if my mother had been musical, I ruffled my hair and drew my

lip back in a sneer, trying to look like the pictures on The Under-

ground’s website. I gave one last muffled, tuneless strum. Accord-

ing to my watch, it was five thirty. What if Cooper forgot his

promise to come and get me? Would I have to stay trapped in this

basement all night?

And then I started worrying about Hence. Cooper had seemed

nervous about my being here, like his boss would bite his head off

for letting me in. Why else would he be hiding me in the basement?

But if I really was the granddaughter of the guy who founded The

Underground, didn’t that make me something like rock-and-roll

royalty? Why wouldn’t the current owner be happy to meet me?

Suddenly tired, I thought about lying down on the cot, maybe

crawling under the blankets, but they smelled like boy and proba-

bly hadn’t been washed in months. Instead, I dug into my back-

pack, zipped on a hoodie for warmth, and put a T-shirt between

my head and the grungy-looking pillow. Earbuds in, I hit play on

my iPod and shut my eyes.

When I opened them again, groggy and disoriented, someone

was standing over me, watching me sleep. I bolted upright, strug-

gling to recall where I was. The someone was a guy, familiar and

strange at the same time, looking down at me with a wry little

smile, like I was a puzzle he was working out how to solve. I yelped,

scrambling to my feet, and our heads collided.

“Ouch!” The pain jolted me back to the present, and I remem-

bered where I was and how I’d gotten there. “Geez! What were

you looking at?” It didn’t seem fair, watching a person like that

while she slept.

“I came to get you.” The flush on his cheeks deepened. “I was

trying to decide whether I should wake you up.”

“You scared the crap out of me.” I didn’t mean to be rude, but

I’d always been cursed with a tendency to blurt out the first thing

that pops into my head. It was something I’d been meaning to

work on.

“Sorry.” The flush on his cheeks deepened.

I felt bad for snapping at him, so I changed the subject. “Any-

way, is Hence here?”

Cooper nodded. “He’s not in the best mood.”

I shook the hair out of my eyes and slipped my hand into my

hoodie pocket to make sure the letter was still safely there. “That’s

okay. Neither am I.”

“No, seriously. He can be prickly. It’s easy to get on his bad

side.” He paused to look me squarely in the face with eyes that

were midway between blue and green. “And I’m guessing you can

be prickly yourself.”

True as that was, I didn’t much like hearing it from a complete

stranger. “I’m not prickly.” I drew myself up to my full height.

“And I’m not afraid of your boss.” Because, really, how bad could

this Hence character be?

“Hokay.” Cooper’s mouth twitched, like he was holding back a

grin. “Don’t say I didn’t warn you.” And with that he led me up the

creaking staircase, into the heart of The Underground.

~

Catherine

My life changed forever on an ordinary Tuesday. I was rushing

home from school so I could get together with Jackie and start on

our homework assignment. The school year had barely begun, and

already I was feeling frazzled and more than a little frustrated—I

wanted to be doing my own writing, not some lame collaborative

book report. It was a hot, sticky afternoon, the kind of late-summer

day that made me want to hang out in a sidewalk café with an iced

tea and a fresh pad of paper, eavesdropping on the conversations

around me and jotting down every crazy idea that popped into my

head. It felt wrong to be wearing an itchy school uniform and lug-

ging a backpack, and even more wrong to have homework.

When I took the corner, I saw him right away: a slender guy

with shaggy black hair camped out on my front stoop next to a

guitar case and a big duffel bag. My first thought was Oh, no, not

another one. One of the most annoying things about living above a

nightclub—and believe me, there are plenty—is the musicians

who are always trying to introduce themselves to my dad, hoping

to convince him to put them on the bill. It’s a waste of time, of

course; Dad books his acts a year in advance, and he knows exactly

who he will and won’t let play in the club. A band not only has to

be great, it has to be on its way up, about to go national. “The

Underground has to stay relevant. We’re more than a place to hear

music. We’re tastemakers”—that’s how he puts it. He’s not exactly

humble when it comes to The Underground, but why should he

be? The place is kind of famous, and Dad’s a legend in the rock-

and-roll world. Or so everybody has told me all my life, to the

point where I get a little tired of hearing about it.

Really, I’d gotten so sick of coming home and finding stray

guitar-god wannabes on the doorstep that I was thinking about

sneaking around to the back door so I wouldn’t have to talk with

this one. He was staring down at his feet—lime-green Chuck

Taylor All Stars—so I could have slipped right around the build-

ing without him so much as noticing me, except he happened to

glance up as I was passing, and the look on his face stopped me.

He was striking, with dark eyes, glossy hair, skin like coffee with

extra cream, and the sharpest cheekbones I’d ever seen, but it was

more than that. He looked hungry. Literally. Like he hadn’t eaten

in days. I had this feeling he needed someone to be kind to him. It

was written all over his face: He was on the verge of losing hope,

and he needed someone to urge him to keep going, to fight for

what he wanted.

It was the strangest thing. It’s not like I’m usually good at reading minds.

If anything, I’m the opposite—dense about what other

people are thinking and feeling. But something flashed between

me and the guy on the stoop—a kind of understanding. So I went

over to him and he scrambled to his feet and dusted his hands off

on his jeans. He held out his hand and I shook it—like we were

executives meeting at a business luncheon. His touch surprised

me; the palm of his hand was dry but hot—almost feverish.

“Do you work here?” His voice sounded hopeful, but right

away his gaze shot back down to his sneakers, as if he didn’t dare

meet my eyes for long.

It was a strange question, considering I was wearing my school

uniform and carrying a knapsack.

“I live here.” I threw my shoulders back and brushed a stray

lock of hair from my eyes.

“You live in The Underground?” Now he was looking at me in

disbelief, as though I’d claimed I lived in the Taj Mahal or Buck-

ingham Palace.

“Not in it. Above it.” I fumbled in my knapsack for my keys.

“My father owns the place.”

“Seriously? You’re Jim Eversole’s daughter?”

I had to hand it to him; he’d done his homework. But the hope

in his voice made my stomach lurch. Like all the others, this one

would turn out to be way more interested in my father than in me.

Why had I thought, even for a moment, that there might be more

to him?

“You want Dad to book you.” It wasn’t a question.

“That’s not why I’m here.” He sounded defensive. “I know I’m

not ready for that yet. For now, I just want a job. Any job. Waiting

tables, maybe.” From closer up, I could see the faint scruff above

his upper lip and along his chin. Despite the heat, he had on a

black denim jacket, and under it his faded blue T-shirt was speck-

led with small holes, one wash away from dissolving into shreds.

“I don’t think my dad needs any more waiters.”

“I’ll wash floors. I’ll even scrub toilets. I just want to get to

know the place from the inside.” He dug his hands into his front

pockets and looked back down at his sneakers, as if he knew

he was asking for a huge favor and didn’t want to pressure me one

way or another.

Maybe he wasn’t like the others who had tried to worm their

way into The Underground. I paused a moment, weighing my

options. When I opened the door, stepped inside, and beckoned

for him to follow, I wondered if I was making a big mistake.

I usually hate giving tours of the club to my friends. Call me para-

noid, but I get the feeling that where I live is more important

to most people than who I am. But showing this guy around made

me see the place through new eyes. First I took him through the

main room. As we approached the stage, he paused for a long

moment, staring like he could see the ghosts of all the acts who’d

played there. So I waited beside him, recalling some of the bands

I’d seen—The Magnetics, The Faithful, and Hot Jones Sundae

were a few of my recent favorites—and I had the feeling that if I

grabbed his hand and squeezed my eyes shut I could share my

memories so that he’d have them, too.

But I didn’t. What would he have thought if I’d tried it? Most

likely that I was crazy—or hitting on him.

Instead, I cleared my throat and led him onward, into the

mixing room with its tangle of wires and crates. I let him take a

peek at Dad’s office, and at his wall of glossy photographs of

bands who’d come through the club. I saved my favorite spot for

last: the dressing room where so many rockers had graffitied the

walls into a multilayered, psychedelic mess. I pointed out a doodle

drawn by Joey Ramone, and he studied it closely, as though trying

to decipher its secret meaning.

“Thanks,” he said when the tour was over. “For letting me take

up your time. And for giving me a tour.”

I shrugged. “No problem.” There was nothing more to show

him, really, but I wasn’t ready to head upstairs and start dinner

just yet. “I’m Catherine.” And when he didn’t reply, I said, “You

have a name, right?”

“Hence.”

It took me a while to wrap my mind around that one. “Hans?”

His answer came through gritted teeth, like he’d been asked

that question a thousand times. “Hence. Like therefore.”

I wanted to ask him if it was short for anything, and whether

he had a last name, and where he’d come from, but he crossed his

arms over his chest and cast a glance toward the front of the

building. I got the distinct sense he was about to bolt. “You want

to leave a phone number? In case my dad wants to get in touch

with you? If he’s hiring?”

Hence grimaced again. “I don’t have a phone,” he said. “I’m not

really staying anywhere. I’m . . . I’m looking for someplace.” He

swallowed hard and I remembered the impression I’d had earlier,

that he was on the verge of giving up. Had he been sleeping on the

streets? Or in a shelter?

So I did something I probably shouldn’t have. I invited him up

to our apartment, into the kitchen. At my urging he sat down on

one of the stools along the counter, perched uneasily like a stray cat

who wasn’t sure if he was going to be stroked or shooed. I cooked

him one of those make-it-yourself pizzas heaped with everything

I could find in the fridge. He practically swallowed it whole, so I

made him another. Either he wasn’t much of a talker or he was too

busy eating to make chitchat. To fill the silence, I talked about

myself—about how I wished I were musical but couldn’t carry a

tune in a bucket, so I wrote poetry instead, and how most of the

girls at school thought I was weird because I liked vintage clothes

and would rather spend an afternoon reading than shopping. I went

on and on until I noticed I was whining about my relatively nice life

to a guy who probably didn’t even have a roof to sleep under.

The realization brought a blush to my cheeks.

“No,” Hence said, frowning down at his plate. “Keep going.

I’m interested.”

“I’d like to hear about you.” I stole a glance at the kitchen clock.

It was 4:15, and Dad had told me that morning to expect him home

at about five. My father’s pretty cool about most things, but even so

I didn’t want him to come home and find me alone with a boy

whose last name I didn’t even know. Same thing goes for my

brother, Quentin, who was due back from school any minute, and

who could be a bit overprotective and big-brothery sometimes.

“There’s nothing to tell,” Hence said. “I’ve always wanted to

come to New York to see The Underground. I’ve read about the

seventies punk scene, and the place is legendary. . . . But you know

that already.” And he stopped, as though that’s all I could possibly

have needed to know about him.

If I hadn’t been worried about the time, I would have pressed

further. I needed to get him safely outside, but I didn’t want to

let him disappear into the night, not before I at least tried to help

him. I reached out—slowly, so I wouldn’t startle him—and tugged

his jacket sleeve. “I have an idea.”

I sent Hence out, telling him to return around six thirty. Less

than ten minutes later, Quentin burst through the front door

without so much as a hello. A bag of fast food in his arms, he took

the stairs up to his room two at a time and locked the door behind

him. Q had been cranky a lot lately and, judging by the expression

on his face as he blew past me, that night was no exception. Good

thing I’d gotten Hence out in time.

Twenty minutes later Dad turned up, and—surprise, surprise—

he was in a bad mood, too, after a long, frustrating meeting with

his investment broker. He lumbered into the kitchen, kissed

me on the cheek, loosened his tie, and tossed his jacket over a

chair.

“I started a nightclub so I’d never have to deal with money-

grubbers again, and look at me now.” He opened the refrigerator

and stared absently at the shelves as if something delicious would

magically appear in front of him. “Completely at their mercy.”

“I’m making pizza,” I told him. “Pepperoni and mushroom.

Your favorite. I’ll have it ready in ten minutes if you’ll sit down and

get out of my way.”

He grabbed a can of club soda and shut the door. “I don’t

deserve you, Cupcake.” Dad had called me that for as long as I

could remember, and despite being too old for it I didn’t have the

heart to make him stop. Though he was busy almost all the time and

could be a bit distracted, he still had the softest heart imaginable.

While I cut the pizza and shoveled slice after slice onto his

plate, I told him about the nice guy who had come to the club look-

ing for a job as a busboy or janitor because he’d read books about

The Underground and wanted to see it for himself. Of course, Dad

wasn’t a total pushover. He took hiring very seriously, so I made

a big point of saying how trustworthy Hence seemed, and how

honored he would be to work even the most menial job, to the

point where I was worried I was laying it on too thick, but Dad just

kept nodding, with that faraway look that meant he was either lis-

tening thoughtfully or musing about something else completely.

Luckily, it turned out he was listening, and by the time Hence

knocked on the front door, Dad was completely primed. After

introducing the two of them, I ducked into the hallway and hov-

ered nearby, ready to pretend I was on my way upstairs if Dad

noticed me. All Hence had to do was shake hands and talk music,

and the job of busboy/janitor was his. The other part was trickier.

Hence thanked Dad, then looked so uncomfortable I started to

worry he’d get all the way out the door without mentioning he had

no place to sleep. Finally, I couldn’t stand it anymore: I stuck my

head into the club and gave him a pointed look.

“There’s one other thing, sir. . . .” he began.

“Sir? I’m not royalty, Hence. Call me Jim, the way everybody

else does.”

“I don’t have any place to sleep, Jim,” Hence blurted out. “Can

you, um, recommend a place nearby—a hostel, maybe, or a board-

ing house?”

Dad did just what I hoped he’d do—he said if Hence was will-

ing to clean out the basement, he could stay here. We’d taken in

stray musicians before, so I had a feeling he’d be cool about it, and

I was right. Before long, Hence, his guitar, and his duffel bag

were in the basement. I would have slipped downstairs to say con-

gratulations and help him shift crates around and set up the metal

folding cot, but as Dad helped me load the dishwasher, he seemed

to be watching me more closely than usual.

“Why are you so interested in this boy, Cathy?” he finally

asked, a bemused smile on his lips. “It’s not like he’s the first ragtag

guitarist to come knocking on our door.”

“He’s so intense. I feel like he wants the job more than any of

the others did.” I paused. “Plus, he desperately needs our help,

don’t you think?”

Dad threw an arm around my shoulders, squeezed, and kissed

the top of my head. “That’s my Cupcake,” he said. “Kind to a fault.”

Satisfied, he let the subject drop, eager to settle into his favorite

armchair with the day’s newspapers and to let me go off and do my

homework.

Another father might have hesitated to let a good-looking

stranger move in under his roof. As I rearranged my backpack,

emptying out the heavy books I wouldn’t need to lug all the way

over to Jackie’s, I thought about how great my dad was—and how

much he trusted me. What intrigued me about Hence wasn’t his

good looks—I’d been burned by one too many gorgeous musi-

cians. It was his intensity—that dark hunger in his eyes—coupled

with that hurt look of his, the way he had of averting his glance as

though he’d been kicked hard by someone he trusted and didn’t

dare let down his guard. I knew he must have stories to tell about

the past he was fleeing and the future he’d planned for himself.

I’ve always liked mysteries, and now one had landed on my door-

step, just begging to be solved.