Excerpt

Excerpt

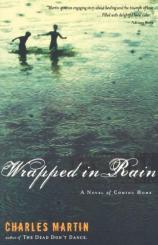

Wrapped in Rain: A Novel of Coming Home

Chapter One

Maybe it's the July showers that appear at 3:00 p.m., regular as sunshine, maybe it's the September hurricanes that cut a swath across the Atlantic and then dump their guts at landfall, or maybe it's just God crying on Florida, but whatever it is, and however it works, the St. Johns River is and always has been the soul of Florida.

It collects in the mist, south of Osceola, and then unlike most every other river in the world, except the Nile, it winds northward, swelling as it flows. Overflowing at Lake George, underground rivers crack crystal springs in the earth's crust and send it sailing farther northward where it gives rise to commerce, trade, million-dollar homes, and Jacksonville--once commonly referred to as Cowford--because that's where the cows forded the river.

South of Jacksonville, the river's waist bulges to three miles wide, sparking little spurs or creeks peopled by barnacled marinas and long-established fish camps where the people are good and most of their stories are as winding as the river. A few miles south and east of the naval air station--headquarters to several squadrons of the huge, droning, four-propeller P-3 Orion--Julington Creek is a small bulge in the waistband that turns east out of the river, dips under State Road 13, winds beneath a canopy of majestic oaks, and disappears into the muck of a virgin Florida landscape.

On the south bank of Julington Creek, surrounded by rows of orange and grapefruit trees, Spiraling Oaks Mental Health Facility occupies a little more than ten acres of black, rich, organic, worm-crawling dirt. If decay has a smell, this is it. It's shaded by sprawling live oak trees whose limbs twist upward like arms and outward like tentacles, the tips of which are heavily laden with ten million acorns horded by fat, noisy, scurrying squirrels wary of hawks, owls, and ospreys.

Spiraling Oaks is where people go, or are sent, when their families don't know what else to do with them. If there's a precipice to insanity, this is it. It's the last stop before the nuthouse, although in truth, it is just that.

By 10:00 a.m., the morning shift had changed, but not before administering the required doses of Zoloft, Zyprexa, Lithium, Prozac, Respidol, Haldol, Prolixen, Thorazine, Selaxa, Paxil, or Depakote to all forty-seven patients. Lithium was the staple, the base ingredient in all their diets, as all but two patients had blood levels in the therapeutic range. The other two were new admissions and soon to follow. This practice gave rise to its nickname--Lithiumville--which was funny to everyone but the patients. More than half the patients were taking a morning cocktail of lithium plus one. About a quarter of the patients, the more serious cases, were swallowing lithium plus two. Only a handful were ingesting lithium plus three. These were the lifers. The go-figures. The no-hopers. The why-were-they-borns.

The campus buildings were all one story. That way, none of the patients could step out of a second-story window. The main patient building, Wagemaker Hall, formed a semicircle with several nurses' stations spaced strategically six rooms apart. Tiled floors, scenically painted rooms, soft music, and cheerful employees. The whole place smelled like a deep-muscle rub--soothing and aromatic.

The patient in room 1 was a two-year occupant and at fifty-two, a veteran of three such facilities. Known as "the computer man," he was once a rather gifted programmer, responsible for high-security government mainframes. But all that programming had gone to his head, because he now believed he had a computer inside of him that told him what to do and where to go. He was excitable, hyper, and often needed staff assistance to navigate the halls, eat, or find the bathroom--which he seldom did in time or in the appropriate place. That fact alone explained the smell. He fluctuated between climbing the walls and being catatonic. There was no in-between and had not been in some time. He was either up or down. On or off. Yes or no. He had not spoken in at least a year, his face often frozen in a grimace and his body held in odd postures--evidence of the internal conversation occurring inside the shell of a man who once had an IQ of 186 or greater. Chances were quite good that he'd leave Spiraling Oaks strapped to a stretcher and carrying a one-way ticket to a downtown facility where all the doors led in and all the rooms were decorated with blue, four-inch padding.

The patient in room two was female, twenty-seven, relatively new, and currently asleep under a rather potent dose of 1,200 milligrams of Thorazine. She would pose no problem today, tomorrow, or, for that matter, through the weekend. Neither would the psychotic tendencies that slept under the same sedation. Three days ago her husband had knocked on the front door and asked to admit her. This occurred shortly after her mania, and nineteenth grandiose scheme, had emptied their bank account and given $67,000 in cash to a man who claimed to have created a gizmo that doubled the gas mileage in every car on earth. The stranger gave no receipt and, like the money, was never seen again.

The patient in room 3 had turned forty-eight several times in his three years here and now stood at the nurses' counter and asked, "What time does the Zest begin?" When the nurse didn't respond, he pounded the desk and said, "The ship has come and I'm going nowhere. If you tell God, I'll die." When she just smiled, he started pacing back and forth, mumbling to himself. His speech was pressured, his mind was racing through a thousand brilliant ideas a second, and his stomach was growling because, convinced his stomach was in hell, he hadn't eaten in three days. He was euphoric, hallucinating with detail, and about five seconds from his next glass of cranberry juice--the nurses' syringe of choice.

By 10:15 a.m., the thirty-three-year-old patient in room 6 had not eaten his applesauce. Instead, he peered from around the bathroom door and eyed it with suspicion. He had been here seven years and was the last of the lithium-plus-three patients. He knew about the lithium, Tegretol, and Depakote, but he couldn't quite figure out where they were putting the 100 milligrams of Thorazine twice a day. He knew they were putting it somewhere, but in the last few months he had simply been too continually groggy to know where. After seven years in room 6, the staff here could pretty well predict that he would cycle seven to eight times a year. During those times, the patient had responded best to stepped-down doses of Thorazine over a two-week period. This had been explained to the patient several times, and he understood this, but that didn't mean he liked it. He fit in well, although at thirty-three, he was much younger than the median age of forty-seven. His dark hair was thinning and receding, and a few gray hairs now surfaced around his ears. To hide the gray, but not the balding and the recession, he kept it cropped pretty close. This trait was unlike his brother, Tucker, whom the patient had not seen since he dropped him off at the front door seven years ago.

Matthew Mason got his nickname in second grade when, on the first day of class, he wrote his name in cursive. Miss Ella had been working with him at the kitchen table, and he was only too proud to show his teacher that he knew his cursive letters. His only problem was that on this particular day, he didn't close the loop on the top of the a. So instead of an a, the teacher read u and the name stuck. So did the laughter, finger-pointing, and snickering. Ever since, he'd been Mutt Mason.

His olive skin made him think his mother was either Spanish or Mexican. But it was anybody's guess. His father was a squatty, fat man with fair skin and a tendency for skin moles. Mutt had those too. He looked from the tray to the bathroom mirror and noticed how his once well-fitting clothes looked baggy and hung one size too big. He studied his shoulders and asked himself if he had shrunk in his time here, the seventh time he had asked that question today. Although he had put on three pounds in the last year, he was down from his preadmission weight of 175 pounds. His Popeye forearms, once bulging with strength and hammer-wielding power, were now taut and sinewy. Currently, he was 162 pounds--his exact weight on the day they buried Miss Ella. His dark eyes and eyebrows matched his skin--reminding him that he once tanned easily. Now, fluorescent lights were the extent of his UV exposure.

His hands had weakened and the calluses long since gone soft. The sweaty young boy who once arm-climbed the rope to the top of the water tower or rode one-handed down the zip line no longer looked back at him in the mirror. He liked the water, liked the view from the tower, liked the thrill of the fall as the zip handle caught and flung him forward, liked the sound of the windmill as it sucked water up the two-inch pipe from the quarry and filled the pool-like bowl standing some twenty feet off the ground. He thought of Tucker and his water-green eyes. He listened for Tucker's quiet voice and tender confidence, but of all the voices in his head, Tucker's was not among them.

He thought of the barn, of hitting chert rocks with a splintery wooden bat, and of how, as Tucker got older, the back wall of the barn looked like Swiss cheese. He thought of swimming in the quarry, eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on the back porch with Miss Ella, running through the shoulder-height hay at daylight, and climbing onto the roof of Waverly Hall under a cloudless, moonlit night just to peek at the world around him. The thought of that place brought a smile to his face--which was odd given its history.

He thought of the massive stone-and-brick walls, the weeping mortar that held them together and spilled out the cracks between the two; the black slate tiles stacked like fish scales one atop the other on the roof; the gargoyles on the turrets that spouted water when it rained, and the copper gutters that hugged the house like exhaust pipes; he thought of the oak front door that was four inches thick and the brass door knocker that looked like a lion's face and took two hands to lift, the tall ceilings filled with old art and four rows of crown molding, the shelves of leather-bound books in the library that no one had ever read, and the ladder on wheels that rolled from one shelf to the next; he thought of the hollow sound of shoes on the tiled and marbled floors, the dining room table inlaid with gold that seated thirteen people on each side, and the rug beneath it that took a family of seven twenty-eight years to weave; he thought of the chimney sweeps that nested in the attic where he kept his toys, and then he thought of the rats in the basement where Rex kept his; he thought of the crystal chandelier hanging in the foyer that was as big around as the hood of a Cadillac, the grandfather clock that was always five minutes too fast and shook the walls when it chimed each morning at seven, and the bunk beds where he and Tucker fought alligators, Indians, Captain Hook, and nightmares; he thought of the long, winding stairs and the four-second slide down the wide, smooth railing, the smell and heat from the kitchen, and how his heart never left hungry; and then he thought of the sound of Miss Ella humming as she polished one of three silver sets, scrubbed the mahogany floors on her knees, or washed the windows that framed his world.

Finally, he thought of that angry night, and the smile left his face. He thought of the months that followed, of Rex's distance and, for all practical purposes, disappearance. He thought of his own many years alone when he found safety amid the loneliness inside abandoned train cars rattling up and down the East Coast. Then he thought of the funeral, the long, quiet drive from Alabama, and the way Tucker walked off without ever saying good-bye.

No description fit. Although abandoned got close. Rex had driven a permanent, intangible wedge between them, and it cut deeper than anyone cared to admit. In spite of Miss Ella's hopes, hugs, sermonettes, and callused knees, the blade, bloody and two-edged, proved too much, the pain too intertwined. He and Tucker had retreated, buried the memory, and in time, each other. Rex had won.

In one of her front-porch sermons spoken from the pulpit of her rocker, Miss Ella had told him that if anger ever took root, it latched on, dug in, and choked the life out of whatever heart was carrying it. Turned out she was right, because now the vines were forearm-thick and formed an inflexible patchwork around his heart. Tucker's too. Mutt's was bad, but maybe Tuck's was the worst. Like a hundred-year-old wisteria, the vine had split the rock that once protected it.

During his first six months at Spiraling Oaks, Mutt had responded so poorly to medication that his doctor prescribed and administered ECT--electroconvulsive therapy. As the name implies, patients are sedated, given a muscle relaxer to prevent injury during convulsion, and then shocked until their toes curl, their eyes roll back, and they pee in their pants. Supposedly, it works faster than medication, but in Mutt's case, some hurts live deeper than electricity can shock out.

This was why Mutt eyed his applesauce. He had no desire to be strapped with electrodes and have a catheter shoved up his penis, but at this stage his paranoia had run rampant and there were only two venues left for them to sneak the medicine into his system: applesauce in the morning and chocolate pudding at night. They knew he enjoyed both, so compliance had never been a problem. Until now.

Someone had dolloped the applesauce into a small Styrofoam cup on the corner of his tray and sprinkled a swirl of cinnamon into it. Except the cinnamon wasn't all on top. He glanced upward and sideways. Vicki, his long-legged nurse with Spanish eyes, long jet-black hair, short skirts, and a knack for chess, would be in here soon waving a spoon in front of his face and whispering, "Mutt, eat up."

Mutt grew up growing his own apples and making his own applesauce--a childhood favorite--with Miss Ella every fall, but she didn't use the same ingredients. She pureed the apples, sometimes mixing in canned peaches they had put away that summer and maybe even a little cinnamon or vanilla extract, but she left out the secret ingredient now hidden beneath the cinnamon swirl. He liked Miss Ella's better.

From his bedroom window, Mutt could see three prominent landmarks: Julington Creek, the Julington Creek Marina, and the back porch of Clark's Fish Camp. If he leaned far enough out the window, he could see the St. Johns. On several occasions, the staff had rented Gheenoes--sort of a canoe with a square stern that was impossible to overturn or sink. They'd launch from the marina and take patients on early afternoon strolls up the creek only to return the boats to the marina owner who affectionately referred to his across-the-creek neighbors as a "dang-sure bona fide nuthouse!"

With one eye walking around the rim of the Styrofoam cup, Mutt glanced outside and admitted that in seven years, he'd heard and watched a lot of acorns fall. "Millions," he muttered to himself as another one bounced off the windowsill and sent a nearby squirrel chattering through the grass, tail raised high. Lucidity was fleeting, a by-product of the pills. But so was the silence. And at one point, he'd have done anything, or let them do anything to him, to quiet the ruckus in his head.

He looked around and noted with satisfaction that his room was not padded. He wasn't that far gone. That meant there was still hope. Being here didn't mean he couldn't reason. Being crazy didn't make him stupid. Nor did it make him Rain Man. He could reason just fine; it's just that his reasoning took a bit more circuitous route than that of others, and he didn't always land on the same conclusion.

Unlike the other patients, no one had to tell him he was standing on the ledge. He had felt his toes reach out over the rock's end long ago. The chasm was deep, and riding around was not an option. There was only one way across. The patients here could look down into the chasm and they could look back, but getting across meant they had to sprout wings and jump a long, long way. Most would never do it. Too painful. Too uncertain. Too many steps had to be untaken or taken back. Mutt knew this too.

There was really only one way out of here alive--strapped down tight in the back of an ambulance and swimming in Thorazine. Mutt had never seen anyone leave through the front door who was not tied like Gulliver to a stretcher. He always listened for the beeps, the paramedics' hard heels clicking on the tiled floors, the stretcher wheels clickety-clacking over the grout, and the doors sliding open and shut every time somebody was rolled down the hall and signed out, and then the sirens as they sped away under the stoplights. Mutt wouldn't let that happen to himself for two reasons. First, he didn't like the noise from the sirens. It gave him a headache. And second, he'd miss his only true friend, Gibby.

Gibby, known in the national medical community as Dr. Gilbert Wagemaker, was a seventy-one-year-young psychiatrist with long, stringy white hair to his shoulders, ambling legs, big and round Coke-bottle glasses often tilted to one side, dirty fingernails that were always too long, and sandals that exposed his crooked toes. Aside from his work, he had an affinity for fly-fishing. In truth, it was his own addiction. If it weren't for his name tag and white coat, he might be mistaken for a patient, but in reality--which is where Gibby hoped to bring most of his patients--he was the sole reason most of the patients hadn't been carted out the front door by the paramedics.

Seventeen years ago, a disgruntled nurse hung a jagged piece of yellow steno paper on his door and hastily scribbled, "Quack doctor." Gibby saw it, took off his glasses, chewed on the earpiece, and studied the note. After a thorough inspection, he smiled, nodded, and walked into his office. A few days later he had it framed. It had been there ever since.

Last year he had been given a lifetime achievement award by a national society of twelve hundred other quack doctors. In his acceptance speech, he referred to his patients and said, "Sometimes I'm not sure who's more crazy, me or them." When the laughter quieted, he said, "Admittedly, it takes one to know one." When pressed about his use of ECT in specific cases, he responded, "Son, it doesn't make much sense to allow a psychotic to remain psychotic simply because you are unwilling to force the issue of either ECT, medication, or their benefits. The proof is in the pudding, and if you get to Spiraling Oaks, I'll serve you a dish." Despite his controversial remedies and what some considered forty years of overmedicating, Gibby had a remarkable track record of returning the worst of the worst to an almost level playing field. He had seen fathers return to their children, husbands return to their wives, and children return to their parents. But the success stories weren't enough. The halls were still full. So Gibby returned to work. Often with a 6-weight fly rod in one hand.

Gibby was one of two reasons that Matthew Mason was still alive and ticking--albeit sporadically. The other was the collective memory of Miss Ella Rain. Since his admission seven years, four months, and eighteen days ago, Gibby had taken Mutt's case personally. Something he shouldn't have done professionally, and yet personally, he had.

For Mutt, the voices came and went. But mostly, they came. As he watched the creek crest at 10:17 a.m., the voices were tuning up. He knew the applesauce would quiet them, but for the last year, he had been trying to get his courage up to skip his morning dessert. "Maybe today," he said as a Ski Nautique pulling a wake boarder and two teenagers on Jet Skis flew down the creek toward the river. Soon thereafter they were followed by a white Gheenoe almost sixteen feet long and powered by a small fifteen-horse outboard skimming across the top of the water. Mutt focused on the picture of the Gheenoe--the fishing poles leaning over the side, the red-and-white bait bucket, the trolling motor, and the two young boys wrapped in orange life jackets.

At probably twenty knots, the wind pulled at their shirts and jackets but not their hair because their baseball caps were pulled down tight, pushing on their ears and almost hiding their crew cuts. The father sat in back, one hand on the throttle, the other resting on the side of the boat, watching the water, the bow, and his boys. He eased off on the throttle, turned toward shore, and searched the lily pads for an open hole or a break large enough to drop their worms, beetlespins, and broken-back Rapalas. Mutt watched them as they passed beneath his window, sending their small wake up through grass and cypress stumps. After they were gone, the sound had faded, and the water stilled, Mutt sat on the edge of his bed and considered the look on their faces. The thing that puzzled him was not what they did show, but rather what they didn't. No fear and no anger.

Mutt knew the drugs only narcotized him, quieted the chorus, and numbed the pain, but they did little to address the root problem. Even in his present state, Mutt knew the drugs would not and could not silence the voices forever. He had always known this. It was just a matter of time. So he did what anyone would have done with new neighbors. He walked over to the fence, stuck out his hand, and befriended them. Problem was, they weren't very good neighbors.

When Gibby interviewed him after his first week, he asked, "Do you consider yourself to be crazy?"

"Sure," Mutt responded without much thought. "It's the only thing that keeps me from going insane." Maybe it was that comment that caught Gibby's eye and caused him to take a particular interest in the case of Matthew Mason.

From middle school onward, he had been diagnosed as everything from schizophrenic to bipolar to schizoeffective to psychotic, manic-depressive, paranoid, long-term, and chronic. In truth, Mutt was all of those things at once and none at the same time. Like the changing tides in the creek outside his window, his illness ebbed and flowed depending on which memory the voices dragged out of his closet. Both he and Tucker dealt with the memories, just differently.

Gibby soon learned that Mutt was no regular schizoeffective-schizophrenic-manic-depressive psychotic with severe post-traumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. He discovered this after one of Mutt's sleepless periods--one lasting eight days.

Mutt was roaming the halls at 4:00 a.m. and had mixed up his nights and days. He had yet to become aggressive, combative, or even suicidal, but Gibby was wary. By the eighth day, he was carry-ing on eight verbal conversations at once, each vying for airtime. On the ninth day, Mutt pointed to his own head, made the "Shhhhh" sign across his lips with his index finger, and then wrote on a piece of paper and handed it to Gibby. The voices, I want them out. All of them. Every last one.

Gibby read the note, studied it for a minute, and wrote back, Mutt, I do too. And we will, but before we send them back to their fiery home, let's figure out which voices are telling the truth and which ones are lying to us. Mutt read the note, liked the idea, looked over both shoulders, and nodded. For seven years he and Gibby had been identifying the liars from the truth tellers. So far, they'd only found one that hadn't lied to him.

About thirty times a day, one of the voices told him his hands were dirty. When Mutt first arrived, Gibby rationed his soap because he couldn't account for its rapid disappearance. Some of the staff thought that maybe Mutt was eating it--they even took away the antibacterial Zest that Mutt specifically requested--but surveillance cameras proved otherwise, so Gibby relented.

Like his hands, his room was spotless. Next to his bed sat one-gallon jugs of bleach, ammonia, Pine Sol, and Windex along with six boxes of rubber gloves and fourteen rolls of paper towels--the sum of which comprised a two-week supply. Again, Gibby was slow to leave the supply in Mutt's room, but after making quite sure that Mutt had no desire to mix a cocktail and, even more, that Mutt actually used it, he loaded him up. Pretty soon his room became the model for families touring the facility or checking on their loved ones. In spite of Gibby's best hopes--which the good doctor shared with him--Mutt's eccentricity had little effect on the guy next door who, for five years, had walked into Mutt's room and routinely defecated in his trash can.

Like most things, Mutt took the cleaning a bit far. If there was metal in his room, and it had been painted, chances were good it was paint-free now. Whether it was a textbook obsession or just something to occupy his hands and mind, Gibby was never quite sure. Through 188 gallons of cleaning solution, he had rubbed the paint, finish, and stain off everything in the room. If his hand or anyone else's hand had touched, could have touched, or might touch in the future, any surface in that room, he cleaned it. On average, he spent more of the day cleaning than not. Whenever he touched something, it had to be cleaned, and not only it, but whatever was next to it, and whatever was next to that. After that the job was anything but finished, because he then had to clean whatever he used to clean it with. And so on. The cycle was so vicious that he even put on a new pair of rubber gloves to help him clean his used pair of gloves before they went in the trash. He went through so many paper towels and rubber gloves that the orderlies finally bought him his own fifty-five-gallon trash can and gave him a case of plastic liners.

The cycle was time consuming, but not as vicious and consuming as the internal loops that kept him captive far more than the walls of his room. The loops were paralyzing, and in comparison, his four walls provided more freedom than the Milky Way. Sometimes, he'd get caught in a question, or a thought or idea, and eight days would pass before he had another thought. Again, Gibby was never certain whether it was truly a physiological condition or something Mutt allowed to keep his mind off the past. But in the grand scheme of things, what was the difference?

During that time, he'd eat little and sleep not at all. Finally, he'd pass out from exhaustion, and when he woke, the thought would be gone and he'd order fried shrimp, cheese grits, French fries, and a jumbo sweet tea from Clark's--which Gibby would personally deliver. This was Mutt's life, and as far as anyone could tell, it would be indefinitely.

The only loops that weren't paralyzing were those tied to a task. For example, taking apart a car engine, carburetor, door lock, computer, bicycle, shotgun, generator, compressor, windmill, anything with a gazillion parts all tied in some logical way to the construction of a perfect system which when assembled did something. Give him a few minutes, a day, a week--and he could take anything apart and have every part laid out on the floor of his room in a maze that only his mind understood. Give him another hour, day, or week, and he'd have it returned to the exact same place performing the exact same function.

Gibby first noticed this talent with the alarm clock. Mutt was late to show for his weekly assessment, so Gibby came to check on him. He found Mutt on the floor surrounded by the alarm clock, which had been disassembled and spread across the floor in hundreds of unrecognizable parts. Figuring the loss was an eight-dollar alarm clock, Gibby backed out of the room and never said a word. Mutt was safe, engaged in a mentally stimulating activity, and relatively happy, so Gibby decided to check on him in a few hours. When afternoon came, Gibby returned to Mutt's room and found Mutt asleep in his bed with the alarm resting just as it should have been on his bedside table, telling good time, and set to go off in thirty minutes--which it did. From then on, Mutt became the Mr. Fix-it of Spiraling Oaks. Doors, computers, lights, engines, cars, anything that didn't work and should.

Tedious detail was not tedious to Mutt. It was all part of the puzzle. One afternoon, Mutt discovered Gibby tying his own flies. He pulled up a chair and Gibby showed him a fly he had bought at a high-end fly-fishing store called The Salty Feather--owned by a couple of good guys who sold good equipment, gave good information, and charged high prices. Gibby had bought a Clauser, a particular fly used for red bass in the grass beds lining the St. Johns. Gibby was sitting at his desk trying to imitate it but having little luck. Mutt looked interested, so Gibby gave him his chair, put on his white coat, and walked down the hall to check on a few patients, never saying a word to Mutt. He returned thirty minutes later and found Mutt tying his fifteenth fly. Gibby's fly-tying book lay open on the desk, and Mutt was copying the pictures. In the months that passed, Mutt made all of Gibby's flies. And Gibby started catching fish.

But beyond engines, clocks, and flies, Mutt's most remarkable talent centered around stringed musical instruments. While he had no interest in playing one, he could tune it to perfection. Violin, harp, guitar, banjo--anything with strings. Especially the piano. It took him a few hours, but given time, he could make each key sing true and crisp as a lark.

-------

Mutt heard the fly before he saw it. His ears zeroed in on the sound, his eyes caught a flash, and his brow wrinkled as he watched it hover around his applesauce. That was not good. Flies carried germs. Maybe today was not the day to not eat his applesauce. He'd just flush the stuff and be done with it . . . But he knew he couldn't do that either. Because in an hour and twenty-two minutes, Vicki, with her shiny panty hose, fitted knee-length skirt, cashmere sweater, and perfume that smelled like Tropicana roses, would walk in and ask him if he had eaten it. At thirty-three years of age, Mutt had never been with Vicki--or any other woman--and his affection for the sound of panty hose rubbing against panty hose was anything but sexual or lustful. But that knee-knocking, woman-soon-to-walk-around-the-corner sound triggered a memory--almost a remembering--that all the others threatened to squeeze out, choked by the forearm-size vines that encrusted it. The swish-swoosh sound of nylon on nylon brought back the notion of being picked up by small but strong hands, of being dusted off and held close and tight to a soft bosom, of being wiped clear of tears, of being whispered to. In the afternoons, he'd lie next to his bedroom door, his ear pushed up against the crack near the floor like a confederate soldier on a railroad track, and listen while she made rounds.

Twenty-five rubber gloves, four rolls of paper towels, and half a gallon of bleach and Windex later, the sound in the hallway at last drew close. A woman's shoes clicking on sterile tile accompanied by the characteristic swish-swoosh, swish-swoosh, swish-swoosh of nylon on nylon.

Vicki walked in. "Mutt?"

Mutt popped his head out of the bathroom where he was scrubbing the windowsill.

She saw the activity and asked, "See another fly?" Mutt nodded. She scanned his lunch tray and settled on his full cup of sauce. "You didn't touch your lunch at all," she said, her voice curiously rising. Mutt nodded again. She held up the bowl and said, "Sweetheart, you feeling okay?" Another nod. Her tone was an even mixture of mother and friend. Like a big sister after having moved back into the house after college. "You want me to get you something else?" she asked, twirling the spoon in her hands and tilting her head, the concern growing.

Great , he thought. Now he'd have to clean the spoon too. No matter. He liked it when she called him "sweetheart."

But sweetheart or not, he still didn't want anything to do with that applesauce. He shook his head and kept scrubbing. "Well, okay." She put the spoon down. "What kind of dessert do you want with your dinner?" Her reaction surprised him. "Something special?" Maybe he didn't have to eat it. Maybe he was wrong. Maybe it wasn't in the applesauce. If not, then where was it? And had he already eaten it?

"Mutt?" she whispered. "What do you want for dessert, sweetie?" His second favorite word. Sweetie. He focused on soft, dark red lips, the tautness around the edges, the way the "ee" rolled out the back of her mouth and off her tongue, and the way the slight shadows hung just below her cheekbones. She raised her eyebrows--as if telling a secret that he must swear to keep--and said, "I could go to Truffles?"

Now she was offering a bone with some meat on it. Truffles was a dessert bar a few miles down the road where a slice of cake cost eight bucks and usually fed four people. Mutt nodded. "Chocolate fudge cake with raspberry sauce."

Vicki smiled and said, "Okay, sweetie." She turned to leave. "See you in the activity room in an hour?" He nodded and let his eyes fall on the chessboard. Vicki was the only one who even came close to competing with him. Although, to be honest, that had little to do with her skill as a chess player. Mutt could usually get her to checkmate in six moves, but he often dragged it out to ten or twelve, sometimes even fifteen. With each impending move, she would tap her teeth with her fingernails, and her feet would become more nervous, unconsciously bouncing beneath the table, causing her knees, calves, and ankles to rub against each other. While his eyes focused on the board, his ears listened beneath the table.

Vicki left and Mutt walked over to the tray where Vicki had placed the spoon. He picked it up, began scrubbing it with a bleach-soaked paper towel, and went through six more towels before it was clean. An hour later, the room sterile, he walked down the hall with his chess set. En route to the activity room, he placed a thirty-six-gallon trash bag in the big, gray community trash can. The can needed cleaning, but Vicki was waiting, so it could wait. He walked into the activity room, saw Vicki, and knew he'd have to clean the chess set after they played--every piece--but it was worth it just to hear her think.

-------

At 5:00 p.m., Mutt finished cleaning his room, his bed, his chess set, his toothbrush, the buttons on his clock radio, and the snaps on his boxers. Out of the corner of his eye, he looked again at the chocolate-raspberry cake covered in deep red raspberry sauce, sitting surrounded by roast beef, green beans, and mashed potatoes. The voices were tuning up and the volume growing louder, so he knew the Thorazine hadn't been in his breakfast. In spite of Vicki's apparent denial, it had to be the applesauce. He knelt down, eyed the mashed potatoes, and wondered if they had been altered. Tampered with. After seven years of total compliance in taking his medication, his own second-guessing surprised him. It was a process and a power he had not known in quite some time. The fact that he was even considering not eating both the applesauce and the chocolate cake would have been mind-boggling except for the fact that he was already mind-boggled.

Finally, he looked out the window and let his gaze fall upon the back porch of Clark's. Due to a southwest wind, he could smell the grease, the fish, the fries; and he could almost taste the cheese grits and see the condensation dripping down a jumbo glass of iced tea. Mutt was hungry, and unlike his neighbor down the hall, his stomach was not in hell. He hadn't eaten in twenty-four hours, and due to the growl, he knew it was right where he left it. But hunger or no hunger, he picked up the tray and smelled each plate, making his taste buds excrete like a puppy with two peters. He held the tray at arm's length, walked to the toilet, methodically scraped the contents of each plate into the bowl, and assertively pushed down on the flush lever.

The voices screamed with approval as the water swirled and disappeared. In an hour Vicki would saunter in, collect the tray, and saunter out. But even in all that sauntering, she would know. Thanks to the cameras, Vicki knew most everything, but he couldn't stop now. This train had no brakes. Mutt again looked at Clark's. The back porch was full, brown tilting Budweiser bottles sparkled like Christmas lights, servers carrying enormous trays holding eight to ten plates wedged themselves between picnic tables, and mounds of food covered every tabletop. In the water next to the dock swam a few hot-rod teenagers who had parked their Jet Skis just close enough for the eating public to admire and yet not touch, and a collage of skiing, pleasure, and fishing boats waited their turn to go up or down the funnel-necked boat ramp. Mutt knew that even after the sirens sounded, after Gibby had grabbed his syringe and the search teams had been dispatched, no one would suspect this, at least not immediately. He might have enough time.

Quickly, he grabbed his fanny pack, walked down the hall to Gibby's office, and lifted the fly-tying vise off his desk. He also grabbed a small Ziplock bag full of hooks, spools of thread, and little pieces of hair and feathers. He quickly tied one red Clauser, laid it in the middle of Gibby's desk, and then stuffed both the vise and the bag in his fanny pack. He opened Gibby's top desk drawer, stole fifty dollars from the cash box, scribbled a note, pinned it to the lamp on his desktop, and walked back to his room. The note read, Gibby, I owe you fifty dollars, plus interest. M.

If he was going on a trip, he would need something to occupy the voices, and they loved two things: chess and tying flies. He stuffed his chess set into his fanny pack next to the vise along with seven bars of Zest, each sealed in its own airtight Ziploc bag. He lifted his bedroom window, took a last look at his room, and swung one leg out. Contractors had originally constructed the windows to set off a silent alarm at the security guard's desk when opened more than four inches. But Mutt had fixed that too about six years ago. He liked to sleep with it open at night. The smells, the sounds, the breeze--it all reminded him of home. He swung his left leg out the window and took a deep breath of air. The September sun was falling, and in an hour, an October moon would rise straight over Clark's back door.

He put his foot down and cracked the base of an azalea bush, but he hadn't liked it since they planted it there last year. It made him itch just to look at it. And it attracted bees. So with a smile on his face, he stomped it a second time and hit the ground running. Halfway across the grassy back lawn, he stopped midstride as if stricken with rigor mortis and thrust his hand in his pocket. Had he forgotten it? He searched one pocket, digging his fingers into the fuzz packed into the bottom, and the worry grew. Both back pockets and the panic came knocking. He thrust his left hand into his left front pocket and broke out in a sweat.

But there in the bottom, surrounded by dryer lint, his fingers found it: warm, smooth, and right where it had been since Miss Ella gave it to him following the first day of second grade. In the dark confines and security of his pocket, he ran his fingers across the front and traced his fingernail through the letters. Then the backside. It was smooth and oily from the years in his pocket. That settled, the fear subsided, and he started running again.

Running was something he used to do a lot, but in the last few years he had had little practice. His first year at Spiraling Oaks, his walk had looked more like that of a soldier stomping the earth--a side effect of too much Thorazine. A few days on that stuff and his mind began to doubt where the earth was. Fortunately, Gibby decreased the dosage and his steps became more certain.

He made it across the back lawn, through the cypress trees bathed in lush green fern, and onto the sun-faded and seagull-painted dock without hearing any commotion behind him. If no one saw him leap off the dock, he might have time for a second helping.

He dove off the end of the dock and into the warm, brackish, and sweet Julington Creek. The water, tinted brown with tannic acid, wrapped around him like a blanket, bringing with it an odd thing: a happy memory. He dove farther in, pulling twelve to fifteen times down, down into the water. When he heard a Jet Ski roar above, he waited a few seconds and surfaced.

Excerpted from Wrapped in Rain © Copyright 2005 by Charles Martin. Reprinted with permission by WestBow Press, an imprint of Thomas Nelson, Inc. All rights reserved.

Wrapped in Rain: A Novel of Coming Home

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Thomas Nelson

- ISBN-10: 0785261826

- ISBN-13: 9780785261827