Excerpt

Excerpt

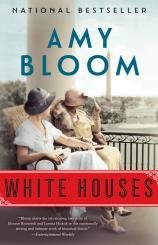

White Houses

PROLOGUE

Friday evening, April 21, 1945

29 Washington Square West

New York, New York

No love like old love.

I’ve done the flowers as best I could. I got stock and snapdragons, pink roses and daffodils from the Italian florist and I’ve put a vaseful in every room. I’ve straightened up the four rooms, which were already neat. The radio still works. The record player works, too, and someone has brought in albums of Cole Porter and Gershwin and there is one scratchy record of La boheme with Lisa Perli from when I visited Eleanor more regularly here. I’ve gone to the corner grocery twice (eggs, milk, bread, horseradish cheese, sardines and I went back again because there was no can-opener) and up the street one more time, for booze. I hope that at five o’clock, we’ll be drinking Sidecars. I bought lemons. I want to have everything we need close by. I am hoping we don’t see so much as the front hall all weekend.

I change my clothes in the living room. I don’t think I should be in the bedroom, at all, unless I get invited. I anticipate sleeping on the couch. I’ve brought my navy blue Sulka pajamas, for old times sake.

On the radio, the newsman raises his voice, and says that the eighteen major cities of Germany are ablaze. That the Potsdam Division of the German Army is systematically murdering the Americans who lie wounded on the battlefield. He says that 2,000 American planes are attacking rail positions near Berlin and other communications centers in southern Germany. He says, ladies and gentlemen, victory is in sight. I hope so. I wish Franklin had lived to see it.

I’ll celebrate the war’s end out on Long Island, with a couple of friends, and we will all toast Franklin Roosevelt, the greatest President I have ever known, and my rival.

I sit down on the living room couch to wait. I used to be able to read Eleanor’s heart, her mood, when I saw her dear face and I worry that I won’t be able to anymore. I expect to see her gray with Roosevelt suffering, the kind that must not only be borne but must be seen to be borne, elegantly, and her great effort to be patient with everyone’s sadness and need and beneath that, just like it was with her brother, a hook of barbed and furious grief that she’d tear out if she could. She told me that nothing on earth was worse than losing her baby, the first Franklin, Junior. I sat with her for the long days of her brother’s Hall’s death, and she cried for him, every night, as if he hadn’t broken everybody’s hearts, as if he hadn’t almost killed one of his own children and ruined the other five. She sat by Hall’s bed, looking like that Henry Adams statue she used to drag me to, the monument of transcendent misery Adams put up when his wife killed herself with cyanide. That’s what I am expecting and I hope that in the mix of her feelings for Franklin, sorrow at his death and grief for her children, and for the country, she will be glad to see me. I want her to feel, that with me, she’s home, like it used to be. She sent me away eight years ago, and I left. Two days ago, she called me to come and I came.

The buzzer rings, which I think means her hands are full and she can’t get to her key.

I open the door and Eleanor is leaning against the wall, paper-white.

Her beautiful blue eyes are red-rimmed, all the way around and she looks as if she has never smiled in her life. Her dusty black coat is enormous on her and her lisle stockings bag. I kiss her because I always kiss her hello, when we are alone and we’re on speaking terms, and she turns her cheek towards me and looks away. I take her purse and her suitcase. I put down the bags and I put my arm around her waist. I try to pull her face to mine but she turns away and rests one hand on my shoulder, to take off her shoes.

She drops her hat, coat and scarf on the big brocade armchair. She unbuttons her grey blouse and lets it fall to the floor. She walks into the bedroom, unzips her skirt and I follow behind, picking up as we go. She sits on the edge of the bed in a ragged white slip she should have thrown out long before the war.

She takes the pins out of her gray hair and pulls off those awful lisle stockings. We fought once about those stockings. I said that even in a war, the First Lady did not actually have to entertain royalty while wearing knit cotton stockings and she said that was exactly what the First Lady had to do. I stretch the stockings over the arm of the club chair.

She lies down on the bed, facing the wall and lifts her right arm up behind her. Without turning to face me, she beckons me over.

“Well, Queen of England,” I say.

She drops her arm. This is not my Eleanor. I used to weep when she was stern and gracious with me, explaining my faults until I curled up like a snail on a bed of salt. She’d sit still and tragically disappointed for an hour or more, until I begged forgiveness. That’s my sweetheart. This waxy indifference is new, and it hurts.

I pile her clothes on the wood chair. I put her black shoes in front of the fireplace. I hang her black coat in the closet, next to my navy blue one and my red scarf falls over them both. I’m sorry I’ve come.

Oh, Hick, she says, if you don’t hold me, I will die.

I climb in behind her and she undresses me with one long white hand, still not turning to look at me.

Twelve years ago we had our golden time and our first vacation. Maine and beyond was our golden hour. Hoover was out. Franklin was in. We all moved in to the White House, friends, family and me.

Eleanor and I had had our first private lunch at the White House, grinning and posing in front of the portraits like teen-age girls. Why don’t you move in, she said. We have so much room.

I asked her what she meant and she said, again, We have so much room. I leaned over to kiss her and she pushed me away a little. I have some housekeeping to do, if you’re coming, she said. Why don’t you go and get your things?

I went back to Brooklyn and put my rent check, almost the full amount, in the mail. I drove my blue suitcase, my Underwood Portable and a box of books down to DC the next day. One of the housekeepers took me through the White House, up the stairs to Eleanor’s suite, blank and polite, as if she’d never seen me before, as if she’d never done my laundry or hemmed my skirt when I’d stayed for the weekend but when she opened the door to my room, she smiled and put my typewriter on the desk. My new room adjoined Eleanor’s.

It was Eleanor’s old sitting room and now it would be my room. I had a big desk, a bookshelf and an old Windsor chair. I had two table lamps and a floor lamp. I had a bed, a dark velvet couch that had seen better days, which I pushed towards the corner and an oak armoire big enough to hide in. The only thing between us was a wall covered with photographs and an old wooden door.

I spent about an hour, sitting upright on my twin bed, my hat and coat still on, staring at that door, willing it to let me in, to look down on the Rose Garden, to let me open the window to the big magnolia tree.

Eleanor finally came in and sat down next to me.

“I shower people with love, because I like to,” she said. “I like showering people with love. You’ve seen me, with my friends.”

I had. It already drove me crazy.

She said, “I want you to know, besides my friends, I have had crushes. I’ll find someone, often someone wonderful, but really, they don’t have to be, and I adore them, no matter what. Doctor Freud would say it’s my mother all over again. Or my father. “

She took off my hat, laughing. I did not do or say a single charming, clever thing. I rubbed my knuckles.

“I am determined to tell you what I want to tell you,” she said. “About the crushes. Because people may tell you, that I’m prone. That this is a crush. They look into my eyes, and they see a whole world of love I have for them. And they love that, and they love me, for the way I love them. They look into my eyes and see themselves at the very center of the world. And they love that.”

She walked over to the wooden door and twisted the knob a few times.

“This thing always sticks.”

“Come back” I said.

She sat back down on the bed, and held my hand, looking straight ahead.

“You see me. You see all of me and I don’t think you love everything you see. I hope you do, but I doubt you do. But, you see me. The whole person. Not just yourself, reflected in my eyes. Not just the person who loves you. Me.”

My ears burnt, the way they did after three Scotches.

Now, she turned and faced me.

“Lorena Alice Hickock , you are the surprise of my life. I love you. I love your nerve. I love your laugh. I love your way with a sentence. I love your beautiful eyes and your beautiful skin and I will love you til the day I die.”

I pushed out the words before she could change her mind.

“Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, you amazing, perfect, imperfect woman, you have knocked me sideways. I love you. I love your kindness and your brilliance and your soft heart. I love how you dance and I love your beautiful hands and I will love you til the day I die.”

I took off my sapphire ring and slipped it onto her pinky. She unpinned the gold watch from her lapel and pinned it on my shirt. She put her arms around my waist. We kissed as if we were in the midst of a cheering crowd, with rice and rose petals raining down on us.

All the way to the Associated Press office, I kept my hand on the gold watch. I knew I had to resign. I’d already quashed a dozen prize-winning Roosevelt stories to protect her, or him, or their kids. I needed to change my beat or give her up.

I did resign. Also, I was fired. I offered to cover some other beat, Wall Street or city crime. My editor pushed back in his chair, folded his hands over his great belly and looked at me like I was the worst kind of cockroach. You’re part of the story, kid, he said. He said, I got the greatest inside track to the White House, ever and I’m not giving that up. In that case, I said, I have to resign altogether. He shrugged like he’d never expected anything more and we shook hands.

Some old pals watched me empty my desk and no one offered to buy me a drink. The woman who did weddings waved, cheerfully. The sportswriter shook his head. The obit guy lifted his hat. (What do you call the Jewish gentleman who leaves the room? Bernard Baruch said to me. A kike.) I had twenty-five dollars in my bank account and no job prospects.

All the way back to the White House, I reminded myself that I was good, that I was honorable, that there was depth and beauty to my sacrifice and that integrity mattered. I wanted it to matter to Eleanor, who’d never had to get or quit a job. She was delighted with me. She believed that all life worth living involved sacrifice and the more the better. This way, she said, we’ll have more time together. This way, we will have our life. She meant that I wouldn’t have to worry about betraying her and she wouldn’t have to worry about my betraying her and I wouldn’t spend so much time with rumpled men who swore and drank Scotch before noon. She hugged me and said, I think this is for the best, Dearest. Franklin rolled by, on cue and said, We got a job for you, Hicky.

I never found out which one of them thought of it first, but they both told me to go talk to Harry Hopkins who was looking for an investigative reporter to help him run Federal Emergency Relief (You report back to Harry, about how bad it is out there, Franklin said. And just be a reporter, not a social worker.). They both told me the pay would be better than what I got at Associated Press. Hopkins hired me in ten minutes, holding my resume behind his back and looking out a window as if he was reading from a script. Thank you, Miss Hickock, I’ll rely on your reports, he said, still looking away.

I ran back to tell Eleanor that I got the job and she smiled.

At five o’clock, another maid came and told me to go downstairs for drinks. Franklin and Eleanor toasted me. Franklin said, Much better to have you inside the tent, Hick, and pissing out.

We planned a vacation (I want to see everything with you, Eleanor said.). We talked Franklin out of sending the Secret Service with us and we loaded up the car and waved to him from the driveway. He waved from the front porch. Behave yourselves, he shouted. We waved back.

We thought we knew everything about each other that mattered and none of what would come to matter was even a mote in our golden light. We had love and this beautiful country, reckless and wide. We had Eleanor’s very sporty light blue Buick roadster and enough money for everything we wanted, or even were just in the mood for. Eleanor wrapped her hair in a scarf and dangled one arm over the side of the car, like a movie star. We glided from place to place, in love, in rapture, enjoying each day, all day and moving on, just so as to enjoy more.

We camped and talked. I sang to Eleanor, every hymn I’d ever learned and dirty songs to make her put her hands over her ears. (A lot of things rhyme with Hick.) We loaded the backseat with bags of pretzels, brand new sunglasses, a stack of maps, a bag of Eleanor’s knitting, which made me laugh, a deck of cards, just in case, and books of poetry (Wild nights, I recited, while she drove. Wild nights, were I but moored in thee. Moored, I yelled again, until she blushed. I admire Emily Dickinson, Eleanor said.)

I’d packed my navy pajamas and she’d packed her pink nightgown and one night, in a nearly empty hotel in Vermont, she put on the pajamas and I put on the nightgown and we almost broke the bed. She wrote to Franklin regularly. Just so that he won’t worry, she said. Send my regards, I said. Sometimes people recognized her, and we’d stop and I’d back away, to the car, or into a shop, so she could sip the lemonade or the cider, and admire the children or the quilts, and pose for a picture if someone had a camera, which they rarely did, because we were so far from the modern world, up there. She’d started out as not much of a public speaker and she’d made herself a good one. She couldn’t tell a joke to save her life. But Eleanor could listen. Every person she spoke to was her hero. Angry logger, blind widow with a Rose of Sharon quilt, hopeful musician, grateful nurse at the end of the graveyard shift, mother of six with her hand crushed in the factory. She came close. She bent her head towards yours and she slowed and she listened. She settled and got still. She didn’t look, for a second, as if she was thinking about anything except you and your story. If you hesitated because you were worn out or embarrassed, she leaned forward as if she couldn’t bear that you would now, in the middle of this moment between you, turn away from her.

We love the attentiveness of powerful people, because it’s such a pleasant, gratifying surprise but Eleanor was not a grand light shining briefly on the lucky little people. She reached for the soul of everyone who spoke to her, every day. She bowed her head towards yours, as if there was nothing but the time and necessary space for two people to briefly love each other.

Mostly we met farmers and elderly Republicans, people who didn’t look at newspapers, if they could help it, except for local news and sports and feed prices. Mostly, we were, as we liked to pretend, Jane and Janet Doe, walking arm-in-arm, talking mouth to ear. Middle-aged women who liked each other: sisters, cousins, best friends. We kept ourselves to ourselves, except for Eleanor’s strong wish to be pleasant to everyone, and, mostly people thought of us whatever people think of middle-aged ladies and that’s all.

We took a break from people and the quilts and Eleanor drove us to Quebec, to Chateau Frontenac, telling me, as we got to the outskirts, Close your eyes. I think when I am an old lady, when people have to shout to get my attention, you could murmur Chateau Frontenac and I will smile like a cat paw-deep in cream. Eleanor did for us what she never liked doing for herself and she did it on a grand scale, with gilt edges. We sat, I should say, we cavorted, in the French-Canadian lap of luxury. We got massages together with two strong ladies coming into our suite with two massage tables, picnic baskets of warm towels and rose and orange oils. I pretended that I’d somehow wandered in from the hide-a-bed in the living room. They set up the tables and indicated we should strip and wrap ourselves in sheets. We did and we tottered over to the tables, to be rubbed and patted by these two frowning women who couldn’t understand our language. Our faces only two feet apart, our bodies glistening with rose-scented oil.

I said, ‘This is too much.”

“I know,” Eleanor said. “We have manicures after lunch. “

I said to Eleanor, This is our trip to Erewhon and she agreed. Our particular Nowhere, she said, will be found at the northern tip of Maine. Get your sweater. We drove to a cabin overlooking the ocean at dusk and unpacked before dark. We shared a brandy and the last of the pretzels and stood in our nightclothes on the little porch, the big quilt around us. The mottled, bright white moon pulled the tide like a silver rug, onto the dark, pebbled beach. It should have been a starry sky, but it was deep indigo, like the sea below, with nothing in it but the one North Star.

“I’m making a wish,” I said.

We ate potato pancakes for breakfast. (Every café and diner featured potatoes. We had buttery and cheesy grated potatoes mounded into potato skins, which were delicious and chocolate cake, enhanced with mashed potatoes, which was not.) We took walks and designed our dream cottage. Sometimes it was another version of her beloved Val-Kill, a Hyde Park cottage that was a rabbit warren of rooms with plenty of space, a library and a communal dining room. Sometimes, it was a cottage on Long Island, where I now live, rose-covered and overlooking the Sound. One night, I made shadow puppets of everything we would see from our dream porch. I did a fox, a heron, a squirrel and two people kissing, which is all the shadow puppetry I knew. We had tuna fish sandwiches on the rough, windy beach and furnished our dream apartment in Greenwich Village. We imagined trips to places neither of us had been. How about Gaspe Bay, I said. We’ve never been here before. Baie de Gaspé, she said. All right, I said. Let’s add Upper Gaspe, Land’s End, Chaleur Bay. Don’t forget Armonk and Massapequa. The Long Island nightspots.

I imagined Eleanor telling her children about us. If they’d been actual children, I would have liked my chances better. I’d have told them myself, if they were actual children. Children liked me. I was quick with the cookies, and slow to scold. I could bait a hook, build a house of cards and make strawberry shortcake. I winked behind their mothers’ backs when they had their hands on the last biscuit and I liked the feel of a small child on my shoulder. I was a natural but the Roosevelt boys were spoiled and empty and endlessly wanting and Anna was pretty and shrewd. She could’ve been a cooch dancer at L’etoile du Nord, if she’d had a stronger work ethic. I felt for them all what the hard-working poor feel for the rich (not, by and large, admiration and affection) and they felt for me what children feel about that person who seems to have your mother’s heart. I might be able to get Anna on my side but the thought of telling Eleanor’s sons anything shut me up.

Eleanor pointed out that we did not have to make an announcement.

“It’s not as if we’re calling them into the Oval Office. There’s no need for fuss,” she said.

She sat the way she did when she lectured her children, spine straight, hands clasped. I threw a pillow at her and she ducked.

“It’s the end of his term—“

“He’ll have two terms,” I said.

She frowned.

“Pretend I never spoke. ” I said. “Carry on.”

“We say, ‘My dears, now that Father is no longer President, he and I have the opportunity to continue in public service, and continue our marriage. But we will also go our separate ways.’”

“Which is nothing new,” I said.

“That’s correct. I say that Franklin and I will always be a team, of course.”

“Of course,” I said. “Boola-boola.”

“That’s Yale,” she said, shaking her head.

And I say, “Then Junior collapses likes he’s been shot, Jimmy gets drunk, John asks for an increase in his allowance and Elliot starts screaming about ‘who will look after poor Pater?’”

“Jimmy is not that big a drinker. I say to them ‘Your father and I love each other and our marriage will continue. I say ‘You may visit him at Campobello and you may visit us…’”

She wiped her eyes.

“This is a silly game,” she said. “When the time comes, you and I will move into Val-Kill, that’s all.”

“That’s plenty,” I’d said.

White Houses

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Random House Trade Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0812985699

- ISBN-13: 9780812985696