Excerpt

Excerpt

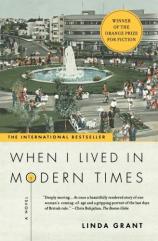

When I Lived in Modern Times

Chapter 1 When I look back I see myself at twenty. I was at an age when anything seemed possible, at the beginning of times when anything waspossible. I was standing on the deck dreaming; across the Mediterranean we sailed, from one end to the other, past Crete and Cyprus to where the East begins. Mare no-strum. Our sea. But I was not in search of antiquity. I was looking for a place without artifice or sentiment, where life was stripped back to its basics, where things were fundamental and serious and above all modern.

This is my story. Scratch a Jew and you’vet got a story. If you don’t like elaborate picaresques full of unlikely events and tortuous explanations, steer clear of the Jews. If you want things to be straightforward, find someone else to listen to. You might even get to say something yourself. How do we begin a sentence?

"Listen . . ."

A sailor pointed out to me a little ship on the horizon, one whose role as a ship was supposed to be finished, which had reached the end of its life but had fallen into the hands of those who wanted it to sail one last time. "Do you know what that is?" he asked me.

I knew but I didn’t tell him.

"It isn’t going to land," he said. "The authorities will catch them."

"Are you in sympathy with those people?"

"Yes, I’m sympathetic. Who wouldn’t be? But they can’t go where they want to go. It’s just not on. They’ll have to find somewhere else."

"Where?"

"No idea. That’s not our problem, is it?"

"So you don’t think the Zionist state is inevitable?"

"Oh, they’ll manage somewhere or other. They always have done in the past."

This time it’s different, I thought, but I kept my mouth shut. Like the people on the horizon, I was determined that I was going home, though in my case it was not out of necessity but conviction.

Then I saw it, the coast of Palestine. The harbor of Haifa assumed its shape, the cypress and olive and pine-clad slopes of Mount Carmel ascended from the port. I didn’t know then that they were cypresses and olives and pines. I didn’t recognize a single thing. I had no idea at all what I was looking at. I had come from a city where a few unnamed trees grew out of asphalt pavements, ignored, unseen. I could identify dandelions and daisies and florists’ roses but that was all, that was the extent of my excursions into the kingdom of the natural world. And what kind of English girl doesn’t look at a tree and know what type it is, by its bark or its leaves? How could I be English, despite what was written on my papers?

On deck, beside me, some passengers were crossing themselves and murmuring, "The Holy Land," and I copied them but we were each of us seeing something entirely different.

I know that people regarded me in those days as many things: a bare-faced liar; an enigma; or a kind of Displaced Person like the ones in the camps. But what I felt like was a chrysalis, neither bug nor butterfly, something in between, closed, secretive, and inside some great transformation under way as the world itself—in that strangest of eras just after the war was over—was metamorphosing into something else, which was neither the war nor a return to what had gone before.

It was April 1946. The Mediterranean was packed with traffic. Victory hung like a veil in the air, disguising where we might be headed next. Fifty years later it’s so easy, with hindsight, to understand what was happening but you were part of it then. History was no theme park. It was what you lived. You were affected, whether you liked it or not.

We didn’t know that a bitter winter was coming, the coldest in living memory in the closing months of 1946 and the new year of 1947. America would be frozen. Northern Europe would freeze. You could watch on the Pathé newsreel women scavenging for coal in the streets of the East End of London. I had already seen in the pages of Life magazine what was left of Berlin—a combination of grandeur and devastation, fragments of what looked like an old, dead civilization, the wreckage that was left in the degradation of defeat. I had seen people selling crumbs of what had once been part of a civilized life. A starving woman held out a single red, high-heeled shoe. A man tried to exchange a small bell for a piece of bread. A boy offered a soldier of the Red Army his sister’s doll.

All across the northern hemisphere would be the same bitter winter. The cold that killed them in Germany would kill us everywhere. But winter was months away and I was on deck in balmy spring weather, holding the green-painted rail of the ship, watching the coast of Palestine assemble itself out of the fragrant morning air and assume a definite shape and dimension.

In the Book of Lamentations I had once read these words: Our inheritance is turned to strangers, our houses to aliens. Our skin was black like an oven because of the terrible famine. The ways of Zion do mourn, because none come to the solemn feast: all her gates are desolate: her priests sigh, her virgins are afflicted, and she is in bitterness.

But all that was about to change. We were going to force an alteration in our own future. We were going to drive the strangers out, bury the blackened dead, destroy the immigration posts and forget our bitterness. There would be no more books of lamenting. Nothing like that was going to happen to us again. We had guns now, and underground armies, guerrilla fighters, hand grenades, nail bombs, a comprehensive knowledge of dynamite and TNT. We had spies in the enemies’ ranks and we knew what to do with collaborators.

I was a daughter of the new Zion and I felt the ship shudder as the gangplank crashed on to the dock. I put on my hat and white cotton gloves and, preparing my face, waited to go ashore at the beginning of the decline and fall of the British Empire.

Excerpted from When I Lived in Modern Times © Copyright 2012 by Linda Grant. Reprinted with permission by E.P. Dutton. All rights reserved.

When I Lived in Modern Times

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 272 pages

- Publisher: Plume

- ISBN-10: 0452282926

- ISBN-13: 9780452282926