Excerpt

Excerpt

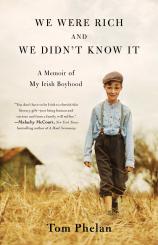

We Were Rich and We Didn't Know It: A Memoir of My Irish Boyhood

IN THE FARMHOUSE KITCHEN

In our farmhouse on Laragh Lane in Mountmellick, the kitchen was also the dining room, the children’s playroom, the sitting room, the workroom, the place where turkeys and chickens were plucked, and where new litters of pigs were kept warm in cardboard boxes while Dad broke off their front teeth with pliers to prevent them from biting their mother’s teats.

The only source of heat in the house was the kitchen fireplace. The bedrooms and parlor were cold and damp, and we slept with our school clothes folded between the sheets to have them warm for the following morning. Hot water bottles were used for most of the year. All dry overcoats in the house served as extra blankets.

On Saturday nights in our kitchen, preparations were made for attendance at mass the next morning: Dad shaved, Mam polished shoes, Dad washed the children, Mam dried us and fine-combed our hair for fleas, and Dad trimmed our nails.

Early in the evening the big black cast-iron pot—also used for boiling gruel, potatoes for the pigs, Christmas puddings, and Monday-morning laundry water—was hung from the crane above the fire. Because the hard limestone water from the well made it difficult to work up a lather, the pot was filled with soft water from the concrete tank at the wicket door.

“But I saw worms wriggling in the tank.” “Sure, what’s a few boiled worms?”

While the water heated, Mam placed a basin, towel, shaving brush, yellow soap, comb, and folded newspaper on the table in preparation for Dad’s weekly performance with his razor. Then she sat at the fire, with her back to the place of Dad’s high-wire act, and shined the shoes. As if the smell of Kiwi polish activated an alarm in his brain, Dad stood up and walked into the boys’ room. He returned with the wood-framed, tilting, shaving mirror.

The money box on top of the dresser was never touched by the children; neither was the Sacred Heart lamp, the key to the kitchen door, the serrated bread knife, Mam’s rod hanging beneath the mantelpiece, the door latch of Uncle Jack’s room, the sugar bowl, the matches on the mantel, or the key for winding the clock. But above all else, Dad’s razor was so much off-limits that I imagined it was a murderous weapon with a mind of its own, ever watchful for flesh as it lay in its lair in the drawer under the mirror. It was a wild animal that only the strong hand of a man could control, but even in the strongest of hands, it could still sink its teeth into the face of the shaver.

When Dad lifted the paraffin lamp off its nail on the wall and placed it beside the mirror, the shadows in the kitchen changed, robbing it of its familiar, comforting qualities. The atmosphere became colder, and the anticipation of Dad’s derring-do caused the hairs on my neck to move.

My four siblings and I gaped at Dad shaving as if mesmerized by a snake’s twitching tongue. Down the side of his face the razor loudly scraped, leaving in its wake a clean, pink swath. I held my face within my palms as Dad’s cheeks and jaws appeared from under the soap.

I had often helped Dad as he slit the throats of turkeys bound for the Christmas market, and so I grasped the seat of my chair when he dragged his razor down his throat, not even slowing as it approached his Adam’s apple, and bumped over it like a bike going over Rourke’s Bridge. Then the razor was climbing back up his throat to clear the stubbles the downward passes had missed. The slopes of his Adam’s apple were ascended and descended with no regard for safety. With thumb and index finger at each side of my throat, I pressed against my skin to save him from slicing into a pulsing artery. More soap was brushed on and the fingers of Dad’s left hand were used to make level the passage of the razor across the hilly surfaces of his chin. When he lifted his nose to get at his philtrum, exposing his nostrils in the mirror, my sister put her hands over her eyes and bent her head to the table.

“He looks like a pig,” she said.

When Dad finally finished, he hung the lamp back on its nail, and the familiar comfort and warmth of the kitchen returned.

Back at the basin, Dad lathered his hands. Then, like a starling in a loch of water on Laragh Lane, he scrubbed his face and ears and neck, his face almost in the basin, drops of water in the air around him. Then he scooped water over his head, and washed his hair with the yellow soap. When he’d rinsed out most of it, he poked his ears with his thick farmer’s fingers.

“Nan,” he said, and Mam dipped a saucepan into the pig pot, cooling it with mugs of cold water from the kitchen bucket. She held the pan over Dad’s head, the soapy water falling into the basin like liquid icicles pouring off the eaves of a thatched roof on a long day of heavy rain. Then Dad toweled himself with the same intensity he applied to everything he did: his head became the center of a flurry, a whirlwind towel chased by two hands full of impatient fingers.

Next he ran a close-toothed, flea-catching, ivory comb through his soft hair, inspecting it for victims after each pass. If he found one he squashed it between his thumbnail and the ivory, the tinny click bringing a protesting grunt from my sister. Then before resuming the hunt he wiped the comb on the arse of his trousers.

When he had stowed away the mirror and cleared the table, Dad put on his cap and went out to the dairy to fetch the two-handled galvanized bath. The bath was also used for the Monday morning laundry and as a carrier for apples and potatoes. Once a year it was positioned beneath a lifeless, hanging pig to catch its intestines when Mister Lowndes slit its belly from nave to chaps with one drag of his knife.

To our boggish tongues the bath was a “baa.” It was three feet long with fifteen-inch sides, a handle at each end. Giving loud instructions for everyone to stand back, Dad lifted the pig pot off its hook over the fire, carried it to the baa in the middle of the floor and, using his cap to grasp one of the three legs, tilted in most of the water. Steam billowed to the clothesline near the ceiling.

Soon Dad was on the floor beside the baa, roughly scrubbing a child’s body.

“Ow!”

“Well, if you didn’t get your insteps so dirty . . .”

When my turn came and the stinging soap was rubbed into my hair, I clamped my eyes shut until the saucepan delivered its cascade of flushing water. Then I stepped out of the baa into the towel on Mam’s lap at the fireplace. When she had dried me, brushed my hair straight, and used the ivory flea-catcher, I was unseated to make room for the next child. Those few moments in her lap within the radius of the fire’s heat were like soaking in a bath of warm, silver grace.

In pajamas and shoes we lined up to have our nails cut. Using scissors large enough to trim a box hedge, Dad examined each finger for signs of nail biting. When an accusation was made and a lie of denial told, the accused received a slap on the back of the hand; the evidence of biting was pointed to, the accusation was repeated, and the truth was told.

“You’ll have to tell that lie in confession.”

Our Saturday night ablutions completed, Mam and Dad lifted the bathful of used water onto two chairs facing each other “to get it out of the way,” and then we were sent to bed, hot water bottles under our oxters.

Years later I realized Mam had bathed in the baa water after we children had gone to sleep.

We Were Rich and We Didn't Know It: A Memoir of My Irish Boyhood

- Genres: Memoir, Nonfiction

- paperback: 224 pages

- Publisher: Gallery Books

- ISBN-10: 150119710X

- ISBN-13: 9781501197109