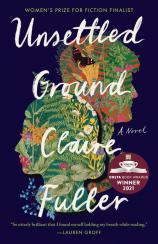

Unsettled Ground

Review

Unsettled Ground

Morning. An April snowfall. A ramshackle cottage in the English countryside. In the opening scene of UNSETTLED GROUND, 70-year-old Dot narrates her own lonely death, and then the perspective shifts to that of her twin children, Jeanie and Julius, who have dwelled with her in this house all their lives. They are now 51 years old, with a very marginal connection to schools, shops, regular jobs, bank accounts and medical care --- all the markers of modern, conventional society. They are literally babes in the wood. Claire Fuller will show us their struggle to grow up.

This is not the first time Fuller has created characters who abandon civilization, so called, for the wilderness. OUR ENDLESS NUMBERED DAYS, the British writer’s remarkable debut novel about a girl and her obsessive survivalist father, won the UK’s Desmond Elliott Prize. The mother in UNSETTLED GROUND, Fuller’s fourth novel, is more benign, if not entirely blameless. Although Dot dies in the first few pages, her spirit, her courage, her ingenuity --- and, it turns out, her many secrets and deceits --- dominate the book.

UNSETTLED GROUND has already been published in the UK and is on the shortlist for the 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction, an elite six-book group that also includes Patricia Lockwood’s NO ONE IS TALKING ABOUT THIS, TRANSCENDENT KINGDOM by Yaa Gyasi, and Brit Bennett’s THE VANISHING HALF. Fuller’s novel deserves the honor and, I suspect, will reap more now that it is out in the United States.

"[W]hat is so marvelous about UNSETTLED GROUND is the way Fuller taps into and dramatizes the universal experience of adult children following a parent’s death."

If you have a yen for fantasies of rural coziness, UNSETTLED GROUND is not your ideal read. The Seeder family (the name is apt) subsists on the proceeds from the sale of eggs, vegetables and fruit, plus odd jobs Julius finds in the immediate area (he gets carsick in any moving vehicle and can’t go far). Fuller doesn’t romanticize the back-breaking labor required to keep things going: the garden, the chickens, the fire that must never be allowed to go out. Yet her exquisitely detailed descriptions of the work Jeanie and Dot once did side by side and that she must now do alone --- making a rabbit pie, potting tomato seedlings, clearing nettles from the garden with a scythe --- have their own kind of beauty and pathos. And the mournful folk ballads the family is fond of playing and singing form a counterpoint to the unforgiving demands of their life.

The twins’ existence is fragile: One illness or injury, one loss, one snowstorm, one threat, one debt, and they teeter on the edge of the abyss. Shortly after their mother’s death, Julius and Jeanie receive an eviction notice from their affluent farmer neighbor, who owns the land. How and where they will live if that happens becomes the pivot for Fuller’s suspenseful and heartbreaking plot.

The story unfolds alternately from Julius and Jeanie’s standpoints, and the reader’s view of their characters, and that of their mother, evolves interestingly as the novel progresses. At first, Julius seems more worldly, more mature. He gets away from the cottage for work, goes to the local pub, has a cell phone, and acquires a girlfriend of sorts. Jeanie, on the other hand, is functionally illiterate and far more isolated. Told at age 13 by her mother that she has a heart condition, she has remained tucked away at home ever since.

Gradually, though, as Jeanie is forced to take on some of the “outside” tasks that her mother performed, like going to the village shop, she emerges as the stronger person. Julius is a bit feckless; he likes his pint and his roll-up cigarettes, and while he yearns for someone to love, he is clumsy at courtship. Jeanie turns out to be surprisingly brave and steady. She makes a home of sorts in the most desperate of circumstances, stands up to bullies, and even manages to find a paid gardening job: “The idea of doing work other than looking after her own house and garden makes her feel like something inside her, as tiny as an onion seed, is splitting open, ready to send out its shoot.”

Our picture of Dot changes most of all. It soon becomes clear that after she was widowed some 40 years ago, this apparently self-sufficient woman was in dreadful fear of being alone. To keep the children with her, she lied: about her husband’s death, Jeanie’s health, Julius’ responsibility as the man of the family. She bound them all to this intimate but cloistered life.

I loved UNSETTLED GROUND. The one flaw in the novel, in my opinion, comes in the final chapters. Fuller jumps ahead a year and busies herself tying up every possible loose end. Money and security and friendship seem to arrive as if by magic, mainly through the good offices of Bridget, a generous if annoying friend of their mother; Jeanie’s bohemian employer, Saffron; and the neighbor, Rawson, who had a secret history with Dot.

I wasn’t sorry to see some prosperity come Jeanie and Julius’ way after all they’ve been through. Part of Fuller’s brilliance is how much she gets the reader to care for them both, despite their prideful stubbornness and dangerous innocence. But in this case, I think the ending slightly undermines the subtlety of the rest of the book. I wanted the conclusion to be less neat, more fluid.

That aside, what is so marvelous about UNSETTLED GROUND is the way Fuller taps into and dramatizes the universal experience of adult children following a parent’s death. Like all of us, Jeanie and Julius grow up with an edited version of reality; it is only after Dot is gone that they can let go of the story they’ve told themselves --- or that’s been told to them --- about their lives.

It’s heartening that Jeanie at least finally gets a chance to part ways with the past and find her own truth.

Reviewed by Katherine B. Weissman on May 22, 2021

Unsettled Ground

- Publication Date: April 26, 2022

- Genres: Fiction

- Paperback: 330 pages

- Publisher: Tin House Books

- ISBN-10: 1953534171

- ISBN-13: 9781953534170