Excerpt

Excerpt

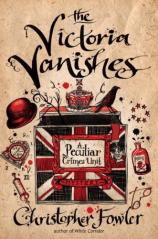

The Victoria Vanishes

Chapter One

Asleep in the Stars

She had four and a half minutes left to live.

She sat alone at the cramped bar of the Seven Stars and stared forlornly into her third empty glass of the evening, feeling invisible.

The four-hundred-year-old public house was tucked behind the Royal Courts of Justice. It had been simply furnished with a few small tables, wooden booths and framed posters of old British courtroom movies. Mrs Curtis had been coming here for years, ever since she had first become a legal secretary, but every time she came through the door, she imagined her father's disapproval of her drinking alone in a London pub. It wasn't something a vicar's daughter should do.

Hemmed in by barristers and clerks, she could not help wondering if this was all that would be left for her now. She wanted to remain in employment, but companies had grown clever about making women of a certain age redundant. After her last pay-off, she had spent time working for a philosophical society instead of heading back into another large firm. Now she was waiting for --- what exactly? Someone to surprise her, someone to appreciate her, someone ---

She stared back into the melting ice cubes.

Her name was Naomi, but her colleagues called her Mrs Curtis. What was the point of having an exotic name if nobody used it? She was sturdy-beamed and rather plain, with thick arms and straight bangs of greying hair, so perhaps she looked more like a Curtis to others. If she had married, perhaps she would have gained a more appealing surname. She regretted having nothing to show for the past except the passing marks of time.

She checked the message on her cell phone again. It was brief and unsigned, but casual acquaintances sometimes called and suggested a drink, then failed to turn up; the legal profession was like that. Looking around the bar, she saw no-one she recognised. Friends usually knew where to find her.

'Give me another Gordon's, darling. Better make it a double.'

Adorable boy, she thought. The barman was impossibly slim, probably not much older than twenty-one, and didn't regard her with pity, just gave her the same friendly smile he bestowed on everyone else. Probably Polish; the ones who worked in bars now were quick to show pleasure, and had a rather old-fashioned politeness about them that she admired.

She touched her hair and watched him at work. She would never eat alone in a restaurant, but taking a drink by herself in a pub was different. Nobody knew her past here, or cared. For once, there were no tourists in, just the Friday night after-office crowd jammed into the tiny narrow rooms and spread out across the pavement on an unnaturally warm winter night. It had to be a lot colder than this to stop the city boys from drinking outside.

When she noticed him, it seemed he had been standing at her side for a while, trying to get served. 'Here,' she said, pushing back her stool, 'get in while you can.'

'Thanks.' He had a nice profile, but quickly turned his head from her, probably because of shyness. He was a lot younger than she, slightly built, with long brown hair that fell across his face. There was something distantly recognisable about him. 'Can I get you one while I'm here?' he asked. Rather a common voice, she thought. South London. But definitely familiar. Someone I've talked to after a few gins?

'Go on, then, I'll have another Gordon's, plenty of ice.'

He slid the drink over to her, looking around. 'I wonder if it's always this crowded.'

'Pretty much. Don't even think about finding your way to the toilets, they're up those stairs.' She pointed to the steep wooden passageway where a pair of tall prosecutors were making a meal out of having to squeeze past each other.

He muttered something, but it was lost in a burst of raucous laughter behind them. 'I'm sorry, what did you say?' she asked.

'I said it feels like home in here.' He turned to her. She tried not to stare.

'My home was never like this.'

'You know what I mean. Cosy. Warm. Sort of friendly.'

Is he just being friendly, she thought, or is it something else? He was standing rather too close to her, and even though it was nice to feel the heat of his arm against her shoulder, it was not what she wanted. In a pub like this everyone's space was invaded; trespass was part of the attraction. But she did not want --- was not looking for --- anything else, other than another drink, and then another.

He showed no inclination to move away. Perhaps he was lonely, a stranger in town. He liked the pubs around here, he told her, Penderel's Oak, the Old Mitre, the Punch Tavern, the Crown & Sugarloaf.

'Seen the displays in the window outside this place?' he asked.

She turned and glanced at the swinging pub sign above the door, seven gold-painted stars arranged in a circle. The wind was rising. In the windows below, legal paraphernalia had been arranged in dusty tableaux.

'Wigs and gowns, dock briefs. All that stuff for defending criminals, nonces and grasses.' He spoke quickly, almost angrily. She couldn't help wondering if he'd had trouble with the police. 'I used to meet my girlfriend in pubs like this. After she left me I got depressed, thought of topping myself. That's why I keep this.' He dug in his pocket and showed her a slender alloy capsule, a shiny bullet with his name etched onto the side. 'It's live ammunition. If things get too much I'd use it on myself, no problem. Only I haven't got a gun.' He'd finished his beer. 'Get you another?'

She wanted more gin but demurred, protested, pushing her stool back by an inch. He seemed dangerous, unpredictable, in the wrong pub. He took her right arm by the elbow and guided it back onto the bar with a smile, but gripped so firmly that she had no choice. She looked around; most of the standing men and women had their backs to her, and were lost in their own conversation. Even the barman was facing away. A tiny, crowded pub, the safest place she could imagine, and yet she suddenly felt trapped.

'I really don't want another drink. In fact I think I have to ---' Was she raising her voice to him? If so, no-one had noticed.

'This is a good place. Nice and busy. I think you should stay. I want you to stay.'

'Then you have to let go ---' But his grip tightened. She reached out with her left hand to attract the attention of the barman but he was moving further away.

'You have to let go ---'

It was ridiculous, she was surrounded by people but the noise of laughter and conversation was drowning her out. The crush of customers made her even more invisible. He was hurting her now. She tried to squirm out of his embrace.

Something stung her face hard. She brought her free hand to her cheek, but there was nothing. It felt like an angry wasp, trapped and maddened in the crowded room. Wasn't it too early in the year for such insects?

And then he released her arm, and she was dropping, away through the beery friendship of the bar, away from the laughter and yeasty warmth of life, into a place of icy, infinite starlight.

Into death.

Chapter Two

The First Farewell

Early Monday in Leicester Square. On a blue-grey morning like this the buildings looked heavier, more real somehow in rain than in sunlight. Drizzle drifted on a chill breeze from the north-east. The sky that smudged the rooftops felt so low you could reach up and touch it.

John May, Senior Detective at the Peculiar Crimes Unit, looked around as he walked. He saw cloud fragments in lakes on broken pavements. Shop shutters rolling up. Squirrels lurking like ticket touts. Pigeons eating pasta. Office workers picking paths through roadworks as carefully as cats crossing stones.

The doorways that once held homeless kids in sleeping bags now contained plastic sacks of empty champagne bottles, a sign of the city's spiralling wealth. Piccadilly Circus was once the hub of the universe, but today only tourists loitered beside the statue of Eros, trying to figure out how to cross the Haymarket without being run over.

Every city has its main attraction, May thought as he negotiated a route through the dining gutter-parrots in the square. Rome has the Coliseum, Paris the Tour Eiffel, but for Londoners, Leicester Square is now the king. It seems to have wrested the capital's crown away from Piccadilly Circus to become our new focal point.

He skirted a great puddle, avoided a blank-faced boy handing out free newspapers, another offering samples of chocolate cake.

This is the only time of the day that Leicester Square is bearable, he thought. I hate it at night. The sheer number of people standing around, what do they all wait here for? They come simply because it's Leicester Square. There's not even a chance they'll spot Tom Cruise having his photo taken on a girl's cell phone, because everyone knows film premieres only take place on weeknights. There's nothing to see other than a giant picture of --- who is it this week? --- Johnny Depp outside the Odeon cinema, plus a very small park, the cheap ticket kiosk and those parlours selling carpet-tile pizzas that you could dry-stone a wall with. At least Trafalgar Square has Nelson.

The scene before him was almost devoid of people, and could not reveal the diegesis of so many overlapping lives. The city was shaped by assembly, proximity and the need for companionship. Lone wolves can live in the hills, but London is for the terminally sociable.

May caught sight of himself in a shop window. On any other day, he would have been pleased to note how neatly he fitted his elegant suit. He had remained fit and attractive despite his advancing years. His hair had greyed, but his jaw and waist were impressively firm, his colouring healthy, his energy level consistently high. All the more reason to be angry, he thought, but today he had good reason to be ill-tempered. He had just come to the realisation that he might very well be dying.

He tried not to think about the sinister manila envelope in his briefcase, about the X rays, the Leicester Square Clinic's referral letter, and what this meant to his future. For once he just wanted to enjoy London and think of nothing in particular, but the city wasn't letting him.

I remember when the square was different. Bigger and leafier, with cars slowly circling it and thousands of starlings fluttering darkly in the trees, that busker in a fez doing a sand-dance for coins outside the Empire. Look at the state of the place now. Kids need a purpose for coming here other than getting their iPods nicked. What will the next tawdry attraction be, I wonder, celebrity mud-wrestling or the National Museum of Porn? At least I won't be here to witness the indignities thrust upon it. I'll be long gone. I used to drink mild and bitter in The Hand & Racquet with Arthur, then take a Guinness in the Green Man & French Horn over in St Martin's Lane. I wonder if we'll ever do that again? I always thought he would go first, but what if it's me? What on earth will Arthur do then?

Bryant & May. Their names went together like Hector and Lysander, like Burke & Hare, unimaginable in separation. May still felt young although he was far from it. He still looked good and felt fit, but his partner in crime detection, Arthur Bryant, was growing old before his eyes. Arthur had all his critical faculties, far more than most, but the physical demands of the job were wearing him down. May wondered whether to hide his news from his partner for fear of upsetting him.

Despite his dark thoughts, May was still at his happiest here, walking to work through the city on a rainy February morning. Being near the idealistic young was enough to provide him with the energy to survive. He tried to imagine how visitors felt, seeing these sights for the first time. Every year more nationalities, more languages, and the ones who stayed on became Londoners. It was an appealingly egalitarian notion. More than anything, he would miss all of this. Culinary terms were appropriate for the metropolis; it was a steaming stew, a broth, a great melting pot, momentarily levelling the richest and poorest as they rubbed shoulders on the streets.

Striding between the National Portrait Gallery and St Martin in-the-Fields, he briefly stopped to reread the wording beneath the white stone statue of Dame Edith Cavell, the British nurse who faced a German firing squad for helping hundreds of soldiers escape from Belgium to the Netherlands. The inscription said: 'Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.' If there's a more respectful creed by which to live, May thought, I can't imagine what it is.

He put the blame squarely on London and the strange effect it had on people. If he hadn't come here as a young man and met Bryant, he would never have been infected with his partner's passion for the place. He wouldn't have stayed here all these years, unravelling the crimes deemed too abstract and bizarre to occupy the time of regular police forces. And even now, knowing that it might all come to an end, he could not entertain the thought of leaving.

Curiosity finally got the better of him, and he stopped in the middle of the pavement to take out the envelope and tear it open. He could feel the letter inside, but did he have the nerve to read it?

A good innings, some would say. Let the young have a go now. Time to turn the world over to them. To hell with it. With a catch in his heart, he pulled out the single sheet of paper and unfolded it, scanning the two brief paragraphs.

A tumor attached to the wall of his heart, a recommendation for immediate surgery, a serious risk owing to past cardio-vascular problems that had created a weakness possibly leading to embolisms.

He took a deep breath and exhaled slowly. Worse than he had expected, or better? Did he need to start planning for the inevitable? Should he tell anyone at the unit, or would it get back to Arthur?

You can't go, old bean, Bryant would say when he found out, and find out he would because he always did. Not without me. I'm coming with you. You're not going off to have the biggest adventure of all on your own. He'd mean it, too. For all his appearance of frailty Bryant was an extremely tough old man; he'd just recovered from wrestling a killer in a snowdrift, and all he'd suffered was a slight chest cold. But he wouldn't want to be left behind. You couldn't have one without the other, two old friends as comfortable as cardigans.

Damn you, London, this is all your fault, May thought, shoving the letter into his pocket and striding off through the blustering rain toward the Charing Cross Road.

Chapter Three

End Times

Arthur Bryant blotted the single sheet of blue Basildon Bond paper, carefully folded it into three sections and slid it into a white business envelope.He pressed the adhesive edges together and turned it over, uncapping his marbled green Waterman fountain pen. Then, in spidery script, he wrote on the front:

For the attention of:

Raymond Land

Acting Chief

Peculiar Crimes Unit

Well, he said to himself, you've really done it this time. You can still change your mind. It's not too late.

Fanning the envelope until the ink was thoroughly dry, he slipped it into the top pocket of his ratty tweed jacket, checked that his desk was clear of work files and quietly left the office.

Passing along the gloomy corridor outside, he paused before Raymond Land's room and listened. The sound of light snoring told him that the unit's acting chief was at home. Usually Bryant would throw open the door with a bang, just to startle him, but today he entered on gentle tiptoe, creeping across the threadbare carpet to stand silently before his superior. Raymond Land was tipped back in his leather desk chair with his mouth hanging open and his tongue half out, faintly gargling. The temptation to drop a Mint Imperial down his throat was overpowering, but instead, Bryant simply transferred his envelope to Land's top pocket and crept back out of the room.

The die is cast, he told himself. There'll be fireworks after the funeral this afternoon, that's for sure. Bryant was feeling fat, old and tired, and he was convinced he had started shrinking. Either that or John was getting taller. With each passing day he was becoming less like a man and more like a tortoise. At this rate he would soon be hibernating for half the year in a box full of straw. He needed to take more and more stuff with him wherever he went: walking stick, pills, pairs of glasses, teeth. Only his wide blue eyes remained youthful. I'm doing the right thing, he reminded himself. It's time.

'Do you think he ought to be standing on a table at his age?' asked the voluptuous tanned woman in the tight black dress, as she helped herself to another ladleful of lurid vermilion punch. 'He needs a haircut. Odd, considering he has hardly any hair.'

'I have a horrible feeling he's planning to make some kind of speech,' Raymond Land told Leanne Land, for the woman with the bleached straw tresses and cobalt eye makeup who stood beside him in the somewhat risqué outfit was indeed his wife.

'You've warned me about Mr. Bryant's speeches before,' said Leanne. 'They tend to upset people, don't they?'

'He had members of the audience throwing plastic chairs at each other during the last "Meet The Public" relationship improving police initiative we conducted.'

They were discussing the uncanny ability of Land's colleague to stir up trouble whenever he appeared before a group of more than six people.Arthur Bryant, the most senior detective in residence at London's Peculiar Crimes Unit, was balanced unsteadily on a circular table in front of them, calling for silence.

As the room hushed, Raymond Land nudged his wife. 'And I don't think your dress is entirely appropriate for the occasion,' he whispered. 'You're almost falling out of it.'

'My life-coach says I should be very proud of my breasts,' she countered, 'so why shouldn't I look good at a party?' 'Because it's a wake,' hissed Raymond.'The host is dead.' 'Ladies and gentlemen!' Bryant bellowed so loudly that his hearing aid squealed with feedback.'This was intended to be a celebration of our esteemed coroner's retirement, but instead it has become a night of sad farewells.'

The table wobbled alarmingly, and several hands shot out to steady the elderly detective. Bryant unfolded his spectacles, consulted a scrap of paper, then balled it and threw it over his shoulder. He had decided to speak from the heart, which was always dangerous.

'Oswald Finch worked with the Peculiar Crimes Unit from its inception, and planned to retire on this very night. Everyone had been looking forward to the bash. I had personally filled the morgue refrigerator with beer and sausage rolls, and we were planning a big send-off. Luckily, I was able to alter the icing inscription on his retirement cake, so it hasn't gone to waste. "The funeral baked meats did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables," only the other way around, and with retirement substituted for marriage.'

'What's he talking about?' whispered Leanne.

'Hamlet,' said Land. 'I think.'

'Because instead of retiring,Oswald Finch died in tragic circumstances under his own examination table, and now he'll never get to enjoy his twilight years in that freezing, smelly fisherman's hut he'd bought for himself on the beach in Hastings. Now I know some of you will be thinking "And bloody good riddance, you miserable old sod," because he could be a horrible old man, but I like to believe that Oswald was only bad-tempered because nobody liked him. He had dedicated his life to dead people, and now he's joined them.'

One of the station house girls burst into tears. Bryant held up his hands for quiet.'This afternoon, in a reflective mood, I sat at my desk and tried to remember all the good things about him. I couldn't come up with anything, I'm afraid, but the intention was there. I even phoned Oswald's oldest school friend to ask him for amusing stories, but sadly he went mad some while back and now lives in a mental home in Wales.'

Bryant paused for a moment of contemplation. A mood of despondency settled over the room like a damp flannel. 'Oswald was a true professional. He was determined not to let his total lack of sociability get in the way of his career. True, he was depressing to be around, and everyone complained that he smelled funny, but that was because of the chemicals he used. And the flatulence. People said that he didn't enjoy a laugh, but it went deeper than that. In all the years I worked with him, I never once saw him crack a smile, even when we secretly attached electrodes to his dissecting tray and made his hair stand on end when he touched it.' Bryant counted on his fingers.' So, just to recap, Oswald Finch --- no sense of humour, no charm, friendless, embittered, stone-faced and bloody miserable, on top of which he stank. Some folk can fill a room with joy just by entering it. Whereas being in Oswald's presence for a few minutes could make you long for the release that death might bring.'

He paused before the aghast, silenced crowd.

'But --- and this is the most important thing --- he was the most ingenious, humane and talented medical examiner I ever had the great pleasure of working with. And because of his ability to absorb and adapt, to think instead of merely responding, Oswald's work will live on even though he doesn't, because it will provide a template for all those who come after. His fundamental understanding of the human condition taught us more about the lives and deaths of murder victims than any amount of computerised DNA testing. Oswald's intuitive genius will continue to shine a beacon of light into the darkest corners of the human soul. In short, his radiance will not dim, and can only illuminate us when we think of him, or study his methods, and for that I raise a glass to him tonight.'

'Blimey, he's finally learning to be gracious,' said Dan Banbury, the unit's stubby crime scene manager. 'I've never heard him be nice about anyone before.'

'He must be smashed,' sniffed Raymond Land, jealously turning aside as the others helped Bryant from his wobbly table. He glanced down at the white-and-blue-iced fruitcake that stood in the middle of the pub's canapé display. The inscription had read Wishing You the Best of Luck in Hastings, but Hastings had been partially picked off and replaced with a shakily mismatched Heaven.The iced fisherman's hut now had pearly gates around it, and the stick figure at its door had sprouted wings and a halo, picked out in sprinkles.

'I hope the cake has more taste than the inscription,' muttered Land, shaking his head in despair.

Nobody had expected the retirement party for the Peculiar Crime Unit's chief coroner to become a wake, but then life at the unit rarely turned out according to anyone's expectations. Oswald Finch had died, sadly and suddenly, in his own morgue, in what could only be described as extraordinary circumstances. Yet his death seemed entirely appropriate for someone who daily dealt with the deceased.

Raymond Land had never expected to stay on this long at the PCU. After all, he had joined the unit for a three-month tour in 1973, and was horrified to find himself still here.

Arthur Bryant and John May, the unit's longest-serving detectives, had been expected to rise through the ranks to senior division desk jobs before quietly fading away, but were still out on the street beyond their retirement ages.

Detective Sergeant Janice Longbright had been expected to marry and leave the force, perhaps to eventually resume her old job as a nightclub manager, but instead she had chosen her career over her husband and had stayed on.

The PCU itself should have been disbanded by now, but had successfully skated over every trap laid for it by the Home Office. Even Land had argued for the unit's closure behind his colleagues' backs, but had then surprised himself by fighting back in order to preserve it.

Life, it seemed, was every bit as confusing and disorderly as the PCU's investigations.

Now, the annoyingly upper-class pathologist Giles Kershaw was to be promoted into Finch's position in charge of the Bayham Street Morgue,which meant that the PCU was losing another member of staff.With grim inevitability, the Home Office would doubtless seek to use the loss as a method of controlling and closing them down. The oldest members of staff were destined for the axe. Land had given up hope of ever finding a way to transfer out.He had nailed his colours to the unit's mast when he had reluctantly supported his own staff and attacked his superiors. Now, those same superiors would never find him a cushy detail in the suburbs where he could quietly wait out the remaining years to his retirement.

Land sighed and looked about the pub's upstairs room. Plenty of officers from Albany Street,West End Central and Savile Row nicks, even ushers from Great Marlborough Street Magistrates Court had turned up for the wake, but the Home Office had chosen to show their disdain by staying away. Finch had upset them too many times in the past.

Sergeant Renfield, the oxlike desk officer from Albany Street, was watching everyone from his lonely vantage point near the toilets. Land headed over with two bottles of porter clutched between his fingers. 'Hullo, Jack,' he said, refilling Renfield's beer glass with the malty liquid.'I wondered if you'd show up to see Oswald off.'

'You bloody well knew I'd be here.' The sergeant regarded him with a baleful eye. 'After all, it's partly my fault that he's dead.'

'There's no point in being hard on yourself,' said Land. 'People working in close proximity to death face unusual hazards. It's part of the job.'

'Try telling that to this lot.' Renfield gestured at the room with his glass.'I know they blame me for what happened.' The sergeant had made a procedural shortcut that had been revealed as a bad decision in the light of Finch's death.To be fair, it was the sort of mistake that often occurred when everyone was under pressure.

'Actually, Jack, today isn't about you. Besides, you'll get a chance to have your say.'

Renfield looked anxious. 'You haven't already told them, have you? Have you said something to Bryant and May?'

'Good God, no. Call me old-fashioned, but I thought we'd get Oswald into the incinerator before I gave them the good news. Come to think of it, perhaps you should be the one to make the announcement.' Land patted the sergeant on the shoulder and moved away. He wasn't alone in disliking Renfield, who was a Met man, as hard and earthy as the ground he walked on. Renfield had no time for the airy-fairy attitudes of the PCU staff, and didn't care who knew it. Left alone in the corner of the room once more, he decided to concentrate on fitting sausage rolls into his mouth between slugs of beer.

Over at the bar, Arthur Bryant adjusted his reading glasses, held up the aluminium funeral urn and turned it over to examine its base. 'Made in China,' he muttered. 'A lightweight wipeclean screw-top final resting place. I suppose Oswald would have approved. But how quickly we sacrifice dignity for expedience, even in death.'

'Well, he didn't choose it for himself,' said John May. 'He'd have picked something less vulgar.He was always so thorough, and yet he decided to entrust his remains to you.'

'He knew I'd do the right thing,' said Bryant with a knowing smile.

'Which is?'

'I've been instructed to plant his ashes in a place that would annoy Raymond. I thought the little park behind Pratt Street would do nicely, because Land always goes there for a quiet smoke. I'm going to stick it right opposite the bench where he sits, so he'll have to keep looking at it. I've already had a word with the park keeper.'

'Do you think Oswald would want to be buried there?'

'Why not? It's handy for the office. He worked in the same place for fifty years. People don't like change, alive or dead.' Bryant lifted his rucksack from the floor to place the urn inside it, but changed his mind. 'One thing puzzles me, John. He didn't want floral tributes, but requested posthumous contributions for the Broad Hampton Hospital. He never mentioned the place before. I thought it might be where his old school pal was kept, but no. Maybe he has a family friend staying in there, some kind of debt to be honoured. He probably wouldn't have wanted to discuss the matter in life. It's an asylum, after all.'

'No,' replied May indignantly, 'that's exactly what it's not. It's no longer a place of confinement. Nowadays it specialises in advanced treatment and research into mental health care.'

'You know its sister hospital is the oldest psychiatric hospital in the world?' Bryant poked about among the canapés and thought about dipping a battered prawn. 'The Bethlem Royal was once known as Bedlam, famous for the ill-treatment of its patients. Visitors were given sticks so they could poke the loonies. Insanity used to be viewed as the result of moral lassitude, you know. Charlie Chaplin's mother and the artist Richard Dadd were both locked up in there. But I don't think Hogarth's ghastly engraving of the place is entirely to be believed. There were flowers and birdcages in its women's wards, and a few surprising instances of enlightened thinking on behalf of the doctors. It's been knocking around since the mid-thirteenth century and is still going strong, as part of the South London Trust.' Bryant removed a prawn-tail from his dentures and absently put it in his pocket. 'I don't trust this Mary Rose sauce, far too pink for my liking. Oswald told me he had no other living relatives. So why would he want us to give money to a mental hospital?'

'I really have no idea.'

May was a poor liar. When he glanced away at the floor, Bryant sensed there was something he had not yet been told about the deceased coroner.

Excerpted from The Victoria Vanishes by Christopher Fowler Copyright © 2008 by Christopher Fowler. Excerpted by permission of Bantam, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.