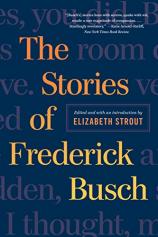

The Stories of Frederick Busch

Review

The Stories of Frederick Busch

W. W. Norton & Company deserves the thanks of anyone who loves an intelligent, well-constructed short story, for publishing this career-spanning collection of more than 30 of them from the grossly underappreciated Frederick Busch. Busch, who died in 2006 at age 64, taught creative writing at Colgate for nearly four decades and produced seven collections of short stories. Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Elizabeth Strout (OLIVE KITTREDGE; THE BURGESS BOYS) has selected nearly 500 pages worth of his best ones for this volume. In her generous introduction, after noting how the label “writer’s writer” frequently is attached to those, like Busch, whose careers combine literary craftsmanship and modest sales, she rightly observes that “any reader, whether they are a writer, or a lover of humanity, a consumer of literature for the sake of it alone, has a great deal to find here.”

Busch was a contemporary of writers like Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, Tobias Wolff and Andre Dubus II, once associated with the literary movement inelegantly named “dirty realism.” Like them, he shares a preoccupation with the predicaments of ordinary people, more focused on closely observed character studies and life’s barely noticeable turning points than dramatic plot twists. Though their circumstances are as varied as real life --- something that makes easy summary a challenge --- if there’s a dominant tone, here it’s one of regret. Whether it’s come about as a result of divorce, death or abandonment, many of Busch’s characters seem to understand that happiness is forever destined to lie just beyond their grasp.

One of the most affecting stories in that vein is “Ralph the Duck.” Its protagonist is a college security guard and Vietnam veteran, one of whose fringe benefits is his ability to take one course a semester, assuring “graduation in only sixteen years.” It’s only in the course of his rescue of a suicidal student that we learn the source of his private grief. “Dog Song” features a minor judicial officer who finds himself in the hospital, desperately trying to recall the circumstances of the automobile accident that’s landed him there.

"Busch is a confident prose craftsman; he doesn’t dazzle with experimental structures or other striking effects, but instead is content to hammer out one sturdy sentence after another."

“Reruns,” the story of a psychiatrist whose estranged wife has been taken hostage in Beirut, is an exceptionally powerful one. In it, he watches a grainy tape sent by her captors, “my wife on reruns, available as starkly as this, and to strangers.” Another story that reveals Busch’s skill at creating dramatic tension is “Bob’s Your Uncle,” where a troubled teenager, the son of the narrator’s former lover, travels from England to America for an unsettling visit with the man and his wife, who stands, in the story’s climactic paragraph, “between men gone wrong, or boys who hadn’t turned out right.”

Though many of the stories are set in the small towns of upstate New York, where Busch lived most of his life, they’re leavened by a few tales that take place in and around New York City, where he was born. In “Vespers,” a woman returns with her Midwestern lover to her Flatbush neighborhood, where she and her brother “had grown up, sometimes even together.” The narrator of “The Lesson of the Hotel Lotti” has “composed some recollections, for the sake of sentiment,” of her mother’s affair with a successful Manhattan maritime lawyer.

Busch is a confident prose craftsman; he doesn’t dazzle with experimental structures or other striking effects, but instead is content to hammer out one sturdy sentence after another. Where his mastery is most evident is in the opening lines of so many of these stories, thrusting us into that moment, identified by the great Irish short story writer Frank O’Connor “after which nothing else is ever the same.” A few examples, each one a model of concision, suffice to reveal his talent:

“It began for me in a woman’s bed, and my father was there though she wasn’t.”

“Rudy made me promises, and they came true.”

“Duane and I don’t talk about how she killed herself or where.”

“Did I tell you she was raped?

“I loved his mother once.”

Couple these striking beginnings with a facility for realistic dialogue, an ability to sketch a scene in efficient strokes, and a keen understanding of human psychology, and you instantly appreciate why Busch was held in such high regard by his fellow writers.

At any given moment in the literary world, it seems someone either is lamenting the death of the short story or trumpeting an imminent revival. Reading Frederick Busch renders those predictions irrelevant. In “The Floating Christmas Tree,” an essay in Busch’s 1999 collection A DANGEROUS PROFESSION, he claimed he wrote “for love, because of a compulsive need, out of a requirement that I cannot shake: that I justify my time on the earth by telling stories. That’s what I have to do. I have to do it.” These stories, with their deep empathy for humanity in all its beauty and pain, show how that time was more than justified.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg on December 20, 2013

The Stories of Frederick Busch

- Publication Date: March 30, 2015

- Genres: Fiction, Short Stories

- Paperback: 512 pages

- Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

- ISBN-10: 0393350762

- ISBN-13: 9780393350760