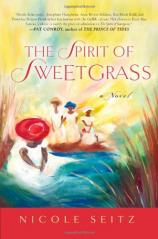

The Spirit of Sweetgrass

Review

The Spirit of Sweetgrass

In her engaging debut novel, THE SPIRIT OF SWEETGRASS, Nicole Seitz introduces readers to the rich and diverse world of South Carolina’s Lowcountry Gullah culture, interspersing themes of faith, forgiveness and the importance of family throughout.

Using first-person narrative, Seitz introduces readers to 78-year-old Essie Mae Jenkins, a widow who sells her hand-woven sweetgrass baskets at a highway roadstand. Essie misses “Daddy Jim,” her husband who died in three short months from lung cancer: “When Daddy Jim died, my whole life just flip-flopped like a catfish dying on the dock. Right about then’s when I took up basket making again.” But with her husband gone and income sporadic at best, Essie is in trouble. She owes $10,000 in taxes on her home, and selling baskets won’t even begin to cover it.

The known world and the supernatural mingle throughout the novel. In the first half, this mostly consists of Essie talking to Daddy Jim as if he is alive. “Jim, what I’m gonna do? Things is fallin’ in all over me.” Essie’s daughter, the unlikable Henrietta, believes that the answer is for Essie to move into a retirement center. But Essie clings to her home, and to a way of life in the Gullah culture that seems on the verge of vanishing.

She has other disappointments as well. Essie’s beloved grandson, EJ, seems intent on marrying a white girl. And Essie’s matchmaking talents are seemingly wasted on the good-looking Jeffrey, who doesn’t appear interested in women. Most challenging is her relationship with the bitter Henrietta, whose angry spirit widens the deep divide between her and her mother.

Not all writers can handle regional dialect well, but Seitz does an exceptional job here. Although the dialect is heavy, it reads smoothly and enhances rather than detracts from the narrative.

Those readers who enjoy a supernatural, suspend-disbelief component to their fiction will enjoy the second half of the novel, in which Essie dreams that she has died and gone to heaven. There, she meets her ancestors and reunites with those loved ones who have passed on. Seitz paints this heavenly reunion with delightful imagination: “In the Lowcountry, when we would have family reunions, we’d pull everybody together and have a big ol’ oyster roast with lots of drawn butter and fried shrimp caught fresh that day. Folks I ain’t never seen before from all over would come out the woodwork…. Well, now take that and multiply it by a hundred. That’s how crazy it is here in heaven.”

Heaven, she finds, is “like everythin’ I ever ‘magined and then some.” Essie’s “mama” makes her okra soup and cornbread, and Essie and her husband, Daddy Jim, even engage in a little lovemaking. (Is there sex in heaven? Seitz says yes!) And in the afterlife, Daddy Jim says “…ain’t no such thing as black and white folks. If somebody’s done made it up to heaven, they get to glowin’ like a rainbow full of all sorts of colors.”

Heaven holds more surprises, as when (in a subtle and poignant pro-life theme) Essie discovers she has a granddaughter who Henrietta aborted and no one else knew about. Although this second half of the novel is less absorbing than the first, it will still hold readers’ interest. The weakest portion of the novel may be when Essie and her ancestors return to earth to crash the Sweetgrass Soiree and try to save the basket-weaving culture from the evil spirits conjured up by Henrietta’s “hoodoo” or voodoo that threatens to destroy it.

Despite this, Seitz’s imaginative story is an absorbing and even educational introduction to the Gullah-Creole way of life. Readers will hope to hear more from this promising novelist.

Reviewed by Cindy Crosby on March 6, 2007