Excerpt

Excerpt

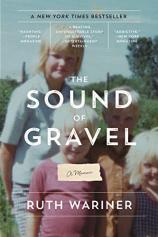

The Sound of Gravel: A Memoir

Prologue

The room feels crowded, the attention overwhelming. A swirl of women in chocolate-and-sage dresses surrounds me. They fasten the satin-covered buttons on my gown, adjust the ivory flower in my hair. When they’ve finished their fussing, I stare at my reflection in the mirror, centering my veil at the crown of my head. Over my shoulder, I see my sisters perched on the edge of the bed behind me.

“Are you ready?” I ask.

“Ready.” the three look up at me; stand up tall and straighten the hems of their dresses at their knees.

They might be ready, I think, but I’m not sure I am. I grew up dreaming of this day. I fantasized about the handsome prince who would carry me off on his white horse, whisking me away into the sunset. And now here I am, convincingly regal in my lace gown and shiny ivory-and-silver slippers. There is a flowering-pink dogwood tree right outside the window of my dressing room, just as there should be, and birds are actually singing in it. I hear their song as I give myself a final once-over.

It is a wedding day just like every bride dreams of, at least until I climb the steps leading to the next room, where my large, loud family waits for me impatiently.

I feel my heart racing in my chest, the blood pulsing in my neck. My face turns warm, and I become flushed. It must be nerves, I tell myself. But I know it’s more than that. I know what I will see when I turn that knob and walk through the doorway.

PART I

THE PROMISED LAND

1

I am my mother’s fourth child and my father’s thirty-ninth. I grew up in Colonia LeBaron, a small town in the Mexican countryside 200

miles south of El Paso, Texas. the colony, as we called it, was founded by my father’s father, Alma Dayer LeBaron, ather God sent him a vision. In that vision, my grandfather was walking in the desert when he heard a voice that foretold of a place that would one day be populated with trees dripping with fruit, wonderful schools, beautiful churches, bountiful farms, and happy, faithful people. My grandfather had grown up in a fundamentalist Mormon family, and he always believed in the polygamist teachings of Joseph Smith. When the vision came to him, he knew he needed to move to Mexico and establish a community that would be a beacon of hope, an example of what comes from living righteously.

My grandfather and grandmother LeBaron established the colony in 1944, and other polygamist families soon followed. Before long, the dry Mexican earth was cleared of mesquite and planted with orchards, pecan trees, and gardens. Cattle were brought in to be raised, and the town grew and flourished. My grandfather boldly predicted that someday people from all over the world would make pilgrimages to the town, and that the work being done there would be of the utmost importance to the realization of God’s kingdom on earth.

My grandfather died before I was born, but I entered childhood in the community that was his legacy. I took my first steps on the dirt roads that ran through the small farming community, tiny rocks and dry dirt getting stuck between my toes and piercing the soft soles of my feet. The trees my grandfather planted offered the shade that first cooled and protected my pale, freckled skin from the harsh desert sunlight. I ran through the peach orchards with my siblings, drank fresh milk from the cows on our dairy farm, and ate vegetables from the gardens my grandfather had first seen in the vision God sent him. My family and I always tried our best to be the happy, faithful people God had promised would come to populate the colony.

“Ruthie,” Mom yelled to me from the hallway, “Get up quick. We’ll be late for church.” I rubbed my eyes and pulled myself out of the small bed I shared with my sister Audrey. Even though she was five years older than me, she wore a cloth diaper that othen leaked during the night. I took a towel and dried my damp legs as Mom told me to hurry and get dressed. “There’s not enough time to get Audrey and your brothers ready,” she hollered. “Matt’ll stay here and watch the kids and you’ll come to church with me.”

At five years old and with four siblings, having Mom’s undivided attention was a rare privilege. I threw my pink cotton dress over my head and tried to run my fingers through my tangled hair. Mom put my baby brother Aaron in his playpen and called to my older brother Matt, asking him to keep an eye on things. Then she grabbed my hand and pulled me along behind her. I scurried to keep up, taking three steps for every one of Mom’s long strides, happy to have been the one chosen to accompany her. The cool morning air was pungent with the scents of the freshly irrigated alfalfa fields, the dairy cows behind our house, and Mexican sage brush.

Every place in LeBaron was within walking distance of every other, and each unmarked, unnamed dirt road led to the church at the center of the colony. As Mom and I made our way to the simple, single-level adobe structure, pickup trucks sped past us, stirring up clouds of dust in their wake. As we got closer, we heard the strains of a piano and singing voices flowing through the two black wooden doors. “We’re already late, Ruthie,” Mom said, looking down at me through the plastic frames of her glasses. I was used to hurrying at her side; we were always late to everything.

Mom and I rushed past the few saddled horses tied to the crooked, wooden posts that held up the barbed-wire fence surrounding the churchyard. The singing voices grew louder as we entered the church and Mom searched the large, white-walled room for empty seats. The black wooden benches were full of congregants—women in Sunday dresses, nude nylons, and high heels, men in cowboy boots and Western shirts tucked into tight jeans under leather belts with big, silver belt buckles.

We crowded into open seats as Mom pulled out a hymn book from a wooden pocket on the back of the bench in front of us, cocked her neck forward, and squinted to peek over someone’s shoulder to find the right page. I loved standing next to her in church. I was mesmerized by her eyelashes, which were usually so blond that I couldn’t see them, but on Sundays she wore light brown Maybelline mascara and pearl-pink lipstick that she dabbed over her lips and onto her cheeks.

After playing three hymns, the pianist retired to a pew as a man stepped forward to utter a prayer, which a second man translated into Spanish for the Mexican parishioners on the opposite side of the building.

“Make sure no one can see your underpants, Sis,” Mom whispered, straightening the hem of my dress over my knees as the elder called for someone to come up and offer a testimony.

Lisa, my stepfather Lane’s sister, walked slowly, her head held high, the wooden heels of her strappy sandals tapping hard against the floor. She stood tall and spoke with confidence. She told us how thankful she was for all the blessings that our Heavenly Father had given her. She talked proudly about her devotion to the cause. She said that even though it was hard to share her husband with her sister wives, even though she sometimes felt jealous, she knew in her heart that she was obeying God’s will by living polygamy. Lisa said she loved being a mother and that she was grateful to be the caretaker of the beautiful spirits the Lord had sent her. Often she thanked Him for giving her a good, righteous man to father her children. “After all,” she said, “it is better to have ten percent of one good man than to have one hundred percent of a bad one.” the women of LeBaron were always saying that, and Mom always nodded her head in agreement.

As Lisa spoke, I gazed at the three large, black-and-white photographs that hung behind the red-carpeted pulpit. The middle photo, bigger than the other two, was of a man with a round, shiny forehead and a square jaw. His dark hair was combed straight back, a few thin strands stretched flat over a bald spot. He wore a crisp white shirt buttoned to the top with a dark tie and matching jacket. His full lips were closed, and he didn’t smile, but he had kind and happy eyes that stared out with confidence and authority.

This was my father. He had been the prophet of our church. He died when I was three months old, and no matter how many times I begged Mom to tell me about him, I could sense that there was a lot about my dad that I’d never know. Did he like playing board games and hiking in the Mexican hills like me? Did he like chocolate ice cream or did he prefer my favorite, old-fashioned vanilla? Everyone always said my dad was the kindest, most faithful, God-fearing man they knew. I wished I could remember what life had been like when he was alive.

After the service ended, Mom and I walked back to the farm slowly, relishing the warm sun on our shoulders and stopping to say hello to our friends and neighbors along the way. Very few of the homes in LeBaron had telephones and Sundays were a good chance for everyone to catch up. Mom stopped to talk to Lisa, who was not only my step-dad’s sister, but she had also been one of my dad’s wives. Even though she was much older than Mom, they were still good friends.

“I loved your testimony this morning,” Mom told Lisa. “It really inspired me.”

“Thank you, Kathy. Why don’t you bring the kids over next Saturday and we can have dinner at my house?” Lisa smiled, her skin wrinkling around her eyes.

“That sounds great,” Mom said. “I’ll bring dessert.”

Mom and Lisa said their good-byes and Mom grabbed my hand, pulling me toward home. “We’d better get back to Audrey and your brothers,” she said. The streets were quiet as we walked past adobe homes with spacious yards and gardens surrounded by barbed wire fences.

The farther we got from the center of town, the more spread out the neighborhood became. Eventually we walked past our neighbor’s farm and reached the tall earthen banks of the reservoir. Five hundred feet long and fifty feet wide, the reservoir brought water to our irrigation ditches and those of the neighboring farms. Young willow trees lined its perimeter, and we could usually hear families of frogs croaking from its banks. It had been built as a community water supply, but it served as the colony swimming pool too. Adults and children came from all over to frolic and swim in the open-air tank, diving into it from a giant pipe that pumped freshwater from a deep well.

Our house was on the other side of the reservoir, at the end of a long gravel driveway. A tall barbed-wire fence surrounded my stepfather’s property. Unlike some of the houses closer to town, ours didn’t have any flowerbeds or a lawn. Mom was never able to get anything to grow. Except for her Volkswagen Microbus, which was usually broken and parked beside the kitchen door in the side yard, the house sat stark and solitary against the dry Mexican landscape.

An irrigation ditch of steadily flowing water ran along the front of our property. My stepfather had dug out the ditch at the beginning of our driveway so that it was wide and shallow enough for cars to drive through without wetting a car’s engine. But when we weren’t in a car, we had to leap across the ditch’s narrow edge to get to our house.

Mom held my hand and we jumped across. As we landed on the opposite edge, clumps of wet earth crumbled underneath our feet and splashed into the running water.

When we got inside, Mom went to nurse my baby brother, Aaron. I pulled out my Disney coloring book and stubby crayons and made myself comfortable on the living room floor. Matt and Luke went out to play, while my older sister, Audrey, sat on the couch pulling at the cotton threads in her shirt, staring off into the distance, a quiet moaning sound coming from the back of her throat.

“Hush, Sis,” Mom said, patting Audrey on the shoulder as she passed back through the living room. “Ruthie, come help me with these beans.” I jumped up from the floor and hurried to Mom’s side. She pulled a large gunnysack of pinto beans from the corner of our small, square kitchen. “It’s important for you to learn how to cook. You’ll need to know what to do when you’re married and have your own kids.” She spilled a pile of the speckled, brown beans onto the kitchen table. “When I married your dad, I didn’t know how to make beans or anything else because my mom never showed me.” I climbed up onto a chair and began imitating Mom’s movements, carefully taking a small handful of pintos and spreading them out in front of me.

“How old were you when you and Dad got married?” I didn’t much care for boys, but I knew that I would get married one day. Celebrations were an important part of life in LeBaron. We had lots of rodeos, horseback rides, campouts, bridal showers, baby showers, birthday parties, and Friday-night square-dance lessons at the church. But weddings were the most important.

“I was seventeen.” Mom scanned the pile of beans from behind her thick glasses, shooing away the flies that had infested our kitchen. My siblings and I loved hearing the story about how, on one of my dad’s mission trips to Utah, he climbed to the top of a mountain where he was visited by several resurrected prophets, including Jesus, Moses, and Joseph Smith. They told my father that he had been selected to lead a congregation with Colonia LeBaron as its Zion. Out of this visitation, Dad’s church, the Church of the Firstborn of the Fulness of Times was born.

My father believed that polygamy was one of the most holy and important principles God ever gave His people. He preached that for a man to reach the Celestial Kingdom—the highest level of heaven— he had to have at least two wives. If a man lived this principle, he would become a god himself and inherit an earth of his own, one just like our earth. Women who married polygamists, loved their sister wives, and had as many children as they could would become goddesses, which meant that they were their husband’s heavenly servants. Salvation came from freeing oneself and others from the moral turpitude of Babylon. My dad had visions in which God foretold the destruction of the United States, which my dad believed was a modern Babylon. That’s why he ended up doing much of his missionary work in the Babylon among Babylons: Las Vegas. That was where he first noticed my mom.

“When we were living in Las Vegas, your dad asked Grandpa if he could court me.”

“Court you? What’s that?”

“It means that he wanted to get to know me so that he could marry me.” Mom slid more beans across the tabletop. They sounded like plastic pieces moving over a checkerboard. “I was fourteen years old when I first heard about your dad. We were living in Utah, and your dad and his brother Ervil were on a mission trip there. One day, they put a pamphlet on Grandpa’s windshield. Grandpa saw the pamphlet, took it out from under the windshield wiper, and brought it home.” Mom paused to take another handful of beans from the sack. She spread them out on the table and picked out the rocks and dried weeds before sliding the beans into a pot on her lap.

“That pamphlet changed my life. Not long after Grandpa read that paper, he started asking questions at church, questions about Joseph Smith’s original teachings and why polygamy was no longer a part of the Mormon way of life. Not long after Grandpa started asking those questions, he was excommunicated from the Church. That’s when we moved to LeBaron.

“When the bishop made your grandpa leave the Church, Grandpa took it as a sign from God that your dad was right, that the LDS Church had lost its way. He bought property in LeBaron and moved us down here.”

“Did you like moving to LeBaron?” I asked, trying to imagine a time before my mom lived on the colony.

“Well, Sis, it was a real shock for me. I really missed my friends in Utah. I had always been shy, so it was hard for me to move to a new place.” Mom looked down at her pile of beans with a somber expression. “But our time here didn’t last long. It was too hard for Grandpa to support us in Mexico, just like it is hard here for a lot of people even now. So Grandma and Grandpa eventually moved us to Vegas. A lot of your dad’s followers were livin’ and workin’ as builders and painters in Vegas. Grandpa and Grandma bought a diner there and called it the Supersonic Drive-In. I worked there as a waitress—a waitress on roller skates.”

“And that’s where you met my dad?”

“Well, I knew about your dad before he first saw me at the diner. Grandpa had been going to your dad’s church for about four years by then. I had a dream about marrying your dad and I told your grandpa about it, so he said yes when your dad asked to court me. Our wedding was just a few months later. I became your dad’s fifth wife in a small ceremony right here in a living room in LeBaron.”

In our dark, bare-walled kitchen far from the lights of Las Vegas, I watched Mom’s lightly freckled arm slide another clean pile of beans off the edge of the table into the pot and thought about how different her life was now. Mom had five kids—my older sister, Audrey, my older brothers, Matt and Luke, and the baby, Aaron. Mom always seemed worried and exhausted. I liked imagining her skating around a diner, serving hamburgers to my dad.

“But, Mom, didn’t you like Las Vegas? Why did you want to leave?”

The sound of the hard beans hitting the metal pan echoed through the kitchen. “Of course I loved parts of our life in Vegas, Ruthie. I made lots of friends there and I loved music and dancing, but I felt like I wanted more. That’s when I started to like your dad. I was only seventeen, but he inspired me to live a life for our Heavenly Father’s purpose. I wanted to be a part of his big family and help with his work in the church.”

Mom stopped cleaning the beans for a moment, sat back in her chair, and rested her thick brown hair against its back. She always cut her hair herself, and always just above her shoulders, in short, feathered layers. She smiled as a faint whiff of fresh cow’s milk drifted through the kitchen window. It mingled with the scent of the green alfalfa fields outside and the cheese curds we kept in a pan on the stove. Except for when it rained, when all we smelled was wet dirt from the adobe bricks and stucco that made up our small, five-room house, the kitchen always smelled like the little mice that scampered along the walls, the cows in the fields outside, and the Mexican sagebrush on the nearby mountains.

“You know, Ruthie, your dad was the most humble man I’d ever met. He always practiced what he preached, and he never turned away anyone when they came to him for help.” Mom thought for a moment. “When he asked me to marry him, it was the happiest day of my life. We were sittin’ alone in a car at night. He kissed me and it felt right. Even though he was twenty-five years older than me and already had four wives, I knew I was makin’ the right choice. I had never wanted to marry any other man till then.”

Mom swept the last pile of pintos toward her with swollen, stubby fingers; she chewed her nails down to the quick, her cuticles red and raw. “Your dad and I hadn’t been married for very long when it was my turn to have him spend the night. You know, I only got to see him once a week, and then only if I was lucky. With five wives, his mission trips, and his work, there just wasn’t time. Anyway, when it was my turn to have him over, all we had to eat were pinto beans. So I put some water in a pot and then I filled it all the way up to the top with beans. To the top. I didn’t know that beans swell up!” She paused and laughed at the memory. “The beans started boilin’ and swellin’ up and overflowin’ out of the pot. I had to pour half of them into other pots. By the time I was done, we had three full pots of beans, and I had to throw half of them out because they soured before we could eat ’em!” She laughed again and flashed her hazel eyes at me, which dazzled with speckles of green when she was happy and turned the color of mud when she wasn’t. “Bein’ a housewife was all new to me. ’Cause nobody ever taught me how, Ruthie. That’s why it’s important that you start learnin’ now.”

Mom pulled herself out of her chair to pour herself a glass of water from the pitcher on the counter. I couldn’t imagine a time when she didn’t know how to cook. I couldn’t imagine a time when she didn’t have kids. “But, Mom, if Grandpa gave my dad permission to court you, why aren’t he and Grandma still a part of our church?”

“Well, Sis, everything changed after your dad died.” Mom took in a deep breath and shook her head. “It was just such a mess. Ather your dad died, so many people turned their backs on him and left the church. Grandpa and Grandma lost faith and so did Aunt Carolyn and Aunt Judy. They all sold their property in LeBaron, moved to the States, and didn’t come back.”

“Is that when we went to live in San Diego?”

“That’s right. I took you and Audrey and Matt and Luke to go live with Grandma and Grandpa for a while. But I knew I wanted to come back to LeBaron. This is where you kids belong.”

I focused on my little pile of beans, continuing to separate them from the dirt and rocks that were in the bag. I didn’t remember living with Grandma and Grandpa, but there was a part of me that wished we were still there. I knew we were doing the right thing living God’s purpose in the colony, but I envied my cousins in California. They lived in nice houses with bathrooms and they always had new clothes and toys. Sometimes I’d lie awake at night thinking about what it would be like if Mom had never married my stepfather and had never brought us back to LeBaron.

Mom met Lane when I was three and she became his second wife a few months later. My grandparents and aunts were invited to the wedding, but they didn’t believe in polygamy anymore so they didn’t go.

Mom said Lane was handsome. He had sandy-blond hair, olive skin, and light blue eyes. He wore his hair slicked back behind his ears with long, perfectly trimmed sideburns. He had been an apostle in my dad’s church, which is what my mom said she loved most about him. The people of the colony called him Brother Lane.

After they married, Mom moved us onto Lane’s eleven-acre farm. Our little house had two bedrooms and one unfinished bathroom that Lane was always promising he’d fix. Until he did, we used a wooden outhouse in the backyard. Lane’s first wife lived in another adobe house a quarter of a mile from ours, at the opposite edge of the farm. Mom’s house was separated from her sister wife’s by a barbed-wire fence, several acres of alfalfa, and a small peach orchard. We didn’t have electricity—we were too far out of town, and power hadn’t yet reached that far into the countryside—but Lane said it was coming.

Lane was the only father figure I’d ever known, but I never liked him. Whenever he was at church or with other churchgoers, he was happy and friendly, always offering to help them fix their cars or their broken appliances. But when he was at home, he was always cross, threatening to spank me if I cried for Mom’s attention. Mom never spanked or hit us, and Lane’s temper scared me.

Two years after Mom and Lane were married, she gave birth to my brother Aaron, who I adored instantly. Having a baby around was like having a new pet. Right after Mom came home from the hospital, she told me I could be her little helper, and I was thrilled. Matt and Luke went to the Mexican public school across the highway from LeBaron, leaving me at home on the farm with Audrey, Mom, and baby Aaron. Even though she was the oldest, Audrey didn’t go to school. Mom said Audrey was too much for the teachers to handle. I hated being stuck at home with my sister, but I loved helping Mom take care of my baby brother.

Her beans all clean, Mom stood up and scooped my little pile of pintos into her pot. She knelt down underneath the wood-framed window and filled the pot with water from a spigot that sprouted right out of the cement floor. Mom put the pot on the propane stove and lit the burner with a match. The stovetop hissed and the air smelled like sulfur. Mom stirred the beans a couple of times, then went to go check on Audrey, telling me to watch to make sure the pot didn’t boil over.

I sat in the kitchen thinking about how different my life would be if my dad hadn’t died. If he were still alive, Mom would be happy and would stop worrying all the time about how much it cost to feed all of us and how Audrey seemed so troubled. If my dad hadn’t died, maybe my grandparents would still live in the colony with us. I just couldn’t understand why my dad had been killed. I knew my uncle Ervil had him shot. Everyone in the colony knew that. Ervil and his followers sent lots of letters to our church elders threatening to kill more people and bomb the town. Mom said that Uncle Ervil was wanted by the FBI and that they had people looking all over Mexico and the United States for him. Each time we got a new threat, Mom would tell us to keep the doors locked. “And if I’m not home and you hear gunshots and explosions,” she always said, “take your baby brother and run to the peach trees, cover him, and lie down in the dirt so no one can see you.” Uncle Ervil was like a ghost haunting us. Knowing that he and his followers were still out there terrified me. Would Ervil come back for me? And what would happen if he murdered my mom the way he had murdered my dad?

The Sound of Gravel: A Memoir

- Genres: Memoir, Nonfiction

- paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: Flatiron Books

- ISBN-10: 1250077702

- ISBN-13: 9781250077707