Excerpt

Excerpt

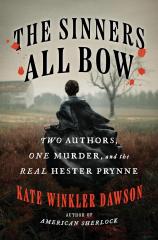

The Sinners All Bow: Two Authors, One Murder, and the Real Hester Prynne

CHAPTER ONE

The Durfee Farm

It was July 1, 1833, and the moon was just beginning to rise over the small town of Tiverton, Rhode Island. Catharine Read Arnold Williams stepped onto the wooden front porch and rapped on the door of the old home. It swung open, and a tall, thin man in a top hat greeted the writer, steeling himself for what he was certain would be a solemn visit.The man who answered the door, John Durfee, nodded respectfully to Catharine as she stood in the darkness. The farmer was known for his hospitality, and Catharine was familiar with his reputation. She was grateful that he had agreed to this meeting, morbid as it seemed. Both hoped to gain some understanding of what had happened on his farm the previous December. Durfee closed the door and stepped outside.

The thirty-five-year-old Durfee was an important, anxious witness-he had been the first person to find Sarah Maria Cornell's body that cold day half a year earlier. Catharine was determined to record Durfee's story accurately, so she reported to his farm that night for a tour.

This property was owned by Richard Durfee II, John's seventy-five-year-old father, who was a well-liked deacon and a retired captain with the Rhode Island militia. But it was John who ran the day-to-day operations. John Durfee was a profitable farmer, a justice of the peace, a widely respected town councilman, and a member of one of the most influential families in the area. Because of Durfee's seemingly sincere benevolence, the town leaders had appointed him "Overseer of the Poor." The overseer, a position originally created in England and later adopted by governments in the fledgling American colonies, was tasked with protecting the destitute in their parishes. Traditionally, the overseer would control a small budget for this purpose funded by collecting a tax from residents, but his duties also included distributing food and money and managing the local poorhouse.

As the pair stood together, Catharine inquired about John's family. His father, as well as his mother, Patience, would remain inside the house this evening, along with John's wife, Nancy, and their six children. The Durfee family had been in this area since the mid-1600s, beginning with Richard Durfee Sr., a descendent of several passengers on the Mayflower. Eventually, John's father married Patience Borden-a member of the later infamous Borden clan. (That family plays a prominent role in this story too, as you'll read later.) The Durfees and the Bordens, Catharine wrote, were two of the three families who had established Tiverton.

"The land in this vicinity belonged principally to the families of Borden, Bowen, and Durfee," she wrote in her 1833 book, Fall River, about this tragedy, "three families from whom the principal part of the stationary inhabitants sprung." It was a prosperous, fertile area; "so flourishing has business been there, that there is scarce a mechanic, trader, or even labourer, who has been there for any length of time, who has not acquired an estate of his own," Catharine wrote.

The Durfees and the Bordens would remain pillars of the community for generations. But all families are flawed, and some are plagued with characters with a penchant for brutality. The Bordens, who would come to infamy a few generations later when Lizzie Borden was tried and acquitted of the infamous axe murders that killed her father and stepmother, were clearly not immune to violence.

John Durfee, by all accounts, was prosperous, compassionate, and altruistic, a rare intersection of traits in the 1800s. It was important to Catharine and me to establish both Durfee's reputation and his apparent character because he had been a crucial witness-he had sounded the alarm about Sarah Cornell's death.

Catharine Williams was determined to record everything involving this case, including an extensive interview with John Durfee. The farmer described what he had discovered that frigid December morning. Durfee needed coaxing to recall such a traumatizing sight. He might have felt reticent because such horrid details surely would offend his guest's feminine sensibilities, yet he responded to her questions candidly, starting with a trip he'd taken with his horses early that day.

"On the morning of the 21 of December," began Durfee, "I took my team to go from home to the river, and passing through a lot about 60 rods from my house."

He descended the hill, careful to avoid burrow entrances dug by gophers and groundhogs the summer before. As Durfee approached a haystack, less than a quarter mile from his home, he gasped. "When I arrived within ten yards of the haystack, I discovered the body of a female hanging on a stake." Suspended by a cord, swaying slowly in the wind that blew from Mount Hope Bay, was the body of a young woman. Sarah Cornell was dressed in a long black cloak; her shoes were laid neatly on the ground. In the dim light of the sunrise, he could see that her short, dark hair was frozen to her face and covered in frost. John Durfee cried out and three men responded, including his father, Richard. The woman was young, attractive, and dead-but that's all Durfee knew at the time. The farmer told Catharine that he had never seen the woman before. As the sun began to illuminate the yard, Durfee braced himself.

"After taking more notice how she hung, I attempted to take her from the stake by lifting her up and slipping the line," said Durfee. "I found I could not well do it, at arm's length, and my father said, 'cut her down.' One handed me a knife, and I cut her down, and let her down."

Her body slumped; the cord was still wrapped tightly around her neck.

"I then went after the coroner," Durfee said, "and brought him to my house."

As the first person on the scene, Durfee wasn't just a witness-he was also a de facto investigator. He had initiated his own inquiry by collecting valuable evidence, and the picture that he and the investigators painted was a disturbing story, one Catharine was at the farm to hear about firsthand and examine further.

But first: safer subjects. That evening in 1833, Catharine began peppering John Durfee with queries about the property and its history. He replied as she jotted down notes. He resided on his 57-acre family farm on the main road of Tiverton, about a half mile from the Massachusetts border, across the water and less than two miles from the factory village of Fall River. As I noted earlier, that part of Tiverton was renamed Fall River, Massachusetts, about thirty years later.

The town was located on the Quequechan River, the last tributary at the mouth of the Taunton River, which made it a perfect spot to take advantage of the burgeoning industrial revolution that was sweeping across New England and reshaping the economy and landscape. The river was slow moving, even stagnant, except near downtown Fall River, where it flowed quickly down into Mount Hope Bay-the perfect fuel for textile mills and ironworks.

"Starting as early as 1811, cotton and woolen mills were built and put into operation," reported the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. The Durfees were at least partially responsible for Tiverton's growth as a mill town.

Water is featured in both Sarah Cornell's story and that of Hester Prynne. "Fall River can be understood in relation to . . . The Scarlet Letter," wrote Shirley Samuels in Reading the American Novel, 1780-1865, "as a narrative about an itinerant female laborer whose restlessness and employment depends on the vagaries of water. As the river waters that turn the mill wheels rise and fall, so does the employment of factory girls at the mill's ebb and wane."

Working women in the mid-1800s often needed to be near water. Joseph Durfee had built a simple spinning mill in the area at the turn of the century, and through the first few decades of the 1800s that holding had grown to contain even more mills. As the family's wealth increased, so did their influence. By 1833, Richard Durfee II's farm was a vast estate boasting a fantastic view of Mount Hope Bay-a clear symbol of their wealth and influence. The Durfees remained so important to the area for generations after that eventually a high school was named after them, as was a street in the town. There is still a mill complex in Fall River that bears the Durfee name, as well as a house designated as a historical home. The Durfees were Fall River and Tiverton royalty. Catharine Williams described their land at the time:

"Fall River, which in 1812 contained less than one hundred inhabitants, owes its growth and importance principally, indeed almost wholly, to its manufacturing establishments: which, though not splendid in appearance, are very numerous and employ several thousand persons collected from different parts of the country."

All these mills required workers, and towns like nearby Fall River began attracting men and increasingly women from the surrounding rural landscape. Women, in particular, were deemed well suited for mill work, because they tended to work hard without complaint; they also drank infrequently, mostly because they were tightly supervised in their boardinghouses. And many came from strict religious households, which meant reverence to men was mandatory. Most "female operatives," as women mill workers were called, were compliant, and if they weren't, they were forced to move on.

Sarah Cornell had been in many ways the ideal prototype for the female mill worker: husbandless, without a child, and untethered to her parents. She could toil for long hours without the need to tend to a family. Sarah was also a proficient weaver, seamstress, and tailor. The thirty-year-old had been professionally trained by other women in her youth, and by the time she reached the Fall River mills, she had logged many years of mill-work experience. Throughout her twenties, Sarah had traveled from village to village across New England, plying her trade year-round with few holidays and little respite. Anthropology professor David Richard Kasserman, author of the 1986 academic book Fall River Outrage, discovered that Sarah had moved more than sixteen times in twelve years to various jobs around Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Yet this sort of movement was not necessarily unusual for a woman like Sarah. Factory work was often seasonal, and workers might be shifted to and from mills if owners decided to downsize.

As America rapidly expanded in the first few decades of the 1800s, factories emerged in cities and towns all along the eastern coast, transforming their owners into millionaires. Smoke spilled from the factory chimneys as soot floated toward the roofs of the town churches. There were many new job opportunities for young women yearning for independence-"at least forty thousand spindles in operation" throughout the region, Catharine wrote-each filled with women praying for respite from servitude in the cities, or hoping to escape the trying life as a farmer's wife.

Catharine seemed quite fond of Fall River and its history, both recent and more ancient. She wrote: "It requires no great effort of imagination to go back a few years and imagine the Indian with his light canoe sailing about in these waters, or dodging about among the rocks and trees. The neighborhood of Fall River has been the scene of frequent skirmishes among the Picknets, the tribe of King Philip, and the Pequods and Narragansetts. Uncas too, with the last of the Mohicans and the best, has set his princely foot upon its strand."

But while Sarah Cornell's death was the focus of the first narrative book of macabre murder in America, it would not be the last in Fall River. In the years after Catharine first told Sarah's story, other dark events occurred in the surrounding streets. That's where I'll contribute to Catharine's observations of Fall River's history by adding more context with darker details.

After the village was renamed in 1856, its population grew, as did its crime rate. It has been referred to in the modern press as a “cursed city,” though I’m not certain that reputation was earned. Less than a twenty-minute walk from John Durfee’s farm (now Kennedy Park) is a section of the city measuring about two blocks, where a series of freak, media-grabbing tragedies occurred spanning a century. These were not simple domestic disputes or botched bank robberies. They were deaths that seemed so out of the norm that they were triggered by a cloister of demons hiding in the shadows (or so some local tours claim).

The most notorious tragedy in Fall River happened in 1892, when Lizzie Borden was tried for murdering her father and stepmother with a hatchet in their multilevel Fall River home. The case grabbed headlines across the nation for its brutality, and also its aftermath-Borden was eventually acquitted by a jury, an all-male panel unconvinced that a respectable middle-class woman could butcher her parents. Later investigators weren't so sure about that. The Borden murders still draw countless tourists to the house every year, particularly around Halloween.

But tragedy had long stalked the Borden family. Four decades earlier, Lizzie Borden's great-uncle Lawdwick Borden and his wife, Eliza Darling Borden, lived next door to the Borden house on Second Street in Fall River. Eliza had three children with Lawdwick in quick succession, and afterward she grew increasingly depressed, apparently suffering from postpartum depression that went untreated. In 1848, after months of despair, the thirty-six-year-old Eliza drowned two of her three children, Holder and Eliza Ann, in the home's basement cistern, before slitting her own throat with one of her husband's straight razors.

There were five horrific, violent deaths at two locations just feet from each other, all involving the Borden family. But preceding those fatalities, the block was touched by another doomed event, a seemingly innocent accident directly across the street from both homes. On July 2, 1843, a deadly fire ripped through that section of Fall River, nearly destroying a large portion of the city; historians believe it began with two boys who were exploring the back of a three-story warehouse near the corner of Main and Borden Streets. The boys discovered a small cannon that was going to be used for Independence Day festivities in two days, and, being curious, they fired it. The blast ignited a scattering of wood shavings on the ground, left behind by workers in the warehouse. The shavings flamed and the fire spread quickly, thanks to the dry summer winds caused by months of 90-degree temperatures. Within five minutes, the fire raged. Fall River's fire bell clanged as terrified residents evacuated onto the streets, including those at the Borden home across the street. A sheet of fire pushed onlookers backward.

"Showers of sparks and cinders, carried by the heavy wind, kindled many buildings before they were reached by the body of the fire," detailed the author of The History of Fall River. "The whole space between Main, Franklin, Rock and Borden streets was one vast sheet of fire, entirely beyond the control of man."

Excerpted from THE SINNERS ALL BOW by Kate Winkler Dawson. Copyright © 2025 by Kate Winkler Dawson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Sinners All Bow: Two Authors, One Murder, and the Real Hester Prynne

- Genres: History, Nonfiction, True Crime

- hardcover: 320 pages

- Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

- ISBN-10: 0593713613

- ISBN-13: 9780593713617