Excerpt

Excerpt

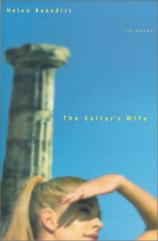

The Sailor's Wife

![]() Chapter One

Chapter One

Ifestia sat in the middle of the North Aegean, isolated like a raft in a bay. The western half of the island, where Joyce lived, was the unlucky half: dry and treeless, rocky, its earth the color of sand, its scrub silvery and timid against the solid blue of the sky. Few tourists visited Ifestia, for it lacked the drama of the islands Lesbos and Thasos nearby, and it was constantly overrun by bored, restive soldiers.

The island was also poor. The peasants of Ifestia had to struggle like peasants everywhere, but on the western side they were helped by neither fertile soil nor natural ponds. Their goats were more suited to the land than they. Joyce's mother-in-law had worked so hard all her life that she'd never had the leisure to learn to read. Both she and her husband told time by the sun. They looked like shriveled prunes, but their muscles were as dense and knotted as wood.

In 1975, by the time Joyce had spent two years getting used to life on the island, more soldiers than ever came and drove away the few remaining tourists she liked to seek in town for company. They drove away the Germans, who shouted commands and never said thank you; the English, who drank too much and burned themselves a lobster red in the sun; the rare Americans, who gawked at Joyce when she spoke and begged her to find them bargains in the market. And they brought instead playfulness and lust and dark, quick eyes waiting to catch her like nets. They brought young male bodies, gleaming hair, laughter, carelessness — everything she had relinquished.

Joyce stood in the marketplace one summer morning, selling the week's produce from her in-law's farm. She had grown thinner during her time in Greece, her once soft limbs now sinewy and hard. Her family in Florida would barely recognize her. Her skin, unprotected by lotions, had deepened to a honey brown. Her hair, long since grown out of its bleach, was tied back in a dark golden knot. Her green eyes looked paler than they used to against her new complexion; sage in the sunlight, olive in the shadows, giving her narrow face a look of feline secretiveness. Her lips, unadorned by cosmetics, were thin and delicate. But her legs glinted with long, blond hairs, and her hands and feet were scraped and cracked and seamed with dirt. Her dress — her mother-in-law never let her wear trousers — was a shapeless pink, faded and stained. On her left hand, her wedding ring had grown dull with neglect.

She was selling eggs and the oil and seeds from her in-law's precious sesame plants. She also sold spinach, dark and crisp. Basil, lentils, and beetroot that ran red as a wound. Beans, pungent marjoram, globes of perky garlic. Little red potatoes, sweet as plums. She sold from a rickety stall in the small market square, and she had learned to drive a hard bargain.

"For you, Kyria Fakinou, I will throw in an extra egg, but only if you buy my garlic here. It is the sweetest in the market, watered by my mother-in-law's own sweat and tears. Yes, and my eggs are three centimeters bigger than any others — you bring a measuring tape and see!"

The townspeople liked to buy from Joyce. They found her American malapropisms amusing as she wrangled with them in Greek. They liked to gaze at her hair, which she often forgot to hide under a scarf, as a proper young woman should. The old teased her about being a rich Amerikeedah who had come to live like a peasant. The young matched their wits against hers to see if they could outdo this upstart Yank. Joyce relished all this. It made her laugh with triumph, with pride. With affection.

She sold from dawn until almost noon. Then, when the market was emptied, the sun high and strong, and her voice raw from calling out her wares, she strapped the wicker baskets onto her donkey and headed home for the remainder of the day's chores.

"Hey, little mama, you go home already?"

It was one of the soldiers. They taunted her every day in pidgin English or saucy Greek. She turned her back on him and steered the donkey out of the market square, frowning. Her only protections were Greek curses, her married status, and spitting. Yet sometimes she longed to kick the donkey away, undo her hair, and dance into the soldiers' arms. Nikos, her husband, had been away this time for seven months, the last time for almost five. He had deflowered her, given her a taste for it, kissed her, and fled. Left her gasping like a fish on a bank. In between he wrote her long, steamy letters in broken English that made her toss in the night, her fingers between her legs, hoping her in-laws on the other side of the wall could not hear her panting.

"Come with me, baby. I lick you all over."

The men hissed in her ear.

The vegetables sold badly that morning — there was too much competition at that time of year — and as Joyce walked the donkey home, she worried about her in-laws' reaction. They lived hand to mouth, every bad market day a strain, every quirk of weather a potential tragedy. She had learned this on only her fifth night in the house. Lying wet and sweating in Nikos's arms, her thighs streaked with semen, she had been awoken by the shouts of his mother. A windstorm had risen from the sea and swept all the sesame seed capsules off the plants just a day before the harvest. Her father-in-law lit a kerosene lamp and plunged out into the storm, his wife shouting at Nikos and Joyce to join him. They ran from plant to plant in the darkness and rain, scrabbling at the ground for the capsules, praying they had not burst open and scattered their precious contents to the wind. But it was useless. The most valuable crop of the year, destroyed in an hour.

That had been before Joyce knew Greek, when she and Nikos could barely speak to one another, only touch.

The first time Nikos had left was only six days after he had brought her home. "I back soon," he'd promised, then disappeared for five months. He was a merchant marine, working for Greece's great glory, its shipping magnates. The ships went tramping, as the Greeks called it, all over the world. Instead of following set routes like other shipping companies, they took one-time trips anywhere that paid. "I go only Spain," Nikos had assured Joyce. "I come home and bring back much money." His mother, Dimitra, had laughed approvingly and rubbed her fingers together. No one had told Joyce that was how it would always be.

For weeks after Nikos had left that first time, Joyce lay in her bed each night, aching with exhaustion and loneliness. After she'd overcome her fear of bats, she would leave her wooden shutters open so that she could see the night sky through her window; and the boundaries of her life, of the room around her, the bed beneath her would seem no more solid than the ceiling of the Milky Way. Where am I? she would find herself wondering. How did I get here? Who knows me? She had felt herself floating loose, drifting on the edge of a void, tethered only by the thin, tenuous strand of Nikos's love.

Joyce led the donkey, a tired old male called Phoebus, through the dusty fields to her in-laws' house. They lived above Kastron, the main port on the western coast, up a hill of treeless volcanic rock. As she left behind the cluster of whitewashed stone houses, their walls blinding in the sun, their umber roofs dulled in its glare, the heat seemed only to increase. It breathed down on her, cooking the pale yellow dust beneath her feet as it cooked her hair, her flesh, her thoughts. Around her, the grass was scrubby but fragrant with herbs: oregano, oleander, sage, mint, thyme. The only sounds were the clop of the donkey's feet, the rasping of cicadas, and the creak and rustle of the baskets on Phoebus's back. His hooves scuffed up the dry earth, making Joyce cough.

Joyce was dizzy from lack of food. It was August and the people of the village were fasting for the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. They could eat nothing that symbolized Jesus Christ, so could have no product from the olive, upon which they usually depended. No fish, either, no lamb, no sheep's cheese, no wine. For nearly two weeks she and her in-laws had lived on watermelon, potatoes, and bean soup; not enough, for Joyce at least, to sustain her constant labor. At the end of the fast, however, Petros, her father-in-law, had promised, they would catch a boat to the neighboring island of Lesbos, hitchhike to the mountaintop, and feast for three days.

Joyce tethered Phoebus to his post and stumbled through the back door of the squat stone house, scattering the chickens and hideous guinea fowl that ran at her feet. Inside the white-plastered walls, the shade soothed her like satin. She threw herself on the Turkish pillows piled in a corner. As her sweat dried she felt the dust form a gritty seal over her skin.

"Any good today, little one?" Dimitra said, entering the house. She, too, in her blue sack of a dress and bare feet, looked layered in dust. She was carrying a huge earthenware jug from the well. They had no running water.

"No good, Mama, I'm sorry," Joyce replied. She handed over the meager purse of drachmas. "Alexis was there with his crops — he had three times as much as ours. He cut the prices. And people aren't buying much because of the fast."

Dimitra frowned but said nothing. She heaved the jug up on the rough wooden shelf that served as a kitchen counter. Although Dimitra was sixty-four, the sun and work had made her look eighty. The skin on her heavy, square face was as cracked as dry earth, caving in at the mouth, where she had lost several of her bottom teeth. Her once wide almond eyes were dim and hooded. Her hair was now a steel gray, braided and circled about her head like a crown. But her back was upright, her heavy bosom proud. She was as strong as any man.

"And the eggs?"

"The eggs I sold. And the potatoes. The money is there. Can I wash, Mama? I feel dizzy with the heat."

"Go wash. No soap on your feet!"

Dimitra said this to her every day, barking it in her gruff, rasping voice. Soap on the feet makes a young girl infertile, she told Joyce over and over. Joyce laughed to herself as she splashed water on her legs at the outside pump. How am I going to get pregnant with Nikos across the sea? What does Dimitra expect, immaculate conception?

In the supermarket, Nikos had followed her as she filled her shopping cart. He had mimed questions to her, compliments. "Amerikeedah pretty," he'd kept saying, the only phrase she had understood. But his teasing eyes, his strong, tanned limbs — she understood those. He paid for his oatmeal and followed her outside to her car, where he stood clutching his shopping bag and looking bewildered.

"Are you lost?" she said hopefully.

He frowned. "I walk here. Far." He lifted his shoulders in a shrug.

She invited him home "My mama and papa will help you," she said, figuring those were universal words.

"Mama good, yes?" he replied and went with her without protest, as if he had planned it all along.

Her parents welcomed him with surprised curiosity, while she explained that he seemed to have wandered away from his shipmates. They were used to seeing sailors in Miami, although they had never had one to the house before — the sailors usually stayed around the bars and clubs in South Beach. Nevertheless, they took pity on him and invited him to a barbecue out in the yard. Her father flipped patties, her mother served drinks. Joyce's two elder brothers, meaty and blond, snickered uneasily at Nikos and refused to take their eyes off the living room television.

"Where did you say you're from?" Joyce's mother asked eventually, her smile oozing like her hamburger.

"Ehlenekoss." He patted his chest. "Amerikeedah," and he pointed to her.

"What in God's name is the man saying?" Joyce's mother murmured.

"He's Greek, Mom, I told you. I think his ship came in yesterday."

"Ah yes, Greek." The mother looked at him calculatingly. "Moussaka!" she pronounced with triumph.

Nikos nodded and flashed his crooked white teeth.

After the meal, Joyce offered to drive him back to the ship. As soon as they climbed out of her car, he took her hand and kissed each finger as solemnly as if he were at prayer. "You are so beautiful," he said, a phrase he knew from pop songs. He said it to each finger, looking at her seriously with his amber eyes.

Joyce's heart squeezed until it hurt. He was so alive compared to everyone she knew, so exotic.

She moved to him, tilting up her face, opening her eyes as wide as she could. "You are beautiful, too."

Excerpted From The Sailor's Wife, by Helen Benedict. © October 1, 2000 , Zoland Books used by permission.

The Sailor's Wife

- Genres: Fiction

- hardcover: 224 pages

- Publisher: Zoland Books

- ISBN-10: 1581950241

- ISBN-13: 9781581950243