Excerpt

Excerpt

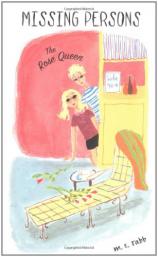

The Rose Queen (Case #1)

Chapter One

Three days after our father died, my sister woke me up in the middle of the night and told me to start packing.

I squinted at her. "Are you sleepwalking again?" She'd gone through a sleepwalking phase a couple of years ago when she was fifteen, bursting into my room and yelling ridiculous, incomprehensible things like, The tissues are coming! and, Stop the elves!

"Hurry up. We don't have a lot of time," she said, ignoring my question. She had brought one of our parents' old black suitcases into my room; she pulled open my dresser drawers, then began to throw piles of my underwear, winter sweaters, and flannel pajamas into the open suitcase.

I gaped at her. "What are you doing?"

"We have to go," she said. "We have to get out of here."

I pulled off the covers and put on my shark slippers. My first thought was that we were going on some kind of vacation. It wasn't a bad idea—we both needed to get away. Being in the house by ourselves was unbearable. The brick house in Queens, which we'd lived in our whole lives, seemed to echo and rattle with the fact that both our parents were gone now. Our mom had died six years before, and you would think that after that much time you'd get used to it, but I hadn't. Everything in the house made me miss my mom—her navy blue pea coat hanging in my closet, her photos on my shelf, her silver locket in my jewelry box. And now my stomach clenched every time I glanced at my father's wool cap dangling from a hook in the hall, the piles of mail addressed to him that still arrived relentlessly, and the grocery list in his familiar handwriting taped to the fridge, alongside his medication chart.

I still kept expecting him to shuffle down the hall in his sheepskin slippers, asking me, "You're not getting on the subway in a skirt that short, I hope?"

"Yeah, I am," I'd say. My skirts were never that short.

I should've prepared myself for the possibility of him dying. He'd struggled with heart disease ever since our mom died; he was on so many medications that he had to make checklists to remember to take them. His doctors had said that he had a high chance of having a heart attack, but the risk never seemed real. Then three days ago, he just didn't come down for breakfast in the morning. We thought he was sleeping late, but when Sam went up to wake him, she screamed my name, and as soon as she did, I felt dizzy and numb. Which was how I'd felt ever since.

Sam stared at the suitcase on my floor, looking like she was about to hyperventilate. I finally just started throwing things in it to appease her. All we'd done for the past three days was mope around in a comalike state. Earlier that day, after the funeral, we'd sat shiva, the Jewish ritual to mourn a death. We covered the mirrors, wore the traditional torn black ribbons pinned to our clothes, and stayed at home to greet our neighbors and friends and thank them for the casseroles and brownies they brought, which I had no appetite for. Nothing made me feel better. I couldn't believe that just that morning, we'd watched our father's body being lowered into the twin grave beside our mother's. It had been raining, and my sister and I had huddled beneath a Snoopy umbrella. You will always be with us, our mom's headstone read. Was that even true? I'd cried so much in the past three days that I couldn't even wear my contact lenses; my eyes were too swollen. I had to wear the monstrous thick plastic-rimmed purple glasses that I hadn't worn since sixth grade. The rabbi droned on in Hebrew—"El Maleh Rachamim . . ."—and I looked at my sister and thought, We have nobody now. It's just us.

And there we were, just us, in my bedroom with a half-packed suitcase on the floor between us. Sam sat back on her heels and said, "I've figured out how we can run away."

"What are you talking about?"

"Leaving. For real."

"You're crazy," I said. "Where are we gonna go? We can't just leave. We're still sitting shiva. And I—I'm baby-sitting tomorrow. And we don't have any money—"

"We have money. I have it all planned out. We can't wait any longer—we have to go now."

She was shoving more and more of my stuff into the suitcase, as much as she could fit.

"If we don't leave now," she said, "when Enid inherits everything, she's going to ship you off to that boarding school in God knows where, and God knows how long will it be until we see each other again. The most important thing, no matter what, is that we stay together. That's what I promised Daddy—that we'd stay together. Enid made the same promise to him, but we know she's not going to keep it."

We'd joked about running away ever since our dad had married Enid—a tall, wiry woman who called us "the young ladies" in the same tone she used for "the rodents in the subway." Enid spent most nights in her apartment in Manhattan, which she'd kept during her whole two-year marriage to my dad; she didn't like trekking to Queens all the time since she said cabs were too expensive, and she hated the subway. And my dad kept her up at night with his snoring, she added. Whenever she did make it out to our house, she found things wrong with everything we did—the dishes weren't clean enough; the house was too dusty and cluttered; I played my music too loud and my clothes were too tight; Sam studied too much, her haircut made her look like a boy, and she needed to lose weight.

Then there was the time, about six months before, when I'd overheard Enid talking on the phone to her mother.

"The Langmoor Academy," Enid had said in her gravelly voice as she took notes. "Sounds perfect for the younger one."

That's how she referred to me—"the younger one."

"What's the Langmoor Academy?" I'd asked her later that night, when we were alone together in the kitchen.

"It's a fine boarding school, in Alberta, Canada," she'd said. "I've been trying to come up with a plan for your future, in case . . ." She lowered her eyes. "With the exchange rate, tuition's practically free." She went on to say that the school focused on rehabilitating unruly youths by packing them off on outdoor adventure trips, like climbing the glaciers of the Yukon. No joke. The school probably charged only a little bit extra to permanently lose one of their pupils in an abandoned ice cave or to toss them into a flaming volcano.

I'd told my father what Enid had said. He'd simply responded, "I know Enid would never do that. There must have been some kind of misunderstanding. She'd do her best by you. She loves you very much." He trusted her. To her credit, he'd been happier since he married her than he'd been in a long time—after my mother's death he spent most nights on the couch, slumped in front of the TV; but once he met Enid, he started to go out to dinner and movies and free concerts again. He slowly began to seem a little bit more like his old self. As grateful for that as I was, I wished my dad could have seen through her. Enid had brought up the Langmoor plan again that afternoon, at the reception. "They have room for you this fall," she'd told me. Children, to Enid, were something to be endured, like the flu, until they could be passed on to someone else.

I'd thought that the talk about running away had been just a joke—though apparently Sam had been taking the idea a little more seriously than I had.

She stared at my Scooby-Doo alarm clock. "We have thirty minutes to get out of here."

"What about NYU?" I asked Sam. Even though she was only seventeen, she had graduated from high school a couple of weeks ago and was supposed to start college in late August, in less than two months. "You've been looking forward to going for so long—"

"I'm postponing it."

"Why? You've been planning on it—"

"I've been planning on this," she said. "I'll go to college—we'll both go to college. But it's important that we can both afford to go to college and not be so far away from each other. That's why we need to get out of here."

"How much money do you have? Five dollars? A hundred? We don't have enough to live off. I have, like, ten dollars." I waved at the tiny purple piggy bank on my dresser, covered with scratch-'n'-sniff stickers.

Sam took a deep breath and looked down at the suitcase. "Actually, we have about three hundred thousand."

My throat dried up. "What?"

"We have three hundred thousand dollars." She seemed kind of surprised, and pleased, to hear the amount stated so plainly out loud.

"You're kidding."

She shook her head. "I figured out a way to transfer Daddy's money into our names. Well—our new names. Felix helped me. That's why—that's where we're going now, to his place, to trade in the car and get some new IDs for ourselves."

Felix was one of Sam's best friends from school; he operated a fake-ID business out of his basement. Sam closed the suitcase and zipped it up, then started dragging it down the stairs.

I couldn't believe this was happening. "You stole Daddy's money?" I asked as she opened the kitchen door.

"Could you keep it down a little?" She made sure no one was eavesdropping outside, then shut the door again. "It's not stealing. That money's rightfully ours—it's Mommy's life insurance and Daddy's life savings. If we stay, everything goes to Enid—everything. She wouldn't let Daddy leave the money in a trust, with her as the fiduciary, no, it was all to her or nothing. See, if it was a trust and she spent the money in a way we didn't see fit, we could sue—and we'd probably win. She didn't want that to happen. So the money's all hers now. Or it's supposed to be."

I blinked at her. "What are you babbling about? Judiciaries?"

"Fiduciary. Help me with this suitcase. It means Enid would be in control of the money, but she'd have to spend it for our benefit. But that's not how it will be now. Now she can blow it all on twenty-calorie Weight Watchers fudgsicles or weight-loss programs for her mother, and there'll be nothing we can do about it."

Enid bordered on the insane, especially when it came to the subjects of children, weight loss, and money. She belonged to an organization that tried to have restaurants instate no-children-allowed policies. She meticulously recorded every penny she spent, and her idea of a nice birthday gift was a crisp five-dollar bill or a regifted box of chocolates that were too fattening for her to eat. Though she was close to six feet tall and weighed about a hundred and ten pounds on a good day, she was perpetually obsessed with her weight. She recorded every calorie she ingested on her Palm Pilot, and often you could hear her murmuring to herself while staring out the window or clearing the table: "One slice bread, sixty; a pickle, five; mustard, two . . ." Once she made my dad drive around to four different stores, looking for her twenty-calorie fudgsicles.

We loaded the suitcase into the car, but I still wasn't convinced that we were actually going to leave. Back in the kitchen I told Sam, "I just think—there must be something we can do. You'll be eighteen in a few months—can't you be my legal guardian or whatever? I can stay with you. Or I can get court permission to be on my own—I saw that on Law & Order." These had been my secret plans whenever I let my mind wander about what would actually happen if our father died, which had only been a few times. I always thought that if I imagined it, then I might somehow make it happen. And he had seemed fine before he died—I knew he had his heart problems, but he looked the same as always. I think a part of me believed he'd live forever. Or at least a long, long time.

"There's no guarantee that I'd be allowed to be your legal guardian or that you'd get that court permission," Sam said.

"Then we can contest the will—"

"You think a judge would really decide against Enid and a legal will in favor of two teenagers?" She shook her head. "No way. And there's the most important thing—we can't be separated. No matter what, we're staying together, and no one can stop us from doing that."

I stared at her. I couldn't even imagine what it would be like if we were apart.

"Listen, Sophie, we can't stay here all night arguing. Just pack up your stuff and we can talk about it more in the car."

Maybe we didn't have any other choice. I started putting my things into shopping bags. A part of me didn't mind the idea of leaving—the house felt like an empty box without our father in it. Abandoned and deserted. We couldn't keep living there, pretending that things hadn't changed. They had changed, and we had to do something, go somewhere, and I had no idea what we should do. At least Sam had a plan.

And maybe we were only going away for a little while. "We're coming back sometime, right?" I asked Sam.

She hesitated. "Yeah. Sometime."

I hoped she was telling the truth.

I loaded my things into more suitcases and shopping bags. "We have to fit it all in the car," Sam said, "so only take what you really need."

I needed everything. I packed my mom's pea coat and my dad's wool cap. I packed all my jewelry and makeup, and my two hair dryers (regular and travel), and all my hair gels and perfume, my straightening iron and my hot rollers. I scooped everything hanging in my closet into a Hefty bag.

I kept going back into the house for more stuff—all my photo albums, the scrapbook I'd made of our mother, and my Martin guitar. My father's cotton T-shirts and his sweaters, which still held his warm, comforting smell, like spices and soap. My magazines. A bunch of my favorite books, though I couldn't bring them all. I made sure to take The Complete Sherlock Holmes-my dad's old hardcover copy that he used to read to Sam and me-and a full set of Anne of Green Gables, which my mom had bought me. I also threw in some other favorites—To Kill a Mockingbird, The Little Prince. I knew there would most likely be bookstores and libraries wherever we were going, but I wanted my copies of these books with the pages I'd folded over and read and loved.

Sam had packed earlier—the car was already loaded with her suitcase, laptop computer, printer, and file folders.

She shook her head as I kept making trips back and forth to our dad's Toyota. It looked like it was about to split open from all my stuff. "Sophie, there will be stores wherever we end up. You don't need to bring everything you own. Someone's going to see us."

"No one's going to see us," I said. The houses on our block were dark. Occasionally someone walked by down the sidewalk, but nobody we knew. "And this is the last of it."

"All right," she said. "Are we ready?"

"Wait." I ran back inside for Ed, my stuffed polar bear—I'd left him on my bed. I also grabbed my Scooby Doo clock, my nail polishes, and my father's beloved framed Brooklyn Bridge poster from the living room wall.

"Nothing else is going to fit in here," Sam said. She was leaning against the car, with her arms folded.

"Okay," I said. "This is it. I've got everything." Though even as I said it, my heart sank at the idea of everything we were leaving behind. Furniture I loved and plants, paintings, our parents' flower-patterned sheets, and a million other things I would miss. I'd lived in that house my whole life. I just couldn't get used to the fact that it was only Sam and me now. It made me feel like a different person, that we had no parents anymore. In movies I'd seen and books I'd read, it had always seemed like orphans were these strong, indomitable people who could overcome and conquer anything—but I just felt so not strong, so not capable at all. I felt like a huge mess. I hurt all over, this horrible ache in the pit of my stomach and in my whole chest, and it didn't seem like it would ever go away.

Sam shoved Ed into a crevice in the trunk and slammed it shut. I stared around our neighborhood. The old attached brick houses and tiny yards. The alleyway behind our house where we used to play hide-and-go-seek and kick ball. The fact that we were leaving, that this might be the last time I ever stood here outside our house in our neighborhood, didn't sink in. Nothing felt real—not the sound of Sam turning on the ignition or of me closing the door, or the sight of our house disappearing as we turned the corner.

Excerpted from Case #1: THE ROSE QUEEN © Copyright 2004 by Margo Rabb. Reprinted with permission by Puffin Books, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. All rights reserved.

The Rose Queen (Case #1)

- paperback: 192 pages

- Publisher: Speak

- ISBN-10: 0142500410

- ISBN-13: 9780142500415