Excerpt

Excerpt

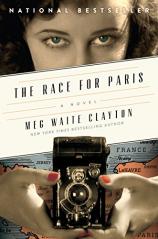

The Race for Paris

A Field Hospital in Normandy

Thursday, June 29, 1944

*

So you want to go to war? . . . You won’t be very comfortable. Things will happen you won’t like. Do you think you can take it?

—Chief of the War Department’s bureau of public relations’ war intelligence division, speaking to AP journalist Ruth Cowan

*

Back in our tent, Marie was in her bedroll under her cot but still awake, just returned from the muddy trench behind the tent. Liv and I climbed under our cots, too, as if that would provide any protection at all. I buried my notes from the operating room underneath me lest they be destroyed, and suggested Liv do the same with her film. We both tucked our clothes into our bedrolls, to keep them dry. And while in the distance German bombers droned and American ack-ack answered, Liv said, “I don’t know anything about scalpels or morphine. All I know is shutter speeds, f-stops, angles of light.”

I said, “Most of the soldiers who make it here from the front, they survive, Liv.” But I, too, was having trouble shaking off the sound of the boy asking for peach ice cream, the inadequacy of what I could do even when I did my best. And the best of my words were no more likely to be published than were the best of Liv’s photos. The filthy, stricken, raw bloodred wounded were too stark a contrast to the fresh-faced American heroes the public imagined. They would never get past the censors, much less newspaper editors focused on sales.

“Charles feels it’s the right thing to do, to stick with photos and stories that will go down well enough with the morning coffee,” Liv said. Her husband was the editor in chief of the New York Daily Press;Liv, who’d gone to work for Charles’s paper after we joined the war, moved to the Associated Press after she became Mrs. Charles Harper. Charles’s paper was in the AP consortium so he could still use her photos, and Liv would never have been accredited as a war photographer if she hadn’t moved to AP.

Marie wondered aloud what her fiancé was doing—a boy to whom she’d gotten engaged just after Pearl Harbor. He’d gone off to enlist, and she’d been heartbroken, and he’d returned without a uniform and she could neither go through with the wedding nor call it off, and she’d fled; she supposed that’s how she’d gotten to France. 4F. It meant only that her fiancé was disqualified from military service for medical reasons, but medical excuses were drummed up easily enough that 4F carried the stink of cowardice as surely as did Liv’s husband remaining in New York.

“Charles was in Warsaw when the Germans invaded,” Liv said. “He and his photographer stayed even after the lines were cut and they couldn’t get stories or photos out.” She pulled her bedroll more tightly to her throat and shifted her head, awkward in her new steel helmet. “Even when the Polish government fled to Nałęczów, Charles stayed to cover the invasion.”

A clock tower in the next town marked three a.m., an echoing bong, bong, bong followed by silence, the absence of drone and ack-ack, which might last or might not.

“I brought a ball gown,” Liv whispered into the blackness, that late hour when it’s always easier to share the things we hold close.

“A gown?” Marie said just as I said, “Here? To France?”—our voices as soft as Liv’s: a secret revealed, a secret received.

Liv had stuffed the silk sheath in with her gear at the last moment, and evening gloves, too—gloves of soft kid leather that went up over her elbows, dyed the red of the dress.

“The gown folds up to be just a tiny little thing,” she said, and I imagined her gloved right hand in her editor in chief husband’s left, the two of them twirling around a ballroom, drinking champagne and laughing as nobody had laughed since the war began while, just blocks away, a child slept in a crib in the room next to theirs.

I said, “Three children, two sons and a daughter—that’s what I want someday.”

“I want five,” Marie said.

“A Renny and a Charles Jr.,” Liv said, “after the war.”

Liv said, “‘If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough’—that’s what Robert Capa says.” Her voice wistful, lacking the force she’d been full of when she’d arrived that morning. “But I’ve been an ocean away. I’m still miles away from the front while Capa and Frank Scherschel and Ralph Morse are already on their way to Paris, making their way with the troops toward the city, to the Eiffel Tower and the Champs-Élysées and liberation, Allied troops marching in to throngs of crowds filling the streets, celebrating what will be the moment of the century. A moment that will make a photojournalist’s career.”

“Make your career,” Marie repeated under her breath, a reprimand. We were all supposed to be doing whatever we were meant to do to win the war. We were to follow orders. We were to set aside our discomfort. We were to do everything for the war effort, and nothing for ourselves.

“Well, for my part,” I said, smoothing over Marie’s censure and tucking away my own, “I figured I’d be an old maid by the time the boys returned home, so I thought I’d best come here to find a beau!” As if I’d skipped the whole routine of accreditation and vaccination, passport and visa and PX card, and gone directly to be measured for my Saks Fifth Avenue uniform—which had been the idea of my publisher’s wife, as had been my move from the typist pool to the books page, from journalist to foreign correspondent. Lord & Taylor had made Catherine Coyne’s uniform to order for the Boston Herald; Savile Row had made Helen Kirkpatrick’s; and when Patricia Lochridge went to the Pacific for Woman’s Home Companion, Saks made hers, and Mrs. Stahlman insisted the Banner’s women readers would accept no less for their own “Intrepid Girl Reporter,” whom she insisted they have. That was the truth of how I got to Europe: my mother washed Mrs. Stahlman’s dishes and mopped her floors, and Mr. Stahlman owned the Nashville Banner, and Mrs. Stahlman—who wanted a lady war correspondent like the big-city papers—could imagine me in a role I’d never imagined for myself. I’d lived my whole life on the wrong side of Nashville and that was my future, and this was my one shot to change that.

None of our reasons for going to war made sense, and yet they all did.

The drone of planes sounded again, faint but present, and Liv and Marie and I started singing together, lying underneath our cots and waiting for morning to come around. We sang softly, barely over whispers, just because it felt good to sing. “The White Cliffs of Dover.” “Always.” “As Time Goes By.” I closed my eyes to block out the shadow of canvas cot above me, the drone and the ack-ack, the sharp corner of my notepad pressing against my back. And I imagined I was a girl again, singing alongside Mama’s high, sweet soprano voice, just the two of us in harmony as we washed Mrs. Stahlman’s Wedgwood china in the big sink in the big kitchen at the Belle Meade mansion, where I used to imagine I might someday live.

The Race for Paris

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Harper Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0062354647

- ISBN-13: 9780062354648