Excerpt

Excerpt

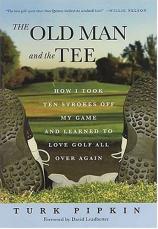

The Old Man and the Tee: How I Took Ten Strokes Off My Game and Learned to Love Golf All Over Again

CHAPTER 16

Semi-Drunk

"I see myself as a monstrous, manned colossus poised high over the golf ball, a spheroid barely discernible fourteen stories down on its tee.

- George Plimpton,

The Bogey Man

Despite a couple of remarkable holes, the main thing I learned at Sand Hills was that I didn't have the shot-making ability needed for a true links course. The obvious solution was for me to play courses that require the widest variety of shots. That meant I absolutely had to go to Scotland --- at least that's what I told Christy, who'd begun responding to my ever-increasing travel plans with a rueful shrug.

On the way to Scotland, I stopped in New York to see some pals from my acting stint as Janice's narcoleptic boyfriend on The Sopranos. ("Have you heard the good news?") Despite the fact that Tony Soprano tees it up occasionally on screen, James Gandolfini has never played the game. The show's number-one linkster is Steven Van Zandt, who plays club owner Silvio Dante and is also, of course, the lead guitar player in Springsteen's E Street Band. Over dinner at the set one evening, Steven told me about taking up the game a few years earlier in order to spend more time with his father. With his dad having since passed away from Alzheimer's, the father-and-son rounds they shared are no doubt more special to Steven than ever.

Yet another great thing about the game of golf is that, even though Steven and I hardly know each other, we share an important bond, and it has nothing to do with The Sopranos. What we share is the good fortune to love the same game our fathers loved. Whether it be golf, baseball, or ice fishing, everyone should be so lucky.

Wishing more than ever that I could tell Pip about my lessons and travels, I began at this point to write in earnest about my golf odyssey, and had the opportunity in New York to seek advice from a master of the game --- the writing game, that is.

In a small bar on the Upper East Side, I joined my onetime tournament partner, author and actor George Plimpton, who had turned much of his life into art in his books about playing quarterback for the Detroit Lions, flying on a trapeze for the Clyde Beatty Circus, and playing percussion with the New York Philharmonic, where he inadvertently banged the bells so loudly that Leonard Bernstein stopped the concert to applaud him. Another of Plimpton's books, The Bogey Man, chronicled his woeful attempt to compete in the PGA.

Trying to find some method in the madness of my ten-stroke quest, and hoping to write a book that might cover some of my mounting debts, I asked Plimpton if he had any advice for me on the subject of participatory journalism.

"Don't be afraid to come across like a dumb ass," he told me in his genteel Harvard accent. "I lost thirty yards in five plays for the Lions and was certain I'd ruined my book. It wasn't till much later that I discovered my ineptness made the pros seem all that more powerful and skilled. My failure turned out to be a success."

"But I'm essentially competing against myself," I told him.

"Well," he said thoughtfully, "in that case, you could be in trouble."

I'd met Plimpton a couple of years earlier when Bud Shrake suggested that the two of us play as a team in the Dan Jenkins Goat Hills Partnership tourney in Fort Worth, a raucous outing affectionately referred to as the Meatloaf Sandwich Open.

At the opening-day practice round, my partner mentioned that it'd been a while since he played a full round.

"How long?" I asked.

"Years."

Seeing the look of panic on my face, George reassured me that he'd recently undergone a custom club-fitting at Callaway Golf where he'd also taken a couple of lessons and even played nine holes.

"Nine holes," I repeated.

"I didn't play very well, though," he added. "I was picturing a midget standing just in front of my tee, then trying to hit the midget in the ass with my driver."

"A midget?" I asked.

"A little guy who's pissed me off."

"So you hit him in the ass with your club?"

"Don't knock it till you try it," George advised. Then he teed up a ball and smacked it down the middle of the first fairway.

"Did you get him?" I asked.

"Right in the ass," George said, flashing me a smile.

We were halfway around the course when Plimpton related what he thought might be more of a problem than an extended absence from the game.

"Am I going to need any money?" he asked. "I've only got fifteen dollars and I didn't bring a credit card."

I looked at him dumbfounded for a few moments and then realized that, hell no, he didn't need any money. He was George Plimpton. As if to prove that point, after a fine Mexican food dinner and many margaritas at Joe T. Garcia's restaurant that evening, George asked me to take him to Billy Bob's, the world's largest honky-tonk.

There was a line at the door and a cover charge, but George just walked by everyone and we sailed inside, After a tour of the indoor bull-riding arena and other outsized oddities, we sat in front of a large bartender who looked at George and said, "Hey! You're that guy from Good Will Hunting! Wait! Wait! Don't tell me your name!"

"Buy us each a drink and I'll give you a free guess," George told the bartender without missing a beat.

"Okay," the bartender said. "You're Buck Henry, right?"

George shook his head, we drank our whiskeys, then the bartender poured and guessed wrong again. It was true; George really didn't need any money.

You don't meet many Harvard men who've teed it up on tour with Arnie or lined up in a scrimmage opposite Alex Karras, so for the next hour, I listened to one incredible story after another while the mammoth bartender returned every few minutes for another wrong guess and another round of drinks.

Though Plimpton seemed to think the world of Arnold Palmer, he was most passionate when speaking of Ernest Hemingway, who had slugged George to the ground in an impromptu bare-fisted boxing match in Hemingway's writing room.

"Looking up at Papa," George told me, "I realized we were going to continue to spar and he was going to pound me senseless. So I jumped to my feet, ran behind him, and said, 'That was incredible. Show me how you did it.' So instead of getting killed, I got a boxing lesson."

Still in Cuba, a couple of days later, George arranged a meeting between two of the greatest men of American letters, Ernest Hemingway and Tennessee Williams.

"Papa and I sat at the bar at La Floridita waiting for Tennessee," Plimpton told me as the man-mountain bartender guessed wrong again. "An hour late, Tennessee came in wearing an all-white sailor's outfit, complete with the hat and gold piping. I introduced the two, then Papa turned around, looked Tennessee over from head to toe, and said just three words: 'Not even close."'

With that, Hemingway turned back to the bar and Tennessee melted away in embarrassment.

When we finally stood up to stagger back to the hotel room, the bartender stopped George and said, "Wait! You have to tell me your name." In his most graceful, dulcet tone, the Bogey Man leaned forward and said, "George Plimpton."

A blank came over the bartender's face as he tried to process this information. We were almost to the door and picking up speed when we heard the bartender call out loudly, "Who the hell is George Plimpton?"

Over seventy years old at the time --- and with twin two-year-olds at home --- all the margaritas and whiskeys might have been a bit much even for George. The next morning, he showed up at the golf course with one eye about three inches lower on his face than the other, though that may have been the result of my vision, for I wasn't in much better shape.

Played on Z Boaz golf course --- named one of "America's Worst Twenty Courses" --- the Jenkins tournament is a celebration of Jenkins's 1965 Sports Illustrated story, "The Glory Game at Goat Hills ' " which told the hilarious tale of Dan's well-wasted youth on a hardscrabble course in South Fort Worth. Populating his story with characters like Cecil the Parachute (who swung so hard he fell down), Weldon the Oath (a swearing postman), Grease Repellent (a mechanic), and Foot the Free ("short for Big Foot the Freeloader"), Jenkins was only proving the old adage that truth is funnier than fiction. May the writer with the best memories win.

Through the decades, it's amazing how little Fort Worth has changed. Many of these characters still play golf with Jenkins and the golf course at Z Boaz is no less colorful than the long-since bulldozed Goat Hills track. The fourth at Z Boaz plays past a topless bar (in case you've forgotten what breasts look like) and the seventeenth overlooks a check-cashing liquor store (in case you've lost your own shirt). When I played in the tournament the previous year, a guy in the group in front of us found an elderly man's body floating facedown in a ditch on the course.

The only bodies Plimpton and I were in danger of stumbling over were each other's. After having a sleeve of new Titleists stolen out of our cart while we were warming up on the putting green, George and I played like old men who'd been drinking as if they were young men, and that was good enough for us.

Reminiscing about all this in the bar in New York, George told me he hadn't teed it up again since our outing in Fort Worth, and I asked him if he wanted to return to Texas the following fall and reteam for another shot at Goat Hills glory.

"I'd love that," George told me, though I think we both suspected that his golf days were behind him. Seventy-five years old, with the Paris Review to edit and his memoirs still to write, the last hole of golf he'd ever play would turn out to be number eighteen that day at Z Boaz.

In the usual assortment of crazy Dan Jenkins rules, on the final hole teams were allowed to buy a four-hundred-yard drive. Digging into his wallet for the first time all weekend, George pulled out ten of the fifteen dollars he'd arrived with and purchased the best golf shot of his life. Dropping a ball on the designated spot four hundred yards down the closing par five, George knocked a ball onto the green, then made the putt for an eagle.

And so, thirty years after The Bogey Man, Plimpton finally beat the game.

Without a clue that George would not live another year, in a bar in New York, I raised my glass to him.

"To the Eagle Man," I toasted.

It's wasn't easy to trump Plimpton in the word game, but I could see he liked that one.

"Any advice?" I asked him as we stood to go.

"Play golf," he told me, "then write about it."

There was no bill from the bartender. I was with George Plimpton, and life was good.

Excerpted from THE OLD MAN AND THE TEE © Copyright 2004 by Turk Pipkin. Reprinted with permission by St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved.

The Old Man and the Tee: How I Took Ten Strokes Off My Game and Learned to Love Golf All Over Again

- Genres: Nonfiction, Sports

- hardcover: 288 pages

- Publisher: St. Martin's Press

- ISBN-10: 0312320841

- ISBN-13: 9780312320843