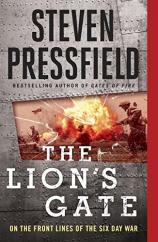

The Lion's Gate: On the Front Lines of the Six Day War

Review

The Lion's Gate: On the Front Lines of the Six Day War

It is easy to see why Steven Pressfield was drawn to the story of the Israeli victory over the combined armies of the Arab countries in the Six-Day War of 1967. Pressfield is best known for GATES OF FIRE, the classic exposition of the Spartan warriors at the gates of Thermopylae, but he is also the author of THE WAR OF ART, in which he develops and shares his theory of Resistance.

Pressfield’s basic concept is that there exists, out there in the ether, an invisible and powerful counterforce called Resistance, which pounces on the artist at the moment of artistic creation and does everything it can to stop the work of art from being produced. Resistance, Pressfield tells us, lies and cheats and fools us into believing that other things are more important than the creation of art. Resistance tells us --- it tells you, it tells me --- that we’re not good enough to create art, that we can’t finish what we start, that no one will care what we do, and those who do care will criticize us and try to tear us down. Resistance, right at this very moment, is telling me that watching a “Kitchen Nightmares” rerun is more important than finishing this review.

"It certainly reads like oral history, and Pressfield undoubtedly has done his homework in interviewing the surviving heroes and presenting their stories."

The job of the artist is about defeating Resistance, overcoming Resistance, leaving Resistance and all its works smoldering in a heap of flaming wreckage. That’s the essence of the Pressfield philosophy, and if it goes a bit too far at times (Pressfield identifies the spouse and children of the writer as potential agents of Resistance, which is more than a bit unfair), it’s a philosophy that’s directed towards the outcome of the production of works of art. Pressfield advocates for hard work, dedication and constant effort, not because it’s a good idea or the right thing to do, but because, if you want to create awesome and lasting works of art, there is no alternative.

For the men of the Israeli air force in the mid-’60s, Resistance was not some amorphous force keeping them from writing book reviews. Resistance appeared in the form of 400 Soviet-built fighters sitting on the runways of Egyptian air force bases. These fighters, if deployed in competent hands, could achieve air superiority over the battlefield, knocking the Israeli jets out of the sky and allowing the numerically superior Arab forces to run roughshod over the Israeli Defense Forces on the ground. An Arab victory would not only mean the defeat of the army and air force but also the destruction of the infant nation of Israel and the decimation of her people. Resistance, in the form of the Egyptian Air Force, must be overcome, because there was no alternative (or, as Pressfield explains, en brera in Hebrew).

Pressfield takes a great deal of apparent joy in explicating the nuances of the plan. The Israeli fighters had to be armed with bombs, which needed to be launched at a certain angle to blast giant holes in the Egyptian runways. Once the bombs were dropped, the fighters would then have to make a 270-degree turn and three separate strafing passes over the parked Egyptian airplanes to ensure their total destruction. This sort of attack had to happen under the Egyptian radar screen and through clouds of anti-aircraft fire. And the attacks had to occur at each Egyptian facility, all at the same time. It was the sort of mission that would have made your average fictional hero throw up his hands in frustration and leave the country for some other country that was not about to be attacked anytime soon.

THE LION’S GATE is about that mission, the Israeli raid on the emplaced Egyptian fortifications in the Sinai peninsula, the liberation of the Old City of Jerusalem, and the capture of the Golan Heights from Syria. It is the story of a shattering victory against impossible odds, fashioned by doughty warriors.

The book’s structure is that of oral history. It is marketed as a “hybrid history,” and as the publisher has not been incredibly clear as to what that means, I will not try to amplify its meaning here. It certainly reads like oral history, and Pressfield undoubtedly has done his homework in interviewing the surviving heroes and presenting their stories. There is obviously a degree of careful editing, a fair amount of cutting and splicing, and the extended monologues from the long-dead Israeli general Moshe Dayan came from somewhere other than a contemporary interview. I am not sure how much Pressfield contributed to the story as a novel, but there’s certainly nothing intrusive about his methods, whatever they may be.

The story of THE LION’S GATE ends with Israeli victory in 1967. It makes no mention of the long-term consequences of the continued occupation of the West Bank, and only throws in the name Yasser Arafat towards the end of the tale. It is a story of martial victory against formidable odds, and not about the political aftermath. It is a rousing book and an important one, but its focus is not essentially on the long history of the Arab-Israeli conflict. It is the story of the fight against Resistance, transposed into a different setting.

Reviewed by Curtis Edmonds on May 16, 2014

The Lion's Gate: On the Front Lines of the Six Day War

- Publication Date: May 26, 2015

- Genres: History, Nonfiction

- Paperback: 448 pages

- Publisher: Sentinel

- ISBN-10: 1595231196

- ISBN-13: 9781595231192