Excerpt

Excerpt

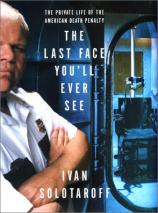

The Last Face You'll Ever See: The Private Life of the American Death Penalty

Chapter One

The Death Belt: Florida to Texas

There were 358 executions between 1976 and 1996, the first twenty years after the death penalty returned to America. Sixty percent were carried out within a two-hour drive of Interstate 10, the southernmost of the coast-to-coast highways. The five eastern states of I-10 are called the Death Belt because of the disproportionate number of executions carried out in their prison farms: in "Old Sparky," Florida's three-legged brown electric chair, which sits in a small, bright room in the state prison at Starke; in "Yellow Mama," the chubby yellow electric chair at Holman State Prison in Atmore, Alabama; in "Black Death," the metal chair in Parchman State Penitentiary's silver gas chamber; in Louisiana's lime-green death house, five miles deep into the woods of Angola, an hour north of Baton Rouge; on the lethal-injection gurney in the midnight-blue death chamber of the "Walls Unit," the massive brick prison that occupies much of downtown Huntsville, Texas. Run a finger down a list of the condemned and notice the three-part names: John Louis Evans III, Jimmy Lee Gray, Robert Wayne Williams, James Dupree Henry, Alpha Otis Stevens, Robert Lee Willie, Edward Earl Johnson, Connie Ray Evans, Arthur Lee Jones, Andrew Lee Jones. That's when you know you're in the Death Belt.

A large, unpainted wood-frame house in Headland, Alabama, fifty miles from I-10, is a de rigueur first stop on any trip through the Death Belt. The ancestral home of Watt Espy, America's foremost historian of executions, it also serves as the offices of his Capital Punishment Research Project. An unfunded, unaffiliated, one-man attempt to collect every available fact about the American death penalty, it is a project to which he has devoted most of his adult life.

Espy, who greets me at the door, is a tall, thin man in black frame glasses, a polo shirt, khaki pants, and tennis shoes with prim anklet socks. He smiles a lot when he speaks, heavy, preoccupied smiles filled with a mournful irony. "These are the condemned," he says, pointing to the head shots, mug shots, wire photos, and book and magazine clippings, all individually framed, that fill the walls. Many hang at derelict angles, others have a crack in the frame glass, and a few show the yellow discoloration that comes with prints taken too soon from the hypo bath, but there's no mistaking the passion with which they were assembled.

Espy tells me their stories, one at a time: a man who willed himself into a coma and had to be carried to the chair; another who strolled in blithely, saying, "I'd ruther be fishin'"; one who came in with a cigar and a pink flower in his buttonhole; a man who had printed the prison tattoo H-A-R-D L-U-C-K on his knuckles; another who handed the electrocutioner a check for his $150 fee, signed "The Devil"; one who asked for bicarbonate of soda before entering the gas chamber; one who said the soup of his last meal was too hot; one who complained from the electric chair, "I sick. I eat too much." Ones who read verse: "Hang me high/And stretch me wide/So the world can see/How free I died," or quoted rap: "You can be a king/or a street-sweeper./But everyone gotta dance/with the Grim Reaper." Those who told their executioners, "Step on the gas"; or "I came here to die, not to talk"; "I am Jesus Christ"; "Hurry it up, you Hoosier bastard"; a woman who warned, "My blood will burn holes in their bodies."

A thin strip of wall in Espy's office bears the house's only images of the living. Six are of his family, including three of an older brother who runs the local savings bank. The other is a head shot of Mario Cuomo, who vetoed every capital punishment statute drafted by the New York State Legislature in his twelve years as governor. "As you might guess," Espy boasts, "I'm a bit of an abolitionist myself." He's also proud to be a recovering alcoholic. "I stayed drunk for the only execution that I will ever attend. It made me physically ill. I vomited."

"Which was that?"

"That would be the botched electrocution of John Louis Evans the Third, State of Alabama, April twenty-second, nineteen eighty-three."

The office, once the living room, has a cranky old copier, a low-end computer, a magnificent library of books on the death penalty, a few dozen photos of the condemned, and a row of file cabinets from the Dewey decimal era, which Espy uses to store execution quotes, names, and factoids on four- by five-inch index cards. The large room is otherwise given entirely to shelves stacked with looseleaf binders formerly used by traveling salesmen. The binders, which Espy buys for a dime apiece in close-out sales, are mystifying at first, as they have their original logos on the spines and covers -- everything from Coca-Cola to local hardware companies. Inside each, Espy tells me, are the details of an era's executions, arranged alphabetically state by state. "That's Indiana behind you" -- he points to a half dozen binders -- "then over into Idaho, Kansas on the far side, down into Louisiana, Mississippi, up through Nevada, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and down again into Texas, which is taking up its share of my attention these days."

I tell Espy I'm headed to Huntsville to see a condemned man, Noble Mays, with whom I'd exchanged letters, then to Louisiana to attend the lethal injection of a man named Antonio James. Espy asks how I feel about corresponding with a condemned man.

"It's a little creepy," I admit.

"I've learned to avoid all contact, though they write me often." Espy seems to have mixed feelings about my...

Excerpted from THE LAST FACE YOU'LL EVER SEE © Copyright 2001 by Ivan Solotaroff. Reprinted with permission by HarperCollins. All rights reserved.

The Last Face You'll Ever See: The Private Life of the American Death Penalty

- Genres: Nonfiction

- hardcover: 256 pages

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- ISBN-10: 006017448X

- ISBN-13: 9780060174484