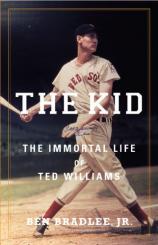

The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams

Review

The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams

At some point, I would guess any thoughtful person thinks about how he or she would like to be remembered. Ted Williams, the legendary outfielder for the Boston Red Sox from 1939-60, never made any secret of it: he wanted to be known as the best hitter who ever played the game (a sentiment similarly expressed by the fictional Roy Hobbs in THE NATURAL). Unfortunately, as Ben Bradlee, Jr. points out in graphic detail in the opening and closing chapters of his massive biography, THE KID: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams, this might not be the case.

There’s a strong possibility that even those who don’t follow baseball might be aware of Williams for his grizzly epilogue after he passed away in 2002: He was not buried or cremated (as he had wished), but rather turned into front-page news for being interred in an establishment that deep-freezes clients with the intention of reanimating them in the future. (The “immortal” portion of the title --- intentional or not --- will no doubt remind the book lover of Rebecca Skloot’s similarly titled THE IMMORTAL LIFE OF HENRIETTA LACKS.)

Unfortunately, this coda to an already tumultuous life --- told in gory detail --- might prove distracting in an otherwise thorough discourse of Williams as a Hall of Fame player who had an appreciation for the underdog, since he considered himself one.

"Previous books have played up Williams’s military record; he was a fighter pilot in both World War II and the Korean War. But Bradlee digs beyond the proffered heroics to expose the young man’s true feelings."

His childhood --- the product of a broken home, whose mother preferred her work in a Salvation Army band in San Diego rather than tend to the needs of him and his younger brother --- goes a long way in explaining his make-up (to the armchair psychologist, if Williams was playing these days, I would not be surprised if he had been “classified” with some sort of attention deficit or even bi-polar disorder). Williams was of Mexican descent, which he found shameful during his baseball career, but it may explain his affinity for minority players. He took the opportunity during his Hall of Fame induction speech to politick on behalf of veterans from the Negro Leagues for similar consideration. And as much of a self-promoter as he was as an athlete, he generously gave his time to sick children and charities, although he insisted on keeping such information out of the press, with whom he also had a contentious relationship for his entire career, not being one to suffer fools gladly.

Previous books have played up Williams’s military record; he was a fighter pilot in both World War II and the Korean War. But Bradlee digs beyond the proffered heroics to expose the young man’s true feelings. Like many in his situation --- i.e., athletes in the prime of their physical life who were called to serve their country --- Williams was caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, as the sole provider for his mother, he was qualified for exemption from duty. On the other hand, this was a time when everyone was called upon to make sacrifices, and those who took advantage of such a legitimate loophole were treated with disdain, especially those in the public eye. The government and draft boards were in a similar bind: allow Williams his 3A status, or come across as playing favorite to a celebrity. He was in a similar situation several years later, when he was recalled for active service in Korea. This time was more problematic; Williams was 33 in 1952 when he rejoined the Marines. How many more years could he possibly play, assuming he got through his hitch without being injured or killed?

As wonderful as his playing career might be, an athlete spends more time in retirement than in the game. This is often a period of difficult adjustments. Grappling with a life without constant attention and adulation can be a tough transition, as can finding oneself surrounded by a family he doesn’t know, for all the time spent on the road. Many can’t handle it well, and this becomes a difficult side for the reader to witness.

A book of this heft carries certain expectations. Its weight is measured not just in pages, which is reportedly the most for a book of this type, but where it fits into the collective genre of baseball biography and Williams hagiography.

Bradlee obviously undertook a massive research project in preparation for THE KID, but is bigger necessarily better? Do we really need to know where he lodged during one of his fishing expeditions or what he ate for breakfast (or the shoe size of one of his wives)? That all depends on the readers’ desire for attention to detail. Like the motto of a television news network, “We report. You decide.”

Reviewed by Ron Kaplan on December 20, 2013

The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams

- Publication Date: December 3, 2013

- Genres: Biography, Nonfiction, Sports

- Hardcover: 864 pages

- Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-10: 0316614351

- ISBN-13: 9780316614351