Excerpt

Excerpt

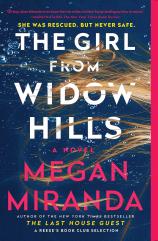

The Girl from Widow Hills

Chapter 1

Wednesday, 7 p.m.

THE BOX SAT AT the foot of the porch steps, in a small clearing of dirt where grass still refused to grow. Cardboard sides left exposed to the elements, my full name written in black marker, the edge of my address just starting to bleed. It fit on my hip, like a child.

I knew she was gone before I woke.

The first line of my mother’s book, the same thing she allegedly told the police when they first arrived. A sentiment repeated in every media interview in the months after the accident, her words transmitted directly into millions of living rooms across the country.

Nearly twenty years later, and this was the refrain now echoing in my head as I carried the box up the wooden porch stairs. The catch in her voice. That familiar cadence.

I shut and locked the front door behind me, took the delivery down the arched hall to the kitchen table. The contents shifted inside, nearly weightless.

It clattered against the table when I set it down, more noise than substance. I went straight for the drawer beside the sink, didn’t prolong the moment to let it gather any more significance.

Box cutter through the triple-layer tape. Corners softened from the moisture still clinging to the ground from yesterday’s rain. The lid wedged tight over the top. A chilled darkness within.

I knew she was gone—

Her words were cliché at best, an untruth at worst—a story crafted in hindsight.

Maybe she truly believed it. I rarely did, unless I was feeling generous—which, at the moment, staring into the sad contents of this half-empty box, I was. Right then, I wanted to believe—believe that, at one point, there had been a tether between my soul and hers, and she could feel something in the absence: a prickle at her neck, her call down the dim hallway that always felt humid, even in winter; my name—Arden?—echoing off the walls, even though she knew—she just knew—there would be no answer; the front door already ajar—the first true sign—and the screen door banging shut behind her as she ran barefoot into the wet grass, still in flannel pajama pants and a fraying, faded T-shirt, screaming my name until her throat went raw. Until the neighbors came. The police. The media.

It was pure intuition. The second line of her book. She knew I was gone. Of course she knew.

Now I wish I could’ve said the same.

Instead of the truth: that my mother had been gone for seven months before I knew it. Knew that she hadn’t just disappeared on a binge, or had her phone disconnected for nonpayment, or found some guy and slipped into his life instead, shedding the skin of her previous one, while I’d just been grateful I hadn’t heard from her in so long.

There was always this lingering fear that, no matter how far I went, no matter how many layers I put between us, she would appear one day like an apparition: that I’d step outside on my way to work one morning, and there she would be, looming on the front porch despite her size, with a too-wide smile and too-skinny arms. Throwing her bony arms around my neck and laughing as if I’d summoned her.

In reality, it took seven months for the truth to reach me, a slow grind of paperwork, and her, always, slipping to the bottom of the pile. An overdose in a county overrun with overdoses, in a state in the middle of flyover country, buried under a growing epidemic. No license in her possession, no address. Unidentified, until somehow they uncovered her name.

Maybe someone came looking for her—a man, face interchangeable with any other man’s. Maybe her prints hit on something new in the system. I didn’t know, and it didn’t matter.

However it happened, they eventually matched her name: Laurel Maynor. And then she waited some more. Until someone looked twice, dug deeper. Maybe she’d been at a hospital sometime in the preceding years; maybe she’d written my name as a contact.

Or perhaps there was no tangible connection at all but a tug at their memory: Wasn’t she that girl’s mother? The girl from Widow Hills? Remembering the story, the headlines. Pulling out my name, tracing it across time and distance through the faintest trail of paperwork.

When the phone rang and they asked for me by my previous name, the one I never used anymore and hadn’t since high school, it still hadn’t sunk in. I hadn’t even had the foresight in the moment before they said it. Is this Arden Maynor, daughter of Laurel Maynor?

Ms. Maynor, I’m afraid we have some bad news.

Even then I thought of something else. My mother, locked up inside a cell, asking me to come bail her out. I had been preparing myself for the wrong emotion, gritting my jaw, steeling my conviction—

She had been dead for seven months, they said. The logistics already taken care of on the county’s dime, after remaining unclaimed for so long. She would no longer need me for anything. There was just the small matter of her personal effects left behind to collect. It was a relief, I was sure, for them to be able to cross her off their list when they scrawled my address over the top of all that was left, triple-sealing it with packing tape, and shipping it halfway across the country, to me.

There was an envelope resting inside the box, an impersonal tally of the contents held within: Clothing; canvas bag; phone; jewelry. But the only item of clothing inside was a green sweater, tattered, with holes at the ends of the sleeves, which I assumed she must’ve been wearing. I didn’t want to imagine how bad a state the rest of her clothes must have been in, if this was the only thing worth sending. Then: an empty bag that was more like a tote, the teeth of the zipper in place but missing the clasp. There once were words printed on the outside, but everything was a gray-blue smudge now, faded and illegible. Under that, the phone. I turned it over in my hand: a flip phone, old and scratched. Probably from ten years earlier, a pay-as-you-go setup.

And at the bottom, inside a plastic bag, a bracelet. I held it in my palm, let the charm fall over the side of my hand so that it swung from its chain that once had been gold but had since oxidized in sections to a greenish-black. The charm, a tiny ballet slipper, was dotted with the smallest glimmer of stone at the center of the bow.

I held my breath, the charm swinging like a metronome, keeping time even as the world went still. A piece of our past that somehow remained, that she’d never sold.

Even the dead could surprise you.

In that moment, holding the fine bracelet, I felt something snap tight in my chest, bridging the gap, the divide. Something between this world and the next.

The bracelet slipped from my palm onto the table, coiling up like a snake. I reached my hands into the bottom of the box again, stretched my fingers into the corners, searching for more.

There was nothing left. The light in the room shifted, as if the curtains had moved. Maybe it was just the trees outside, casting shadows. My own field of vision darkening in a spell of dizziness. I tried to focus, grabbing the edge of the table to hold myself steady. But I heard a rushing sound, as if the room were hollowing itself out.

And I felt it then, just like she said—an emptiness, an absence. The darkness, opening up.

All that remained inside the box was a scent, like earth. I pictured cold rocks and stagnant water—four walls closing in—and took an unconscious step toward the door.

Twenty years ago, I was the girl who had been swept away in the middle of the night during a storm: into the system of pipes under the wooded terrain of Widow Hills. But I’d survived, against all odds, enduring the violence of the surge, keeping my head above water until the flooding mercilessly receded, eventually making my way toward the daylight, grabbing on to a grate—where I was ultimately found. It had taken nearly three days to find me, but the memory of that time was long gone. Lost to youth, or to trauma, or to self-preservation. My mind protecting me, until I couldn’t pull the memory to the surface, even if I wanted to. All that remained was the fear. Of closed walls, of an endless dark, of no way out. An instinct in place of a memory.

My mother used to call us both survivors. For a long time, I believed her.

The scent was probably nothing but the cardboard itself, left exposed to the damp earth and chilled evening. The outside of my own home, brought in.

But for a second, I remembered, like I hadn’t back then or ever since. I remembered the darkness and the cold and my small hand gripped tight on a rusted metal grate. I remembered my own ragged breathing in the silence, and something else, far away. An almost sound. Like I could hear the echo of a yell, my name carried on the wind into the unfathomable darkness—across the miles, under the earth, where I waited to be found.

The Girl from Widow Hills

- Genres: Fiction, Mystery, Psychological Suspense, Psychological Thriller, Suspense, Thriller, Women's Fiction

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- ISBN-10: 1501165437

- ISBN-13: 9781501165436