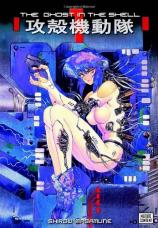

The Ghost in the Shell, Vol. 1

Review

The Ghost in the Shell, Vol. 1

In his brief introduction to this first volume of a landmark series about a cyborg, Dark Horse president Mike Richardson cites all the thematic questions you’d expect—what makes people “human,” what is a soul, are machines capable of authentic emotion? And while Shirow Masamune’s masterful Ghost in the Shell certainly addresses such issues, often in profound ways, it’s worth nothing that Richardson does leave out one question: What are the erotic implications of this blurring between the organic and the synthetic?

It’s not an idle question, but rather one that confronts readers in several different forms, perhaps most obviously when the protagonist, the immanently capable Major Motoko Kusanagi, regularly appears in pinup-style poses. One senses, though, that these are bones thrown to a certain audience segment and, for better or worse, they’re not apt to trouble hetero female readers who may be accustomed to a lot more cheesecake in manga (not to mention mainstream superhero comics). Moreover, it soon becomes apparent that Masamune is playing a much deeper game here as he goes about deliberately undermining the erotic—or at least conventional assumptions about it and conventional approaches to it in comics—by positioning readers to be hit hard by far more disturbing images. In one battle scene, Kusanagi loses an arm at the elbow, metallic tendrils dangling from the stump, and she barely misses a beat—to her, it’s a spare part that can be fixed or replaced, but for readers, it destroys the integrity of the female form and disrupts the pleasure of any passive voyeurism that might be occurring. Similarly, at one point, an asexual cyber-nemesis known as “The Puppeteer” takes refuge in the body of a nude female cyborg and is later interrogated while constrained—but all that remains of her (it?) is the head and topless torso, which is in fact a good example of the “shell” referenced in the title.

A feminist read might contend that this is an instance of objectification in literal, even crude, terms. However, when viewed within the context of Masamune’s thematic concerns, it makes complete sense. If nothing else, The Ghost in the Shell is about “programming” in the word’s broadest possible meaning. That means not only the conflict between outside control versus autonomy in computers, networks, robots, and other cyber-entities, but also in groups and nations (it’s subtly suggested that laws are a form of programming) and, of course, in individuals in that we’re subject to the “instructions” written into us by culture, psychology, and language. Standing apart from this mechanistic view is Masamune’s construct of the “ghost”—a term that roughly translates to “psyche” or “soul.” That’s not to say that ghosts can’t be infiltrated or manipulated by criminal elements like any other part of an apparatus, but rather that this distinction between soul and “mecha” is central to nearly everything that takes place. Readers, too, are naturally going to follow a learned (i.e., installed) “program” when decoding manga or any other text and that includes reading its artwork. So when Masamune provides troubling images that don’t map to our expectations, he is problemating the process and helping readers see our own programming for what it is, as an automatic reaction and not reflective of something essential either about ourselves or the images themselves. And that’s true whether the input stimuli we’re receiving is mildly erotic (it never really exceeds this level) or violent in nature.

That said, it’s not as if the action in The Ghost in the Shell is abstract or presented as a token nod at genre conventions—it’s vigorous, unapologetic, and often thrilling. As Kusanagi leads her small squad of government commandoes against terrorists, hackers, and corporate criminals, the dynamic page layouts and effortlessly fluid storytelling draw us into the firefights and chase sequences like few other works in the medium. However, on a scale that may be unparalleled in graphic fiction, there’s also a tremendous density of ideas. Sometimes, as if realizing the challenge of delivering on both tracks, Masamune includes footnote-like clarifications in the gutters so as not to slow things down with expository dialogue or caption boxes. Then, as a bonus treat, there’s a 14-page section of author’s notes in the book’s backmatter that’s keyed to specific pages, with the creator providing annotations on his work that make for fascinating reading in their own right.

It’s this combination of brain and brawn that causes The Ghost in the Shell to appeal, as the saying goes, to both the head and the heart. But that’s not all. As the first volume concludes Masamune takes things in a wholly different direction: While the story has been rubbing up against the metaphysical throughout, in the final chapter, it breaks all the way through and goes for the out-and-out mystical. There’s not much I can say that won’t ruin things for newcomers to the franchise, so I’ll leave it at that. In short, Ghost in the Shellis hard sci-fi of the best possible sort: the type that’s so full of both undiluted artfulness and philosophy that it’s arguably a must-read even for those who don’t usually take to the genre.

Reviewed by Peter Gutiérrez on October 13, 2009

The Ghost in the Shell, Vol. 1

- Publication Date: October 13, 2009

- Paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: Kodansha Comics

- ISBN-10: 1935429019

- ISBN-13: 9781935429012