Excerpt

Excerpt

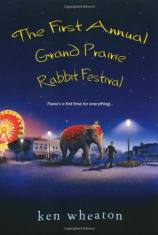

The First Annual Grand Prairie Rabbit Festival

Chapter 1

The counter clerk at T-Ron’s Grab ’n’ Go doesn’t bat an eye when I ask for two packs of Camel Lights, a bag of pork cracklin’s, and a pint of Crown Royal. Is it every day she’s confronted with a priest --- black pants, black shirt, white collar and all --- buying whiskey and cracklin’s before lunch?

The cigarettes are mine, the rest is for Miss Rita, who’s finishing out life in Easy Time Nursing Home, where the staff frowns upon booze and pigskin. Before I walk in, I place my purchases into my black leather satchel, alongside a Bible, a Daily Missal, and last week’s copy of People magazine.

“Hey, Father Steve,” the receptionist says when I enter Easy Time’s lobby, which is covered in the chintzy sort of Thanksgiving decorations you’d expect to see in a preschool or kindergarten. She’s a short, chunky girl with a curly helmet of dull brown hair and an overly pleasant smile. She strikes me as the type who, unable to find a suitable man and unwilling to settle for an unsuitable one, has come to a place where she’ll be appreciated and adored, where she can dole out a little of that love pent up in an otherwise lonely life. I wonder if she lives in a trailer full of cats.

“Hi, Marie. How you doing today, cher?” I don’t know why I put on the Cajun schtick for her, but I do.

“Aw, I’m doing good, and you?” she chirps. I swear her teeth just might explode right out of her head.

“Comme ci, comme ça,” I answer. “Can’t complain. How’s Miss Rita doing today?”

“Oh, she’s good today. She’s awake and sitting in her room.”

As opposed to what? Hopping around the grounds on her one leg? Playing roller hockey in the parking lot?

“Good, good. I’ll see you later, Marie.”

Miss Rita, as far as anyone can tell, is somewhere between 105 and 117 years old. No birth certificate. Her “birthday” rolls around in late November, early December and seems to fall on whatever day is convenient for Easy Time and the reporters who cover the occasion. Her grandchildren don’t mind. Miss Rita doesn’t, either, as long as someone makes a fuss over it.

Aside from one dutiful grandson, I’m Miss Rita’s only regular visitor. She’s not a member of my parish --- St. Pete’s doesn’t have a single black parishioner --- but she’s practically a member of my family. Miss Rita was “the help” Pawpaw hired for Mawmaw back in the days when it was still acceptable to call people “the help.”

I remember Miss Rita and Mawmaw sitting in Mawmaw’s kitchen, in a pair of old wooden rocking chairs, Miss Rita shiny black to the point of being purple, Mawmaw white and liver-spotted. They rocked in a counterrhythm, black forward, white back, white forward, black back, all day long watching soap operas. Soul poppers, Miss Rita called them. I guess there was plenty Miss Rita helped Mawmaw with --- folding laundry, shelling peas, collecting eggs from the chickens, peeling shrimp. But I remember them most clearly in those chairs, rocking away and arguing about the existence of evil twins.

Mawmaw died when I was twelve and Miss Rita went right on living. Now Miss Rita spends her days in a nursing home, sitting one-legged in a wheelchair, watching TV alone. The newspaper reporters invariably describe her as slightly incoherent but happy, like a retarded child who doesn’t know she’s been handed a tough lot in life.

Daddy used to visit her a lot, which is where I picked up the habit, but not so much since he remarried fourteen years ago. I asked him about it once, but he didn’t want to talk about it.

I walk into Miss Rita’s room. She’s facing the window, her head thrown back on her shoulders, eyes closed, mouth opened, a little string of drool hanging down onto the T-shirt she’s wearing --- a wet splotch sits right in the middle of Malcolm X’s forehead. Not quite what he had in mind when he uttered the words printed on the shirt: “By any means necessary.” The left leg of her jeans is rolled up and pinned to where the knee should be. It’s what she’s worn since the amputation ten years ago. The orderlies would prefer her to wear a robe or a housedress, but I’m sure they found it easier to let her have her way. Her skin’s faded in her old age to the color of dirt, and sitting there like that, she looks like a piece of discarded furniture.

A rap song blurts from the radio; every other word is bleeped out for airplay and I can still make out the phrase “Bitch, I’ma kill you.” One of the orderlies must have been listening to it. I twist the radio’s volume knob and Miss Rita moves.

“Boy, you better put my program back on.” Her voice is a whisper of its former self, but it still demands respect. She told me once when I was a child, “Never, ever fear no man. You fear God, but no man. God. And Miss Rita, too. Boy, you better watch out for me, too.”

“You sure you don’t want some Cajun or zydeco music, Miss Rita?”

“Yeah, I’m sure I don’t want no Cajun or zydeco music. Your mawmaw made me listen to that for thirty years. Tired of that noise. Now put that radio back on 95.5 before --- ” she says, but falls silent as the door swings open and Marie pokes her head in. “Yall doing okay?”

“Just fine,” I say. Miss Rita’s head falls to her chest. She’s all smile and drool and babbling while she picks at some imaginary spot on her T-shirt. “Just having ourselves a little visit.”

When the door closes, Miss Rita’s head snaps back up. “You bring my stuff?”

“Yeah, I brought it. You sure you should be drinking this?”

“You sure you should be putting your pecker in them little boys’ behinds?” she shoots back at me, and starts cackling.

“Now, c’mon, Miss Rita,” I say, blushing for no good reason.

“Now, c’mon nothing. You quit bugging me about my little medicine, then. Same thing every time. I’m the one a hundred years old. Think I know what I should and shouldn’t do. Lotta good not drinking did your mawmaw.”

“But what about the cracklin’s? All that salt and fat. You don’t even have teeth to chew them with.”

“I got gums. All I need. Now give.” I hand her the bottle in its little purple sack and the brown bag already going transparent from the grease. “All them years of dumping them bowls of okry gumbo your mawmaw tried to force you to eat and this is the thanks I get? You getting on my case all the time?”

She has me there. She was my only ally in the battle against Mawmaw and her okra gumbo. Any other gumbo I loved --- chicken and sausage, gizzard and hearts, seafood, squirrel. But okra? No way. I could write sermons about the pure evil that is okra. Fry it, sauté it, cover it in sugar and chocolate, or wrap it in bacon, but no way is anyone going to convince me that okra, especially in its slimy gumbo manifestation, isn’t concrete proof that Satan walks the earth.

Miss Rita’s hands stop trembling after she takes possession of her gifts. I half expect her eyes to bug out and for her to start hissing and talking about her “precious.”

Strong from years of work --- picking cotton, shelling peas, snapping beans, smacking kids --- her fingers make quick work of the plastic seal and cap on the bottle. I remember those fingers taking hold of my ear and dragging me off for a switching.

She takes a slow pull, says, “Ahhhh,” and smacks her lips before placing the purple Crown Royal bag into a cookie tin with a nest of others like it. I wonder who her connection was while I was away at seminary, but I don’t bother asking. “None of your damn business,” is the reply I’d get.

She takes another pull from the bottle and pops a cracklin’ into her mouth, rolls it around, and sucks on it noisily.

“Mmmmmmm-mmm. Never get tired of that,” she says, slapping her knee.

Our little ritual over, she turns her full attention to me.

“Now, what’s your problem, boy?” She nods at a calendar on the wall. A twenty-something black man in a fireman’s hat and a Speedo lies stretched out on a rock. “You a week early for your regular visit.”

“I can’t come at other times?” I counter.

“You can come any time you want, as long as you remember to bring me something. Now, what’s your problem?”

“I don’t know,” I say. And I don’t. Well, I do. Kind of. Three months into my first solo assignment, just twenty minutes up the road in Grand Prairie, Louisiana, I’ve grown bored. Absolutely and utterly bored. But I didn’t come here to whine about malaise to a woman whose mother was born a slave.

No. The problem is boredom leads to other problems of the heart and soul and mind --- or, in my case, the optical system. I’ve been seeing things. Well, one thing in particular: a red blur flitting around the church, always near the edge of the grounds, in the trees or by the road. I’m pretty sure it’s not a ghost. If it is, it’s a peculiar one that avoids the cemetery and the inside of the church. At first, I told myself it was simply a trick of the eye --- a butterfly flitting by, a red leaf on the wind. Lately, I’ve grown partial to the theory that it’s a symptom of a massive brain tumor. I can all too easily imagine how Miss Rita’s going to respond.

But there’s no need --- or time --- to explain. She’s quick with her own conclusion: “What you need is a woman.” She points a bony finger at me.

A woman? Mama doesn’t even bring that one up anymore. Besides, that’s the last thing on my mind. A woman? That part of my mind has been cauterized.

“Can’t have a woman,” I say.

“Don’t matter. You still need one.”

“Well, it does matter. I’m a priest. Can’t have one.”

“Them Baptist preachers over at Zion got women. Hell, that main one there got him three or four from what I hear.”

“Them Baptist preachers don’t let their people drink.”

She pauses for a moment, takes another sip, and fixes her eyes on me. “I bet you a woman do you a lot more better than a beer anyway.”

“Hmmph,” is all I can think to say.

“You not one of them likes men or little boys?”

“No, Miss Rita,” I snap.

“Hey, now. Just checking. You never know these days. You never know. But Lord, it’d kill your mawmaw if she wasn’t dead already.”

“Well, she’d be fine because I’m not.”

“There’s your problem, then. Need a woman. Ain’t natural for a man to be without a woman. Bible says so.”

“The Church says --- ” I start.

“The Church nothing. I had the Bible read to me about five thousand times in my life. Ain’t a damn thing in there about priests not getting married.”

When did she become a theologian? Of course, she’s right. Nothing in the Bible about it at all.

“Look. I can’t. Okay? It’s the rules. That simple.”

“Hmmph. Rules say you can’t have altar girls, either.”

She glares at me. I glare back. I never told her about the altar girls. Which means I’ve become a rumor already. The new priest in Grand Prairie adding another chapter of crazy to that little town’s history. She pops another cracklin’ in her mouth and takes another swig of whiskey. She wipes her mouth with the back of her hand, bobs her head in rhythm with the hip-hop coming out of the radio.

“There’s nothing in the rules against altar girls,” I say. “Besides, I couldn’t find any boys.”

“Wonder why,” she says. “Some strange man living alone in the woods without a wife. I wouldn’t let my sons go around him, either. People read them stories, you know.”

“But they trust me with their daughters?” I say, knowing full well what the response is.

“Probably didn’t even cross their mind you’d be interested,” she says, laughing again.

At this point, she’s already enjoying herself at my expense far too much, so I decide to save my ghost story for another time. “I’m sure there are other good explanations,” I say, not entirely convinced myself.

“There always is an explanation, isn’t there? Well, I got a simple one for you. You need a woman.”

The last thing I want lousing up my life is a woman. I don’t want one and don’t need one. Miss Rita is wrong about that. Wrong as a Scientologist. Forget the rules of the Church. I like my life simple, and simplicity is the last thing I associate with women.

Yet now, at this very minute, I have two women-in-training traipsing about my altar, their fruit-scented shampoos making it next to impossible to stay in that space I inhabit when I’m saying Mass --- the zone, if you will.

I’d waited a month, an entire month, before asking for altar boys. To be honest, I don’t really need them. But the altar felt naked without them. Besides, the priests in all the other parishes have them. So I put a notice in the church bulletin and made a few announcements during Mass.

The following Monday, a young girl with strawberry blond hair knocked on my door.

“Yes, my child?” I asked in my most priestly voice, immediately feeling like an ass. Thirty-two years old and there I was saying, “Yes, my child?”

“Mama sent me to help you. Daddy said it was okay.”

“Help me? With what?”

“I don’t know,” she said, shrugging. Her thick accent made it sound like a one-word question, Ahduhno? “With the altar and stuff, I guess.”

“Really?” was the only thing I could think to say. I had her write her name and number down and told her I’d call. Denise Fontenot. She dotted the I in Denise with a heart.

Five more girls followed, all about thirteen. Two for each Mass. Not one single boy.

And now, instead of focusing on the Blessed Sacrament of the Eucharist, I’m overly aware of my surroundings.

This is not a good thing in St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in Grand Prairie, Louisiana. Doubly so at the Saturday evening Mass, when the old-timers stroll in out of the woods.

For example, in any other congregation, the old man burping in the fifth pew, on my right hand side, would send a ripple of arched eyebrows, turned heads, and covered giggles through the church. But not here. Mr. Boudreaux can sit there and let one rip, his big owl eyes blinking away like all’s just peachy keen.

Then a fart echoes from one of the pews to my left.

No one seems fazed by this. The only two people in St. Peter’s who seem to notice at all are the Smith boys, who attend twice a month when they’re visiting their father out here in the sticks. I feel for those two boys, spending a Saturday night in the Grand

Prairie wilderness while their friends are getting pizza delivered to their front doors in Opelousas.

Opelousas, twenty minutes down the road via the Ville Platte Highway, is where I grew up. With a population of fifteen thousand people, we were a veritable metropolis. And we had a name for places like Grand Prairie: Bumfuck, Egypt. Bumfuck. A good word to be thinking while saying Mass. Good work. The Lord, no doubt, is smiling upon me.

Luckily, the seminary doesn’t just toss you into the world without a lot of practice, and the words coming out of my mouth are holy, sanctified, and expected.

“Bless and approve our offering. Make it acceptable to You, an offering in Spirit and Truth.” (And please, God, forgive me for my wandering mind and for Your sake, my sake, the congregation’s sake, get me back on track here. Have that little white bird of yours flit back down here and roost in my head.)

But the truth is, once I lose the path, it’s hard to regain. While my mouth keeps motoring along, my mind wanders.

The church building itself doesn’t help. Of all the churches in all the towns in Louisiana. I was hoping for a cathedral; I got stuck with a gussied-up bingo hall, one of those unfortunate low-ceilinged ’60s constructions. The heavy timber beams bracing the roof are the only things even remotely “majestic” about it. Threadbare carpeting covers creaky wooden floorboards. The Way of the Cross marches down either wall in simple formation. There they are, the last, most painful hours of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ done up in fourteen plastic “sculptures” all made in Taiwan.

Near the main entry is the church’s namesake, St. Pete, concrete done up in paint, his eyes directed woefully toward the scrawny but suitably gruesome crucifix suspended by wire directly above me.

“Let it become for us the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ, Your own Son, our Lord,” I say.

St. Pete’s eyes bug me. Too much like an understudy watching the lead actor onstage, mesmerized by his idol but hoping for a tragic accident all the same. I’m tempted at times to wheel that statue of St. Pete out to the front of the church, where an older version of himself, this one done in white plaster, is nailed to an upside-down cross. That’ll show him. But who knows? Maybe he’d be glad to see it. Maybe it would tickle him to know that when we were kids we were convinced the upsidedown crucifix was the welcome shingle for a satanic cult. But I doubt it. St. Peter never struck me as the type to have much of a sense of humor.

To my right and facing the gathered flock is Mother Mary. Now, her, I like. She’s the one truly beautiful thing in the church. Carved out of cedar and stained rather than painted, she still manages to be more realistic than the rest of the lot --- like her husband shoved off in the corner, an afterthought done up in faux marble and chipped paint. In the right light, Mary outshines the tabernacle, which comes as no surprise. I’m not going to admit this sort of thing to some born-again Pentecostal, but in these rural parishes, Mary carries the load. In her simplicity, she sits above that enigmatic Trinity of her Son, His Father, and that little white bird --- or whatever it is people imagine the Holy Ghost to be. I spent kindergarten through twelfth grade at a Catholic school, went to seminary to become a priest, and I still have problems wrapping my mind around the Holy Trinity. But everyone understands a mother’s capacity for love and forgiveness --- and her power over her child.

Mr. Boudreaux burps again, and the Smith boys look at each other, eyes wide and betraying thoughts of strangling their daddy while he sleeps. Divorcing their mother was one thing. Dragging them to this place is unforgivable.

Mr. Devillier, one pew in front of Mr. Boudreaux and three people over, jams his pinky into his ear and gives it a good shake before pulling it out and studying his fingernail.

“Take this, all of you, and eat it,” I say.

So much for the miracle of Transubstantiation.

I wrap up the Eucharistic Prayer, lead the flock through the Lord’s Prayer, and make it to the Breaking of the Bread with no incident.

“This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world,” I say. I hold up the jumbo wafer for all to see. “Happy are those who are called to His supper.”

“Lord, I am not worthy to receive you,” they all reply like good little lambs. “But only say the word and I shall be healed.”

I break the wafer into the platter that holds the smaller, uniform ones I’ll administer during Holy Communion. I chew and swallow my piece and I feel a calm working through me. I wouldn’t expect some random heathen or some Bible-thumping Tammy Faye to believe or understand. A runner, maybe. I’ve heard of runner’s high and that’s how I try to describe it, although I’ve never run anywhere near far enough to experience anything more than runner’s aches, runner’s cramps, and runner’s vomiting. But whatever it is, it’s working. I can feel I’m slipping back into my zone, my plane of worship.

I reach for the wine chalice, bring it to my lips, and, bam! I’ve lost it again.

Grape juice! Son of a bitch!

It’s all I can do not to wince. I never did like grape juice. Vile, nasty, sickly sweet purple scourge of the fruit-juice set. Yes. I know. By this point in the ceremony, it’s supposed to be the blood of Jesus, and the flavor shouldn’t matter.

But still.

I shoot a glance over the chalice rim at Denise Fontenot, standing there decked out in the white robes that belong on a nice, obedient, unscented altar boy.

She’s the one, the thorn in my side. The very picture of innocence if she weren’t Satan incarnate. I swear she was watching me for a reaction just now. There’s no other explanation.

She had to have switched it purposely. Or else she somehow, impossibly, after being told twice before, confused my cardboard box of Franzia with one of the plastic bottles of grape juice that dear departed Father Carrier left behind.

I suffer through the rest of the grape juice. It’s not even good grape juice --- if there is such a thing. It’s that Sam’s Choice garbage from Walmart. I shudder to think where Walmart gets its grapes.

Bad wine I can stomach. I belonged to a group in seminary who theorized that Transubstantiation was all the more miraculous if you had to turn really cheap wine into the Blood of Christ. One guy, who was probably a self-flagellating Calvinist in a previous life, planned to torture himself weekly with Thunder-bird (Fortified by Christ!) even if it did render him blind within a year. Grape juice was the last resort of recovering alcoholics, God have mercy on their souls.

As I wipe the rim of the chalice, I look over at Denise again. Is that a smirk? I look over at the other altar girl, Maggie Deshotel, for some sort of comparison. But as usual, she simply seems sleepy. I worry that one of these days she’s going to pitch right over, split her head open, and I’ll have little-girl blood pooling all over the sacred altar of Jesus. I look back at Denise, who seems very pleased with herself.

Denise has been acting a little weird lately. Squirrely, maybe? Or kittenish? Is that the word I don’t want to acknowledge? She’s been bumping into me on the altar. Her palms have been a little clammy, her grip a little too firm, a little too slow on the release during the Sign of Peace. Or maybe I’ve just lost my mind. Maybe I’m just imagining these things.

I manage to conclude Mass without verbalizing anything I’m actually thinking. I hate to run things on autopilot, but at the moment I’m more than thankful for the ability. I follow the two girls down the aisle and through the front doors. Denise hugs me around the waist --- a new development --- says “Bye, Father Steve,” and runs off with Maggie.

I make my usual round of handshakes, hugs, and headpats. The old men say little. A handshake and maybe a “How you, Father?” or a “Comment ca¸ va?” before going to their trucks and Suburbans, where they stand around talking the serious business of farming, hunting, and dirty jokes. Their wives stay behind, clucking with each other and fighting for my attention.

This is a fine art, this making old women happy, playing to their individual egos without permanently offending the rest of the gaggle. In a way, I’m their rock star, they are my groupies.

Tonight, I have to thank Miss Robichaux for the pork roast she dropped off this afternoon. While I’m doing this, I notice Denise and Maggie, now in jeans and baby tees, being chased through the parking lot by Sammy Guidry, a gangly boy still at an age where he hasn’t figured out why he’s been chasing girls his whole life, an age where he wouldn’t know what to do with one if he caught one. Both of the girls are laughing, their cheeks red. I’m watching this action over Miss Robichaux’s head when Denise looks directly at me.

“I’ll tell you a secret, Miss Robichaux,” I say, returning my eyes to hers, stage-whispering loud enough for her friends to hear. “That was the best --- and I mean the best --- piece of pig I ever had in my life. And don’t you go repeating that anywhere near Opelousas, because my mama’d like to kill me if she heard me saying that.”

Miss Robichaux blushes and giggles. Even through the Avon base she has caked on, her cheeks turn the same gaudy red she’s died her hair. It’s the same look Mawmaw wore to church when she was alive --- Louisiana old lady.

“Aw, now, Father. You stop that,” she says, and makes a show of slapping my chest, a bit of the teenager she once was apparent in that gesture.

After the crowd departs, I stand alone in the parking lot watching the sun set over the graveyard, a small intimate plot just to the west of the church. Only a few of its bodies are shelved aboveground. The land here is high enough, the water table low enough, that we don’t have to worry about flash floods filling the graves and squirting fifty-year-old caskets out of the ground like watermelon seeds from the mouths of children.

This has become common practice for me, standing here after Saturday evening Mass, watching the sun set through the moss-draped live oaks, painting the headstones a soft salmon color.

A car pulls into the lot behind me. I don’t turn to face it. I know it will stop five inches from me. I can feel the heat of its grill on the back of my legs. When the door opens, I hear the distinctive bling-blong, bling-blong of a mid-’90s Buick.

“Hey, Vick,” I say as she slides up next to me. She hands me a lit cigarette.

I give her a once-over before turning back to watch the sunset. She’s wearing jeans and an unbuttoned man’s jacket over a white tee. Her blond hair just barely reaches her shoulders and her dark skin looks good in the dying light. She’s a smidge taller than me, but I don’t hold it against her.

“What’s on the agenda tonight?” she asks.

“Just a silent moment of reflection.”

“Mass a bit of a distraction?”

I don’t know how she does this. I’ve known her for only three months, but she seems to have the ability to read me like a book, a book not all that complex or layered, a catalog maybe.

“Denise give you grape juice again?” is her follow-up question.

“Yup.”

“I told you to throw it all out.”

We watch the top edge of the sun slip below the horizon.

“She hugged me tonight.”

This, Vicky finds hilarious.

“Don’t know what we’re going to do with you, Padre.” She likes to do that, use cute little priest names for me. She’s a little over-comfortable around priests, probably because she’s the daughter of the last one who worked here.

I’m still trying to wrap my head around that one. Vicky’s my age. We’d heard rumors of her existence over in Opelousas when I was a kid. But rumors are a dime a dozen the world over and go at an even cheaper rate down in these parts. It’s one thing to hear a rumor, another to meet one.

It’s her old man I replaced, so she’s been helpful, my own Encyclopedia Grand Prairieca, Chamber of Commerce, and default St. Pete’s church lady.

But she can also be a big pain in the ass.

“I told you not to try getting altar boys,” she says, pulling a beer out of her jacket pocket and offering it to me. “Daddy didn’t use any.”

“I figured Father Carrier didn’t use altar boys because he saw it as an unnecessary luxury.”

“Daddy? Ha.”

Daddy. The word didn’t sound right coming out of her mouth. It sounded like the wrong answer to a bad brain teaser. What can always be a father but never a daddy? A priest. Then Paul Carrier went and screwed everything up (not that he was the first by any stretch of the imagination). When I heard Vicky say Daddy, I imagined some sort of reverse virgin birth, something out of Greek mythology. Father Carrier still full of youth, but lonely in his marriage to Christ, shuffling to the tabernacle on Sunday morning wondering if he can stand an entire lifetime in this profession. He opens the tabernacle door and, lo, within is a girl child, cooing and giggling at him. Of course, that’s not the way it happened at all; Father Carrier preferred to conceive his child the old-fashioned way.

“Daddy,” she was saying. “He might have said something like that. But he would have had seven or eight of them little bastards up there at one time if he could have found them. Hell, this was the same man who replaced the priest’s chair with a La-Z-Boy.”

“Why didn’t he use girls?”

“I think Daddy had enough on his hands with me. Also, it’s just not a bright idea to put pubescent girls in the same room with a horny old goat.”

“Now, just a minute,” I protest.

“Simmer down, sailor,” she says, laughing again. “I was talking about Daddy. Then again, them little girls running around that altar seem to get your blood boiling.” Her hands are in her pockets now. She rolls up onto her toes, then back to her heels a couple of times. It’s sort of a mannish gesture, one that says, “Yes, my boy, I know you’re in a pickle and I’m just pleased as I can be about the whole thing.”

“Give me a little credit, Vick.”

“All I’m saying is it can’t be easy.”

“That’s part of the point, I think. It’s not supposed to be easy. Besides, I made it this long, I think I can make it another thirty years.”

“You expect me to believe you’ve gone your whole life without?”

“I expect you to believe what I tell you,” I say, giving her what I imagine to be a rakish grin.

“Okay, stop that. You look like you’re in pain. But, seriously, another thirty years? You’re not giving yourself a very long life.”

“I’m hoping the equipment will give out by then and I won’t have to worry about it anymore.”

She laughs. I laugh. But I’m not joking half as much as she thinks I am.

“Well, I’m going inside,” I say. “Going to watch Touched by an Angel or something.”

“So that’s what angels are for?” she says, trying to keep a straight face but failing miserably. I would have laughed --- I walked right into that one --- but she’s so pleased with herself that she’s bending over at the waist and laughing too hard at her own joke.

“Shit, Padre,” she says. “Sorry. I couldn’t help myself.”

I turn away and face the one streetlight in the parking lot, where the nightly drama of bats chasing moths is unfolding.

“Aw, c’mon, Steve. Look, I’m sorry. I’m just messing with you. That was a good one. You have to give me that much.” She’s almost pleading.

“Okay. It’s a good one. Ha. Ha. Now I’m going inside. You’re more than welcome to come in.”

She stands straight. “I’d love to join you, but I have to head into town. Big Saturday night.”

When was the last time I had a big Saturday night? When was the last time I had a Saturday night?

She picks a moth off my shoulder. After releasing it, she smoothes out the spot on my robe where it was sitting. “Yeah, I promised Mama and the girls I’d go play cards with them.”

Oddly enough, I find it harder to imagine her mother, a woman I’ve actually met, than her father. Grace was never more than a minor character in the rumor, so maybe that’s why it’s hard to deal with her in terms of reality. It would be like running into Jesus one day and when he introduces you to a parent, you get stuck with Joseph instead of Mary.

We say our good-byes and she drives off into the night. As she’s pulling out of the driveway, I see the flit of red again, this time across the highway about half a mile down in the gathering shadows of dusk. For a second, it looked like a girl wearing a red cape and hood. But just like that, it’s gone. I rub my eyes, blink, and look again. Nothing. Probably just residual red in my eyes from Vicky’s taillights.

I go to the vestry and help myself to a large glass of unblessed Franzia before putting away my overlay, taking off my collar, and heading to the rectory.

Chapter 2

They told me before my placement to expect such moments, that I’d get a little loopy sometime around the fifth month, sooner if plopped into a small rural parish. I’m nothing if not punctual. There’s even a hotline I can call.

One of the seminary instructors, Father Benjamin Snyder, had warned me of the “dangers” of working in a small parish.

I laughed in his face. “You’re kidding me, right? Priests back home are minor celebrities,” I said. “They get fat on the meals cooked just for them. Besides which, every town in Louisiana has more than one church. I can always just hang out with the other priests. Just like here.”

“You’ll see,” Father Snyder had said, with a thousand-yard stare that should have been warning enough. “You’ll see.”

Oh yes, I have seen.

First, I saw my blind spot. Yes, proper towns have more than one church. But if Louisiana lacks one thing, it’s an abundance of real towns. How could I have forgotten this? As a kid, I was dragged around the state to one godforsaken hamlet after another in the service of visiting distant relatives with my dad, the family’s self-appointed missionary. Those little towns. Three intersections, one convenience store, and, halfway between one village and the next, the church they shared. It inspired in me an overwhelming claustrophobia --- or was it agoraphobia? --- and a need to escape to something grand.

I got grand all right.

Grand Prairie. Plenty of horses. One church. We don’t even have a convenience store. I have to drive fifteen minutes to get a Coke and a pack of Camels.

And yes, I’m a minor celebrity. I was right about that much, at least. I don’t cook for myself because these old women can’t get enough of me. They send their husbands to take care of the church lawn, their grandkids to wash my car.

But what’s becoming increasingly clear is that I’m the shepherd of a flock that does little more than the requisite bahhing. They’re good people. Good and simple. Good and simple and boring. My Dear Lord, forgive me, but, man, are they boring!

I suspect that’s what Father Snyder, who himself had served a small-town church for twenty-five years, had been trying to warn me about.

If nothing else, I expected to be tutored in the ways of the common man, schooled in the philosophy of folk wisdom. But either movies about common folk are far, far off base or the good people of Grand Prairie aren’t living up to their part of the bargain. They farm, go to work in Opelousas, eat too much, sleep just enough, and spend time with their families. Some have an easy time of it, others make a mess of it. But no one seems to be following a secret code of simple people.

And other priests? Of the four in Opelousas and the three in Ville Platte, five are too busy with their big fancy parishes, with all those weddings and baptisms and confirmations and funerals. Another is about as stimulating as decaffeinated coffee and carries on way too much about his mother. And the seventh is a black separatist trying to break from Holy Mother Church while still keeping the church and school buildings for some sort of Black Power commune.

So it’s just me. Sometimes Vicky. Sometimes the red thing. I attend to my duties, flirt with the old women who drop by, and stay up too late watching bad TV or surfing the Web. Then I’m up at the crack of dawn for prayers and morning Mass, which is always attended by the same four people: the Holy Trinity and me. It’s actually rather nice, the ritual of it, the familiarity of it. But to be honest, I get a little creeped out by the echo of my own voice bouncing around the otherwise silent church. Every time the building settles, I flinch and look around to spot the source of the sound, as if I’ll find a ghost in a red sheet bumping around the place or one of the statues taking a leisurely stroll through the pews.

When I first started at St. Peter’s, a couple of the hard-core biddies showed up for morning Mass. But there was something slightly embarrassing about it. In a cathedral of appropriate size, there’s enough room for each person to create her own personal buffer. But in St. Pete’s it feels like we’re sharing an intimate moment. The prayers take on the hushed tones of a seduction, the call-and-response portion of some sort of holy, private flirtation. One morning, I made eye contact with Miss Emilia Boudreaux and a blush bloomed from her neckline straight up to the roots of her hair. They’d all rather flirt outside of Mass, I guess, because she quit showing up after that, and so did the others.

So now I have the Masses all to myself. It took some getting used to at first. Sitting alone and silent for the Adoration of the Eucharist is one thing --- chilling with the J-man, we called it back in seminary. You sit or kneel in private with the Eucharist, wrapped in silence, contemplating Christ --- or, depending on your lack of focus, the art on the wall, how funny chimpanzees are, or whether ghosts really do exist because you swear you just heard something moving in the dark corner of the church for the fifth time.

Mass is different. It involves at least thirty minutes of formalized religious ceremony and public speaking --- minus the public.

When I first did it alone, I was overly conscious of my movements and how silly I must look, raising my arms up into the air, praying out loud, and saying, “Peace be with you,” the only response the dead-eyed stares of the sculpted saints. As time went on, it felt less like mental masturbation and more like meditation. Now it seems an especially tranquil way to start the day.

This morning starts out no differently and finds me standing in an empty church reading aloud to myself from 1 Corinthians.

That’s a meaty one, all about spiritual perception and receiving wisdom and those in the world who are limited to believing only what they can see with their eyes, touch with their hands. Some folks always think of scientists when reading this passage, but in my limited experience with scientists, many of them seem to feel like the more they learn, the less they know.

The Gospel reading is from Luke, in which Jesus goes down to Capernaum and starts casting demons out left and right.

Then I see it.

A little girl, all in red, her pale white face pressed to the door, her dull eyes staring, staring.

“Son of a bitch,” I say, dropping the Bible to the floor.

“Shit,” I say, and bend immediately down to pick up the Good Book, my hands shaking violently. When I stand up, it --- She --- is gone. I run to the front door. Another flash. Off to the left on the highway. That’s it. I’m getting to the bottom of this. I run out to the car. I don’t have my keys. I always take them out of my pocket so that they don’t jingle during Mass. “Fuck,” I whisper, and run back into the church. As I’m doing so, I hear a faint clopping sound drawing near. “No, no, no. Not today,” I mutter, casting about wildly for my keys. But once I find them and get back out to the car, the clopping --- hooves on asphalt --- is distinctively clear and growing closer.

By the time I have the car backed up and turned around, it’s too late. Lem Landry and his horse-drawn hay wagon are upon me, cruising down the highway at a blistering five miles per hour. Bastard. Once a year, a reporter-slash-photographer from the Daily World will trek out from Opelousas to take a picture of Lem going down a dirt road in his wagon. And Lem, in excruciatingly broken English, will smile and tell the reporter how Lem’s granddaddy made the wagon by hand and how he, Lem, lives in the woods and survives on the squirrel, rabbit, and catfish he kills or catches and whatever his wife grows in the backyard. And he always apologizes for his bad English “ ’cause we don’t got much use for it back here.”

I wonder why the paper doesn’t just keep the story on file instead of sending someone out every year to be lied to. Because it is a lie. And not just a little lie. To borrow an expression common to the area, it’s a damn lie.

As anyone in Grand Prairie could tell any reporter interested in doing more than a fuzzy feature piece, Lem Landry bought that wagon at a flea market in 1972 and pulled it home with a truck. In fact, sitting in Lem Landry’s driveway at this very moment is a sparkling red Ford F-250 Super Cab, which complements his true sweetheart, a 1973 Thunderbird that he drives once a week to Walmart, not half a mile from the offices of the Daily World. Once he gets to Walmart, he sits in the concession area with a bunch of other old farts and shovels the bullshit until it’s knee-deep. Furthermore, said shit-shoveling is done in perfectly fine English, the only flaw being that Lem never did get a firm grasp of correct pronoun usage, referring to everyone and everything as “he,” even if speaking about a “she” or an “it.”

Lem prefers Popeyes fried chicken to squirrel and, from what I hear, will only eat squirrel if someone else kills, cleans, and cooks it for him. His wife grows nothing in any yard, gardening being a tough hobby for a woman who’s never existed in the first place. Lem, in fact, had been an incorrigible womanizer well into his fifties, taking advantage of the fact that many of the men around here worked two-weeks-on/one-week off schedules in the oil fields during the boom years. One of the truly amazing things about Lem is that he’d never been shot and left for dead in the woods of Grand Prairie.

Even calling the hay wagon horse-drawn is a bit of a stretch considering Lem insists on using the most stubborn mules he can find. It’s as if he goes to farmers’ auctions with an eye for the slowest unmovable animals created by God. He even admits that if mules could be bred, he’d get in the business and breed the stubbornest animal he could create just because the entire idea, like suckering newspaper reporters, strikes him as a great laugh.

What also strikes him as a great laugh is driving his buggy down the center line of the highway, seeing how many cars he can get to pile up behind him. Today he’s already got a string of six. So even if I got on the highway behind them, it would be nearly impossible to pass them all. That’s assuming the red thing is something real, something that can be followed.

So I get out of the car and wave at Lem and the passing parade. Then I head back into the church to finish the interrupted Mass. I mutter my way through the rest of it, embarrassed that I’d let myself get so scared. Even so, I can’t help but keep one eye on the door to see if it comes back.

After Mass, I clean up the altar, then halfheartedly clean up the rectory before heading over to the home of Miss Velma Richard for an early lunch.

I’ve been dreading this one, using all my other invites as excuses, putting off Miss Velma again and again until finally guilt got the better of me.

The thing is, Miss Velma smells familiar. Mothballs, cigarette smoke, and canned cat food. It’s the smell of old, the smell of loneliness, the smell of defeat. And the Avon perfume she douses herself with for church can’t hide that. It’s something worse than nursing home; it reeks of shut-in.

Even the other old birds sort of shun her. They’re polite, sure. But after Mass, Miss Velma is always that person just outside the group, standing on tiptoes to see over the back of whoever is blocking her entry into the circle. She listens to the gossip but is never invited to participate. If hyenas roamed the grounds of St. Pete’s, Miss Velma would be lunch.

If I haven’t exactly done my part, I have an excuse.

When I was a kid, Daddy, good old Steve Sr., dragged me to the outlands to visit an assortment of crazy old aunts and uncles. But there was one in particular, Aunt Gladys, that I’ve never been able to shake. Daddy always brought Aunt Gladys two cartons of cigarettes along with her inhaler and prescriptions for emphysema.

“It’s all she has left,” he used to say. And when I whined about going, which was every single time, he’d respond with, “We’re all she has left.”

“Can’t you just buy her an extra carton of cigarettes and leave me at home?” I’d said once. His elegant and fitting response was a backhand to the side of my head.

A kamikaze had taken Aunt Gladys’s husband, Uncle George, in World War II, leaving her with one child and a hatred for Asians that bordered on the pathological. That child, George Jr., grew up and ran his pickup into a school bus. Drunk and dead at eight o’clock on a Monday morning. With a Vietnamese hooker bloody-faced and babbling in the passenger seat.

But I didn’t care. None of that was my fault and it had nothing to do with me. Those trips terrified me.

We’d pull up the dirt drive to a tar-paper shack with a sagging porch. Aunt Gladys would shuffle to the door in a threadbare floral-print housedress and tattered open-toed slippers. She wore no stockings and the sight of her varicose-veined legs is burned onto my retinas to this day.

“Yall come in,” she’d say after unlatching the screen door, inviting us into her lair. Cats, like roaches under a light, rushed off into the other rooms, leaving only their fleas behind. Damn cats. We’d sit at the kitchen table under an exposed bulb and I’d immediately start scratching my ankles. I learned after the first time not to wear shorts, but jeans weren’t much better. I always prayed I’d get ringworm and Mama would make Daddy stop bringing me around.

While she poured coffee, Aunt Gladys would get the conversation rolling. The same one every time. Dead relatives. No shortage there. And it always ended with her damn fool son. At least George Sr. had died in battle. Why not talk about him? But no, it was always George Jr. “I just thank the Good Lord above he didn’t kill any of those kids on that bus,” she always said. Never mentioned George Jr.’s passenger, who died later at the hospital.

And the smoke. I like a cigarette now and again. But I don’t see how she didn’t die of smoke inhalation. She’d blow the first plume of each cigarette straight up into the haze hanging just below the ceiling. I’ve seen college bars with less smoke in them. For whatever reason, she never opened her windows. Perhaps she was one of those old ladies who thought the elements --- rather than three packs a day --- made a person sick. The place was always shut down tight. During the summer, it was freezing from the unit rattling away in the kitchen window. Worse was during the winter, when the wall-mounted gas heaters hissed away, backed up by two or three electric space heaters.

All things considered, it was only fitting that one cold winter night, the house blew up with Aunt Gladys in it.

“At least it was quick,” was what Daddy said.

Yeah, if you didn’t count the twenty-some-odd years of sitting alone in that kitchen, waiting to die. God have mercy on her soul.

So when I pull into Miss Velma’s dirt drive and park behind her ’70-something Toronado, I ask God for an easy afternoon, for Him to instill in me whatever spirit had moved Daddy to make those trips all those years ago.

“It’s your job,” I remind myself as I consider the squat house on its stubby concrete blocks. I know that after all is said and done, I’ll feel better for having visited, feel that inner glow of a job well done, of doing something no one else wants to do, bringing joy into another person’s life. The porch isn’t sagging at least.

A cat darts out from under Miss Velma’s car and dashes under the house.

“Christ,” I say.

“Please help me,” I add as an afterthought, but I’m not fooling either of us.

I skip the front porch and walk to the door just off the driveway. Miss Velma answers wearing a pantsuit. Not a varicose vein in sight. Her hair is combed neatly and she has a light dusting of makeup. She’s even wearing shoes.

As she holds the screen door open to let me in, an orange cat runs up the steps and into the house.

“Uh-oh,” I say.

“Aw, that’s Meenoo. I can’t keep that one out of the house,” she says with a laugh.

I step into Miss Velma’s kitchen. Bright light reflects off the recently mopped linoleum. A cigarette burns in an ashtray next to the sink, but a small fan is blowing the smoke out of the window. Meenoo rubs against a door opening onto the rest of the house and Miss Velma opens it a bit. The cat disappears into the darkness of the other side. I wonder if Miss Velma simply cleaned up the kitchen, shoved all of her mess into the other part of the house.

“I hope you don’t mind the smoke,” she says.

“Not at all,” I reply. She’s trying. “I just might join you,” I add, reaching for my pack. I don’t like to smoke in front of the flock, but it might make her feel a little more at ease.

She offers me coffee. I scratch my left ankle with my right foot out of some conditioned response. The smell of mothballs and cat food is here in the kitchen, but it’s being held at bay by candles and incense.

I notice, too, that the stove is bare. Nothing bubbling or simmering or warming. The oven knob is in the off position. Nothing in the sink and nothing in the draining board. That’s just not right.

Miss Velma hands me a cup of coffee and puts a Tupperware bowl of sugar and a jar of powdered nondairy creamer on the table. Coffee is good. I like coffee. But I swear she’d said lunch. My stomach growls as if in agreement.

I say nothing about the apparent lack of food and sip my coffee. We start talking and it isn’t long before her story comes spinning out. Born and raised on a Grand Prairie farm, married young to a good man, a farmer who later became a bus driver for the St. Landry Parish school district. They had no children, something wrong with one or both of them. They never bothered to look into it. It was a different time then --- just after the last of the orphan trains rolled through south Louisiana and before fertility treatments were as common as cold remedies. If you were barren, you lived with it until God sent down an angel to change you, perhaps striking your husband dumb in the process. Still, they were happy with each other, one of those couples that could have lived forever without the rest of the world and been happy as clams.

Mr. Richard died ten years ago.

“He had a heart attack,” she says, blowing out a cloud of smoke. “Right there in bed. It was bad, bad, Father. Thirty-five years I was married to that man and I never seen a look like that on his face. Never seen him cry.”

“It must have been hard on you,” I say, reaching over and patting the back of her hand. The move surprises me. I’m not the touchy-feely type, but it strikes me as the right thing to do. It’s what priests do in the movies.

She stares down at my hand on top of hers.

“You get used to a person after that long. And then they’re gone. You know?”

I don’t. I absolutely don’t. I live behind a church, by myself. I don’t even have a dog. I’ve only been alive thirty-two years.

But I need to say something. That much is obvious. In the space of seconds, Miss Velma has seemed to shrink. Her shoulders are slightly hunched now and I swear the room gets dim, the smoke starts to collect around us, the old smell of defeat gets stronger.

“I’ll tell you what. I’ll remember you both in my prayers tonight. And I’ll light a candle for Mr. Richard over at the church.”

It shouldn’t be that simple, but it is.

“Thank you, Father Sibille,” she says. “That’s so nice of you.” And her smile comes back. It’s a little weaker, sure, but a couple of kind words from the priest and it was all a little more bearable.

She pats my hand now, stands up, and goes to the fridge.

“I don’t cook too much since he’s gone, but I still like to make chicken salad. That was his favorite.”

“That sounds great,” I say. And I mean it. It’s not just that I like chicken salad --- and I do --- but the thought of a light lunch, something cold served on white bread, is somehow liberating. The conversation was heavy enough.

Miss Velma places the large ceramic bowl on the table. The chicken’s been shredded down almost to a paste, just the way I like it. She grabs two plates and a loaf of Evangeline Maid bread and is making the first sandwich when someone knocks on the door.

“Miss Velma, what you doing in there, girl?”

“Oh, it’s Vicky,” Miss Velma says. But I’d recognized the voice immediately.

“Well, that’s nice,” is all I can think to say.

“Come in, come in,” Miss Velma says.

“Hey, folks. Hey, Padre, thought I saw your car out there. Figured I’d stop in and see what kind of party I was missing.”

Miss Velma giggles. “Father Sibille, Vicky stops by all the time to say hi,” she says with a hint of pride.

“Really?” Well, there goes my beatification, I guess.

“We’re just having some lunch, Vick, so you gonna have to stay and eat you a little something,” she says, grabbing another plate from the cabinet.

“Okay, but only if you sit down,” Vicky says, pulling a chair from under the table and motioning to Miss Velma, who doesn’t put up an argument.

With that, Vicky takes over, makes two sandwiches for each of us, fetches a pitcher of iced tea from the refrigerator, and lunch is on. Smiles all around. It’s that simple.

Following lunch, Miss Velma and I are enjoying a post-meal smoke and Vicky is washing dishes when she suddenly says, “Little Red Riding Redneck!”

I practically fall out of my chair. “What?”

“A little girl in a red hoodie just rode by on her bike,” she says. “Red jacket and long skirt. Weirdest thing. I’ve never seen her around here before.”

“Which way was she going?” I ask, already at the door.

“Toward Ville Platte,” she says. “Steve, what’s the matter with you?”

“Bye, yall,” I shout, and offer no further explanation before running out to the car and nosing it onto the road heading toward Ville Platte. I’m not even a mile down the road when I see her ahead of me, steering her bike with one hand and swinging a stick at the tall grass growing from the ditch running along the shoulder. I drive by at forty miles per hour and glance at her through the rearview mirror. She looks like a normal kid riding her bike on the side of the road. A ghost, she’s not. But Pentecostal she does appear to be.

The long hair tied up in a bun. The ridiculously impractical denim skirt. Where the hell did she come from? I didn’t think there were many --- or any, for that matter --- Pentecostals back here.

I keep on driving. I never come down in this direction. All of my house calls so far have been in Grand Prairie proper (as loosely as that’s defined) or on the road toward Washington. I slow down to thirty and keep an eye out for a house or gravel road heading off into the woods that could conceivably harbor a nine-year-old Pentecostal girl.

I’m about to turn back after four miles when I see in the distance a large yellow bulldozer worrying a mountain of dirt off the side of a newly laid gravel road in a recently cleared field. A handful of trees --- four stately oaks and three pecan trees --- have been allowed to live. The trunks of the fallen --- those that haven’t been hauled off yet --- are stacked neatly on timber-hauling beds waiting only for the trucks to come and cart them away. Toward the back of what appears to be a twenty-acre piece of land are the burning remains of pulled stumps.

Sitting under the biggest oak is a double-wide trailer. In front of it are a wine-colored Cadillac, a brand-new Chevy Suburban, and a child’s jungle gym. Swinging from the monkey bars is a small, pale redheaded boy.

“What is this all about?” I ask myself.

I’m not exactly proud to admit it, but Pentecostals bug me. Unlike Baptists and Methodists or any other Protestant faith, they simply strike me as traitors. Why? Because my perception, right or wrong, is that many of them --- the ones in south Louisiana, at any rate --- were born and raised Catholic and then, one day, they turned tail and ran.

And they took Timmy with them.

Timmy was my best friend in grade school. Before he suddenly changed. Kindergarten through fifth grade we were as thick as thieves. Then one year, he was a week late coming back from Christmas vacation. When he did come back, he told me bluntly: “We ain’t Catholics no more. Mama and Daddy switched us to Pentecostal and they say the rest of yall are going to burn in the fires of hell.”

How’s that for a conversation starter? The details at the time were fuzzy. His parents had converted and adopted a whole slew of weird rules. Out went the TV. Out went the movies. Out went any music other than approved Christian stuff. No more cursing. In other words, out went everything twentieth-century American kids based their friendships on. Hell, Timmy couldn’t wear shorts anymore. His sister and mother couldn’t cut their hair or wear makeup. On top of that, he had to go to church twice during the week and another two times on Sunday.

Even more mystifying was that he seemed happy about all of this. How could he be? Everything enjoyable in life had been taken from him. Worse, as the weeks went by, as he grew into his new religion and learned its language, he started talking about the Holy Ghost more and informing me that I was going to hell for listening to Eddie Rabbitt’s “I Love a Rainy Night.” When we went to Mass once a week for school, he’d sit there and watch the priest intently as if expecting him to burst into flames.

“He’s the one who’s really gonna get it,” he’d tell me.

“God, Timmy. Shut up!” I remember telling him one day. “Why do you even come to this school anymore if you’re so full up on Holy Ghost? Why don’t you go talk in tongues somewhere?”

My words didn’t seem to make an impact. “Because it’s halfway through the school year, that’s why. Once summer rolls around, I ain’t ever coming back to this school and I’m never going back into one of those churches. All them false idols drive me crazy.”

“False idols? What are you even talking about?” I wanted to know.

“Statues and stuff, dummy. All them saint statues ain’t any better than a golden bull.”

And that was pretty much the end of it. We tolerated each other until the end of the school year, and I spent more and more time with other friends talking about Transformers and Smurfette and whether country music was even worth listening to. And at the end of the school year, Timmy bid us all good-bye and we never really saw him again.

Of course, with half a lifetime under my belt and a library of gossip at my disposal, Timmy’s happiness at the time isn’t such a mystery anymore. His parents hit a rough patch when the oil market went under in the ’80s. Daddy started drinking. Mommy started yelling. They both started smacking Timmy around. Then one day they realized they needed help or someone was going to get really hurt. Their twice-a-year Catholicism really didn’t do much for them. They probably felt they’d have the eyes of the whole parish on them if they started going to church more often. “There’s the drunk and his beat-up wife,” they’d whisper. A friend of a friend told them about this new church, which just happened to be filled with rules --- no drinking, for exam- ple --- and structure and a whole community of people trying to get their acts together.

As far as Timmy knew, Daddy caught the Holy Ghost and he quit being a mean old drunk. Now, those are results. And it was certainly more than all those statues in the big brick and marble building had ever done for him.

Good for Timmy. And good for the Pentecostals.

Still, they took my friend away from me, the bastards.

And now they seem to be setting up in my backyard. Across the gravel road from the big trailer under the oak tree where the little boy is playing, there are four more --- all double-wides by the looks of them --- set at fifty-yard intervals from one another. Each trailer is on its own concrete slab. On the right side of the path, groups of men are knocking together wooden braces where I assume more slabs will go. Clusters of gas and water pipes sprout from the dirt like wildflowers telling me it’s just a matter of days before the new slabs are poured and more trailers moved in.

How does this happen? There’s a suburb going up back here without me knowing about it?

The bulldozer comes to a jerking halt and the driver climbs out of the cab and stands on the passenger-side tread of the machine. While he considers my car, he pulls a red bandana out of the bib of his denim overalls and wipes his brow. Like meerkats who’ve detected a hawk, the men working on the slab frames for the trailers all pop their heads up, look to the stopped bulldozer, look at my car, and settle their eyes on the bulldozer man. He waves his bandana at them absently and they go back to their work.

He then flicks a wave my way in hello and motions me over. I ease up on the brake and inch down the drive, watching him the whole way.

I stop the car and walk across the fresh dirt of the field. I feel it sticking to my shoes, but don’t look down. I don’t want to come off as prissy.

This guy’s a mountain of a man, central casting’s idea of a Midwestern farmer: barrel-chested, beer-bellied (though if he’s Pentecostal, he doesn’t drink), a long-sleeve plaid Western shirt poking out from his overalls and wisps of blond hair sneaking out from under his camouflage baseball cap. The cap is the kind with the mesh back, the kind worn ironically by cool kids in big cities. But irony isn’t in this man’s vocabulary.

He’s probably well on the other side of fifty, but despite his age and his size, he hops spryly from the tread of the bulldozer and meets me halfway, offering his hand as he approaches.

“How you doing?” I say.

“Hoo-boy, I tell you. If things got any better, it just might kill me,” he answers in a twang much more traditional Southern than the local Cajun. His eyes practically twinkle. He gives my hand a vigorous shake. “I’m Reverend Paul Tomkins,” he says.

“Reverend? Is that right?” I say, smiling like an idiot.

“Well, soon to be. Once this here church is finished.” He waves his hat back at the bulldozer and mound of dirt behind him as if it’s all just some little task to finish in an afternoon, like cleaning the attic or emptying out the garage. “But you can just call me B.P. Brother Paul. That’s what the brothers and sisters back in Church Point called me.”

“Is that so?” I respond.

“Yup,” he says, casting an eye out over the property and hooking his thumbs into his belt loops. “Oh, shoot,” he says. “I’m plumb forgettin’ my manners today. I didn’t even ask your name.”

Now it’s my turn. “Father Steven Sibille. From St. Peter’s just up the road in Grand Prairie. Everybody just calls me Father Steve.”

The smile remains fixed on his face but something changes in his eyes. He’s examining me now. I’ve gone from a potential member of his flock to some sort of alien species.

“Is that right?” he says. He looks over at the men working farther back in the field, as if I might run back there and snatch their souls. He turns back to me just as quickly and asks, “Where’s your uniform at?” The joke seems to put him back in his good mood.

I force a chuckle. “I left it back at the church.”

“Afraid to get a little dirt on it?” he asks.

What’s that supposed to mean? I look at him. I can’t tell if he’s joking or if he’s making a statement about the Church. “All that black gets a little hot,” I respond. “Besides, I find it makes introductions a little stiff, makes people a little nervous.”

“Yeah, funny how that works,” he says. He’s still smiling at me. I wonder suddenly if he was born Pentecostal or if he’s an ex-Catholic with an ax to grind. I smile right back at him.

“Anyway,” I say, trying to brush off his comment, “I don’t make my way out here that often, but I saw your daughter in the woods behind my house the other day and didn’t know quite where she’d come from.”

Storm clouds gather in his eyes and suddenly I regret ratting on the child. She’ll probably catch a beating tonight. Corporal punishment is one of the few things not forbidden by the faith. Spare the rod, spoil the child, and all that. But his eyes clear up and the smile’s back on his face. “Oh, Cindy-bell? She ain’t nothin’ but a goat sometimes. I swear, that girl will wander all the way to Baton Rouge one day if we don’t keep an eye on her. I hope she wasn’t botherin’ you none.”

“Oh no. Absolutely not. She just ran off. I think I might have scared her.” I’m starting to realize just how ridiculous this might sound. “And I saw her head out this way, so I followed.” Ridiculous or dirty. “So I drove out here to…” To what exactly? “To, um, make sure there was somewhere she was running back to.”

“Is that right?” he asks, not really expecting an answer. “Just so you know, you don’t have to worry about her. She’ll always find her way back home no matter how far she wanders. But I can tell her to stay away from there if you want me to.”

“No, not a problem at all. She’ll just want to watch out in them woods with squirrel season going.”

A real smile comes back to his face. “Heck, Father. I’d bet that’s what she’s doing back there. Practicing.”

“Is that so?”

“I’ve been taking that girl hunting with me since she was knee-high to a grasshopper. And this is the first year I’ll let her use her own gun. Her mama ain’t too happy with me. But it was pretty much the only way I could get her to move from her little friends in Church Point without her pitchin’ a fit and hatin’ me for the next six months.” He shakes his head. “But that’s family for you,” he adds.

“Yeah, that’s family for you,” I say, as if I have any clue at all what he’s talking about. Family. So I try to change the subject. “Pretty impressive progress you’re making out here.”

“You ever hear of the Amish, Father?”

“Certainly. I went to seminary up in that part of the country.”

“Ever seen them throw up a barn?”

“Yeah, pretty impressive stuff,” I say. In fact, I’d done just that one day. A Catholic farmer down the road from the seminary told us he’d hired a crew of Amish to build a stable and he invited us over to watch. We woke up at dawn and drove down to the site to find them already working. Sunup to sundown with a half hour for lunch. Hammers pounding all day. It was exhausting just watching them.

“I like to tell people we’re just as good as the Amish, but twice as fast because we use power tools.”

“Well, it definitely isn’t a union schedule,” I add.

We both laugh, and I hope we’re done trying to one-up each other. I don’t know if I can compete.

“So what are you planning out here?” I ask. “You building a trailer park?”

“Certainly looks like that, don’t it? Just family, though. Me and Christine in that trailer, there. My oldest son and his wife and baby in the next one. My sister and her family in the next.

And her oldest son and his wife in the next. On this side of the street, it’s going to be Christine’s family.”

“Wow. That’s a lot of family,” I say, impressed and maybe even a little jealous.

“Certainly is. We drive each other crazy every now and then, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

“I bet,” I say, but really I have no frame of reference for the things coming out of his mouth.

“That’s my boy and some of his cousins getting the slabs ready. And I’m just leveling ground for the church. Once everyone’s set up and comfortable, we’ll get rocking on that.”

“And the church?” I might as well get all the bad news at once.

“Nothing too big or fancy,” he says. I see the twinkle back in his eyes and I know what he’s going to say next. “Just a little bit bigger than yours, I guess,” he says, and gives me a light punch on the shoulder.

I’m sure his laugh is much more sincere than mine. And who is this guy to be touching me, ten minutes after meeting me?

“But seriously? About enough room for six hundred people.”

Six hundred people? I whistle. I can’t help it. That’s a lot of people. A lot of Pentecostals at any rate. I try running my own numbers. I know what the books say. Of the 500 people known to be living in Grand Prairie, I have 475 either baptized or confirmed at St. Pete’s. The church only holds 250. Not all of the 475 --- not even close --- actually go to Mass, and those that do are spread out over the three services. A Pentecostal church, of course, would have to be big enough to hold them all at one time because the services are all mandatory. But still.

“Wow. Six hundred. Pardon me for asking, but are there that many Pentecostals back here?”

“Not yet,” he says, again offering one of those half-joke, half- gibe responses. “Got quite a few on this end of Ville Platte. An other handful creeping out on the north end of Opelousas, near Washington.” He pauses. “Got some others from Church Point and Melville buying up some property in these parts.”

“Is that right?” I ask.

“That’s what I hear,” he says. “Don’t know if that’ll make six hundred. But I’m an optimist.”

“Best thing to be,” I say, hardly meaning it. I’ve got a parish full of old people. I’m afraid I’d lose half of it if a flu epidemic swept through.

“After that,” he adds, “you never know who’ll walk through the door.”

And that remark, I know, isn’t a joke at all. They took Timmy. They’ll take more.

Chapter 3

I head over to Easy Time to let Miss Rita have a go at me. Of course, that means I have to bring offerings. Whatever Jesus may have thought about pork, Miss Rita is a big fan of the pig and all of its parts. “Everything but the oink,” is her summation of the edible nature of the animal. “I’d eat that, too, if they found a way to cook it.”

Sadly, the only pork that finds its way onto the menu at Easy Time Nursing Home are the tiny flecks of pink they sprinkle into the split-pea soup. In her first years at Easy Time, Daddy would sneak in pork every once in a while. The baton then fell to me. When I went off to seminary, it fell to Teddy, Miss Rita’s favorite grandson. But Teddy was sloppy and got busted by the attendees at the front desk.

Happily, Miss Rita has found another supplier. One who takes the time to double-wrap the pork --- once in foil, once in plastic. One who then puts the now less-odiferous offering into a sealable plastic container, which then goes into that official-looking black leather satchel of mine.

The white collar helps as well.

I walk past the front desk, which has now sprouted a crop of little Christmas trees, and offer today’s receptionist --- a humorless Nurse Ratched sort --- my best smile. She waves me on.

I stop outside Miss Rita’s door and put my ear to it. I can hear her cackling with laughter to some comedian on television doing a bit about the difference between black people and niggers --- a favorite topic of hers.

In the time it takes me to push the door open, she’s dropped her chin to her chest and gone into one of her fake stupors. Today she’s wearing a shirt that reads Hi Hater. I don’t know what it means and I’m certainly not going to ask.

“It’s just me,” I say. “And I still don’t understand why you do that.”

“ ’Cause if it’s one of them attendees, I don’t feel like them walking in here then wanting to talk to me. I figure if they gonna treat me like a baby half the time, I might as well act like one. Besides, bad enough I have to entertain you today.”

“Go on,” I say. “You keep that up and I’m not going to share.”

She locks her eyes on me. “Don’t even play around with me, boy. I might have one leg, but one’s enough to kick your ass.”

I never get tired of that line. It gets a chuckle out of me every time.

“Yeah, go ahead and laugh,” she says, smiling now, her eyes bright with anticipation. As I reach into my bag, she wheels over to her secret stash and produces her bottle of Crown Royal. “Getting low,” she says. “Don’t forget next time.”

“What about Teddy?” I ask as I remove the hunk of pork shoulder from the container, then peel the wrapping from the pork roast.

“Teddy? Ha! Teddy don’t drink. Doesn’t approve of it. Don’t know where he picked that up. That boy’s lucky he’s family because otherwise I wouldn’t let his little butt in here.”

The pork, tender enough to break apart with a plastic spork, is still warm. I put it on a paper plate, then produce two smaller plastic containers, one full of rice and gravy, the other full of black-eyed peas with chunks of real bacon.

“Oh my, oh my, oh my,” she says, fanning her face. Her eyes well up with tears. “You know what they fed me last night? Steamed chicken with steamed broccoli. Chicken breast!” She spits the words out as if they were bits of the offending food. “White meat!”

I get the food plated, put the plate on a tray, and just as I’m sliding the tray onto the arms of Miss Rita’s wheelchair, the door pops open. I freeze. Miss Rita, who’s just raised the bottle of Crown Royal to her lips, freezes as well, her eyes grown big for a split second. But just as quickly, she swallows the whiskey, wipes her mouth, and hisses.

“Timeka, get in here and close that door, girl.”

I stand slowly and turn around to find a petite black woman --- she might be five feet tall if she wore heels --- dressed in the white uniform of the attendees. Great.

“Miss Rita!” she stage-whispers. “And, Father. Shame on you! Getting this old lady drunk.”

“Don’t pay her any mind, Steve,” Miss Rita says. “She just came in here to snoop.” But her usually blustery tone slips a little. “You not gonna tell on me, are you?” she asks, suddenly serious.

“I should,” Timeka says, looking at me. “But I don’t like that old cow supervising today. Besides, you made it this far in life. I don’t see how it’s going to matter now what you eat and drink.”

“Amen to that,” Miss Rita says, raising the bottle and taking a swig. “Steve, this Timeka. Timeka, this Steve.”

I offer my hand. Hers is cool and dry and small in mine. “Hi.” She pauses. “Father.”

“Nice to meet you,” I say, casting a glance at Miss Rita, who’s watching us both intently.

“Well, I best be seeing about my rounds,” Timeka says, and just as quickly as she’d come, she’s gone.

As the door closes shut, Miss Rita suddenly becomes very fascinated with her food and won’t look up. Still, I can see the prankster’s smile reaching up to grab her ears.

“Really, Miss Rita. You have to give up this foolishness about me getting a woman.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she says. But without looking up she adds, “But I hear she has a thing for white boys. Especially ones in uniform.”

“Just stop it. You’re wasting your time.”

“All’s I got is time,” she says. “Might as well use it to help you.”

“I appreciate it, but I don’t need your help.”

“No, you need a woman.”

I look at her. She looks at me. It’s been playful so far, but she’s gauging me to see if she can keep pushing it.

“Forget you,” she says, finally. “Just keep bringing me my little presents and I’ll quit meddling.”

“That’s so nice of you, Miss Rita,” I say. “But we both know that’s not true.”

She looks up at me, somehow managing to smile while gumming a huge mouthful of pork. She swallows and points at me with the spork. “You right about that. But do us both a favor, boy.”

“What’s that?”

“Hang around some people your own age. All this time with little old ladies? The rest of it sitting alone out there in the woods? That can’t be good for you.”

“That’s the path I’ve chosen for myself.”

“Well, you better find another one before you end up someplace bad. I’m telling you, go find some friends your own age,” she says. “Now, let me eat my food in peace,” she adds before turning her full attention to the pork.

“Wonder what them little old white ladies would think, they knew their prize pork roast was going to some old negress?” she says to signal that she’s done and ready to get back to minding my business.

“I’m sure my parishioners wouldn’t mind at all. There’s not a racist bone between them.”

“Yeah? Ain’t that nice? How many black people yall got back there in Grand Prairie?”

I don’t say anything.

“How many they got in Opelousas? About ten thousand? And in little tiny Plaisance? About six hundred-fifty out of the seven hundred people live there? And Grand Prairie? Not a damn one. Boy, I live around here a lot longer than you. Don’t be fooled just because it looks hunky-dory back there now.”

“Miss Rita ---” I start, but she cuts me off.

“Don’t Miss Rita, me. Tell me something. They still got that man back there? He’d be pretty old by now. But he spends most of his time hunting squirrel in the woods.”

“That describes about half the old men in Grand Prairie.”

“Oh, I know that. But come on, boy. You smart. Think about their names. There’s one of those names that sticks out.”

Part of me wonders how she could possibly know any of the old coots back there, but I start listing out the names in my head. Earl Vidrine. Butch Lafleur. Lem Landry. T-Chew Vidrine. Harold Fontenot. Poot-poot Arcenaux. Then I have it.

“Noose?”

“Funny name, huh?”

“I’m sure it’s just a name, Miss Rita.”

“Yeah? How you sure? That’s an odd name just to get. And certainly no mama’s going to name her baby that, even if she’s in the Klan.”

Noose? The one or two times I’ve talked to him, he seemed like a nice quiet old man.

“They mighta drawn up their truce a long time ago,” she says, “but if black people staying out of a town, there’s always a reason for it. Might be safe now. And I’m sure confession ain’t exciting as it used to be, but black people are scared of ghosts.”

“Should I even ask about anything else?”

“Not if you want to look those people in the eyes every Sunday.” She pauses. “But I’ll eat their food anyway. They still know how to cook.”

I think she might even get more pleasure out of it knowing that it was prepared by an old white woman who’s never had a black foot step across her threshold.

“So,” she says after taking a nip from her Crown Royal bottle. “What about that old priest’s little girl? She should be about your age.”

“How do you know about Vicky?” I ask.

“Steve, everybody but the pope knew about that child. Vicky, huh? That her name? Nice name. She pretty?”

“Stop it.”

“You didn’t answer my question.”

“Yeah. Sure. She’s pretty. You happy?”

“Be a lot happier if y’all start… well… you know.”

“Oh, dear Lord,” I say in exasperation.

“Boy, you know you’re not supposed to talk like that.”

“It’d be a lot easier if I didn’t have you driving me crazy all the time.”

“Hmmph,” she says. “Seems to me if you don’t want to be driven crazy, you could find someplace else to go hang out.”

“Believe it or not, you’re not the only thing driving me crazy, Miss Rita,” I say.

“Oh yeah? That Vicky girl getting after you?”

This time I just stare at her, refusing to say anything.

“Fine, then! Deny an old lady her dreams. Now go on. Tell me what’s the matter this time.”

I tell her about Brother Paul and the Pentecostal invaders, that I’m worried about him coming after my flock.

“I heard about that man.”

“You have?”

“Oh yeah. They talking about him all over town. He start out as Baptist, but kept butting heads with people that run that show. So he jumped to Pentecostal.”

“So he’s not all that great,” I say.