Excerpt

Excerpt

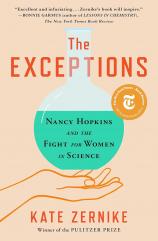

The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

Chapter 1

An Epiphany on Divinity Avenue

It was hard to deny the promise.

It was the second Tuesday in April 1963. Midmorning sunshine splashed the campus of Harvard University, where the trees were budding, and students were just back from a weeklong midsemester break. A Harvard man was in the White House, the youngest man ever elected president of the United States, heralding the dawn of a New Frontier. And here in Cambridge the next generation of ambitious young minds set out in crisp air along the tree-lined paths of the nation’s oldest university, any of them on the way to do—it could be me—the next big thing.

At eleven o’clock, just north of the wrought-iron gates of Harvard Yard, and just east of the grounds where George Washington had once assumed control of the Continental Army, some 225 undergraduates, many in jackets and ties, filed down the gentle slope of a lecture hall to hear from a professor leading a revolution for the twentieth century. Five months earlier, James Dewey Watson had been in Stockholm with Francis Crick to collect a Nobel Prize for decoding, at age twenty-four, the structure of DNA, a discovery he called, immodestly but not incorrectly, “the secret of life.” Watson and Crick’s double helix had immediately placed them in the pantheon with Darwin and Mendel for explaining the development of life on earth and sounded a starting gun in the high-stakes race of modern genetics.

Now tenured at Harvard, Watson was about to begin his series of lectures in the introductory biology course for undergraduates. A tutor had written him that the students had done “rather well” on an hour-long test just before break: “They will return to Cambridge full of seasonal and customary liveliness and anticipating meeting you.”

Nancy Doe, a junior, was already seated in the second row of the center section, almost directly in front of the lectern. She had arrived early, against her norm, and chosen her seat carefully. Not in the front row, because she didn’t want her classmates to think she was a celebrity hound, and not in the back, where she usually hid, because she had read in the student evaluations that Watson dropped his voice at the end of his sentences, and she wanted to hear every word. Tall and slender, she had a sprite-like smile and wide blue eyes that took in everything but gave little clue to what she made of it. Her expression could shift from excited and girlish to wary and jaded in an adolescent minute. She nearly itched with intensity, considered her thick dark hair impossible to manage, her legs in their black wool tights absurdly long. Her mind tended to race, restless until it could alight on the biggest problem she could find, which at that moment was what she was going to do with her life. At nineteen, her future lay wide-open in front of her, but sitting in the wooden fold-down desk, she felt nothing as much as time closing in. Her father had died the previous year, and neither her wide circle of friends, the prerogatives of an Ivy League education, nor her tall, handsome boyfriend had insulated her from mounting dread.

Watson appeared suddenly, as if by a tailwind in a cartoon. Nancy sat up to look. This could not be him, she thought. He looked no more than thirty—in fact, he had turned thirty-five on Saturday, still young for a professor, much less a Nobel laureate. He was well over six feet tall but still gangly like a teenager, with enormous ears, a long bony nose, and round, protruding eyes. His hair was receding and barely tamed, a disobedient squiggle airborne over his forehead, like Tintin. He radiated impatient energy, his eyes everywhere at once—on his notes, on the students filling the room—looking through more than at. Watching, Nancy thought of him as a winged messenger, a wizard in a J. Press suit stopped in the middle of some monumental discovery to deliver the word to these lucky Harvard undergraduates.

Watson was cultivating a reputation as a showman, and he began grandly: What is life? Life, he told the students, came down to one molecule, DNA, which was in every cell of the body. It was made up of four bases, always in two complementary pairs that fit together in sequence, like the teeth of a zipper, to create genes. In those bases was all the information needed to create a living organism. Tear apart the zipper and DNA gave you a template to create an exact copy, the next generation. It was life, and the ability to start a new one.

Nancy had come to class understanding little about the double helix or DNA, little more than that a Nobel Prize was a big deal. From what she had read, she expected that Watson was going to deliver a master plan to explain human biology.

But as he spoke, she realized that Watson knew the answers to the questions that had been preoccupying her over the last year, or at least where to find them. If DNA was in every cell, everything there is to understand about humans must be written in there somehow: not just the color of their eyes, but cancer, and even how they behaved. Watson and the new cadre of molecular biologists were going to be able to figure it all out: a dumb gene, a smart gene, a fat gene, a thin gene, a nice gene, a nasty gene.

Watson was conversational, funny, prided himself on being the liveliest of the four lecturers in Bio 2. His voice was indeed quiet, but his tone was imperative, and she began to feel as though he were speaking directly to her.

It would all become more complicated—the science, Watson—much, much more complicated. But in that moment, the idea that life could be reduced to this one set of rules comforted and thrilled her. The promise of it drowned out everything else: the pressure of the hard wooden seat against her tailbone, the grief over her father, the worries about her widowed mother and her own future.

At the end of the hour, Nancy floated out of the classroom building to join the noontime stream of students emptying out of lecture halls onto Divinity Avenue. They passed hulking Memorial Hall and crossed Kirkland Street and Broadway, oblivious to the four lanes of traffic waiting for them to pass, then funneled through the ornate gates to disperse onto the diagonal paths of Harvard Yard. Normally, on a sunny day like this, rather than walk back to the Radcliffe dining hall, she would meet her boyfriend, Brooke, on the other side of the Yard. They’d grab the special at Elsie’s Sandwich Shop—roast beef with Russian dressing on a roll—and join the other young couples on the grassy banks of the Charles. But on this day, she wanted to be alone with her thoughts, to give her brain time to absorb what it had just heard. She took her time, avoided eye contact. She did not want anything to break the spell.

All year Nancy had been casting about for what to do with her life. She was adamant that it be something serious and meaningful, but she had little idea what that would be, beyond a diffuse desire to reduce human suffering. She imagined she would get married and have children—few young women her age would do otherwise—and she knew that she had to do so before she turned thirty, after which childbirth was thought to be dangerous. That gave her ten years to accomplish the professional goals she had not yet determined, and now, a year to figure out what those goals might be. Otherwise, she feared, she would too easily slide from graduation to marriage, a dog, children, the suburbs. A fate she thought of as a kind of death by privilege.

She had grown up in a rent-controlled apartment on 120th Street and Morningside Drive in New York City, in a building owned by Columbia University. Her mother had gone to Teachers College there and taught art in the city’s public schools, and Nancy’s father was a librarian at the New York Public Library. She had a sister, Ann, who was eighteen months older. Their maternal grandmother, who had emigrated from England, lived in the same building; from her Nancy acquired a slight accent that would for her whole life flummox people trying to put a finger on her background.

Since kindergarten she and Ann had been scholarship students at Spence, the elite girls’ school on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, both of them in the thick of the small class of girls in their years. Spence instilled in its girls an understanding that they were privileged, and that with privilege came responsibility. They were cultivated to do important things, to go on to Seven Sisters colleges and be the best students there, to be leaders, though leaders of a certain kind: in the Junior League, or charity work. And they should be well mannered in their pursuits: the school taught its girls never to chew gum on the bus or speak loudly in public, to defer to elders and to not boast. Arriving at school each morning, they curtsied to a uniformed doorman, which their teachers told them was good training should they ever be presented at court to the queen.

Both Nancy and Ann were known as exceptionally bright, especially Nancy. She could hear a song on the radio and immediately play it on the piano; when the woman who played at morning assembly at Spence quit, Nancy took over. She had little interest in reading, but loved math, saw a beautiful language in its order. She thought of it like eating candy: a sweet burst of pleasure in solving each problem. The telephones in their building at 106 Morningside Drive ran through a plug-in switchboard, and the operator who worked it once complained to Ann that she’d taken thirty messages from Spence girls looking for Nancy’s help with the night’s math homework.

Nancy’s experience at Spence also taught her not to put too much value on money. Her school friends with their governesses and duplexes on Fifth Avenue wanted their playdates to be at Nancy’s house, where her mother would be on the floor making papier-mâché dolls from spent light bulbs. It seemed to Nancy that her classmates’ parents were out every night—she read about them in the society pages of the New York Times—and always getting divorced. She and Ann called their parents by their first names, which evolved into made-up terms of endearment, and even their classmates called Nancy’s mother Budgie and her father Diegles. Proper Manhattan never strayed north of Ninety-Sixth Street, but to Nancy, her neighborhood was like a small town in the city; she and Ann trick-or-treated between apartments in their building, played on the deep sidewalk that faced Morningside Park. At Easter they went to watch the parade of hats and finery along Fifth Avenue, inventing a game to see who could pat more mink stoles. On weekends, Budgie led the family on adventures around the city: to the medieval Cloisters, or the Museum of Modern Art, where Nancy was entranced by the Kandinsky. She recalled her childhood as unusually happy, rich, not in money but in education and family.

Still, she fixated early on particular anxieties. The radio played often in the apartment, and from a young age Nancy had heard news reports about the aftermath of World War II, the emaciated and orphaned children returning home from concentration camps, a little boy who’d had his eyes poked out by Stalin’s guards for the sin of putting flowers on his father’s grave. How could humans act so cruelly? The Cold War air raid drills at school, sending Nancy and her classmates diving under their desks for cover, made her think these terrors could come right to her in New York City. She worried about losing her tight-knit family, couldn’t imagine life if any of them died. Her father had had rheumatic fever as a child, which left him with a weak heart. When Nancy was ten, her mother had skin cancer—doctors cured it, but Nancy knew from the way her mother whispered the word that it was reason to be fearful.

Her father was quiet, New England in his ways. His grandfather had been a distinguished chief justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court and his legacy dominated the family lore. Justice Charles Cogswell Doe had been an eccentric—he kept the courtroom windows open in the winter and insisted that his four children wear only navy blue. But he had a reputation for granite integrity. From his example, which Budgie summoned regularly, Nancy understood that the worst thing you could do was tell a lie. When the calls seeking help with math homework became too frequent, she decided it would be faster if she just did the homework problems for her classmates on the chalkboard at school. When the teacher got wind of this and confronted her, Nancy replied that she had done no such thing. But she couldn’t sleep that night and returned to school the next morning to confess.

Budgie was the more outgoing parent, the driver of her girls’ efforts and success. She had impressed upon Nancy and Ann the need for women to make an independent living, though she also told them that having children was the most satisfying thing they could do. She herself had grown up hearing the story of her grandmother who had been left widowed with eight children and impoverished after her husband, a doctor in rural England, fell from his horse returning from a house call. Budgie recalled the despair of the Great Depression, seeing people jump from windows after losing their savings and jobs. She had given up her ambitions to be a painter when she realized that she could not make a living as an artist. She had a first-generation American’s faith in the transformative power of education and had early on decided that the girls should go to Harvard and that the best way to get to Harvard was through Spence.

Ann had gone off to Cambridge first. Nancy skipped tenth grade—Budgie worried she’d be languishing at home—and followed the next year, in September 1960.

Of course, the Doe girls could not be Harvard students; they were admitted to Radcliffe, which had been founded in 1879 after Harvard rebuffed women’s repeated attempts to apply. “The world knows next to nothing about the natural mental capacities of the female sex,” Harvard’s president Charles Eliot declared in his inaugural address in 1869. “Only after generations of civil freedom and social equality will it be possible to obtain the data necessary for an adequate discussion of women’s natural tendencies, tastes, and capabilities.”

Radcliffe started as an experiment, dreamed up largely by daughters and wives of Harvard professors, to educate young women “with the taste and ability for higher lines of study.” For decades, Radcliffe students relied on Harvard professors who were willing or interested enough in the extra paycheck to cross Massachusetts Avenue to teach women in separate classrooms around Radcliffe Yard. Harvard allowed ’Cliffies into its lecture halls only during World War II, when the number of young men going off to war put the university at risk of losing tuition dollars. This arrangement of “joint instruction” continued throughout the twentieth century. And during Nancy’s years in the early 1960s, everyone, from the presidents of both institutions to the Radcliffe alumnae to the Harvard Undergraduate Council, still agreed that full integration would be a step too far. By quota, Radcliffe was allowed to admit one girl, as they were still called, for every four men of Harvard. It was an exclusive set; while Radcliffe graduated more Black women than the other colleges of the Seven Sisters, there were still only two or three in a class of roughly three hundred each year. There were none in Nancy’s class.

The president of Harvard, Nathan M. Pusey, was the first since the founding of Radcliffe to have a daughter but showed relatively little interest in the education of women; he declined to attend the dedication of a new graduate center at Radcliffe in 1956, noting in his papers that it conflicted with the Harvard-Penn football game. In speeches and reports Harvard officials referred to the university as “she” with the reverence one would a goddess or an ocean liner. Actual women had to enter the Faculty Club through the back door and eat in a separate dining room. They were not allowed in the main library, or Harvard’s undergraduate dining halls except as someone’s date (the Harvard man had to pay for her meal). For the most part, Radcliffe girls aligned with the expectation that they be the ornamental sex: “We know that beauty is only skin deep, but you don’t have to look as though you lived only for things of the mind,” a Radcliffe student handbook from the 1950s tsked, explaining the rules against pants downstairs in the dormitories.

Those rules persisted through Nancy’s time at Radcliffe. But the institution had begun to rethink women’s education, starting with the arrival of Mary Ingraham Bunting, a microbiologist who in 1960 became Radcliffe’s fifth president and its first with a PhD.

Bunting, known since childhood as Polly, quickly saw that Radcliffe women could not help but feel like second-class citizens. Life in their dormitories was “detached and thin” compared to Harvard’s house system, with its live-in tutors, guest speakers, and bounty of student activities. Bunting began publicly decrying what she called the “climate of unexpectation” for American girls, steered away from education and into early marriage by “hidden dissuaders,” “the inherited influences, the cultural standards which produce, for example, the belief that a scientific career is somehow ‘unladylike’ or that marriage should be enough of a career for any woman.” Among the high school students scoring in the top 10 percent on ability tests, 97 percent of those who didn’t go on to college were girls. Those who did go on, she argued, were squandered by a society that did not embrace their accomplishment or potential. The women of America—emancipated, educated, and enfranchised—were a “prodigious national extravagance.” While it was no longer unusual for women to desire and obtain college degrees, “we have never really expected women to use their talents and education to make significant intellectual or social advances,” Bunting wrote in the New York Times Magazine in 1961. “We were willing to open the doors but we did not think it important that they enter the promised land.”

Bunting had been thinking about these ideas well ahead of Betty Friedan, whose bestselling book, The Feminine Mystique, had been published in February 1963, two months before Nancy took her place in Watson’s lecture hall. Friedan’s book raged against a culture that had locked intelligent and well-educated women into lives of “quiet desperation”—kept from full participation and their full potential—by convincing them there was fulfillment in polite children, passive sex, and a perfectly waxed kitchen floor. Friedan had asked Bunting to collaborate on the book, and Bunting had met with her several times but soon concluded that Friedan was too angry, too intent on blaming men for women’s problems.

Bunting didn’t blame men. She thought the limits on women hurt everyone, as she wrote in the Times Magazine: “A dissatisfied woman is seldom either a good wife or a good mother.”

And she didn’t think women necessarily had to have careers. In fact, she suggested they work on the fringes, “where there is always room,” rather than compete directly against men. She urged her undergraduates to marry and have children and also to find “something awfully interesting that you want to work on awfully hard.” Having children would be a pause, not the termination, of intellectual pursuits outside the home. She envisioned the successful path of work and family ambitions like the new interstate highway system connecting postwar America, with women finding on- and off-ramps along the way.

She faulted previous generations of educated women for encouraging a negative stereotype of smart women: “For the most part, they became crusaders and reformers, passionate, fearless, articulate, but at times, loud,” she wrote in her annual president’s report in 1961. “Today, several generations later, the bitter battles for women’s rights are history. The cause has been won. The stereotype has disappeared and with it, the hard prejudice. But not altogether. For there is still prevalent a form of anti-intellectualism which insists that whatever her aspirations, a woman must eventually choose between career and marriage, and that if she attempts to combine the two, both will suffer and the marriage probably the more keenly.”

Bunting was fifty when she became president of Radcliffe, and saw her presidency as a perch from which to promote a happier image of a life that combined family and professional pursuits. She herself had raised four children and four goats, served on school and library boards, and grown all her own vegetables in between part-time positions at Bennington and at Yale, where her husband had been on the medical faculty. She had carried on despite adversity, taking on the job as dean of Douglass College, the women’s branch of Rutgers, after she was widowed at forty-four. And she saw Radcliffe as “a promising instrument for the attack that is called for.” As some trustees urged a merger with Harvard, she argued that it was a “negation of fact” to assume that women and men should be educated the same way. Women needed the same rigorous coursework as Harvard men, but their futures were in many ways more complicated, and they needed help planning “wisely and largely” so they would not lose their way. Bunting started what she called a “campaign versus apathy” that included a lecture series around Radcliffe Yard, thesis presentations with professors, but also “living room talks” of how to be a mother and wife.

Bunting noted approvingly the year Nancy arrived that the number of Radcliffe sophomores declaring English as their major was the lowest in a decade, and there had been a significant decline in history as well. Though those were still by far the most popular majors, Bunting wrote in her annual report, “The trend is welcomed as an indication that Radcliffe students are becoming a little more adventurous and imaginative and perhaps serious in their choice of major fields.” The number of Radcliffe students who married before graduation had fallen steadily—it had been 25 percent in 1955; it was about half that now. Perhaps because they were competing for fewer spots, Radcliffe women in Nancy’s class were increasingly more accomplished than Harvard men—“fearfully bright,” as Time magazine pronounced in its cover profile of the woman the magazine and her students called “Mrs. Bunting.” The women arrived with higher SAT scores and were far more likely to graduate with honors.

There were rumblings of the revolution that would bring coeducation and increased racial diversity at the end of the decade. Spring of 1963, the year Ann graduated, was the first time Radcliffe women would be given Harvard diplomas. (Graduation was still separate, and President Pusey continued to send a faculty member in his stead.) Radcliffe relaxed the social rules that had required girls to sign out of their houses and secure permission to be out past one o’clock in the morning. (While Radcliffe’s young women debated how this would affect dating and sex, Bunting thought the rules had disadvantaged young women who wanted to work all night in science labs.)

Still, Radcliffe girls who wanted a professional life had few role models on campus beyond Polly Bunting. The undergraduate faculty at Harvard had 295 tenured men, and 2 women—one, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, had spent thirty years as a lecturer before being granted tenure. (Her salary had been listed on the budget under “equipment.”) “What would happen if there was a genuine effort to see that one woman’s name was present on every slate considered, as is now customary in government with respect to Negroes, would be interesting to observe,” Bunting wrote in her annual report. Radcliffe administrators, she confessed, could themselves barely come up with candidates on the rare occasions they were asked. “Certainly it would be encouraging to Radcliffe students and probably revealing to Harvard men to have a greater number of able women scholars on the Faculty,” she wrote, “provided that they are qualified.”

It never occurred to Nancy to count the women in Bio 2. There were 47, and 178 men, about the same as the proportion of Radcliffe students to men at Harvard, and the number had been growing; the percentage of women declaring biology as their major had more than doubled over the previous decade; it was now the fifth most popular concentration.

Nancy had switched her major to biology only a few months before. She had arrived at Radcliffe intending to major in math, but her freshman adviser told her the first week that she was too far behind to possibly catch up; she would need two years of calculus, and Spence had not even offered it. She chose architecture as her major because she liked art and math and thought it might be a way to combine them, but the math classes didn’t move her the way she thought they would. Math didn’t seem to relate to anything she cared about. Her latest idea was to become a doctor. But the Bio 2 lectures so far had left her thinking she wasn’t cut out for medicine, either. Physiology fascinated her; how the heart pumps blood, the muscles contract, the kidney maintains the salt balance, was all so intricate and beautiful. But she didn’t think she could spend her time with sick people or tell parents their child was dying. She wanted to figure out what caused the disease in the first place, and how to fix it.

Watson and Crick’s discovery of the double helix had been described as a flash flood, arriving so quickly that few saw it coming, and forever reordering the scientific landscape. Scientists had barely agreed that DNA was the stuff of heredity, and they did not understand how it passed along traits. The double helix explained these mechanics—it was in the sequence of the always matching base pairs, and in the ability of DNA to make an exact copy of itself. Having understood this, the infant science of molecular biology was on its way to identifying the code that gave form and function to all of nature.

Watson and Crick, atheists both, believed that genes could replace religion as the organizing principle of the universe. Nancy was ripe for conversion. For the month of April, her life became all about Bio 2, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays at eleven. Watson fed the students the story of DNA like a mystery: How did it relay its message so that a gene knew to code for a protein, and a bacterium knew how to digest a certain sugar? How did genes know how and when to turn on and off? He started with the question of how cells grow and ended with what happened when they did not get the signal to stop growing and became cancer.

Nancy found herself on the edge of her seat, almost falling off if not for the wooden arm on the desk. She quickly came to guess what the next question was going to be before Watson asked it—an affinity she would later understand was called “good taste in science.”

She was hooked. So at the end of Watson’s lectures, she went to his office to ask if she could work in his lab.

In contrast to the puritan buildings of Harvard Yard, the Biological Laboratories building was whimsical and grand, not unlike Watson himself. Hidden on a path off Divinity Avenue, it was a massive U-shaped brick building surrounding a large quadrangle. Its facade had been drilled with friezes of animals representing the world’s four zoological regions, a sable antelope and Asiatic wapiti among them. Guarding the entrance on either side were two massive bronze rhinoceroses, sized to match the largest known of the specimen and named for England’s Queens Victoria and Elizabeth, Vicky and Bessie for short.

From his third-floor office overlooking the rhinos, Watson was busy overthrowing the old world order. He chafed against the traditions of Harvard, its refusal to give him a $1,000 raise that year despite the Nobel, its unwillingness to bestow biology with as much stature as physics or chemistry. He found the biology department fusty and lumbering, too focused on fields like ecology and zoology, which he considered extinct, hobbies at best. Like many scientists of his generation, he had been captivated reading Erwin Schrödinger’s What Is Life?, which posited that biology could be understood like physics and chemistry, as a set of universal laws. Molecular biology—and particularly the understanding of DNA, the most significant development of the new field—offered the possibility of understanding the chemistry behind the cellular processes that make up the living world. Why would you waste your time on taxonomies or the competition of the species when you could be figuring out how things worked in every last cell? He trained distinct disdain on Edward O. Wilson, the evolutionary biologist who rivaled Watson as a wunderkind but had been tenured a few months before him. Wilson, a genteel Southerner, in turn saw Watson as a rapacious megalomaniac with no time for collegiality or polite conversation, even a hello in the hallway. Wilson called him “the Caligula of biology,” brilliant but “the most unpleasant human being I have ever met.” After several tense years and frosty faculty meetings, Watson had succeeded in splitting the department in two, shipping the old-line biologists off to Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology across the street and recruiting physicists and chemists to join his own labs to further decode the workings of DNA.

While other students seemed afraid of Watson, the lectures had made Nancy bolder, and she knocked confidently on his door. She entered to a large airy office, one wall all books, the other, all windows. Diagonally in front of her was a piece of art Watson had purchased with his prize money from the Nobel, a life-size wooden likeness of a Papua New Guinean man, naked and roughly anatomically correct from the waist down. Watson knew she was a neophyte, but agreed to work with her without discussion or argument: “Sure,” he said, then jumped up from his sparsely covered desk and breezed around her to push through a door into a small room with a lab bench running along its length. He told her she would share it with two other Radcliffe students.

They shared the lab room with twelve Harvard undergraduates, but still it was an unusual concentration of women. Watson created room for women partly because he liked having them around. He was looking for a wife and thought he might find one at Radcliffe. He also thought they made life more interesting. At the Nobel ceremony in December 1962 he had convinced Princess Christina of Sweden to apply to Radcliffe and, once at home, arranged with Presidents Bunting and Pusey for her to attend. (Pusey had little patience with some of the antics of his young Nobelist, but wrote back, “She sounds like a most attractive young lady and I appreciate the interest you have taken in this matter.”) And Watson had an eye for talent: as his first female graduate student, he had taken on Joan Steitz, who was two years older than Nancy and would go on to be a Yale professor and one of the most highly regarded biologists of her generation. Steitz’s first choice had rejected her because she was a woman: “You’ll get married and you’ll have kids—then what good would a PhD have done you?”

Watson wanted to fill the lab with fun people who knew when to laugh and remained upbeat even when experiments went nowhere. He liked unconventional thinkers and saw Nancy that way. He was not interested in her romantically, considered her more handsome than pretty—his taste ran more traditional and blonder. He was fascinated that she had gone to Spence, which he considered one of the nation’s best schools. He was proudly Irish, from Chicago’s South Side and a family richer in intellect and culture than land or cash—Orson Welles was a distant cousin, and Watson himself had been a radio “Quiz Kid” and entered the University of Chicago at sixteen. His nose was still firmly pressed against the glass. He was intrigued that Nancy’s friends were debutantes from old-line families, Winthrops and Pratts. That, and her accent, which he mistook for Long Island lockjaw, made him think she was from New York society, not a building with an unfashionable address and no doorman.

The students in the lab were supposed to be doing their own experiments, but only those who had worked previous summers or semesters in labs were doing so. Nancy was still watching more than she was doing, but she was learning about science and how scientists worked. She found them open to her questions—and she had lots of them, her brain popping with ideas for experiments even if she didn’t yet know how to carry them out. The pastimes that had once consumed her—Saturday excursions to Crane Beach on the North Shore, parties in Eliot House with Brooke and his roommates—no longer held her interest. Only the lab did.

Watson could be demanding and at times dismissive, turning on his heel to leave if you bored him, which Nancy tried hard not to do. He soon began ducking through his door into her small lab space more regularly with “What’s new?” or “Lunch?” and calling her “kiddo.” Often he would deliver a bit of information, or a joke, transmitted in his staccato: dot dot dash dot dash. He’d be gone in a flash, the door still swinging on its hinges. She’d had other instructors who related well to students—Erich Segal, who later wrote Love Story, had been among them—but Watson was unusual. She knew his extraordinary accomplishment, yet still he spoke to students on their level, griped about professors the way they did. He soon became a friend and her idol, one of the most important people in her life.

Jim, as Nancy now called him, lived in a railroad apartment in the only house on Appian Way, near Radcliffe Yard, a narrow white clapboard building where he threw crowded parties that mixed professors and students and the occasional celebrity—one party was for the princess, another for Melina Mercouri, the Greek star of the hit film Never on Sunday. If it was unusual for faculty and students to socialize like this, science was unusual, and the lab like a family, its members climbing every year onto the rhinos in front of the building for goofy group portraits. Jim’s widowed father lived in an apartment downstairs. Jim doted on him—they shared a lifelong passion for bird-watching and the Democratic Party—and took him out to dinner each week. Jim began inviting Nancy and sometimes Ann, who was living in Cambridge after graduation, or their mother, who was living in New York but visited often after the death of her husband.

The Watsons loved to argue and talk politics, which Nancy’s family had never done. It was her first stirring of a political consciousness. Jim and his father considered themselves New Deal socialists, had left the Catholic Church but kept its concern for the poor; Nancy knew only that her mother had liked FDR and that her father had been a New Hampshire Republican.

She was the happiest she had been since childhood. The lab had opened up a world she had not known existed, much less thought she might inhabit. The field was so new, the universe of molecular biologists so small, and Watson so central to it that it was all unfolding in front of her. He and his friends were still identifying the genetic code, the three-letter labels for the twenty amino acids that translate DNA to protein. They had formed what they called the RNA tie club to share notes that might advance the understanding; members were initiated with a woolen necktie embroidered with a helix and a pin with a three-letter code. Those members included some of the biggest names in science: Sydney Brenner, Edward Teller, Richard Feynman.

Every afternoon at three, students and scientists from the lab would crowd into a small square room for tea and chocolate chip cookies fetched from Savenor’s by a receptionist on her old Raleigh bike. Jim had adopted the tradition from his time at the Cavendish Lab in Cambridge, England. Nancy, her fellow students, and some technicians filed in first, followed by the postdocs and then the faculty members. Jim typically entered last, silencing the room as the others waited to hear what gossip or discovery he had learned that day. The information he shared could be monumental: one day, it was that the genetic code was universal—the transfer of information from genes was the same whether the creation was a virus or a fly’s wing, the leaf of a plant or the human brain.

Nancy saw how small facts from individual experiments added up to larger insights that together could answer the big questions. She began to see the elegant logic of biology; it was profound, mysterious, and yet totally sensible.

She had found her place in the world, her purpose. Bio was her “awfully interesting” thing, though she quickly concluded that Mrs. Bunting must be withholding some secret to explain how anyone with a family could also have this consuming a career. The students and postdocs worked around the clock, coming in at least six days a week and often a seventh if they needed to check a tube or skim a gel from a machine when trying to isolate a protein or a compound. Watson set the example. One Saturday night, Nancy noticed a light on under the door to his office. She pushed through to see what he was working on. He was at his desk writing what would soon become the first and classic textbook of the new field, Molecular Biology of the Gene. He looked up at Nancy, and his face told her that he did not want to be interrupted.

Nancy’s roommate, Deming Pratt, saw few charms in Jim. Deming thought his gestures awkward, his clothing too baggy. He didn’t even look you in the eye. Nancy was amused by his aspirations to the world of Long Island’s Gold Coast and membership at the Piping Rock country club, picked up during his summer stints at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Deming, who was of that world, considered it unseemly, almost Gatsbyesque, though she did grant Jim’s request to attend her twenty-first birthday at her family’s estate. (There she noted that he couldn’t waltz.)

Nancy’s boyfriend, Brooke Hopkins, sometimes joined her outings with Jim, but professed little interest in her new world. Brooke and Nancy had met at a freshman mixer her first week, and he was the kind of boyfriend she had dreamed of in girls’ school, where her classmates had convinced her that good grades would scare boys away. Six foot five, a rower with dark reddish hair and brown eyes, he came from a conservative Social Register family in Baltimore, had gone to Hotchkiss and gotten into Harvard on mediocre grades and, he presumed, family legacy. He was doing his best to rebel, listening to jazz and reading Freud and James Baldwin. He had been recruited by the Porcellian Club, the most elite of Harvard’s all-male social clubs and the proving ground for the future leaders of American social, political, and business institutions, who, it was understood, were almost always white and rarely Jewish. He’d joined Fly Club instead, thinking it more progressive.

Ann divided the men of Harvard into those who wore dark socks and those who wore white: the dark socks were worn by the boys who had gone to boarding or elite private schools, the white socks were worn by the boys from public schools, Bronx Science or Stuyvesant if they were lucky. These white-sock boys were becoming Nancy’s friends in the lab, and she felt more at ease with them than she did the boys with dark socks. Science was becoming her social world, too.

The lab brought many famous visitors, none more eagerly anticipated than Francis Crick. Crick was twelve years older than Jim, and Jim revered him. Jim quoted him constantly, aped his confidence and his English intonations. (“Both young men are somewhat mad hatters who bubble over about their new structure in characteristic Cambridge style,” a visitor from the Rockefeller Foundation to the lab wrote shortly after their discovery of the double helix. “It is hard to realize one of them is an American.”) It was close to graduation in the spring of 1964, and Watson had planned a big party in his apartment on Appian Way in Crick’s honor, inviting students along with some of Harvard’s most prominent faculty. Nancy made a mental note not to drink too much; Watson served a potent cognac-and-wine punch, and she wanted to stay sober enough to have an intelligent conversation with Crick. She went to do some work in the lab early that afternoon in the hope she’d get the chance to meet him there first.

Francis Harry Compton Crick had grown up the son of a shoemaker in the British Midlands, but carried himself with the satisfaction of an aristocrat, a man used to being acclaimed as a genius, as almost everyone who knew him now did. He was tall, handsome in an imperious way, with a prominent nose and chin—a profile worthy of a coin—and an arch smile. Nancy would have recognized him from the photograph in Jim’s office of the two men gazing at their six-foot model of the double helix, had she time. But Crick arrived so suddenly behind her in the little side lab that she realized he was there only because his hands were on her breasts.

“What are you working on?” he asked, his voice as loud as its reputation.

Nancy froze. Crick was married, and she had heard he was a womanizer; a former grad student from Watson’s lab had told her that he knew a postdoc who had slept with him in England, that Crick’s beautiful and cultured wife knew about his infidelities but looked the other way. But Nancy hadn’t dwelled on the gossip, and she hadn’t considered this would come to her. She’d heard similar rumors about Jim, and he had never made a move on her. She’d never even seen Jim with a date.

She wriggled on her lab stool to break free of Crick’s clutch and stammered, trying to find a way to move the conversation onto science. She thought first that she didn’t want to embarrass him, second that she didn’t want to embarrass herself. She had to be able to face him that night.

She told him she was studying bacterial viruses but that she really wanted to study the repressor function of genes, though she realized that was too challenging a problem right now. She kept talking, holding out hope he would see her as a serious person.

Then just as suddenly, Jim burst through the door, clapped his hand on Crick’s back to greet him, and steered him back into his office. Nancy was alone again. If Watson had seen anything, he didn’t say so. Nancy went to the party that night and held her liquor. It was crowded, with dancing, as usual. Jim urged her to stay to the end, which she did, hanging on the small circle talking science around the famous duo. Then, because no Radcliffe girl would walk through Cambridge alone at one o’clock in the morning, Watson and Crick, purveyors of the secret of life, the great men who generations of biology students would know by their conjoined surnames, escorted her along the brick sidewalks of Garden Street and back to her dorm.

It had been, Nancy thought as the heavy door closed behind her, a spectacular day.

She could have done without Crick groping her, but after the evening at Watson’s she had almost forgotten about it. What filled her head instead was newfound assurance, confidence that she had found the meaning she had been looking for. She liked her private-school friends well enough, liked to go to their parties. But these other people were on a higher plane—the ideas they discussed, the questions about life they were poised to answer. She wouldn’t quite say she felt at home in their world, at least not yet, but even to be at the edge of their conversations—it was the most exciting thing that had ever happened to her.

The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

- Genres: History, Nonfiction

- paperback: 448 pages

- Publisher: Scribner

- ISBN-10: 1982131845

- ISBN-13: 9781982131845