Excerpt

Excerpt

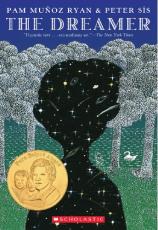

The Dreamer

Rain

On a continent of many songs, in a country shaped like the arm of a tall guitarrista, the rain drummed down on the town of Temuco.

Neftalí Reyes sat in his bed, propped up by pillows, and stared at the schoolwork in front of him. His teacher called it simple addition, but it was never simple for him. How he wished the numbers would disappear! He squeezed his eyes closed and then opened them.

The twos and threes lifted from the page and waved for the others to join them. The fives and sevens sprang upward, and finally, after much prodding, the fours, ones, and sixes came along. But the nines and zeros would not budge, so the others left them. They held hands in a long procession of tiny figures, flew across the room, and escaped through the window crack. Neftalí closed the book and smiled.

He certainly could not be expected to finish his homework with only the lazy zeros and nines lolling on the page.

He slowly stepped out of bed and to the window, leaning his forehead against the pane and gazing into the backyard. He knew that he should rest in order to recuperate from his illness. He knew that when he wasn’t resting, he should catch up on his studies. But there were so many distractions.

Outside, the winter world was gray and sodden. The earth turned to mud, and a small stream flowed through a hole in the ramshackle fence. At the moment, no one lived next door. Still, Neftalí always imagined a friend on the other side, waiting for him – someone who might enjoy watching flotsam drift downriver, who collected twisted sticks, liked to read, and was not good at mathematics, either.

He heard footsteps. Was it Father?

He had been away, working on the railroad for a week, and was due home today. Neftalí’s heart pounded and his round brown eyes grew large with panic.

The footsteps came closer.

Clump.

Clump.

Clump.

Clump.

Neftalí reached up and smoothed his thick black hair. Was it out of place? He held up his hands and looked at his thin fingers. Were they clean enough?

The idea of having to confront Father made his arms tingle and his skin feel as if it were shrinking. He took a deep breath and held it.

The footsteps passed his room and continued down the hall.

Neftalí exhaled.

It must have been Mamadre, his stepmother, in her wooden-heeled shoes. He listened until he was sure that no one was near, then he turned to the window again.

Raindrops strummed across the zinc roof. Water mysteriously trilled above him, worming its way indoors. Weepy puddles dripped from the ceiling, filling the pots that had been poised to catch them.

plip – plip

plop

bloop, bloop, bloop

oip, oip, oip, oip

plip – plip

plip – plip

plop

tin,

tin,

tin,

tin,

tin

plop

plip – plip

bloop, bloop, bloop

oip, oip, oip, oip

tin,

tin,

tin,

tin,

tin

plip – plip

plip – plip

plop

As Neftalí listened to the piano of wet notes, he looked up at the Andes mountains, hovering like a white-robed choir. He looked out at the river Cautín, pattering through the forest. He closed his eyes and wondered what lay beyond, past the

places of Labranza, Boroa, and Ranquilco, where the sea plucked at the rugged land.

The window opened. A carpet of rain swept in and carried Neftalí to the distant ocean he had only seen in books. There, he was the captain of a ship, its prow slicing through the blue. Salt water sprayed his cheeks. His clothes fluttered against

his body. He gripped the mast, looking back on his country, Chile.

Neftalí? Who spoons the water from the cloud to the snowcap to the river and feeds it to the hungry ocean?

The screech of a conductor’s whistle snapped Neftalí to attention. He jerked around.

Father’s body filled the doorway.

Neftalí shuddered.

“Stop that incessant daydreaming!” The white tip of Father’s yellow beard quivered as he clenched and unclenched his narrow jaw. “And why are you out of bed?”

Neftalí averted his eyes.

“Do you want to be a skinny weakling forever and amount to nothing?”

“N-n-n-no, Father,” stammered Neftalí.

“Your mother was the same, scribbling on bits of paper, her mind always in another world.”

Neftalí rubbed his temples. He had never known his mother. She had died two months after he was born. Was Father right? Could daydreaming make you weak? Had it made his mother so weak that she had died?

Mamadre hurried into the room.

Father pointed at her. “You need to watch him more closely. He must stay in bed or he will never get stronger.” As he bounded from the doorway, the floor shook.

Mamadre took Neftalí’s hand, gently helped him into bed, and tucked the blankets around him. “Your mother did not die from her imagination,” she whispered. “It was a fever. And look at me. I am small and many say much too thin. I may not appear big and strong on the outside, but I am perfectly capable on the inside . . . just like you.” She stroked his head. “I know it is hard to spend so many days in bed.”

“I f-f-feel . . . f-f-fine,” said Neftalí, reaching up to touch her black hair, which was pulled into a tight bun at the back of her neck.

“Just one more day,” said Mamadre. “I will read to you to help pass the time.”

Within the lull of Mamadre’s soothing voice, Neftalí lost himself in the legends of swashbucklers and giants. There, his painful shyness stayed in the back of his mind. There, he could not be called “Shinbone” because of his thin and sickly body, or chosen last for a street game by the neighborhood boys.

Between the pages, he forgot that he stuttered when he spoke. He saw himself healthy and strong like his older brother, Rodolfo; cheerful like his little sister, Laurita; and confident and intelligent like his uncle Orlando, who owned the local newspaper. While the pages turned, he even dared to imagine himself with a friend.

After Mamadre finished reading and slipped away, Neftalí studied the cracks in the ceiling. They looked like roads on a map, and he wondered to which country they belonged.

He sighed. It had not mattered one bit what Father had said about daydreaming. Neftalí could not stop.

Every curious detail of his life taunted him.

His mind wandered:

To the monster storm raging outside, which startled the roof. To the distant rumble of the dragon volcano, Mount Llaima, which made the floors hiccup. To the makeshift walls of his timid house, trembling and cowering from the roar of passing trains. To the haphazard design of the room with incomplete stairs, which might have led to a castle on another floor, but had long been deserted in the middle of construction.

Neftalí? To which mystical land does an unfinished staircase lead?

The next day, Mamadre was far more watchful, and Neftalí could not escape from

his bed. Instead, he begged Laurita to be his ambassador at the window.

“T-t-t-tell me all that you can s-see. Please. ¿Porfa?”

Laurita nodded. She was only four and too short to see out. She pushed a chair to the window and climbed onto the seat. Then she leaned forward. Her round black eyes, heavy lashes, and sleek hair made her look like a little bird perched at the sill. “I see rain . . . bumpy sky . . . wet leaves . . . one boot missing the other . . . muddy puddles . . . un perro callejero . . . ”

“T-t-tell me about the stray dog,” said Neftalí. “What color is it?”

“It is so wet, I cannot say. Maybe brown.

Maybe black,” said Laurita.

“T-t-tell me about the boot that is m-m-missing the other.”

“It has no shoestrings. It looks lonely.”

“Tomorrow, when I am allowed up, I will rescue it and add it to my c-c-collections.”

“But you already have so many rocks and sticks and nests. And the boot will be so dirty,” said Laurita. “And you do not know where it has been. Or who has worn it.”

“That is true,” said Neftalí. “B-b-but I will clean it. Maybe it belonged to a stonemason, and by owning it, I will receive his strength. Or maybe it belonged to a b-b-baker, and once I run my hands over the leather, I will know how to make b-bread.”

Laurita giggled. “You are silly, Neftalí.”

Just then, Mamadre appeared in the doorway. “Laurita, Valeria is here to play with you. And, Neftalí, you need a nap or you will not be able to go back to school tomorrow.” She came into the room, kissed his forehead, and pulled the blanket up to his chin. “You look fine on the outside, my son. How do you feel on the inside?”

“Not tired. P-p-please, Mamadre, may I read for a while?”

“That is what I deserve for teaching you before you even started school.” Mamadre nodded and smiled as she left the room. “One story.”

Neftalí grabbed a book from the bedside table. Even though he did not know all of the words, he read the ones he knew. He loved the rhythm of certain words, and when he came to one of his favorites, he read it over and over again: locomotive, locomotive, locomotive. In his mind, it did not get stuck. He heard the word as if he had said it out loud – perfectly.

Neftalí climbed out of bed, retrieved a pencil and paper, and copied the word.

LOCOMOTIVE

He folded the paper into a small square and put it in a dresser drawer already crammed with other words he’d written on tiny, doubled-over pieces of paper. Then he crawled into bed.

Father’s question from yesterday found its way into his thoughts. Do you want to be a skinny weakling forever and amount to nothing?

The words in the drawer shuffled. The drawer opened. The small pieces of paper floated into the room and arranged and rearranged themselves into curious patterns above his head.

CHOCOLATE

OREGANO

IGUANA

TERRIBLE

LOCOMOTIVE

Neftalí sat up, rubbed his eyes, and looked around the room. The words were no longer there. He slid from the bed, tiptoed to the drawer, and opened it.

All of the words were sleeping.

Excerpted from THE DREAMER © Copyright 2012 by written by Pam Muñoz Ryan illustrated by Peter Sís. Reprinted with permission by Scholastic Press, an imprint of Scholastic Inc. All rights reserved.

Click here now to buy this book from Amazon.com.

The Dreamer

- Genres: Children's, Fiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Scholastic Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0439269989

- ISBN-13: 9780439269988