Excerpt

Excerpt

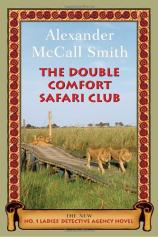

The Double Comfort Safari Club: The New No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency Novel

YOU DO NOT CHANGE PEOPLE BY SHOUTING AT THEM

No car, thought Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni, that great mechanic, and

good man. No car . . .

He paused. It was necessary, he felt, to order the mind when one

was about to think something profound. And Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni was

at that moment on the verge of an exceptionally important thought,

even though its final shape had yet to reveal itself. How much

easier it was for Mma Ramotswe --- she put things so well, so

succinctly, so profoundly, and appeared to do this with such little

effort. It was very different if one was a mechanic, and therefore

not used to telling people --- in the nicest possible way, of

course --- how to run their lives. Then one had to think quite hard

to find just the right words that would make people sit up and say,

“But that is very true, Rra!” Or, especially if you

were Mma Ramotswe, “But surely that is well known!”

He had very few criticisms to make of Precious Ramotswe, his

wife and founder of the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, but

if one were to make a list of her faults --- which would be a

minuscule document, barely visible, indeed, to the naked eye ---

one would perhaps have to include a tendency (only a slight

tendency, of course) to claim that things that she happened to

believe were well known. This phrase gave these beliefs a sort of

unassailable authority, the status that went with facts that all

right-thinking people would readily acknowledge --- such as the

fact that the sun rose in the east, over the undulating canopy of

acacia that stretched along Botswana’s border, over the

waters of the great Limpopo River itself that now, at the height of

the rainy season, flowed deep and fast towards the ocean half a

continent away. Or the fact that Seretse Khama had been the first

President of Botswana; or even the truism that Botswana was one of

the finest and most peaceful countries in the world. All of these

facts were indeed both incontestable and well known; whereas Mma

Ramotswe’s pronouncements, to which she attributed the

special status of being well known, were often, rather, statements

of opinion. There was a difference, thought Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni,

but it was not one he was planning to point out; there were some

things, after all, that it was not helpful for a husband

to say to his wife and that, he thought, was probably one of

them.

Now, his thoughts having been properly marshalled, the right

words came to him in a neat, economical expression: No car is

entirely perfect. That was what he wanted to say, and these

words were all that was needed to say it. So he said it once more.

No car is entirely perfect.

In his experience, which was considerable --- as the proprietor

of Tlokweng Road Speedy Motors and attending physician, therefore,

to a whole fleet of middle-ranking cars --- every vehicle had its

bad points, its foibles, its rattles, its complaints; and this, he

thought, was the language of machinery, those idiosyncratic engine

sounds by which a car would strive to communicate with those with

ears to listen, usually mechanics. Every car had its good points

too: a comfortable driving seat, perhaps, moulded over the years to

the shape of the car’s owner, or an engine that started the

first time without hesitation or complaint, even on the coldest

winter morning, when the air above Botswana was dry and crisp and

sharp in the lungs. Each car, then, was an individual, and if only

he could get his apprentices to grasp that fact, their work might

be a little bit more reliable and less prone to require redoing by

him. Push, shove, twist: these were no mantras for a good

mechanic. Listen, coax, soothe: that should be the motto

inscribed above the entrance to every garage; that, or the words

which he had once seen printed on the advertisement for a garage in

Francistown: Your car is ours.

That slogan, persuasive though it might have sounded, had given

him pause. It was a little ambiguous, he decided: on the one hand,

it might be taken to suggest that the garage was in the business of

taking people’s cars away from them --- an unfortunate choice

of words if read that way. On the other, it could mean that the

garage staff treated clients’ cars with the same care that

they treated their own. That, he thought, is what they meant, and

it would have been preferable if they had said it. It is always

better to say what you mean --- it was his wife, Mma Ramotswe,

who said that, and he had always assumed that she meant it.

No, he mused: there is no such thing as a perfect car, and if

every car had its good and bad points, it was the same with people.

Just as every person had his or her little ways --- habits that

niggled or irritated others, annoying mannerisms, vices and

failings, moments of selfishness --- so too did they have their

good points: a winning smile, an infectious sense of humour, the

ability to cook a favourite dish just the way you wanted it.

That was the way the world was; it was composed of a few almost

perfect people (ourselves); then there were a good many people who

generally did their best but were not all that perfect (our friends

and colleagues); and finally, there were a few rather nasty ones

(our enemies and opponents). Most people fell into that middle

group --- those who did their best --- and the last group was,

thankfully, very small and not much in evidence in places like

Botswana, where he was fortunate enough to live.

These reflections came to Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni while he was

driving his tow-truck down the Lobatse Road. He was on what Mma

Ramotswe described as one of his errands of mercy. In this case he

was setting out to rescue the car of one Mma Constance Mateleke, a

senior and highly regarded midwife and, as it happened, a

long-standing friend of Mma Ramotswe. She had called him from the

roadside. “Quite dead,” said Mma Mateleke through the

faint, crackling line of her mobile phone. “Stopped. Plenty

of petrol. Just stopped like that, Mr. Matekoni. Dead.”

Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni smiled to himself. “No car dies for

ever,” he consoled her. “When a car seems to

die, it is sometimes just sleeping. Like Lazarus, you know.”

He was not quite sure of the analogy. As a boy he had heard the

story of Lazarus at Sunday School in Molepolole, but his

recollection was now hazy. It was many years ago, and the stories

of that time, the real, the made-up, the long-winded tales of the

old people --- all of these had a tendency to get mixed up and

become one. There were seven lean cows in somebody’s dream,

or was it five lean cows and seven fat ones?

“So you are calling yourself Jesus Christ now, are you,

Mr. Matekoni? No more Tlokweng Road Speedy Motors, is it? Jesus

Christ Motors now?” retorted Mma Mateleke. “You say

that you can raise cars from the dead. Is that what you’re

saying?”

Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni chuckled. “Certainly not. No, I am

just a mechanic, but I know how to wake cars up. That is not a

special thing. Any mechanic can wake a car.” Not apprentices,

though, he thought.

“We’ll see,” she said. “I have great

faith in you, Mr. Matekoni, but this car seems very sick now. And

time is running away. Perhaps we should stop talking on the phone

and you should be getting into your truck to come and help

me.”

So it was that he came to be travelling down the Lobatse Road,

on a pleasantly fresh morning, allowing his thoughts to wander on

the broad subject of perfection and flaws. On either side of the

road the country rolled out in a grey-green carpet of thorn bush,

stretching off into the distance, to where the rocky outcrops of

the hills marked the end of the land and the beginning of the sky.

The rains had brought thick new grass sprouting up between the

trees; this was good, as the cattle would soon become fat on the

abundant sweet forage it provided. And it was good for Botswana

too, as fat cattle meant fat people --- not too fat, of course, but

well-fed and prosperous-looking; people who were happy to be who

they were and where they were.

Yes, thought Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni, even if no country was

absolutely perfect, Botswana, surely, came as close as one could

get. He closed his eyes in contentment, and then quickly remembered

that he was driving, and opened them again. A car behind him ---

not a car that he recognised --- had driven to within a few feet of

the rear of his tow-truck, and was aggressively looking for an

opportunity to pass. The problem, though, was that the Lobatse Road

was busy with traffic coming the other way, and there was a vehicle

in front of Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni that was in no hurry to get

anywhere; it was a driver like Mma Potokwane, he imagined, who

ambled along and frequently knocked the gear-stick out of gear as

she waved her hand to emphasise some point she was making to a

passenger. Yet Mma Potokwane, and this slow driver ahead of him, he

reminded himself, had a right to take things gently if they wished.

Lobatse would not go away, and whether one reached it at eleven in

the morning or half past eleven would surely matter very

little.

He looked in his rear-view mirror. He could not make out the

face of the driver, who was sitting well back in his seat, and he

could not therefore engage in eye contact with him. He should calm

down, thought Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni, rather than . . . His line of

thought was interrupted by the sudden swerving of the other vehicle

as it pulled over sharply to the left. Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni, well

versed as he was in the ways of every sort of driver, gripped his

steering wheel hard and muttered under his breath. What was being

attempted was that most dangerous of manoeuvres --- overtaking on

the wrong side.

He steered a steady course, carefully applying his brakes so as

to allow the other driver ample opportunity to effect his passing

as quickly as possible. Not that he deserved the consideration, of

course, but Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni knew that when another driver did

something dangerous it was best to allow him to finish what he was

doing and get out of the way.

In a cloud of dust and gravel chips thrown up off the unpaved

verge of the road, the impatient car shot past, before swerving

again to get back onto the tarmac. Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni felt the

urge to lean on his horn and flash his lights in anger, but he did

neither of these things. The other driver knew that what he had

done was wrong; there was no need to engage in an abusive exchange

which would lead nowhere, and would certainly not change that

driver’s ways. “You do not change people by shouting at

them,” Mma Ramotswe had once observed. And she was right:

sounding one’s horn, shouting --- these were much the same

things, and achieved equally little.

And then an extraordinary thing happened. The impatient driver,

his illegal manoeuvre over, and now clear of the tow-truck, looked

in his mirror and gave a scrupulously polite thank-you wave to Mr.

J.L.B. Matekoni. And Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni, taken by surprise,

responded with an equally polite wave of acknowledgement, as one

would reply to any roadside courtesy or show of good driving

manners. That was the curious thing about Botswana; even when

people were rude --- and some degree of human rudeness was

inevitable --- they were rude in a fairly polite way.

Excerpted from THE DOUBLE COMFORT SAFARI CLUB: The New No. 1

Ladies' Detective Agency Novel © Copyright 2011 by Alexander

McCall Smith. Reprinted with permission by Pantheon. All rights

reserved.