Excerpt

Excerpt

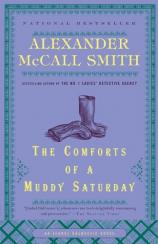

The Comforts of a Muddy Saturday: An Isabel Dalhousie Novel

What made Isabel Dalhousie think about chance? It was one of

those curious coincidences --- an inconsequential one --- as when

we turn the corner and find ourselves face-to-face with the person

we’ve just been thinking about. Or when we answer the

telephone and hear at the other end the voice of the friend we had

been about to call. These things make us believe either in

telepathy --- for which there is as little hard evidence as there

is, alas, for the existence of Santa Claus --- or in pure chance,

which we flatter ourselves into thinking plays a small role in our

lives. Yet chance, Isabel thought, determines much of what happens

to us, from the original birth lottery onwards. We like to think

that we plan what happens to us, but it is chance, surely, that

lies behind so many of the great events of our lives --- the

meeting with the person with whom we are destined to spend the rest

of our days, the receiving of a piece of advice which influences

our choice of career, the spotting of a particular house for sale;

all of these may be down to pure chance, and yet they govern how

our lives work out and how happy --- or unhappy --- we are going to

be.

It happened when she was walking with Jamie across the Meadows, the

large, tree-lined park that divides South Edinburgh from the Old

Town. Jamie was her . . . What was he? Her lover --- her younger

lover --- her boyfriend; the father of her child. She was reluctant

to use the word partner because it has associations of

impermanence and business arrangements. Jamie was most definitely

not a business arrangement; he was her north, her south, to quote

Auden, whom she had recently decided she would quote less

frequently. But even in the making of that resolution, she had

found a line from Auden that seemed to express it all, and had

given up on that ambition. And why, she asked herself, should one

not quote those who saw the world more clearly than one did

oneself?

Her north, her south; well, now they were walking north, on one of

those prolonged Scottish summer evenings when it never really gets

dark, and when one might forget just how far from south one really

is. The fine weather had brought people out onto the grass; a group

of young men, bare-chested in the unaccustomed warmth, were playing

a game of football, discarded tee-shirts serving as the goal

markers; a man was throwing a stick for a tireless border collie to

fetch; a young couple lay stretched out, the girl’s head

resting on the stomach of a bearded youth who was looking away, at

something in the sky that only he could see. The air was heavy, and

although it would soon be eight o’clock, there was still a

good deal of sunlight about --- soft, slanting sunlight, with the

quality that goes with light that has been about for the whole day

and is now comfortable, used.

The coincidence was that Jamie should suddenly broach the subject

of what it must be like to feel thoroughly ashamed of oneself.

Later on she asked herself why he had suddenly decided to talk

about that. Had he seen something on the Meadows to trigger such a

line of thought? Strange things were no doubt done in parks by

shameless people, but hardly in the early evening, in full view of

passersby, on an evening such as this. Had he seen some shameless

piece of exhibitionism? She had read recently of a Catholic priest

who went jogging in the nude, and explained that he did so on the

grounds that he sweated profusely when he took exercise. Indeed,

for such a person it might be more convenient not to be clad, but

this was not Sparta, where athletes disported naked in the

palaestra; this was Scotland, where it was simply too cold

to do as in Sparta, no matter how classically minded one might

be.

Whatever it was that prompted Jamie, he suddenly remarked:

“What would it be like not to be able to go out in case

people recognised you? What if you had done something so . . . so

appalling that you couldn’t face people?”

Isabel glanced at him. “You haven’t, have

you?”

He smiled. “Not yet.”

She looked up at the skyline, at the conical towers of the old

Infirmary, at the crouching lion of Arthur’s Seat in the

distance, beyond a line of trees. “Some who have done

dreadful things don’t feel it at all,” she said.

“They have no sense of shame. And maybe that’s why they

did it in the first place. They don’t care what others think

of them.”

Jamie thought about this for a moment. “But there are plenty

of others, aren’t there? People who have done something out

of character. People who have a conscience and who yet suddenly

have given in to passing temptation. Some dark urge. They must feel

ashamed of themselves, don’t you think?”

Isabel agreed. “Yes, they must. And I feel so sorry for

them.” It had always struck her as wrong that we should judge

ourselves --- or, more usually, others --- by single acts, as if a

single snapshot said anything about what a person had been like

over the whole course of his life. It could say something, of

course, but only if it was typical of how that person behaved;

otherwise, no, all it said was that at that moment, in those

particular circumstances, temptation won a local victory.

They walked on in silence. Then Isabel said, “And what about

being made to feel ashamed of what you are? About being

who you are.”

“But do people feel that?”

Isabel thought that they did. “Plenty of people feel ashamed

of being poor,” she said. “They shouldn’t, but

many do. Then some feel ashamed of being a different colour from

those around them. Again, they shouldn’t. And others feel

ashamed of not being beautiful, of having the wrong sort of chin.

Of having the wrong number of chins. All of these

things.”

“It’s ridiculous.”

“Of course it is.” Jamie, she realised, could say that;

the blessed do not care from what angle they are regarded, as Auden

. . . She stopped herself, and thought instead of moral progress,

of how much worse it had been only a few decades ago. Things had

changed for the better: now people asserted their identities with

pride; they would not be cowed into shame. Yet so many lives had

been wasted, had been ruined, because of unnecessary shame.

She remembered a friend’s mother who had discovered, at the

age of twelve, that she was illegitimate, that the father who had

been said to have been killed in an accident was simply not there,

a passing, regretted dalliance that had resulted in her birth.

Today that meant very little, when vast cohorts of children sprang

forth from maternity hospitals without fathers who had signed up to

anything, but for that woman, Isabel had been told, the rest of her

life, from twelve onwards, was to be spent in shame. And with that

shame there came the fear that others would find out about her

illegitimacy, would stumble upon her secret. Stolen lives, Isabel

thought, lives from which the joy had been extracted; and yet we

could not banish shame altogether --- she herself had written that

in one of her editorials in the Review of Applied Ethics,

in a special issue on the emotions. Without shame, guilt became a

toothless thing, a prosecutor with no penalties up his

sleeve.

They were on their way to a dinner party, and had decided to walk

rather than call a taxi, since the evening was so inviting. Their

host lived in Ramsay Garden, a cluster of flats clinging to the

edge of the Castle Rock like an impossible set constructed by some

operatic visionary and then left for real people to move into. From

the shared courtyard below, several cream-harled buildings, with

tagged-on staircases and balconies, grew higgledy-piggledy

skywards, their scale and style an odd mixture of Arts and Crafts

and Scottish baronial. It was an expensive place to live, much

sought-after for the views which the flats commanded over Princes

Street and the Georgian New Town beyond.

She had told Jamie who their hosts were, but he had forgotten, and

he asked her again as they climbed the winding stairway to the

topmost flat. She found herself thinking: Like all men, he does not

listen. Men switch off and let you talk, but all the time something

else is going on in their minds.

“Fleurs-de-lis,” said Isabel, running her hand along

the raised plaster motifs on the wall of the stairway. “Who

are they? People I don’t know very well. And I think that I

owe them, anyway. I was here for dinner three years ago, if I

remember correctly. And I never invited them back. I meant to, but

didn’t. You know how it is.”

She smiled at herself for using the excuse You know how it

is. It was such a convenient, all-purpose excuse that one

could tag it on to just about anything. And what did it say? That

one was human, and that one should be forgiven on those grounds? Or

that the sheer weight of circumstances sometimes made it difficult

to live up to what one expected of oneself? It was such a flexible

excuse, and one might use it for the trivial or the not so trivial.

Napoleon, for instance, might say, Yes, I did invade Russia;

I’m so sorry, but you know how it is.

Jamie ended her reverie. “They’ve forgiven you,”

he said. “Or they weren’t counting.”

“Do you have to invite people back?” Isabel asked.

“Is it wrong to accept an invitation if you know that you

won’t reciprocate?”

Jamie ran his finger across the fleurs-de-lis. “But you

haven’t told me who they are.”

“I was at school with her,” said Isabel. “She was

very quiet. People laughed at her a bit --- you know how children

are. She had an unfortunate nickname.”

“Which was?”

Isabel shook her head. “I’m sorry, Jamie, I

shouldn’t tell you.” That was how nicknames were

perpetuated; how her friend, Sloppy Duncan, was still Sloppy Duncan

thirty years after the name was first minted.

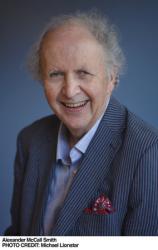

Excerpted from THE COMFORTS OF A MUDDY SATURDAY: An Isabel

Dalhousie Novel © Copyright 2010 by Alexander McCall Smith.

Reprinted with permission by Pantheon. All rights reserved.