Excerpt

Excerpt

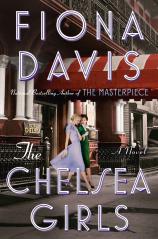

The Chelsea Girls

Chapter One

Hazel

Naples, Italy, April 1945

She hated Maxine Mead, and Italy, on first sight.

When Hazel had first auditioned for the USO tour, back in New York, she’d imagined arriving abroad and gingerly stepping off a plane to a cheering group of GIs. The stage would be a grand opera house or something similarly picturesque, like what she’d seen in the newsreels of Marlene Dietrich and Bob Hope entertaining the troops. Hazel would be sure to call them men, not boys, as the USO Actors’ Handbook advised. After all, many of them had been fighting for four years now. They deserved respect as well as some wholesome entertainment, a respite from the fighting.

Upon boarding the Air Corps plane at LaGuardia Airport, Hazel was informed that she’d be replacing a member of an all‑female acting troupe who’d come down with jaundice. Not until the noisy tin can of a cargo plane was aloft was she told her destination: Naples, Italy.

After a bumpy landing, Hazel lugged her two suitcases off the plane and stood on the tarmac, exhausted and confused, waiting for someone to tell her where to go, what to do next. The stifling heat was made worse by the fact that she’d been given the winter uniform, including wool stockings and thick winter panties. Every inch of her from the waist down itched as though she had ants crawling up her sweaty legs. Her uniform—a greenish‑gray skirt, white blouse, long black tie, and garrison cap that she’d admired in the mirror back in New York—was now a stinking, wrinkled mess.

Finally, a soldier pulled up in a Jeep and called out her name. He tossed her suitcases in the back before helping her into the passenger seat.

They lurched off over a road battered by potholes, passing demolished apartment buildings and churches. Several women picked through a pile of garbage by the side of the road, stopping to stare at Hazel with dead eyes before turning back to their work. A group of ragged, emaciated children, one of whom sucked on his dirty fingers, watched the scavengers. Yet across the street, a tidy line of schoolboys walked past the desolation as if nothing were wrong. The air smelled of rotting vegetables; dust kicked into Hazel’s nose and made her sneeze. Early in the war, the newspapers had published aerial photos of the city showing almost all of it up in smoke, annihilated by relentless bombing. While many of the inhabitants sought safety deep underground in the ancient Roman aqueducts and tunnels, at least twenty thousand people had been killed.

She tried to envision what it would be like if New York had been similarly decimated, she and her mother out with their shopping bags, stepping over chunks of concrete, going about their day. She couldn’t imagine it. “This is terrible. There’s hardly anything left,” she said.

The driver shrugged. “Naples was the most bombed site in Italy.” “The residents rose up and resisted the Germans, right?” She tried to remember what she’d read in the papers. “Looks like they paid dearly for it.”

“Sure did.” He made a sharp left, off the main road. “They told me to take you directly to the stage.”

She would have thought they’d give her a moment or two to freshen up after her interminable trip. “Is the acting company rehearsing?”

“Nope. It’s a show.” He nodded at the men trudging along the side of the road in the same direction, smoking cigarettes. “This is your audience.” At the sound of a low rumble above them, every helmeted head snapped up, scouring the skies. But it was only thunder, from a slate‑colored cloud to the west, far out over the sea. The helmets snapped back down.

A show. Good. She’d have a chance to watch the other actors. In New York, she’d been given the script for Blithe Spirit, which had been a big hit on Broadway four years earlier, along with instructions to learn the maid’s role, and she had managed to memorize some of the lines during the flight.

The lines were the easy part for Hazel, as she’d been a serial understudy for the past few years. Hazel’s hope, when she first auditioned for the USO, was to be able to break out of her understudy rut and finally act onstage in a real performance. This was her chance to try something new, so that when she returned to New York, she’d be taken seriously as a major actress, not just a backup to be called upon when the leading lady got the flu. Which, with Hazel’s bad luck, had never happened. She’d even established a reputation among producers: Hiring Hazel Ripley as an understudy guaranteed that your leading lady would never miss a show. Twenty plays now under her belt, without going on even once.

Every night, she’d feel a guilty flicker of relief as the star flounced through the stage door, healthy and raring to go, but Hazel attributed her own reticence to her lack of experience. Surely, once she’d gotten a taste of performing in front of an audience, she’d become just as competitive and eager to take center stage as her brother and father had been. She was a Ripley, after all.

Her mother, Ruth, thought that joining the USO tour was a terrible idea, listing off the names of entertainers who had been injured or killed while abroad, usually in plane crashes. “And let’s not forget that pretty Jane Froman, who almost lost both legs when her plane crashed into a river in Portugal,” Ruth had said. “Accidents happen all the time. You know that’s true.”

Hazel had changed the subject fast, recognizing the dangerous quiver in Ruth’s voice. But she remained undeterred. The opportunity to get onstage while supporting her country was too good to pass up, and she viewed it as a way to honor her brother’s memory while, at the same time, stepping out of his shadow. Not to mention the pay was ten dollars a day plus meals. She’d filled out a long questionnaire, had her fingerprints taken, and gotten inoculated for diseases she’d never even heard of. And now, finally, she’d arrived.

The Jeep pulled into an enormous field, where Mount Vesuvius smoked away in the distance. Soldiers had taken seats on long benches facing a truck. One side of the truck bed was folded down to expose a platform furnished with a small table and four chairs; a drab olive canopy was strung overhead. A flag hung from one side, with the words uso camp shows written in blue on a white background. This was the stage, although it couldn’t be more than fifteen feet wide. A few hundred soldiers milled about, chatting and smoking cigarettes, with hundreds more still making their way across the field.

“Over there.” The driver pointed behind the truck, where a large tent had been erected. “That’s where the performers are.” He helped her out and handed her the two suitcases. One held the remaining dastardly uniform and other sundries, while the other was full of her best dresses. The Actors’ Handbook had listed a series of dos and don’ts: For the stage, bring dresses that you’d wear on an important Saturday night date. Travel as a unit at all times. If you behave properly, you’ll increase your chance of making the better tours and improve your living and feeding conditions. Made them sound like livestock, that last one.

“I’d walk you in, but we’re not allowed inside.” The driver’s neck turned red at the very idea. “Good luck.”

“No! Don’t say that.”

The soldier’s eyebrows knitted together with concern. “What?”

“You’re supposed to say, ‘Break a leg.’”

He broke out in a wide smile. “Right. Break a leg.”

Hazel nodded goodbye and slid through the opening in the tent flap backward, awkwardly maneuvering her suitcases inside.

“Well, it’s about time.”

Hazel blinked, her eyes adjusting to the dark interior.

A woman around her age, with hair the color of fire, did a slow turn, the better to show off a curvy figure that oozed out of a green silk dress. Behind her, three women perched on low stools in front of a splintered mirror, applying the final touches of stage makeup.

The redhead’s lip curled. “Hazel Ripley, where the hell have you been?”

At least she knew she was in the right place. “I came straight from the plane.” She shrugged, lifting the suitcases a couple of inches to prove it.

“Get out of that and into something pretty. They just called ten.”

“I’m sorry?”

“They just called ten minutes. That means it’s ten minutes until showtime.” The redhead took a dramatic pause. “Have you ever even acted before? I swear, Jaundiced Jenny is out, and in her place we get Hayseed Hazel.”

The other women giggled.

Hazel stood tall. “I’ve acted before. I know what it means. But I can’t go on.”

“Why not?”

This must be some kind of joke they played on all the newbies. “Because I haven’t rehearsed and don’t know any of the blocking.”

She put down her suitcases and brushed the dust off her skirt, realizing as she did so that it made her seem like a prissy school‑marm. She let her arms fall to her sides.

“You’re the maid. How hard can it be? Do you know your lines?” “I studied them on the plane.”

“Then you’ll be fine. Just enter and exit when you’re supposed to.”

A voice came from outside the tent. “Miss Mead!” “Yes?” the redhead called back.

“Someone to see you.”

She looked at her watch. “Hayseed, get some makeup on and get out of that uniform. See you ladies in the wings.”

Hazel waited a beat. Surely these women would all burst into laughter, now that the joke had been played out, but they just turned back to the mirror.

The redhead seemed familiar. Maybe Hazel had seen her in a show or at an audition back in New York. “Who is that?” she asked.

“That’s Maxine Mead. Our fearless leader.” The speaker, a tall brunette fitted out in a lemon‑yellow dress, stood and shook Hazel’s hand, introducing herself in a deep alto as Verna

“Do we have a leader?” Hazel was still waiting for an acknowledgment of the prank. “I thought we were all second lieutenants.” “Maxine runs the show.”

Verna shrugged and introduced the other two ladies. Phyllis was a rotund milkmaid type with rosy cheeks, and Betty‑Lou was a tiny slip of a girl, perfect for playing kids’ parts, most likely.

“She’s joking, right? About me going on?”

Verna shook her head. “No. We’ve been holding the curtain, waiting for you. You can get ready over there.”

But this was ridiculous. No rehearsal at all? Hazel didn’t even know which actress was playing which character. A lump lodged in her throat at the thought of all those men out there, waiting for the entertainment to begin. This had been a terrible idea. She’d be put on the next plane home, back to doing crosswords in the understudy’s dressing room.

Trembling, Hazel changed into one of her plainer dresses, as befitting a maid, and tied the apron Verna tossed over around her waist. She turned away so the other girls wouldn’t see her hands shaking as she looped the ends into a bow.

After standing in the wings for countless shows, watching others perform, this would be the first time she’d actually step onto the stage? Before thousands of people, with no rehearsal? She yanked the script out of her bag and leafed through the first scene, trying to imprint the cues in her head. The words swam around on the page as her heart pounded in her rib cage.

Another loud clap of thunder. “Will they cancel it if it rains?” “You kidding?” said Phyllis. “Some of these men walked miles to get here. They ain’t going anywhere.”

Hazel followed the other girls behind the big truck. The rain was holding off, but probably not for long, judging from the soggy feel in the air. Hazel longed for a bolt of lightning to hit the truck and cancel the show. Anything to not have to go onstage in front of this sea of men, in a strange country, when she hadn’t eaten or slept in what felt like a week.

She waited in the wings, which was really a small set of stairs that led onstage, forcing back tears. Betty‑Lou handed her a tarnished silver tray. “Here’s your prop.” Hazel couldn’t even whisper anything back—by then, her throat had closed up. She’d wanted desperately to act in a play, but not like this.

Even worse, her character had the first entrance. The lights went up.

She couldn’t go out there. Into the spotlight.

“What are you waiting for?” A solid shove from Maxine, who’d silently reappeared, propelled her up the stairs. Hazel placed the tray on a table downstage as Verna entered from the other side. Hazel had no idea what Verna said, her mind had fuzzed over, but she answered with “Yes’m,” her first line. She managed to utter the next few, hoping she got them in the right order, before scampering like a dog with its tail between its legs back to the safety of the wings.

The soldiers roared with laughter. Backstage, Betty‑Lou gave her a pat on the shoulder. “Not bad.”

The show continued. The other members of the cast were loud and confident, especially Maxine, who was a force of nature as the psychic Madame Arcati. The two male parts were played by men, presumably soldiers who’d volunteered. Each time Hazel ventured out, she relaxed a little more.

When she wasn’t onstage, she watched the eager faces of the soldiers in the first few rows. The men were desperate for entertainment, for something else to think about besides the war, and even when the rain began falling in sheets, no one stirred.

Unfortunately, in spite of the men’s rapt attention, her performance was far from perfect. She stepped on the other girls’ lines instead of waiting her turn to speak, and missed a couple of entrances.

But she’d done it. She’d acted on a stage, in front of people. Terribly, no doubt about that, but as the men whooped and whistled during the curtain call, Hazel managed a proud smile.

“Up and at ’em, ladies.”

Verna’s voice boomed across the pup tent.

Hazel groaned and sat upright. After being driven back to the base the night before, Hazel had skipped dinner and retreated to her assigned cot, the exhaustion from her journey and the sheer terror of performing having caught up with her.

Sure, she’d stunk last night in the show. But what had they expected with no rehearsals?

Better to come clean, try to start fresh. “Listen, everyone. I’m sorry about how awful I was. I didn’t expect to go onstage so soon.”

“Don’t worry about it.” Betty‑Lou’s voice came out a sweet squeak. “We all had a period of adjustment. It’s to be expected.”

“Yeah,” agreed Verna. “The thing about this gig is that you’ll get a do‑over. And another. And another.”

“I’m so sick of Blithe Spirit.” Phyllis yanked a stocking over a thick thigh. Everything about Phyllis was solid and grandmotherly, even though she couldn’t be more than thirty years old. “The men love it, but they love anything. What’s the schedule today?”

Verna looked up at a ragged calendar posted on the bulletin board. “We’re off this morning, then shows at four and eight.”

“I’m serious.” Betty‑Lou put her hands over her face. “I can’t do this play again. Please don’t make me.”

Maybe there was something Hazel could do to make up for last night. She pulled her suitcase out from under her cot and popped it open. Digging through the dresses, she found the book she was looking for and held it up.

“I brought this with me. Twelve Best American Plays from 1936 to 1937. Maybe one of these will work instead.”

Betty‑Lou let out a shriek. “Amen! I thought we’d be waiting another month for a new script. Now we have twelve. Maxine,look.”

Maxine, who’d been uncharacteristically subdued, reading a book on her cot, swung her legs over the side. “Let’s see.”

Hazel tossed it over.

“Not bad.” Maxine thumbed through it. “We can work with this. Good job, Hayseed.”

Hazel refused to let that nickname stick. “Look, I really don’t want to be called Hayseed during my tour. I’ve paid my dues.”

“In what way?”

“Well, I’ve worked on Broadway since 1939.”

Maxine studied her. “Why don’t I remember you, then? When I lived in New York, I went to everything.”

“I was an understudy.” “Huh. Did you ever go on?” Hazel swallowed. “No.”

“Wait a minute.” Verna snapped her fingers. “I heard about you. Didn’t you understudy for something like two dozen shows and never once perform?” She didn’t wait for an answer. Not that Hazel wanted to give her one. “That’s right! The producers loved you because the audiences were never disappointed. It was in the Post.” Hazel’s mother had read the article aloud the day it came out, while Hazel’s ears burned with embarrassment. “What a shame,” Ruth had said. “You standing in the sidelines while real actresses like Fay Wray and Betty Furness get the spotlight.

Seriously, Hazel. Your brother would’ve been very disappointed.”

A man’s voice called out from the other side of the tent’s flap door. “The facilities are ready for you, ladies.”

Hazel, relieved by the interruption, followed the girls outside, clutching her helmet and a towel. They were led to the washing area, where a board with circular cutouts lay across two wooden horses. The women stuck their helmets under the faucet and filled them with water before laying them in the holes, a kind of make‑ shift sink. Hazel washed her face and hands and brushed her teeth before dumping out the water and wiping the inside of her helmet with a towel.

She’d hoped that she’d have the morning to get her bearings around the camp but instead was told to report back to Naples to fill out more paperwork, with Maxine assigned to accompany her. She wished it had been one of the others.

Hazel held tight as the Jeep careened back toward Naples over roads that were no better than those in the Dark Ages must have been. Above the narrow streets, laundry hung limply from precarious‑looking balconies. They took a right, coming to a small plaza, where a crowd blocked the way.

“What’s going on?” asked Maxine.

The driver stood up to get a better look. “Stay here, in the Jeep.”

He climbed out and was soon swallowed by the crowd.

Hazel and Maxine pulled themselves up to standing to get a better view. The focal point of attention seemed to be a beautiful, very pale boy with full cheeks, his blond hair swept off to one side. For a moment, Hazel almost called out her brother’s name. The resemblance was uncanny: Even the way the boy tossed his head to get his hair out of his eyes was the same. When her brother used to do that, girls swooned.

But no, it wasn’t Ben. This kid was too young, for one, and when he turned his head, the profile wasn’t quite right, the nose slightly turned up at the tip. He had one arm flung around a slightly older boy sporting the beginnings of a mustache, who seemed to be near tears.

The swarm pushed in, jostling the boys closer together. The blond boy looked defiant, his light complexion a stark contrast to that of his olive‑skinned companion.

A rock flew out of nowhere and struck the blond in the forehead. He winced but didn’t speak or cry out. A shock of red blood oozed out just below his hairline.

Hazel gasped, shielding the sun with her hand for a better view of the scene. “Why are they attacking them?”

An old Italian woman standing next to the Jeep, her head covered by a green paisley scarf, answered in broken English. “They were caught trying to steal bicycles. One refuses to speak. Probably a German, the other a collaboratore.”

“Jesus,” said Maxine. “What will happen to them?”

“They die.” The woman spit on the ground before allowing herself to be sucked forward with the surge of the mob like liquid mercury.

Hazel tried to spot their driver. He’d made it about halfway to the boys, but the pack had tightened and wasn’t responding to his commands to step aside. Hazel pointed to a group of kids who were collecting rocks from the rubble of a bombed‑out wall.

“They’re going to stone them to death!”

This primitive system of justice outraged Hazel, but the energy emanating from the crowd was like a living, breathing monster, unstoppable. The blond boy seemed resigned to his fate, but held on tightly to his friend as others tried to pull them apart. The dark‑haired one shook his head, tears streaming down his face, as a man near the edge of the crowd lifted an enormous cement block above his head and, staggering under its weight, headed in the direction of the boys.

In one swift motion, Maxine climbed over to the front seat of the Jeep and slid behind the wheel. She laid hard on the horn, shifted the gears, and gunned the engine.

Hazel clutched the side of the Jeep and stifled a scream as Maxine drove forward. This was madness, driving straight into danger. Distracted by the horn, the crowd parted, some of them barely stepping out of the way in time.

Their driver, who’d finally made it to the boys, looked up and spotted the vehicle. The look of relief on his face was quickly replaced by an angry snarl directed at the Neapolitans around him. He grabbed both boys by the scruff of their jackets, like a couple of puppies, and yanked them in the direction of the Jeep. As Maxine tumbled back into the rear seat, revealing a flash of pale upper thigh, a man standing at Hazel’s elbow said something in Italian and tried to reach inside. Hazel swatted him off and gave him a good thunk on the forehead with the meat of her palm for good measure. Finally, the driver got close enough to shove the dark‑ haired boy into the front passenger seat and the blond one next to them in the back, before taking the wheel.

He reversed up the street to a crossing, executed a quick turn, and sped away. Hazel breathed in great gulps of air, thankful to be free, as the dark‑haired boy sobbed into his hands. The blond one, grimacing, allowed Maxine to dab at his forehead with a handkerchief.

Maxine said something quietly, under her breath, and the boy, eyes wide, responded in kind. In German. The suspicions of the crowd had been correct.

Hazel leaned over. “You speak German?”

Maxine addressed Hazel without taking her eyes off the boy. “My grandmother is German. I learned some from her.”

No one with German or Italian parents was allowed to audition for the USO tour. Hazel supposed grandparents were all right, although she doubted Maxine would have been crazy enough to volunteer that information.

Hazel noticed the driver watching them closely in the rearview mirror. The rest of the ride, the boy spoke fast and furiously, Maxine interrupting every so often to ask a question.

“What is he saying?” Hazel couldn’t wait any longer.

Maxine spoke loudly, so the driver could hear as well. “His name is Paul, his father was a senior colonel in the German army, who sent for him and his mother to join him in Calabria early in the war. I don’t think the woman was married to him, more of a mistress. Paul befriended this Italian boy—Matteo, he’s called— and says they both worked with the Italian resistance, against the Germans.”

“Against his own father?” Hazel glanced ahead at the driver, who remained stone‑faced.

“That’s what Paul says. He and his mother were left behind, abandoned by his father when the German army retreated. His mother was killed soon after. Paul went into hiding, protected by his friend’s family.”

The German boy addressed Maxine again. She nodded. “He says he can prove that he was part of the resistance, if they reach out to Matteo’s father.”

Matteo nodded. “Mio padre, in Calabria.”

“What are they doing here in Naples?” Hazel asked.

“It was becoming too dangerous in the countryside, Matteo’s family was threatened, so the two boys ran off to try to make it to the Americans in Naples. The idea was for Paul to turn himself in and explain his story. They stole bikes and traveled by night. Until they got caught.”

They pulled up at a large square called the Piazza Municipio, ringed on three sides by official‑looking buildings in a deep ocher. If their story were true, the boys had made it to safety, just barely. But Hazel had a suspicion that they weren’t in the clear just yet, as did they, judging from their terrified faces.

Maxine addressed the driver. “What happens to them now?” “I’ll take care of them. You go up this way.” The driver nodded toward an arched doorway. “Through there.”

The German boy grabbed Maxine’s arm and rattled off something fast.

“He says he’s only fifteen, that he never hurt anyone.”

The driver gave her a dark look. “He’s a prisoner. Not a pet.” They had no choice but to watch as the boys were driven off, but Maxine and the German boy locked eyes until the Jeep rounded the corner and disappeared.

Inside, Hazel filled out her paperwork in triplicate while Maxine explained to the major in charge what had happened, trying to convince him to look further into the situation.

“The German one, Paul, says he was brought here when he was just eleven,” said Maxine, “and that he can prove that he’s been part of the resistance if you reach out to the father of the other boy.” The major barely contained the scorn in his voice. “What makes you think you can trust some German kid, take his words at face value? He’s just trying to save his hide. Probably a regular soldier who got stuck behind enemy lines. They’ll say anything to stay alive.”

“He’s too young to have been a soldier. After all, the Germans retreated two years ago. Will you at least look into his story?”

Maxine’s bravery in the square, as well as now, with the major, astonished Hazel. She wished she were that brash. But she wouldn’t dare question an authority figure. Always the understudy, in life as well as in art. The thought smarted.

The major didn’t answer Maxine’s question. “You said you spoke German to him?”

Maxine responded with a barely perceptible nod. “My grandmother is German. But she’s lived in America forever. She has nothing to do with the old country.”

“Huh. Don’t go anywhere. I have to check something.” He disappeared into a back room.

Hazel looked over at Maxine, whose face had turned white. “Are you all right?”

“Let’s hope they don’t haul me off, too.” She laughed but it didn’t reach her eyes. “I couldn’t help it. They were so young. Just boys.” The haunted look on Maxine’s face stirred Hazel’s memory.

She’d seen a woman on her brother’s arm wearing a similar expression, years ago. That must be why Maxine looked so familiar: Her brother had dated a striking redhead for a couple of months, whom Hazel had met only briefly. The realization almost knocked the wind out of her.

“Did you know my brother back in New York?” The more she studied Maxine, the more convinced she became. “You did, I’m sure of it. I saw you with him. A couple of times.”

“What on earth are you talking about?” The color had crept back into Maxine’s face, and her usual look of annoyance had returned.

“My brother was named Ben Ripley. I’m sure I remember him introducing you around to his gang at a coffee shop downtown, his friends joking that you were way above his pay grade. And another time, when we were all at a demonstration in New York.

Something against fascism, I’m pretty sure. Or maybe against the Spanish War. There were so many protests back then.” Along with her brother and all of their friends, Hazel had marched practically every weekend, signed every petition. Anything to stop the wave of authoritarianism sweeping the world. Ben had shown up to one rally with the exotic‑looking redhead. The crowd had been rowdy, and after a short while, the girl had yanked Ben away. Hazel hadn’t seen her since.

Maxine cocked her head. “I dated a guy named Ben, an actor, for a New York minute. You’re his sister?”

“I am. I knew it! That’s where I know you from. It’s been bugging me since I arrived.”

For a moment the boys in the square were forgotten. Maxine let out a bark of a laugh. “Ben Ripley. Sure thing. I thought we were going out for a picnic in the park, but the guy dragged me to some demonstration. I couldn’t get out of there fast enough. He was way too full of himself for me. Still is, I’m guessing?”

Hazel wasn’t sure how to respond. She shook her head. Even though it had been three years, the words never came out right.

“No. Not anymore.”

The Chelsea Girls

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction, Women's Fiction

- hardcover: 368 pages

- Publisher: Dutton

- ISBN-10: 1524744581

- ISBN-13: 9781524744588