Excerpt

Excerpt

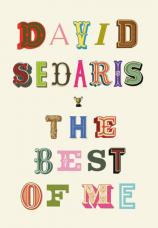

The Best of Me

Introduction

I’m not the sort of person who goes around feeling good about himself. I have my days, don’t get me wrong, but any confidence I possess, especially in regard to my writing, was planted and nurtured by someone else—first a teacher, then later an agent or editor. “Hey,” he or she would say, “this is pretty good.”

“Really?” This was my cheap way of getting them to say it again. “You’re not just telling me that because you feel sorry for me?”

“Yes…I mean, no. I really like it!”

Still, I never quite believed them.

What lifted me up was writing for The New Yorker. While this had always been a fantasy of mine, I did nothing to nudge it along. I’d always heard that if the magazine wanted you, they’d find you, and that’s exactly what happened. I started my relationship with them in 1995, when an editor phoned and asked if I might write a Shouts & Murmurs piece on then-president Bill Clinton’s welfare reform proposal. I was given one day to complete it, and when I was told that it would run in the next week’s issue, something inside me changed. It wasn’t seismic, like an earthquake, but more like a medium-size boulder that had shifted a little. Nevertheless, I felt it. When the magazine came out, I opened it to my piece, arranged it just so on the kitchen table, and strolled past it, wanting my younger, twenty-year-old self to see his name at the top of the page.

“Wait a minute.…Is that…me? In The New Yorker?” Thirty-nine years it had taken the magazine to notice me. Good thing I wasn’t in any rush.

If you read an essay in Esquire and don’t like it, there could be something wrong with the essay. If it’s in The New Yorker, on the other hand, and you don’t like it, there’s something wrong with you. That said, you’re never going to please everyone. It’s hard to think of a single entry in this book that didn’t generate a complaint of one sort or another. And it could be anything—“How dare you suggest French dentists are better than American ones!” “What sort of monster won’t swap seats on a plane?” Many were angry that I’d inadvertently killed a couple of sea turtles. Granted, that was bad, but I was a child at the time, and don’t you have to eventually forgive someone for what he did when he was twelve?

There is literally nothing you can print anymore that isn’t going to generate a negative response. This, I believe, was brought on by the Internet. It used to be that you’d write a letter of complaint, then read it over, wondering, Is this really worth a twenty-five-cent stamp? With the advent of email, complaining became free. Thus, people who were maybe a tiny bit offended could, at no cost whatsoever, let you know that they were NEVER GOING TO BUY ANY OF YOUR BOOKS EVER AGAIN!!!!

They always take the scorched-earth policy for some reason. Of all the entries in this book, the one that generated the most anger was “The Motherless Bear.” Oh, the mail I got. “How dare you torture animals like this!”

“It’s a fictional story,” I wrote back to everyone who complained. “The giveaway is that the title character speaks English and feels sorry for herself. Bears don’t do that in real life.”

That wasn’t enough for a woman in England. “I urge you not to mock these intelligent and sentient creatures,” she wrote, demanding that I atone by involving myself with the two bear-rescue organizations she listed at the bottom of her letter.

Just as we can never really tell what our own breath smells like, I will never know if I would like my writing. If I wasn’t myself, and someone sent me one of my essay collections, would I recommend it to friends? Would I stop reading it after a dozen or so pages? There’s so much that goes into a decision like that. How many times have I dismissed something just because a person I didn’t approve of found it enjoyable? Or maybe I decided it was too popular. That’s the sort of snobbery that kept my younger self slogging through books I honestly had no interest in, the sorts I’d announce had taken me “six months to finish” but were only two hundred pages long. If something is written in your native language and it’s taking you half a year to get through it, unless you’re being paid by the hour to read it, I’d say there’s a problem.

One thing that I would like about my writing is that so much of it has to do with family. It’s something that’s always interested me and is one of the reasons I so love Greeks. You could meet an American and wait for months before he begins a sentence with the words “So then my mother…” It’s the same in France and England. Oh, they might get around to it eventually, but it never feels imperative. With Greeks, though, it’s usually only a matter of seconds before you hear about someone’s brother, or what a pain his sister is.

There’s a lot of talk lately about “the family you choose.” It’s a phrase often used by people who were rejected by their parents or siblings and so formed a group of supportive, kindred spirits. I think it’s great they’re part of a tight-knit circle, but I wouldn’t call it a family. Essential to that word is that the people you’re surrounded by were not chosen. They were assigned by fate, and now you must deal with them in one way or another until you die. For me, that hasn’t been much of a problem. Even when I was a teenager, I wouldn’t have traded my parents for anyone else’s, and the same goes for my brother and sisters.

It bothers me, then, when someone refers to my family as “dysfunctional.” That word is overused, at least in the United States, and, more to the point, it’s wrongly used. My father hoarding food inside my sister’s vagina would be dysfunctional. His hoarding it beneath the bathroom sink, as he is wont to do, is, at best, quirky and at worst unsanitary.

There’s an Allan Gurganus quote I think of quite often: “Without much accuracy, with strangely little love at all, your family will decide for you exactly who you are, and they’ll keep nudging, coaxing, poking you until you’ve changed into that very simple shape.”

Is there a richer or more complex story than that?

I like to think that the affection I have for my family is apparent. Well into our adulthoods—teetering on our dotage, most of us—we’re still on good terms. We write one another, we talk. We take vacations together. I just can’t see the dysfunction in that.

The pieces in this book—both fiction and nonfiction—are the sort I hoped to produce back when I first started writing, at the age of twenty. I didn’t know how to get from where I was then to where I am now, but who does? Like everyone else, I stumbled along, making mistakes while embarrassing myself and others (sorry, everyone I’ve ever met). I’ll always be inclined toward my most recent work, if only because I’ve had less time to turn on it. When I first started writing essays, they were about big, dramatic events, the sort you relate when you meet someone new and are trying to explain to them what made you the person you are. As I get older, I find myself writing about smaller and smaller things. As an exercise it’s much more difficult, and thus—for me, anyway—much more rewarding. I hope you feel the same. If not, I can probably expect to hear from you.

Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter

Vol. 3, No. 2

Dear Subscriber,

First of all, I’d like to apologize for the lack of both the spring and summer issues of Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter. I understand that you subscribed with the promise that this was to be a quarterly publication—four seasons’ worth of news from the front lines of our constant battle against oppression. That was my plan. It’s just that last spring and summer were so overwhelming that I, Glen, just couldn’t deal with it all.

I’m hoping you’ll understand. Please accept as consolation the fact that this issue is almost twice as long as the others. Keep in mind the fact that it’s not easy to work forty hours a week and produce a quarterly publication. Also, while I’m at it, I’d like to mention that it would be wonderful if everyone who read Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter also subscribed to Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter. It seems that many of you are very generous when it comes to lending issues to your friends and family. That is all well and good as everyone should understand the passion with which we as a people are hated beyond belief. But at the same time, it costs to put out a newsletter and every dollar helps. It costs to gather data, to Xerox, to staple and mail, let alone the cost of my personal time and energies. So if you don’t mind, I’d rather you mention Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter to everyone you know but tell them they’ll have to subscribe for themselves if they want the whole story. Thank you for understanding.

As I stated before, last spring and summer were very difficult for me. In late April Steve Dolger and I broke up and went our separate ways. Steve Dolger (see newsletters volume 2, nos. 1–4 and volume 3, no. 1) turned out to be the most homophobic homosexual I’ve ever had the displeasure of knowing. He lives in constant fear, afraid to make any kind of mature emotional commitment, afraid of growing old and losing what’s left of his hair, and afraid to file his state and federal income taxes (which he has not done since 1987). Someday, perhaps someday very soon, Steve Dolger’s past will come back to haunt him. We’ll see how Steve and his little seventeen-year-old boyfriend feel when it happens!

Steve was very devious and cold during our breakup. I felt the chill of him well through the spring and late months of summer. With deep feelings come deep consequences and I, Glen, spent the last two seasons of my life in what I can only describe as a waking coma—blind to the world around me, deaf to the cries of suffering others, mutely unable to express the stirrings of my wildly shifting emotions.

I just came out of it last Thursday.

What has Glen discovered? I have discovered that living blind to the world around you has its drawbacks but, strangely, it also has its rewards. While I was cut off from the joys of, say, good food and laughter, I was also blind to the overwhelming homophobia that is our everlasting cross to bear.

I thought that for this edition of the newsletter I might write something along the lines of a homophobia Week in Review but this single week has been much too much for me. Rather, I will recount a single day.

My day of victimization began at 7:15 A.M. when I held the telephone receiver to my ear and heard Drew Pierson’s voice shouting, “Fag, Fag, Fag,” over and over and over again. It rings in my ears still. “Fag! I’ll kick your ass good and hard the next time I see you. Goddamn you, Fag!” You, reader, are probably asking yourself, “Who is this Drew Pierson and why is he being so homophobic toward Glen?”

It all began last Thursday. I stopped into Dave’s Kwik Stop on my way home from work and couldn’t help but notice the cashier, a bulky, shorthaired boy who had “athletic scholarship” written all over his broad, dullish face and “Drew Pierson: I’m here to help!” written on a name tag pinned to his massive chest. I took a handbasket and bought, I believe, a bag of charcoal briquettes and a quartered fryer. At the register this Drew fellow rang up the items and said, “I’ll bet you’re going home to grill you some chicken.”

I admitted that it was indeed my plan. Drew struck me as being very perceptive and friendly. Most of the Kwik Stop employees are homophobic but something about Drew’s manner led me to believe that he was different, sensitive and open. That evening, sitting on my patio and staring into the glowing embers nestled in my tiny grill, I thought of Drew Pierson and for the first time in months I felt something akin to a beacon of hope flashing through the darkness of my mind. I, Glen, smiled.

I returned to Dave’s Kwik Stop the next evening and bought some luncheon meat, a loaf of bread, potato chips, and a roll of toilet paper.

At the cash register Drew rang up my items and said, “I’ll bet you’re going on a picnic in the woods!”

The next evening I had plans to eat dinner at the condominium of my sister and her homophobic husband, Vince Covington (see newsletter volume 1, no. 1). On the way to their home I stopped at the Kwik Stop, where I bought a can of snuff. I don’t use snuff, wouldn’t think of it. I only ordered snuff because it was one of the few items behind the counter and on a lower shelf. Drew, as an employee, is forced to wear an awkward garment—sort of a cross between a vest and a sandwich board. The terrible, synthetic thing ties at the sides and falls practically to the middle of his thigh. I only ordered the snuff so that, as he bent over to fetch it, I might get a more enlightened view of Drew’s physique. Regular readers of this newsletter will understand what I am talking about. Drew bent over and squatted on his heels, saying, “Which one? Tuberose? I used to like me some snuff. I’ll bet you’re going home to relax with some snuff, aren’t you?”

The next evening, when I returned for more snuff, Drew explained that he was a freshman student at Carteret County Community College, where he majors in psychology. I was touched by his naïveté. CCCC might as well print their diplomas on tar paper. One might take a course in diesel mechanics or pipe fitting but under no circumstances should one study psychology at CCCC. That is where certified universities recruit their studies for abnormal psychology. CCCC is where the missing links brood and stumble and swing from the outer branches of our educational system.

Drew, bent over, said that he was currently taking a course in dreams. The teacher demands that each student keep a dream notebook, but Drew, exhausted after work, sleeps, he said, “like a gin-soaked log,” and wakes remembering nothing.

I told him I’ve had some interesting dreams lately, because it’s true, I have.

Drew said, “Symbolic dreams? Dreams that you could turn around when you’re awake and make sense of?”

I said, yes, haunting dreams, meaningful, dense.

He asked then, hunkered down before the snuff, if I would relate my dreams to him. I answered, yes indeed, and he slapped a tin of snuff on the counter and said, “On the house!”

I returned home, my heart a bright balloon. Drew might be young, certainly—perhaps no older than, say, Steve Dolger’s current boyfriend. He may not be able to hold his own during strenuous intellectual debate, but neither can most people. My buoyant spirit carried me home, where it was immediately deflated by the painful reminder that my evening meal was to consist of an ethnic lasagna pathetically submitted earlier that day by Melinda Delvecchio, a lingering temp haunting the secretarial pool over at the office in which I work. Melinda, stout, inquisitive, and bearded as a pot-bellied pig, has taken quite a shine to me. She is clearly and mistakenly in love with me and presents me, several times a week, with hideous dishes protected with foil. “Someone needs to fatten you up,” she says, placing her eager hooves against my stomach. One would think that Melinda Delvecchio’s kindness might come as a relief to the grinding homophobia I encounter at the office.

One might think that Melinda Delvecchio is thoughtful and generous until they pull back the gleaming foil under which lies her hateful concoction of overcooked pasta stuffed with the synthetic downy fluff used to fill plush toys and cheap cushions. Melinda Delvecchio is no friend of mine—far from it—and, regarding the heated “lasagna” steaming before me, I made a mental note to have her fired as soon as possible.

That night I dreamt that I was forced to leave my home and move underground into a dark, subterranean chamber with low, muddy ceilings and no furniture. That was bad enough, but to make matters worse I did not live alone but had to share the place with a community of honest-to-God trolls. These were small trolls with full beards and pointy, curled shoes. The trolls were hideously and relentlessly merry. They called me by name, saying, “Glen, so glad you could join us! Look, everybody, Glen’s here! Welcome aboard, friend!” They were all so agreeable and satisfied with my company that I woke up sweating at 6:00 A.M. and could not return to sleep for fear of them.

I showered twice and shaved my face, passing the time until seven, at which time I phoned Drew at his parents’ home. He answered groggy and confused. I identified myself and paused while he went to fetch a pencil and tablet with which to record my story.

Regular readers of Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter know that I, Glen, honor truth and hold it above all other things. The truth, be it ugly or naked, does not frighten me. The meaner the truth, the harder I, Glen, stare it down. However, on this occasion I decided to make an exception. My dreaming of trolls means absolutely nothing. It’s something that came to me in my sleep and is of no real importance. It is our waking dreams, our daydreams that are illuminating. Regular readers of Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter know that I dream of the day when our people can walk the face of this earth free of the terrible homophobia that binds us. What are sleeping dreams but so much garbage? I can’t bear to hear other people’s dreams unless I myself am in them.

I put all these ideas together in a manageable sort of way and told Drew Pierson that I dreamt I was walking through a forest of angry, vindictive trees.

“Like those hateful trees in The Wizard of Oz?” he said. “Those mean trees that threw the apples?”

“Yes,” I said, “exactly.”

“Did any of them hit you?” he asked, concerned.

“A few.”

“Ouch! Then what?”

I told him I came upon a clearing where I saw a single tree, younger than the rest but stocky, a husky, good-looking tree that spoke to me, saying, “I’ll bet you’re tired of being hated, aren’t you?”

I could hear Drew scratching away with his pencil and repeating my dictation: “I…bet…you’re…tired…of…being…hated…”

I told Drew that the tree had spoken in a voice exactly like his own, low and firm, yet open and friendly.

“Like my voice, really?” He seemed pleased. “Damn, my voice on a tree. I never thought about a thing like that.”

That night I dreamt I was nailed to a cross that was decorated here and there with fragrant tulips. I glanced over at the cross next to me, expecting to see Christ, but instead, nailed there, I saw Don Rickles. We waved to each other and he mouthed the words, “Hang in there.”

I called Drew the next morning and told him I once again dreamt I was in a forest clearing. Once again I found myself face-to-face with a husky tree.

Drew asked, “What did the tree say this time?”

I told him the tree said, “Let me out! Let me out! I’m yearning to break free.”

“Break free of what?” he asked.

“Chains and limitations,” I said. The tree said, “Strip me of my bark, strip me of my bark.”

“The tree said that to you personally or was there someone else standing around?”

I told him the tree spoke to me personally and that I had no choice but to do as I was told. I peeled away the bark with my bare hands and out stepped Drew, naked and unashamed.

“Naked in the woods? I was in the woods naked like that? Then what?”

I told Drew I couldn’t quite remember what happened next; it was right on the tip of my mind where I couldn’t quite grasp it.

Drew said, “I want to know what I was doing naked in the woods is what I want to know.”

I said, “Are you naked now?”

“Now?” Drew, apparently uncertain, took a moment before saying, “No. I got my underwear on.”

I suggested that if he put the telephone receiver into the pouch of his briefs it might trigger something that would help me recall the rest of my dream.

I heard the phone muffle. When I yelled, “Did you put the phone where I told you to?” I heard a tiny, far-off voice say, “Yes, I sure did. It’s there now.”

“Jump up and down,” I yelled. “Jump.”

I heard shifting sounds as Drew’s end of the telephone jounced around in his briefs. I heard him yell, “Are you remembering yet?” And then, in the distance, I heard a woman’s voice screaming, “Drew Pierson, what in the name of God are you doing with that telephone? Other people have to put their mouth on that thing too, you know. You should be strung up for doing a thing like that, goddamn you.” I heard Drew say that he was doing it in order to help someone remember a dream. Then I heard the words “moron,” “shit for brains,” and the inevitable “fag.” As in “Some fag put you up to this, didn’t he? Goddamn you.”

Then Drew must have taken the receiver out of his briefs because suddenly I could hear him loud and clear and what I heard was homophobia at its worst. “Fag! Fag! I’ll kick your ass good and hard the next time I see you. Goddamn you to hell.” The words still echo in my mind.

I urge all my readers to BOYCOTT DAVE’S KWIK STOP. I urge you to phone Drew Pierson anytime day or night and tell him you dreamt you were sitting on his face. Drew Pierson’s home (ophobic) telephone number is 787-5008. Call him and raise your voice against homophobia!

So that, in a nutshell, was my morning. I pulled myself together and subjected myself to the daily homophobia convention that passes as my job. Once there, I was scolded by my devious and homophobic department head for accidentally shredding some sort of disputed contract. Later that afternoon I was confronted, once again, by that casserole-wielding mastodon, Melinda Delvecchio, who grew tearful when informed that I would sooner dine on carpet remnants than another of her foil-covered ethnic slurs.

On my way home from the office I made the mistake of stopping at the Food Carnival, where I had no choice but to park in one of the so-called “handicapped” spaces. Once inside the store I had a tiff with the homophobic butcher over the dictionary definition of the word cutlet. I was completely ignored by the homophobic chimpanzee they’ve hired to run the produce department and I don’t even want to talk about the cashier. After collecting my groceries I returned to the parking lot, where I encountered a homophobe in a wheelchair, relentlessly bashing my car again and again with the foot pedals of his little chariot. Regular readers of Glen’s Homophobia Newsletter know that I, Glen, am not a violent man. Far from it. But in this case I had no choice but to make an exception. My daily homophobia quota had been exceeded and I, Glen, struck back with brute physical force.

Did it look good? No, it did not.

But I urge you, reader, to understand. Understand my position as it is your own.

Understand and subscribe, subscribe.

Front Row Center

with Thaddeus Bristol

Trite Christmas: Scottsfield’s young hams offer the blandest of holiday fare

The approach of Christmas signifies three things: bad movies, unforgivable television, and even worse theater. I’m talking bone-crushing theater, the type our ancient ancestors used to oppress their enemies before the invention of the stretching rack. We’re talking torture on a par with the Scottsfield Dinner Theater’s 1994 revival of Come Blow Your Horn, a production that violated every tenet of the Human Rights Accord. To those of you who enjoy the comfort of a nice set of thumbscrews, allow me to recommend either of the crucifying holiday plays and pageants currently eliciting screams of mercy from within the confines of our local elementary and middle schools. I will, no doubt, be taken to task for criticizing the work of children but, as any pathologist will agree, if there’s a cancer it’s best to treat it as early as possible.

The Best of Me

- Genres: Essays, Fiction, Humor, Nonfiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316242403

- ISBN-13: 9780316242400