Excerpt

Excerpt

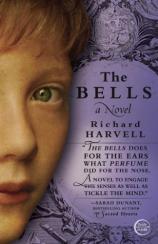

The Bells

First, there were the bells. Three of them, cast from warped shovels, rakes, and hoes, cracked cauldrons, dulled ploughshares, one rusted stove, and, melted into each, a single golden coin. They were rough and black except along their silvery lips, where my mother's mallets had struck a million strokes. She was small enough to dance beneath them in the belfry. When she swung, her feet leapt from the polished wooden planks, so that when the mallet met the bell, it rang from the bell's crown to the tips of my mother's pointed toes.

They were the Loudest Bells on Earth, all the Urners said, and though now I know a louder one, their place high above the Uri Valley made them very loud indeed. The peal could be heard from the waters of Lake Lucerne to the snows of the Gotthard Pass. The ringing greeted traders come from Italy. Columns of Swiss soldiers pressed their palms against their ears as they marched the Uri Road. When the bells began to sound, teams of oxen refused to move. Even the fattest men lost the urge to eat, from the quivering of their bowels. The cows that grazed the nearby pastures were all long since deaf. Even the youngest herders had the dull ears of old men, though they hid in their huts morning, noon, and night when my mother rang her bells.

I was born in that belfry, above the tiny church. There I was nursed. When it was warm enough, there we slept. Whenever my mother did not swing her mallets, we huddled beneath the bells, the four walls of the belfry open to the world. She sheltered me from the wind and stroked my brow. Though she never spoke a word to me, nor I to her, she watched my mouth as I babbled infant sounds. She tickled me so I would laugh. When I learned to crawl, she held my foot so I did not creep off the edge and fall to my death on the jutting rocks below. She helped me stand. I held a finger in each fist, and she led me round and round, past each edge a hundred times a day. In terms of space, our belfry was a tiny world --- most would have thought it a prison for a child. But in terms of sound, it was the most massive home on earth. For every sound ever made was trapped in the metal of those bells, and the instant my mother struck them, she released their beauty to the world. So many ears heard the thunderous pealing echo through the mountains. They hated it; or were inspired by its might; or were entranced until they stared blindly into space; or cried as the vibrations shook their sadness out. But they did not fi nd it beautiful. They could not. The beauty of the pealing was reserved for my mother, and for me, alone.

I wish that were the beginning: my mother and those bells, the Eve and Adam of my voice, my joys, and my sorrows. But of course that is not true. I have a father; my mother had one as well. And the bells, too; they had a father. Theirs was Richard Kilchmar, who, one night in 1725, tottered on a table, so drunk he saw two moons instead of one.

He shut one eye and squished the other so the two moons resolved into a single fuzzy orb. He looked about: Two hundred men filled Altdorf's square, in a town that was, and was proud to be, at the very center of the Swiss Confederation. These men were celebrating the harvest, and the coronation of the new pope, and the warm summer night. Two hundred men ankle- deep in piss- soaked mud. Two hundred men with mugs of acrid Schnapps burned from Uri pears. Two hundred men as drunk as Richard Kilchmar.

"Quiet!" he yelled into the night, which seemed as warm and clear to him as the thoughts within his head. "I will speak!"

"Speak!" they yelled.

They were quiet. High above, the Alps shone in the moonlight like teeth in black, rotting gums.

"Protestants are dogs!" he yelled, raised his mug, and nearly stumbled off the table. They cheered and cursed the dogs in Zurich, who were rich. They cursed the dogs in Bern, who had guns and an army that could climb the mountains and conquer Uri if they wished. They cursed the dogs in German lands farther north, who had never heard of Uri. They cursed the dogs for hating music, for defaming Mary, for wishing to rewrite the Holy Book.

These curses, two hundred years dull in the capitals of Europe, pierced Kilchmar's heart. They brought tears to his eyes --- these men before him were his brothers! But what could he reply? What could he promise them? So little. He could not build them a fort with cannons. He was one of Uri's richest men, but still, he could not afford an army. He could not soothe them with his wisdom, for he was not a man of words.

Then they all heard it, the answer to his silent plea. A ringing that made them raise their bleary eyes toward heaven. Someone had climbed the church's belfry and tolled the church's bell. It was the most beautiful, heartaching sound Richard Kilchmar had ever heard. It resounded off the houses. It echoed off the mountains. The peal tickled his swollen belly. When the ringing ceased, the silence was as warm and wet as the tears Kilchmar rubbed from out his eyes. He nodded at the crowd. Two hundred heads nodded back at him.

"I will give you bells," he whispered. He sloshed his drink at the midnight sky. His voice rose to a shout. "I will build a church to house them, high up in the mountains, so the ringing echoes to every inch of Uri soil! They will be the Loudest and Most Beautiful Bells Ever!"

They cheered even more loudly now than they had before. He raised his arms in triumph. Schnapps washed his brow. Then he and every man plunged their eyes into the bottom of their mugs and drank them empty, sealing Kilchmar's pledge.

As he drank the fi nal drop, Kilchmar stumbled back, tripped, and fell. He spent the rest of the night lying in the mud, dreaming of his bells.

He awoke to a circle of blue sky ringed by twenty reverent faces.

"Lead us!" they implored him.

Their veneration seemed to lift him to his feet, and after six or eight swigs from their fl asks, he felt more weightless still. Soon he found himself on his horse leading a pro cession: fifty horses; several carts filled with women; children and dogs darting through the grasses. Where to lead them he did not know, for until that day he'd found the mountains menacing and hostile. But now he led them up the Uri Road toward Italy, toward the pope, toward snowfields glittering in the sun, and then, when inspiration took him, turned off and began to climb.

Up and up they went, almost to the cliffs and snow. Kilchmar now led five hundred Urners, and they followed him until they reached a rocky promontory and beheld the valley stretched before them, the river Reuss a thin white thread stitching it together.

"Here," he whispered. "Here."

"Here," they echoed. "Here."

They turned then to regard the tiny village just below them, a mere jumble of squalid houses. The villagers and their scrawny cows stared back in awe at the assemblage on the rocky hill. This tiny, starved village I write of is Nebelmatt. In this village I was born (may it burn to the ground and be covered by an avalanche).

Kilchmar's church was completed in 1727, built of only Uri sweat and Uri stone, so that, in the winter months, no matter how much wood was wasted in the stove, the church remained as cold as the mountain upon which it was built. It was a stocky church, shaped something like a boot. The bishop was petitioned for a priest well suited to the frigid and lonesome aspects of the post. His reply came a few days later in the form of a young priest scowling at Kilchmar's door --- a learned father Karl Victor Vonderach. "Just the man," read the bishop's letter, "for a posting on a cold, distant mountain. Do not send him back."

Now the church had a master, twelve rustic pews, and a roof that kept out a good deal of the rain, but it still did not have what Kilchmar had promised them. It did not have its bells. And so Kilchmar packed his cart, kissed his wife, and said he would undertake an expedition to St. Gall to find the greatest bell maker in the Catholic world. He rumbled off northward to patriotic cries, and was never seen in Uri again.

The building of the church had ruined him. And so, one year after the last slate had been laid on its roof, the church built to house the Loudest and Most Beautiful Bells Ever did not even have a cowbell hanging in its belfry.

Urners are a proud and resourceful folk. How hard can it be to make a bell? they thought. Clay molds, some molten metal, some beams on which to hang the finished bells --- nothing more. Perhaps God had sent them Kilchmar only to set them on their way.

God needs your iron, went the call. Bring Him your copper and your tin.

Rusted shovels, broken hoes, corroded knives, cracked cauldrons --- all of these were thrown into a pile that soon towered over Altdorf's square on the very spot where Kilchmar had sealed his pledge three years before. Crowds cheered every new donation. One man lugged the stove that should have kept him warm that winter. God bless her, was the murmur when an old widow tossed in her jewelry. Tears flowed when the three best families gathered to contribute three golden coins. Ten oxcarts were needed to transport the metal to the village.

The villagers, though they had little metal of their own to offer, would not be outdone. As they minded the makeshift smelter for nine days and nights, they contributed whatever Schnapps remained in their fl asks at daybreak, plus a full set of wolf's teeth, a carved ibex horn, and a dusty chunk of quartz.

Twelve men were scarred for life with burns the day they poured the glowing soup into the molds. The first bell was as round as a fat turkey, the second, large enough to hide a small goat beneath it, and the third, the extraordinary third bell, was as high as a man and took sixteen horses to hoist into the belfry.

All of Uri gathered on the hill below the church to hear the bells ring for the first time. When all was set, the crowd turned their reverent eyes to Father Karl Victor Vonderach. He stared back at them as if they were merely a flock of sheep.

"A blessing, Father?" one woman whispered. "Would you bless our bells?"

He rubbed his temples and then stepped before the crowd. He bowed his head, and everyone else did the same. "Heavenly Father," he croaked through the spittle gathered in his throat. "Bless these bells that You have ---" He sniffed and looked around him, and then glanced down at his shoe, which rested in a moist cake of dung. "Damn them all," he muttered. He stalked back through the crowd. They watched his form until it vanished into his house, which had glass in its windows, but no slates yet on its roof.

Then the silent crowd turned to watch seven of Kilchmar's cousins march resolutely into the church— one to ring the smallest, two the middle, and four the largest bell. Many in the crowd held their breath as, in the belfry, the three great bells began to rock. And then the Loudest and Most Beautiful Bells Ever began to ring.

The mountain air shuddered. The pealing flooded the valley. It was as shrill as a rusty hinge and as rumbling as an avalanche and as piercing as a scream and as soothing as a mother's whisper. Every person cried out and fl inched and threw his hands over his ears. They stumbled back. Father Karl Victor's windows cracked. Teeth were clenched so hard they chipped. Ear drums burst. A cow, two goats, and one woman felt the sudden pangs of labor.

When the echoes from the distant peaks finally faded, there was silence. Every person stared at the church as if it might collapse. Then the door burst open and the Kilchmar cousins poured out, their palms held to their ruined ears. They faced the crowd like thieves caught with treasure in their stockings.

Then the cheering began. Hands rose toward heaven. Fists shook. Tears flowed. They had done it! The Loudest Bells Ever had been rung!

God's kingdom on earth was safe!

The crowd retreated slowly down the hill. When someone yelled, "Ring them again!" there was a collective cringe, and soon began a stampede— men, women, children, dogs, and cows ran, slid, rolled down the muddy hill and hid behind the decrepit houses as if trying to outrun an avalanche. Then there was silence. Several heads peered around the houses and toward the church. The Kilchmar cousins were nowhere to be found. Indeed, soon there was no one within two hundred paces of that church. There was no one brave enough to ring the bells again.

Or was there? Whispers filled the air. Children pointed at a brown smudge moving lightly up the hill, like a knot of hay, blown by a gentle wind. A person? No, not a person. A child --- a little girl --- in dirty rags.

It so happened that this village possessed, among its treasures, a deaf idiot girl. She was wont to stare down the villagers with a haunting glare, as though she knew the sins they fought to hide, and so they drove her off with buckets of dirty wash water whenever she came near. This deaf child was staring at the belfry as she climbed the hill, for she, too, had heard the bells, not in her vacant ears, but as we hear holiness: a vibration in the gut.

They all watched her climb, knowing that God had sent this idiot girl to them, just as God had sent them Kilchmar, had sent them the stone to build this church, and the metal to cast the bells.

She looked upward at the belfry as though she wished that she could fl y.

"Go," they whispered. "Go."

She does not hear them urge her on. But the memory of the bells' peal pulls her to the doors and into the church, where she has never been before. There are shards of glass on the floor --- the shattered windows— and so she leaves bloody footprints as she climbs the narrow stairs at the back of the church. On the first level of the bell tower, the three ropes hang through the ceiling. But she knows of ropes, and knows this magic is not from them, that they direct her farther up, and so she climbs the ladder and lifts the trap with her head. The sides of the belfry are open— there is no railing to stop a fall --- and she sees four different scenes: to the left, blank cliffs; in front, the valley winding upward toward Italy; to her right, the snowcovered Susten Pass; and when she climbs through the trapdoor, behind her, her audience gathered around the homes like maggots swarming rotting meat.

She walks beneath the largest bell and looks up into its shadows. Its body is black and rough. She reaches up and slaps it with her hand. It does not move. She does not feel a sound. There are two copper mallets leaning in the corner. She lifts one of them and swings it at the largest bell.

She feels it first in her belly, like the touch of a warm hand. It has been years since anyone has touched her. She closes her eyes and feels that touch radiate down into her thighs. It travels along the tracks of her ribs. She sighs. She hits the bell again with the mallet, as hard as she can, and the touch goes farther. It snakes around her back and up her shoulders. It seems to hold her up; she is floating in the sound.

Again and again she strikes the bell, and that sound grows warmer. She rings the middle bell. She hears it in her neck, in her arms, in the hollows behind her knees. The sound pulls at her, like warm hands are spreading her apart, and she is taller and broader in that little body than she has ever been before.

The small bell she hears in her jaw, in the flesh of her ears, in the arches of her feet. She swings the mallet again and again. She lifts the second mallet so she can use both arms to pound against the bells. In the village, at fi rst, they cheered and cried at the miracle. The echoes of pealing returned from across the valley. They closed their eyes and listened to their glory.

She rang the bells. A half hour passed. They could not hear each other speak. Some yelled to be heard; most just sat on logs or leaned against the houses and pressed their hands against their ears. The pigs had already been roasted. The casks of wine had been tapped, but how could they begin the feast of victory without a blessing?

"Stop it!" someone shouted.

"Quiet!"

"Enough!"

They shook their fists at the church.

"Someone has to stop her!"

At this demand, everyone looked shyly at his neighbor. No one stepped forward.

"Get her father!" they yelled. "This is a father's job!"

Old Iso Froben, the shepherd whose wife had given him this one, malformed child after twenty years of marriage, was pushed forward. He was not more than fifty, but his eyes were sunk, and his forearms, the fleshless stalks of a great- grandfather. He rubbed the back of his hand across his dripping nose and gazed up at the church as if he were being sent to slay a dragon. A woman came forward, stopped his ears with wool, and then wrapped dirty trousers around his head, tying them at the back like a turban.

He shouted something at the man next to him, who disappeared into the crowd and then, moments later, returned with a mule whip. So many times I would overhear the story: Brave Iso Froben struggled up the hill, one hand keeping the trousers from slipping over his eyes, the other on the whip. The steep path had been so muddied by thousands of eager feet that he slipped often, skidded two steps backward on his knees, clawed himself to his feet again. When he reached the church at last, he was covered from head to toe in mud. The whip sprinkled specks as it swung in his hand. Even with the wool in his ears and the trousers around his brow, the bells clenched and shook his head with each new ring.

The sound only grew louder as he entered the church and climbed the stairs, which seemed to shake beneath him. He held his palms over his stopped ears, but it did no good. He cursed God for the thousandth time for sending him this child.

At the first level of the belfry, he saw that the ropes were still, and yet the bells rang. He saw black spots before his eyes. As the world began to spin, he suddenly understood: These were not God's bells at all! They had been tricked. These were the devil's bells! They were all the devil's fools. They had built his church. They had cast his bells! He turned to run down the stairs, but then he glimpsed above him, in the cracks between the ceiling planks, the dancing of tiny, devilish feet.

There was courage left in that meager, withered frame. He clutched that whip as his sword. He climbed the ladder to the belfry and pushed open the trapdoor just far enough to peek.

She leapt. She twirled. She swayed and stretched. She swung the mallet and hung in the air as it impacted. The bells seemed to toll from within her, as if the bells she struck were her own black heart. She pranced along the edge, an invisible hand guiding her back to safety. She rang the largest bell: a sound like nails driven in his ears.

The plea sure glowing in her eyes was the last proof Iso Froben needed: his daughter was possessed by the dev il. He threw open the trapdoor and clambered through. The aged man was a warrior. He whipped the devil- child until she lay on the fl oor of the belfry without moving. Soon the bells' tolling was but a gentle ringing in the air. Cheers erupted from the village far below him. His daughter whimpered. He dropped his whip beside her and then descended. He passed through the celebrating town without pausing, and was never seen in Uri again, and so, after Kilchmar, he was the second, but not the final, victim of the bells.

Back in the church, only after dark did that child move. She lifted her head to make sure that her father was gone, and then sat up. Her clothes were bloody. The gashes in her back burned. Her dead ears were blank to the revelry in the village below. She took her mallets and opened the trapdoor.

Tomorrow, she thought as she looked up at the bells. Tomorrow I will ring you again.

The next day she did ring them, as she did the day after that, and every morning, noon, and night until her death.

This child was named Adelheid Froben, and I, Moses Froben, am her son.

Excerpted from THE BELLS © Copyright 2011 by Richard Harvell. Reprinted with permission by Broadway. All rights reserved.

The Bells

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Broadway

- ISBN-10: 0307590534

- ISBN-13: 9780307590534