Excerpt

Excerpt

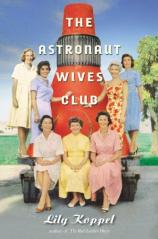

The Astronaut Wives Club

1

Introducing the Wives

They had endured years of waking up alone, making their kids breakfast, taking them to school and picking them up, fixing dinner and kissing them good night, promising that Daddy was thinking of them all the time. There had been lonely nights when they fell asleep wondering how they were going to get by on their husbands’ measly pay for another month. During tours of duty in World War II or Korea or both, their husbands had nearly become mirages. Navy deployments had taken their men away on six- to nine-month cruises to the far corners of the Earth. They’d each wait for half a year imagining their man, trying not to forget what he looked like, only to have him come home hungry and tired. They’d miss him even before he left.

Things were no easier in peacetime when he was back home on base serving as a test pilot. There were times when squadrons would lose as many as two men in a week. The wives couldn’t do a thing about it but pray for their prowess over the 5 a.m. skillet, hoping they’d cooked their husbands a good breakfast of steak and eggs before they left to go fly, so they’d be alert up in the air. They went to friends’ funerals, sang the Navy hymn, and wore white gloves and clutched a handkerchief to catch the tears. They’d become conditioned to living with the daily fear that their men might not be back for dinner, or ever.

For Marge Slayton, whose wide, pale Irish face and expressive eyes made you want to hug her, it was the sound of a helicopter that sent her into a tailspin of fear and nausea. Hearing the blades of a chopper whirring overhead almost always meant that the men were searching for a plane that had gone down. Long after she stopped living on remote air bases, such as Edwards in the Mojave Desert, the sound of a helicopter still struck fear in her heart.

If a husband was out testing a new experimental plane and didn’t come home by five o’clock, almost all of the wives experienced the same waking nightmare, imagining the dark figure of the base chaplain ringing the doorbell, telling her she was now a widow. They had rehearsed that awful scene in their minds, over and over. Such was the life of a test pilot wife. They could not possibly have imagined all that would be in store for them as astronauts’ wives.

The United States was well behind in the space race. Soon after launching Sputnik in 1957, the Russians launched Sputnik II with its passenger Laika (“Barker,” also known as Little Curly), the Soviet space dog. She was a female stray found on the streets of Moscow (and those godless Soviets let her die in orbit). The United States had responded by trying to send up its own satellite on a Vanguard rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida, but it disastrously exploded on the launch pad, leading the press to call it “Kaputnik.” In the following months and years the United States tried to send up bigger rockets, such as the Atlas, but nearly every one of them had exploded before reaching outer space. Now the United States was determined not only to catch up but to pull ahead. It was a national priority in those fervent days of the Cold War.

America’s space age was officially announced on April 9, 1959. In Washington, D.C., at the buttercup-yellow Dolley Madison House, across Lafayette Square from the White House, the seven men who’d been chosen to be the nation’s first astronauts were officially presented to the world. They sat onstage at a blue felt–draped banquet table under NASA’s round red- and-blue logo of a planet and stars, nicknamed the Meatball. Onstage with them was a model of the tiny Mercury capsule on top of an Atlas rocket, which would fall off once the capsule had passed through the Earth’s atmosphere and entered outer space. At promptly 10 a.m., the press conference began. T. Keith Glennan took the podium. A natural-born showman who had previously worked at Paramount and Samuel Goldwyn, he was now the administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he announced, “today we are introducing to you and to the world these seven men who have been selected to begin training for orbital spaceflight. These men, the nation’s Mercury astronauts, are here after a long and perhaps unprecedented series of evaluations which told our medical consultants and scientists of their superb adaptability to their upcoming flight. It is my pleasure to introduce to you—and I consider it a very real honor, gentlemen—Malcolm S. Carpenter, Leroy G. Cooper, John H. Glenn Jr., Virgil I. Grissom, Walter M. Schirra Jr., Alan B. Shepard Jr., and Donald K. Slayton . . . the nation’s Mercury astronauts!”

The ballroom burst into applause. The Mercury Seven astronauts were instantly beloved, embodying the country’s optimism and excitement. Space capsules and rocket launchers and men in silver suits in outer space; it was a brave new world. The stuff of science-fiction novels was now coming true. These seven young flyboy test pilots, with their strong jaws and military buzz-cuts, were the best America had to offer. Glennan explained how the seven were chosen out of 110 test pilots considered for the job. Most of all they were healthy small-town Americans. None was older than forty.

Glennan touched on how fierce the competition had been. The Mercury Seven had been exhaustively tested and checked out down to their innermost orifices at the famed Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque, selected for its secluded location. There were all kinds of “wild theories” about zero gravity, as one NASA doctor later put it. “Some people said the astronauts’ hearts would explode, or that their blood pressure would fall to nothing. Some said they would never be able to urinate, and others said they’d never be able to stop urinating.” Physicians did a complete medical, psychological, and social evaluation of the astronauts. NASA looked into the backgrounds of not only the men but also their wives.

Since all of America’s new astronauts were drawn from the test pilot world, they were military men who would retain their rank while on loan to the new civilian space agency. They would work together now, so rank would no longer be important. They wouldn’t wear uniforms besides their silver space suits. And they wouldn’t only be pilots. Each would be in charge of a particular ingredient of spaceflight, such as the capsule, communications, recovery, or navigation.

When it was question time, the reporters shot up their hands and leaped out of their seats. It turned out they were mostly interested in what the astronauts’ wives had to say about their men being blasted into space. It was insanity, wasn’t it? Or was it the American dream? Didn’t their wives want to bring the country down to earth, say there had been some mistake? No, you cannot send my husband to the Moon. What kind of woman would actually let her husband be blasted into space on a rocket? The newly christened astronauts were in the process of formulating answers when John Glenn piped up.

“I don’t think any of us could really go on with something like this if we didn’t have pretty good backing at home, really,” he said, speaking of his Annie. “My wife’s attitude toward this has been the same as it has been all along through my flying. If it is what I want to do, she is behind it, and the kids are, too, a hundred percent.”

When the press conference ended, reporters dashed from the room to instruct their editors to dispatch their minions to track down the Astrowives. John Glenn, who would remain very protective of his wife throughout the space race, always did his best to shield her from the press. The other wives, however, were open game. There were seven of them scattered across the country: Air Force and Navy wives, and Annie the lone Marine wife. They had spent the best years of their lives raising kids and supporting their husbands’ careers and moving their families from one end of the country to the other, from one dismal base to the next. Now their husbands were astronauts, and they, too, were instant celebrities.

NASA didn’t provide the wives with any instructions. No NASA public relations spokesmen contacted them with tips on how to deal with the press that day. The wives would have to handle the reporters the way they’d handled all the ups and downs of service life—with slightly knitted eyebrows, perfectly applied lipstick, and well-practiced aplomb.

The reporters hunted down the wives, showing up at their doorsteps and even chasing them at the grocery store. Out in Enon, Ohio, Betty, new astronaut Gus Grissom’s wife, was having a hellish time dealing with the journalists, who were practically crawling through the curtains into her house. Gus had vastly underestimated the new situation the night before, when he’d called from Washington to warn her, “It’s a good bet you’ll be pounced on by the press.” She’d been sick, running a temperature of 102. Her curly brown hair was a mess. So was the house.

Betty Grissom had never thought of Gus as a potential hero. They’d met back in Mitchell, Indiana, where Gus, too short to make the basketball team, had to be satisfied with being the leader of the Boy Scout honor guard. Betty played the snare drum in the pep band. “The first time I saw you I decided you were the girl I was going to marry,” he’d tell her.

Betty had put Gus through engineering school at Purdue, slaving away on the 5 to 11 p.m. shift at Indiana Bell in a room full of exhausted working girls plugging in telephone connections. Her graveyard shift gave her husband some quiet to study. She had to work hard in those days because they lived off her pay. Betty didn’t have any education beyond high school, but she often joked about her hard-earned “P.H.T.” degree—Putting Hubby Through.

She had sweated out Gus’s tour of duty in Korea, where he flew an F-86 Sabre on one hundred combat missions. Gus was promoted, but Betty was devastated when he actually volunteered to stay in Korea to fly another twenty-five missions.

After the war, Gus was stationed at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. He was now a test pilot, and they were finally living under one roof, with their two little boys. Even though Gus was home, he was often off flying. Betty knew flying was Gus’s life, and she supported him without question.

“If I die, have a party,” Gus once told her after one of their test pilot friends crashed and burned.

“Okay,” she promised. “We’ll have a party.”

“If something happens to me, I don’t want people sitting over here, crying.”

In January 1959 Gus had received the top-secret telegram. Gus wasn’t much for words, but Betty usually knew before he did what was on his mind. In fact, they both figured that she was a little psychic. That night, as the Moon hung over Enon, Ohio, and the two boys were finally in bed, he read the telegram aloud. A couple of sentences long, with the usual confusing military acronyms, it “invited” Captain Virgil I. Grissom to come to Washington, wear civilian clothes, and not utter a word of this to anyone. Neither of them had any idea what it meant, so Betty blurted out the craziest thing that popped into her head. “What are they going to do, Gus, shoot you up in the nose cone of an Atlas rocket?”

She had heard Gus talk about the Atlas rocket, which was being tested in secret at Cape Canaveral in Florida. It wasn’t much of a secret, seeing as reporters had watched it blow up from the nearby town of Cocoa Beach. The rocket was unstable, and kept on exploding at liftoff after liftoff. Did men in the government really reckon someone was supposed to ride that thing?

Gus laughed. Soon Betty began to feel like a spy girl in a James Bond thriller. Federal investigators were canvassing Enon, making inquiries into the character of the Grissoms: How patriotic was his wife? How many times a week did she make home-cooked meals? Did she drink too much? Did communists regularly appear on their doorstep?

Finally, Gus asked Betty’s permission to accept the dangerous mission. She looked at him and said, “Is it something you really want to do?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Then do you even need to ask me?”

On the day of the astronauts’ press conference, Betty had gone to the doctor and gotten a shot of penicillin. She stopped at the grocery store on the way home to pick up a few things for her and her boys, eight-year-old Scotty and five-year-old Mark, who were still at school. A reporter-photographer team from Life had interviewed her neighbor and tracked Betty’s trail to the store. They came right up to her as she was wheeling her shopping cart through the vegetable aisle. Being a polite midwesterner, Betty invited the duo to her home, though they would have followed her through her door whether she wanted them to or not.

As soon as she let the Life fellows in, other reporters and photographers started arriving. They didn’t even knock, just marched right in her front door and made themselves at home. Asked all sorts of personal questions, Betty didn’t view these invasions as a welcome opportunity to become famous.

Sitting off to the side in her living room, as if the men wanted to photograph her dingy furniture and not her, Betty slung one saddle-shoed foot over the other, hoisted up her bobby socks, and watched suspiciously. Her big round owl glasses almost hid how cute she was. A perpetual worrier, she noted every time one of the men used the toilet (which she scrubbed herself) or plugged heavy equipment into a socket without permission. She didn’t like the reporters: she hadn’t prepared for this at all.

Betty didn’t mind putting up with a lot for Gus. But she expected some common decency.

On the other side of the country, on a windswept shore near her home in Virginia Beach, Louise Shepard had taken her three lovely girls to the beach to escape the reporters who would surely be ringing her bell at home. Louise walked slowly up the shore-line as her blonde-haired girls built sandcastles and waded in the surf.

“Mrs. Shepard?” The press had tracked her down. “We’re from Life magazine, Mrs. Shepard. We’d like to take some pictures.”

Louise had always played a supporting role to her husband, Alan. She was a Christian Scientist and did not like this invasion of her quiet life, but assumed her new role was beginning, and she handled the press gracefully. She smiled tentatively at the two men from Life and told them it would be okay if they took a few pictures. She smoothed out the girls’ windblown hair and posed for the photographer.

After Louise let them instruct her to look left and look right, look up toward the sky, where her husband’s bird might one day go, she was ready to get out of there. She looked at them kindly, smiled a smile that meant, That’s enough, then put two slender fingers in her mouth and whistled. “Laura, time to go.”

The men were flummoxed. Louise rounded up her girls. They thought the attention was fun, but they followed their mom to the car. Louise calmly steered toward home, expecting that by now, any press that had come calling would be gone.

She was wrong. When she turned onto her quiet street, lined with wooden houses with pleasant gardens hemmed in by picket fences, she could hardly believe her eyes. There must have been a dozen news trucks in her yard.

“How does it feel being the wife of an astronaut?” The men started flinging questions right away. “How long have you been married? What do your kids think?”

Louise stared into the exploding flashbulbs.

“Do you really want him to go?” asked another newsman. “Aren’t you worried he’ll be killed?”

That was the question that really disturbed her. Louise had been living with the fear of Alan’s death ever since he started test-flying high-performance jets. The death rate for men like Alan was staggering. If Alan didn’t call or come home by five o’clock sharp, Louise would start looking at the sky for the ominous black clouds near an air base that rose from a plane crashing to the ground.

Finally, she enveloped her children in her arms and ushered them through the crowd, away from all the attention. Down the street, the neighbors were watching the drama unfold in the Shepards’ yard, and a mother told her son to be a dear and go see what all the hoopla was about. He ran back home and announced, “Mom! Mom! You gotta hear this! Mr. Shepard’s going to the Moon!”

* * *

Rene Carpenter’s husband, Scott, had called from Washington, D.C., the night before to tell her that the press was likely going to be coming this morning. Rene dressed in a classic sheath and planned to outfit her two toddler-age girls in matching red dresses piped in gold and black rickrack.

As the sun rose over the Carpenters’ house on Timmy Lane in Garden Grove, California, the reporters started arriving. Soon one of them was knocking on the front door.

“Mrs. Carpenter?” the reporter asked. “Yes?”

“We know you can’t talk to us till seven a.m. But do you mind if we set up a few things in the yard?”

“Yes, please do.”

The thirty-year-old mother of four had a welcoming smile, green eyes, platinum hair, and deep dimples. She was a winning combination of beauty and bookishness. In high school, she had wanted to be an actress and a writer. At the University of Colorado, the intellectual Tri Delta sorority girl had been writing a paper on Paradise Lost when she’d met Scott during her shift at the Boulder Bookstore. He showed up one afternoon after spotting her for the first time at the Boulder Theater, where she also worked, as a movie usherette. After they discovered they both loved to ski and discuss literature and philosophy, they decided to build a life together and got married. She helped support them, continuing to work at the bookstore as Scott made his way toward his degree. Before graduating, he joined the Navy.

Soon the reporters were again at the door, asking if they might come in to take some photos. She knew how to be a gracious hostess, having been a Navy wife for a decade now. As

Rene invited them in, the reporters took note of how she pronounced her name; it rhymed with keen. She let the reporters tour her home, filled with cherished family items like the teardrop-shaped monkeypod coffee table. Rene had picked up the raw wood for it when they were stationed in Hawaii. She had fashioned it into a base for the coffee table herself. One of the few perks of being married to an aviator was that the Navy would move your furniture for free, as you uprooted yourself from one base to the next.

Rene offered the newsmen coffee to go with the donuts some of the more enterprising of them had brought. They rearranged the furniture to make way for the lights and cameras now unblinkingly trained on her family.

Sitting on her orange couch with her gang of four, Rene posed for more photos. Nine-year-old Scotty Jr. had donned his dad’s flight helmet, dark visor down, breathing into its ventilator tube hanging from the snout. He made quite a subject for the photographers.

Rene was as excited about this bold new endeavor as the news-men. “We all want to go with him!” she told them. “Even the two dogs!”

Finally the reporters packed up and left. “It’s as if I’d been acting on a dark stage all my life,” Rene said later. “And suddenly someone turns on the spotlight.”

Marge Slayton welcomed the press boys with her silent-film-star smile. She and Deke were stationed at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave, where Joshua trees rose like gnarled arthritic hands out of the lakebed runway. She had been gung ho ever since the space race began on an October night in 1957 when Russia launched Sputnik over the United States on the same evening Leave It to Beaver made its television debut. Sputnik means “fellow traveler” in Russian.

As the 1950s had progressed, the threat of nuclear war became more and more real. In schools, children practiced “duck and cover” drills, crouching under their desks and covering their heads with their arms. Fallout shelters abounded in towns and cities. Some families constructed their own bomb shelters in basements or backyards, stocking them with survival kits complete with bottled water, evaporated milk, and enough canned goods to last through the nuclear winter. As the Americans and Russians continued to build up their arsenals, the country lived in fear of thermonuclear war. It was a devil’s bargain to keep the peace known as MAD, or mutually assured destruction.

On the night of October 4, 1957, terror in their hearts, men, women, and children ran outside to search the nighttime sky for the Russian interloper, masterminded by the shadowy Soviet chief designer. The unmanned aluminum satellite orbiting the Earth looked like a spiky silver bug. What might the Soviets do next? America had nightmares of future Sputniks dropping atom bombs onto their happy homes. Nobody wanted to live under a communist Moon. Texas senator Lyndon B. Johnson feared precisely that, saying, “I’ll be damned if I sleep by the light of a Red Moon . . . soon they will be dropping bombs on us from space like kids dropping rocks on the cars from freeway overpasses.” The next morning, the front pages of newspapers across the country bore images that looked like the old Martian-infested EC Comics, predecessor to Mad magazine. Nikita Khrushchev bragged that the U.S.S.R. could mass-produce rockets like “sausages.” Important officials called the launch of Sputnik “a technological Pearl Harbor.”

A few nights after Sputnik, Marge and the other wives at Edwards Air Force Base got an idea to give their men a much-needed laugh. They dressed up like Playboy Bunnies in sexy black seamed stockings, black bathing suits, and little skirts. When their guys gathered at a lonely supper club out there in the middle of nowhere, the women came out dancing in a chorus line. They had affixed miniature Sputniks on top of their caps, which whirled along with the dance. Marge’s husband, Deke, whistled as the girls shook their Sputniks. Come and get me, beckoned Marge and her Sputnik sweetheart revue. At one point, the gals turned around and flipped up their skirts and shook their fannies. When assembled, the secret message could be deciphered. Written in white lettering across their black bloomers were the words TAKE ME TO YOUR LEADER.

“Of course, I’m pleased my husband was selected as an astronaut. It’s a great honor. Do I have any fears about the unknowns of spaceflight? Do you know of anyone who’s going to be boosted out of this world who wouldn’t be apprehensive?”

The reporters’ questions brought Marge back to reality.

“Yes, I’m familiar with the dangers. Yes, I’ve lived with them for years through Deke’s service as a fighter pilot and a test pilot,” she said. “Yes, I stand by him. Yes, I support Deke all the way. No, I have no reservations about what he has chosen to do.”

Marge told the reporters how she had met Deke in Germany after World War II, where he was a bomber pilot and she was a secretary for the civil service. They met at a volleyball game on base. Marge hit a spike and broke her wrist. She described for the newsmen how tough-looking Deke carried her to the base hospital, her very own Prince Charming. Marge couldn’t help but be reminded of her Irish father, a rough-and-tumble detective for the railroads. He drank too much and was often violent. Deke was much, much kinder. They both thought there was something a bit odd about the doctor who set Marge’s wrist, but just figured he was a kook. A couple of weeks later, the doctor was found in his room, painted up with iodine like an Indian and shooting holes in the ceiling with a Colt .45. Another doctor had to break Marge’s wrist again and reset it, and throughout the whole awful process, Deke was with her every day, so gentle. They soon bought a velvety gray Weimaraner puppy together and named him Acey. Seeing Deke pet the pint-sized Acey simply made Marge melt.

Deke was so different from her previous husband, but Marge didn’t want anyone—especially at NASA—to know she had been divorced. Divorce was taboo at the space agency, which believed that stable home lives were essential for success in orbit. One of the first among NASA’s many unofficial rules was: if you don’t have a happy marriage, you won’t have a spaceflight.

Suddenly the phone rang. It was Deke calling from Washington after the press conference.

“Hi, honey.”

Marge pressed the receiver of the black phone to her cheek while she surveyed her quarters. Her two-year-old son, Kent, was fighting the photographers like a diapered Don Quixote. All at once, her whole world had changed. Marge brought Kent close to her, holding him out of harm’s way.

The photographers took a shine to little Kent. On one occasion, Life got him to ride Acey, who, now full grown, weighed ninety-eight pounds and towered over Kent. They took a photo of the astronaut’s son riding the dog like a nursery pony. Unfortunately, Acey was a maniac, and every time Kent tried to pet him, the dog tried to bite him.

Trudy Cooper and her husband, Gordo, were also stationed at Edwards. Any wife would be happy to leave this place where sandstorms blew through the cracks and crevices, turning base housing into a veritable hourglass, with sands pouring down through the light fixtures onto freshly set dinner tables.

One of the first household tips the Edwards wives passed down was “Don’t move a thing.” The sand problem was so bad that if you moved anything—a book, lamp, paperweight—it left a shadow ringed with a fine layer of dust. If you liked rearranging things, you’d be dusting until kingdom come. Another piece of advice was to watch out for the snakes; there were all kinds of poisonous ones, including Mojave greens and sidewinder rattlers.

An enigmatic woman who was always conspicuously quiet with reporters, Trudy relied on her kittenish eyes to say, I’m happily married. It was all that anyone seemed to be able to get out of her.

Trudy’s husband, Gordo, was a tanned, cocky little fellow with a wide country boy’s grin. He was the youngest of the astronauts, and the most experienced pilot in the group. He was real slow-talkin’ and from Oklahoma. When chestnut-haired Trudy met Gordo at the University of Hawaii, she was already a pilot herself, dashing in Wayfarers as she purred over Oahu Island in a Piper Cub. Her heart was set on entering the Powder Puff Derby, the women’s transcontinental air race founded decades earlier by Amelia Earhart and Pancho Barnes. Pancho had once run Pancho’s Happy Bottom Riding Club, a bar on Edwards Air Force Base, and led a gang of hellcat aviatrixes in Pancho Barnes’s Mystery Circus of the Air. Gordo was used to adventurous women. Hell, his eighty-six-year-old grandmother, still kicking in Shawnee, Oklahoma, was a rootin’-tootin’ cowgirl who said she’d go with Gordo into space if she could.

The reporters pressed on. It was amazing how an adventurous gal like Trudy—the only licensed pilot among the new astronaut wives—was so damn quiet. Well, maybe she’d adopted some of the stoicism of her male counterparts. Compared to some of the chattier wives, her silences were almost rude, frankly. The truth was, Trudy didn’t want anyone to find out her dirty little secret. Gordo had gotten up to more mischief than she could handle at Edwards.

Before the astronaut selection process had begun four months before in January 1959, Trudy had left Gordo after twelve years of marriage. (“Because he was screwing another man’s wife out there in California,” one of the astronaut wives would later reveal in a loud whisper.) She gathered her two daughters, Camala Keoki and Janita Lee (she and Gordo had named them with a Hawaiian nostalgia), and took off to San Diego, ready to start a new life for herself and her girls, sans Gordo. After years of supporting Gordo’s career only to find him cheating on her, she now had the chance to pursue her own dreams.

Then one day, Gordo came banging on her door wanting her to come out and talk. With his aw-shucks demeanor, Gordo could somehow manage to look both dejected and excited. He was pretty sure he’d aced the extensive testing NASA had put him through. (Sperm counts, electrical stimulations, five barium enemas? Good God.) He’d been thoroughly checked out, stamped, and approved as grade-A American beefcake. He scored big on all the psychological tests at Wright-Patt, and the headshrinkers concluded that Gordo was just like any other supernormal fellow with a healthy male appetite.

Gordo always talked slowly, even if his wheels were spinning. It was the chance of a lifetime—he’d be shot up on an Atlas rocket into space! He was about to be an astronaut; all that was left for him to succeed was to produce a loving wife. A good marriage would ensure his appointment. After all, how could an astronaut handle the pressures of getting shot into the heavens if he couldn’t even handle his wife on Earth? (Not to mention that if Trudy stuck around, she’d prob’ly reap plenty of goodies and rewards herself.)

At the very least, the flying part was enough to excite Trudy. Gordo was the best pilot Trudy had ever seen, and she was a good judge, being a damn good pilot herself. If anyone was going to outfly those Russians, it was Gordo.

Honey,Gordo’s smile seemed to say, think about the girls, think about Cam and Jan. I don’t want to leave them behind when I’m a famous as hell astronaut. Gordo had a way of making Trudy feel like she was not quite up to the challenge. He’d go around behind her back calling her a prude because she was very proper, the top button always done up on her tailored shirt. So what if she didn’t like to get undressed in front of other women in the locker room of the Officers Club on base? Perhaps it was the competitive pilot in Trudy, but she couldn’t bear to let such a choice assignment be forfeited. She’d go along with him. And she’d have to get over that stoic demeanor because talks were already under way to give Life magazine exclusive coverage of the astronauts’ and their wives’ “personal stories.” They would do a major story on the seven astronauts together, then on their seven wives. Separate stories on each family would be published over the course of Project Mercury. The reward would be big—$500,000.

If there was anything more amazing that Gordo could have told Trudy, she didn’t know what it was. Like all of America’s new astronaut wives, Trudy had become adept at stretching Gordo’s military pay of around $7,000 a year. The idea of half a million dollars, which was to be divvied up equally among the seven new space families (that meant over $70,000 each), was like winning the lottery. You could only laugh at that number.

Turning a blind eye to Gordo’s affair, Trudy decided to go along with him on his space adventure. She let Gordo drag her back to godforsaken Edwards. Just like that, Trudy and Gordo and little ten-year-old Cam and nine-year-old Jan were back together living the American dream. She’d fooled NASA easily.

Stork-like blonde Jo Schirra sat on her couch in her quarters at the Naval Air Test Center at Patuxent River in Maryland, otherwise known as Pax River, where her husband, Wally, was a Navy test pilot.

Jo was Navy royalty. Her stepfather, four-star admiral James L. Holloway Jr., known as Lord Jim, had been appointed by President Eisenhower to be in charge of all United States naval forces in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean. She knew very well the proper codes of behavior, taught to her by her Navy-wife mother, Mrs. Admiral Holloway—how to dress, how to serve tea to an officer, how never to go to an official function without her white gloves, pearls on, and calling cards. And how to always say the right thing. If Jo had any questions about the customs of the service and the management of a shipshape Navy household, she could always turn to The Navy Wife, the bible for any service wife, written by two inimitable Navy wives, Anne Briscoe Pye and Nancy Shea. Throughout her husband’s early officer’s career, Jo followed “the rules” to the letter.

Before she was a Navy bride, she was a Navy brat who’d spent her teenage years in Shanghai with a rickshaw running her and her sister through the city streets on their way to the American Officers Club. When she first married Wally and they were stationed in China, where he was a naval attaché, Jo felt as if she were going home. As a young bride, she had her very own amah, the lady who drew her bath and laid out her clothes on her bed canopied in mosquito netting. The more exotic something was, the more Jo loved it. And space was very exotic.

John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Alan Shepard, Scott Carpenter, Deke Slayton, Gordon Cooper, and Wally Schirra were about to report for duty at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia, NASA’s headquarters for Project Mercury. Training would start there in the late spring of 1959. As Vice President Richard Nixon declared in the so-called Kitchen Debate that summer with Khrushchev, the Russians might be ahead in rocketry, but America was ahead in the accoutrements of middle-class life. The wives were prime examples, helpmates in complete operational control of kitchens chock-full of nifty new gadgets— dishwashers, Frigidaires, electric can openers, and Westinghouse electric ranges. None of the seven astronaut wives knew exactly what lay ahead for them, but they believed they were living on the winning side of the Cold War.

The Astronaut Wives Club

- Genres: History, Nonfiction

- hardcover: 288 pages

- Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-10: 1455503258

- ISBN-13: 9781455503254