Excerpt

Excerpt

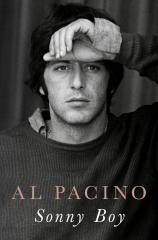

Sonny Boy: A Memoir

1

A Blade of Grass

I was performing since I was just a little boy. My mother used to take me to the movies when I was as young as three or four. She did menial work and factory jobs during the day, and when she came home, the only company she had was her son. So she'd bring me with her to the movies. She didn't know that she was supplying me with a future. I was immediately attached to watching actors on the screen. Since I never had playmates in our apartment and we didn't have television yet, I would have nothing but time to think about the movie I had last seen. I'd go through the characters in my head, and I would bring them to life, one by one, in the apartment. I learned at an early age to make friends with my imagination. Sometimes being content in your solitude can be a mixed blessing, especially to other people you share your life with, but it usually beats the alternative.

The movies were a place where my mother could hide in the dark and not have to share her Sonny Boy with anyone else. That was her nickname for me, the one she gave me first, before everyone else started calling me Sonny too. It was something she picked up from the movies, where she heard Al Jolson sing it in a song that became very popular. It went like this: Climb up on my knee, Sonny Boy

Though you're only three, Sonny Boy

You've no way of knowing

There's no way of showing

What you mean to me, Sonny Boy

It stuck in her head for a dozen years, and at my birth in 1940, the song was still so vivid to my mother that she would sing it to me. I was my parents' first child, my grandparents' first grandchild. They made a big fuss over me.

My father was all of eighteen when I was born, and my mother was just a few years older. Suffice it to say that they were young, even for the time. I probably hadn't even turned two years old when they split up. The first couple of years of my life my mother and I spent constantly moving around, no stability and no certainty. We lived together in furnished rooms in Harlem and then moved into her parents' apartment in the South Bronx. We hardly got any support from my father. Eventually, we were allotted five dollars a month by a court, which was just enough to cover our room and board at her parents' place.

Many years later, when I was fourteen, my mother took my father to court again to plead for more money, which he said he didn't have and which we didn't get. I thought the judge was very unfair to my mom. It would take decades for the courts to have some sense about a single mother's needs.

To find the earliest memory I have of being together with both of my parents, I have to go back to when I'm about three or four years old. I'm watching some movie with my mother in the balcony of the Dover Theatre. The story is some sort of melodrama for adults, and my mother is totally transfixed. I know I am watching something that's really meant for grown-ups, and I imagine there is a certain thrill in that, in being a little kid at my mother's side and sharing this time with her. But I can't quite follow the plot, and my attention wanders. I look down from the balcony, into the rows of seats below us. And I see a man walking around there, looking for something. He is wearing the dress uniform of an MP-the military police, which my father served in during World War II.

He must have seemed familiar, because I instinctively shouted out "Dada!" My mother shushed me. I didn't understand why. How could you say shush? I shouted for him again. "Dada!" She kept whispering "Shh-quiet!" because he was looking for my mother. They were having problems, and she didn't want him to find her, but now she had been found.

When the film was over, I remember walking on the dark street at night with my mother and father, the marquee of the Dover Theatre receding behind us. Each parent held one of my hands as I walked between them. Out of my right eye I saw a holster on my father's waist with a huge gun pouring out of it, with a pearl-white handle. Years later, when I played a cop in the film Heat, my character carried a gun with a handle like that. Even as a little child, I could understand: That's powerful. That's dangerous. And then my father was gone. He went off to the war and came back, but not to us.

Later in life, when I was acting in my first Broadway show, my relatives from my father's side of the family came to see me. I was this young, avant-garde actor who had spent most of his time in Greenwich Village and gradually worked his way onto Broadway. After the show, a couple of my aunts and a kid or two of theirs paid me a surprise visit in the hallway backstage. They started showering me with kisses, hugging me and congratulating me. They were Pacinos, and though I knew them from making the occasional visit to my grandmother on my father's side, I was somewhat bashful.

But as we made small talk, something came up in conversation that struck me to the bone. They said something about "the time that you were with us." I said, "What do you mean, when I was with you?" They said, "When you were with us, remember? Oh yeah, Sonny Boy, when you were hardly more than a baby, not quite a year and a half old, you lived with your grandma and grandpa-your daddy's mother and father."

I said, "How long did I live there?"

About eight months, they said, nearly a year.

And suddenly things started to come together in my head. I was taken away from my mother for eight months while my father was away in the war. But I wasn't sent to an orphanage or put in a foster home; I was mercifully given over to a blood relative-my father's mother, my grandmother, who was an absolute gift from God. I have had lifesavers throughout my time on this planet, and she was perhaps the first.

This realization knocked me over. I had a sudden clarity about the inexplicable things I had done in my life this far, at twenty-eight years old-the checkered way I lived, the choices I made, and the ways I dealt with things. It was a revelation to learn that I had been given away, at least temporarily, at the age of sixteen months. To have been totally dependent on my mother, knowing nothing else, and then sent off to a whole different life-that's a powerful rupture. Shortly after that, I went into therapy. I certainly had things that needed to be dealt with.

My dad's mother was Josephine, and she was probably the most wonderful person I've ever known in my life. She was a goddess. She just had this angelic countenance. She was the kind of woman who, in the old days, would go down to Ellis Island and wait for the new arrivals, Italians and anyone else who didn't know English, so she could help them. She cared and fought for me so much that she was given visitation rights to me in my parents' divorce settlement. Her husband, my grandfather and namesake, Alfred Pacino, arrived in New York from Italy in the early 1900s. They had an arranged marriage, and my grandfather worked as a house painter. He was a drunk, which made him moody and unpredictable.

I have no memory of that time I spent in their household, away from my mother. I imagine my mother had guilty feelings about the arrangement. She must have. Sure, I wasn't separated from my mother for a very long time, but at that young age, eight months was long enough.

When my son Anton was a little boy, not yet two years old, I can remember a time when we were together on Seventy-Ninth Street and Broadway and his mother wasn't there. He had a look on his face like he was completely lost. I thought to myself, It's because he doesn't know where his mother is. He was actually looking for her-looking past other people on the street to see if he could find her. He was close to the age I was when I lived with my father's parents. I never saw my son so lost at sea, before or since. I picked him up and told him, "Mama is coming, don't worry." That's what he needed to hear.

My mother's parents lived in a six-story tenement on Bryant Avenue in the South Bronx, in an apartment on the top floor, where the rents were cheapest. It was a hive of constant activity, with just three rooms, all of which were used as bedrooms. These were small rooms, but not small to me. Sometimes we would have as many as six or seven of us living there at a time. We lived in shifts. Nobody had a room all to themselves, and for long stretches of time, I slept between my grandparents. Other times, when I slept in a daybed in what was supposed to be the living room, I never knew who might end up camped out next to me-a relative passing through town, or my mother's brother, back from his own stint in the war. He had been in the Pacific, and like so many other men who had seen combat, he wouldn't talk about his experience in the war. He would take wooden matchsticks and put them in his ears to drown out the explosions he couldn't stop hearing.

My mother's father was born Vincenzo Giovanni Gerardi, and he came from an old Sicilian town whose name, I would later learn, was Corleone. When he was four years old, he came over to America, possibly illegally, where he became James Gerard. By then he had already lost his mother; his father, who was a bit of a dictator, had gotten remarried and moved with his children and new wife to Harlem. My grandfather had a wild, Dickensian upbringing, but to me he was the first real father figure I had.

When I was six, I came home from my first day of school and found my grandfather shaving in our bathroom. He was in front of the mirror, in his BVD shirt with his suspenders down at his sides. I was standing in the open bathroom doorway. I wanted to share a story with him.

"Granddad, this kid in school did a very bad thing. So I went and told the teacher and she punished that kid."

Without missing a stroke as he continued to shave, my grandfather said to me simply, "So you're a rat, huh?" It was a casual observation, as if he were saying, "You like the piano? I didn't know that." But his words hit me right in the solar plexus. I could feel myself slinking down the sides of the bathroom doorway. I was crestfallen. I couldn't breathe. That's all he said. And I never ratted on anybody in my life again. Although right now as I write this, I'm ratting on myself.

His wife, Kate, was my granny. She had blond hair and blue eyes like Mae West, a kind of rarity among Italians, which sort of set her apart from all my relatives. She may have had some German blood on her side. When I was around age two, I guess, she would sit me on her kitchen table and spoon-feed baby food to me as she told extravagant, made-up stories in which I was the main character. That had to have made an impact. When I got a little older, I would find her cooking in the kitchen, peeling potatoes, and I would eat them raw. They had little nutritional value, but I loved the way they tasted. Sometimes she gave me dog biscuits and I ate those too.

My grandmother was known for her kitchen. She made Italian food, of course, but we weren't in an Italian neighborhood. As a matter of fact, we were the only Italians living in our neighborhood. Perhaps there was one across the street, a guy named Dominic, a jolly kid, who had a harelip. When I'd be going out the door, grandma would stop me right in my tracks with her wet cloth, which always seemed to be in one of her hands, to say, "Wipe the gravy off your face. People will think you're Italian." There was a kind of stigma against Italians when we first started coming over to America, and it only escalated when World War II started. America had just spent four years fighting against Italy, and though many Italian Americans had gone overseas to battle their own brethren and help bring down Mussolini, others were labeled enemy aliens and put in internment camps. When Italian Americans came back from the war, they intermarried with other groups at sky-high rates.

The other families in our tenement were from all over Eastern Europe and other parts of the world. You heard a cacophony of dialects. You heard everyone. Our little stretch between Longfellow Avenue and Bryant Avenue, from 171st Street up to 174th Street, was a mixture of nationalities and ethnicities. In the summertime, when we went on the roof of our tenement to cool off because there was no air conditioning, you'd hear the murmur of different languages in a variety of accents. It was a glorious time: a lot of poor people from various ghettos had moved in, and we were making something out of the Bronx. The farther north you went, the more prosperous the families were. We were not prosperous. We were getting by. My grandfather was a plasterer who had to work every day. In those days, plasterers were highly sought after. He had developed an expertise and was appreciated for what he did. He built a wall in the alleyway for our landlord, who loved the wall he built so much that he kept our family's rent at $38.80 a month for as long as we lived there.

Until I was a little older, I wasn't allowed out of the tenement by myself-we lived in the back, and the neighborhood was somewhat unsafe-and I had no siblings. We had no TV and not much in the way of entertainment, aside from a few Al Jolson records that I used to mime along to for my family's enjoyment when I was three or four. My only companions, aside from my grandparents, my mother, and a little dog named Trixie, were the characters I brought to life from those movies my mother took me to. I had to have been the only five-year-old who was brought to The Lost Weekend. I was quite taken with Ray Milland's performance as a self-destructive alcoholic, which won him an Oscar. When he is struggling to get dry and suffering from the d.t.'s, he hallucinates the sight of a bat swooping from a corner of his hospital room and attacking a mouse going up the wall. Milland could make you believe he was caught in the terror of this delusion. I couldn't forget the scene when he's sober, searching frantically for the booze that he squirreled away when he was drunk but can't remember where he hid it. I would try to perform it myself, pretending to ransack an invisible apartment as I scavenged through unseen cabinets, drawers, and hampers. I got so good at this little routine that I would do it on request for my relatives. They would roar with laughter. I guess it struck them as funny to see a five-year-old pretending to scramble through an imaginary kitchen with a kind of life-or-death intensity. That was an energy within myself that I was already discovering I could channel. Even at five years old, I would think, what are they laughing at? This man is fighting for his life.

Excerpted from SONNY BOY by Al Pacino. Copyright © 2024 by Al Pacino. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Sonny Boy: A Memoir

- Genres: Memoir, Nonfiction

- hardcover: 384 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Press

- ISBN-10: 0593655117

- ISBN-13: 9780593655115